Lisbeth Salander

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Swedish. (July 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

| Lisbeth Salander | |

|---|---|

| Millennium character | |

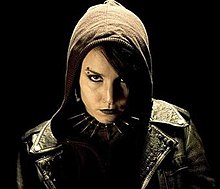

Lisbeth Salander, as portrayed by Noomi Rapace in the Swedish film | |

| First appearance | The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005) |

| Last appearance | The Girl Who Lived Twice (2019) |

| Created by | Stieg Larsson |

| Portrayed by |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Wasp, Irene Nesser, Monica Sholes |

| Gender | Female |

| Occupation |

|

| Family |

|

| Nationality | Swedish with Russian ancestry |

Lisbeth Salander is a fictional character created by Swedish author and journalist Stieg Larsson. She is the lead character in Larsson's award-winning Millennium series, along with the journalist Mikael Blomkvist.

Salander first appeared in the 2005 novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (original Swedish title, Män som hatar kvinnor, literally "Men who hate women" in English). She reappeared in its sequels: The Girl Who Played with Fire (2006), The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets' Nest (2007), The Girl in the Spider's Web (2015), The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye (2017) and The Girl Who Lived Twice (2019).

Creation[]

In the only interview he ever did about the series, Larsson stated that he based the character of Lisbeth Salander on what he imagined Pippi Longstocking might have been like as an adult.[1][2] In the Millennium series, Salander has the name "V. Kulla" displayed on the door of her apartment on the top floor of Fiskargatan 9 in Stockholm. "V. Kulla" is an abbreviation of "Villa Villekulla", the name of Pippi Longstocking's house.[3]

Another source of inspiration was Larsson's niece, Therese. A rebellious teenager, she often wore black clothing and makeup, and told Larsson several times that she wanted to get a tattoo of a dragon. The author often emailed Therese while writing the novels to ask her about her life and how she would react in certain situations.[citation needed] She told him about her battle with anorexia and that she practiced kickboxing (previously jujitsu).[2][4]

After his death, many of Larsson's friends said the character was inspired by an incident in which Larsson, then a teenager, witnessed three of his friends gang-raping an acquaintance of his named Lisbeth, and he did nothing to stop it. Days later, wracked with guilt, he begged her forgiveness, which she refused to grant. The incident, he said, haunted him for years afterward, and in part moved him to create a character with her name who was also a rape survivor.[5] The veracity of this story has since been questioned, after a colleague from Expo magazine reported to Rolling Stone that Larsson had told him he had heard the story secondhand and retold it as his own.[2]

Character profile[]

Lisbeth Salander has red hair which she dyes raven black. Upon her first appearance in the series, she is described as "a pale, androgynous young woman who has hair as short as a fuse, and a pierced nose and eyebrows".

She has a wasp tattoo, about two centimeters long, on her neck, a tattooed loop around the bicep of her left arm, another loop around her left ankle, a Chinese symbol on her hip, and a rose on her left calf.[6] She has a large tattoo of a dragon on her back that runs from her shoulder, down her spine, and ends on her buttocks. This was changed in the English translation to a small dragon on her left shoulder blade.[7] Salander visits a clinic in Genoa between the first and second books, where she had her wasp tattoo removed as she felt it was "too conspicuous and it made her too easy to remember and identify". She also has a breast enlargement, having previously "been flat-chested, as if she had never reached puberty. She thought [her breasts] had looked ridiculous, and she was always uncomfortable showing herself naked".[8]

Salander is a world-class computer hacker. Under the pseudonym "Wasp", she becomes a prominent figure in the international hacker community known as the Hacker Republic (similar to the group Anonymous). She uses her computer skills as a means to earn a living, doing investigative work for Milton Security. She has an eidetic memory and is skillful at concealing her identity; she possesses passports in different names, and disguises herself to travel undetected around Sweden and worldwide.

Salander has a complicated relationship with investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist, which veers back and forth between romance and hostility throughout the series. She also has an on-again/off-again romantic relationship with Miriam "Mimi" Wu.

Personality[]

The survivor of a traumatic childhood, Salander is highly introverted and asocial, and has difficulty connecting to people and making friends. She is particularly hostile to men who abuse women, and takes special pleasure in exposing and punishing them. This is representative of Larsson's personal views and a major theme throughout the entire series.[9] In the series, Blomkvist speculates that Salander might have Asperger syndrome. Her mental state is never definitively described, an ambiguity that many antagonists in the series try to use against her: her sexually abusive public guardian, Nils Bjurman, describes her as "a sick, murderous, insane fucking person", while her one-time jailer Dr. Peter Teleborian describes her as "paranoid", "psychotic", "obsessive", and an "egomaniacal psychopath".[10]

On the other hand, Larsson stated that he thought that she might be looked upon as somewhat of an unusual kind of sociopath, due to her traumatic life experiences and inability to conform to social norms.[11]

In the book The Psychology of the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, on the question "Is Salander a psychopath?", Melissa Burkley, Ph.D. and Dr. Stephanie Mullins-Sweatt write: "Although Salander is antagonistic and violent, she doesn't appear to lack a conscience, which is the hallmark trait of a psychopath. While she may not always follow society's rules, she does have her own set of moral principles that abide by a code of right and wrong."[12]

At the end of the third book in the series Salander is declared sane and competent:

In the exhilarating court scene in The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest, Salander's lawyer, Anita (sic) Giannini, tramples Dr. Teleborian as she demonstrates that Lisbeth is 'just as sane and intelligent as anyone in this room.' This victory puts Lisbeth back on the right side of the asylum's doors, as her declaration of incompetence is rescinded, then and there. Sanity prevails."[13]

Writers have described Salander as a "fiercely unconventional and darkly kooky antiheroine",[11] a "superhero",[14] a "misfit", and "an androgynous, asocial, bisexually active... loner who makes a living as a computer hacker..."[15] Jennie Punter in Queen's Quarterly wrote that "the diminutive, flat-chested, chain-smoking, tattoo-adorned, anti-social, bisexual, genius computer hacker Lisbeth Salander" has become "one of the most compelling characters in recent popular fiction".[16]

Storyline in books[]

Millennium series[]

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo[]

In The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2005), Lisbeth Salander is introduced as a gifted, but deeply troubled, researcher and computer hacker working for Milton Security. Her boss, Dragan Armansky, commissions her to research disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist at the behest of a wealthy businessman, Henrik Vanger. When Blomkvist finds out that Salander hacked his computer, he hires her to assist him in investigating the disappearance of Vanger's grandniece, Harriet, 40 years earlier. Salander uses her research skills to uncover a series of murders, dating back decades and tied to Harriet's disappearance. During the investigation, Salander and Blomkvist become lovers.

The novel reveals Salander was declared legally incompetent as a child and is under the care of legal guardian Holgar Palmgren, one of the few people in the world she trusts and cares for. When Palmgren suffers a stroke, the court appoints her a new guardian: Nils Bjurman, a sadist who forces Salander to perform oral sex in return for access to her allowance. In a second sex session at his flat, he violently rapes and sodomizes her, unaware that she is recording his actions with a hidden camera. A few days later, she returns to his flat and, after disabling him with a taser, tapes his mouth and fastens him to his bed with his own bondage equipment, and finally sodomizes him with a huge anal plug. She then explains that she will release the video recording of him raping her if he does not do exactly what she orders, or if anything happens to her. She demands that he annul her legal incompetence and restore her sole access to her bank account. She tells him that she will visit him when she pleases, and if she ever finds him with a woman, even if she's there voluntarily, she will release the tape and destroy his life. Finally, she tattoos the words "I AM A SADISTIC PIG, A PERVERT, AND A RAPIST" on his abdomen, unlocks his handcuffs, and departs.

Salander eventually uncovers evidence that Harriet's late father, Gottfried, and her brother, Martin, committed the murders. Salander then finds Blomkvist just in time to save him from Martin, who is in the midst of torturing him. She pursues Martin on her motorcycle, but he is killed when he deliberately veers into an oncoming truck. Salander later uses her hacking skills to discover that Harriet Vanger is alive and hiding in Australia, and to get sensitive information about Blomkvist's arch-rival, corrupt media magnate Hans-Erik Wennerström. With the information uncovered by Salander, Blomkvist publishes an exposé article and book that ruins Wennerström and transform Blomkvist's magazine, Millennium, into one of the most respected and profitable in Sweden.

During her investigation of Wennerström, Salander uses her hacking skills and a series of disguises to withdraw billions of Swedish kronor from one of Wennerström's off-shore accounts. Salander anonymously reveals the address of Wennerström's final hideout to a lawyer with criminal connections, and Wennerström is murdered three days later.

At the end of the book, Salander acknowledges to herself that she has fallen in love with Blomkvist. On her way to tell him so, however, she sees him with his longtime lover, Millennium editor Erika Berger. Heartbroken, Salander abruptly cuts off all contact with him.

The Girl Who Played With Fire[]

The Girl Who Played With Fire (2006) begins with Salander's returning to Sweden after having traveled for a year. Shortly afterward, Salander is falsely implicated in the murder of three people: Bjurman and two of Blomkvist's colleagues. The frame-up is in fact a conspiracy between her biological father, former Soviet spy Alexander Zalachenko, and the Section, an illegal faction within Säpo, the Swedish Security Service, whose members had protected her father after he defected from the USSR. Zalachenko had been a high-ranking member of the GRU, and his defection was regarded by Säpo as an intelligence windfall, thus leading to the Section's covering up his subsequent illegal activities. Zalachenko had his son (and Salander's half-brother) Ronald Neidermann kill Blomkvist's colleagues, who were writing an exposé article on Zalachenko and Neidermann's prostitution ring, and Bjurman, a former Säpo employee who would have been exposed in the article as Salander's rapist. The Section then falsely incriminates Salander to cover up their concealment of Zalachenko's crimes.

Blomkvist tries to help Salander, even though she wants nothing to do with him. When she hacks into his computer, he leaves her his notes on the prostitution ring, from which she learns that Zalachenko is behind the frame-up. By the end of the novel, she tracks Zalachenko to his farm, where he shoots her in the head and has Neidermann bury her alive. She digs her way out, however, and hits her father in the face with an axe before losing consciousness. Blomkvist finds her and calls an ambulance, saving her life.

The novel expands upon Salander's childhood. She is portrayed as having been an extremely bright but asocial child who would violently lash out at anyone who threatened or picked on her. This was in part the result of a troubled home life; Zalachenko repeatedly beat her mother but escaped punishment because the Section perceived his value to the Swedish State as being more important than her mother's civil rights.

One day, when Salander was 12, Zalachenko beat her mother so badly that she sustained permanent brain damage. In retaliation, Salander hurled a homemade Molotov cocktail into her father's car, leaving him permanently disfigured and in chronic pain. The Section, fearing this would lead to their exposure, had the girl declared legally insane and sent to a Children's Psychiatric Hospital in Uppsala. While there, Salander was placed under the direct surveillance of psychiatrist Dr. Peter Teleborian, who had earlier conspired with the Section to have her declared insane. During her stay at the hospital, Teleborian put her in restraints for the most trivial infractions as a way of venting his repressed pedophilic urges. On the Section's orders, Teleborian declared Salander legally incompetent so that no one would ever believe her accounts of what they had done. They then had Bjurman, a lawyer in their employ, appointed as her guardian after Palmgren's stroke.

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets' Nest[]

In the third Millennium novel, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets' Nest (2007), Salander is arrested for the assault on Zalachenko, while she recuperates in the hospital. Zalachenko, who is a patient in the same hospital, is murdered by someone in the Section, who then tries to kill Salander; fortunately, Salander's lawyer (Annika Giannini, Blomkvist's sister) has barred the door. The would-be assassin then commits suicide.

Due to her deep-seated mistrust of authority, Salander refuses at first to cooperate in any way with her defense, relying instead on her friends in Sweden's hacker community. They eventually help Blomkvist discover the full scope of the Section's conspiracy, which he strives to publish at the risk of his own life. Salander eventually writes, and passes to Giannini, an exact description of the sexual abuse she suffered at Bjurman's hands, but written in such a way as to make it sound hallucinatory so as to mislead the prosecution.

At her trial, Salander is defiant and uncooperative. The prosecuting counsel uses testimony from Teleborian, appearing as their principal witness, to depict Salander as insane and in need of long-term care. Giannini then destroys Teleborian's credibility by introducing the recording of Salander's rape and produces extensive evidence of the Section's plot, published in Millennium that morning by Blomkvist. At the same time Giannini starts questioning Teleborian, the 10 members of the Section are arrested and charged with crimes against national security. Police briefly interrupt Salander's trial to arrest Teleborian for possession of child pornography, which Salander's fellow hackers uncovered from his laptop and sent to the authorities. Salander is set free the same day, her name cleared.

After she is cleared of the charges, Salander receives word that, as Zalachenko's daughter, she is entitled to a small inheritance and one of his properties. She refuses the money but goes to a disused brick factory she has inherited. She is attacked by Niedermann, who has been hiding there since shortly after the confrontation with Salander at Zalachenko's farm. She nails his feet to the floor and then calls the same motorcycle gang who attacked her in the previous novel, who want him dead because he killed some of their people. Before they arrive to kill Niedermann, she contacts the police.

That night, Blomkvist shows up at her door, and the two reconcile as friends.

Continuation novels[]

The Girl in the Spider's Web[]

In The Girl in the Spider's Web (2015), written by David Lagercrantz as a continuation of the original series, Salander is hired by scientist Frans Balder to find out who hacked his network and stole his quantum computer technology. She hacks into the network of his company, Solifon, and discovers that his data was stolen by a criminal organization called the "Spider Society", with help from accomplices within Solifon and the National Security Agency. When Balder is murdered, Salander, with Blomkvist's help, saves Balder's autistic son August from the Spider Society's assassins, and she is badly wounded in the process. She bonds with August, a fellow math prodigy, and becomes his protector.

Salander learns the Spider Society is led by her twin sister Camilla, a sociopath who as a child tormented her and delighted in the abuse their mother suffered at their father's hands. Camilla sends assassin Jan Holtster to kill Salander and August. Salander overpowers Holtster, however, and gives the police August's drawing of him. She has an opportunity to shoot Camilla during her escape, but cannot bring herself to kill her sister and allows her to get away.

Salander returns August to his mother, Hanna, kicks Hanna's abusive boyfriend out of the house, and gives Hanna and August plane tickets to Munich so they can start over. She then supplies Blomkvist with information she hacked from the NSA, which he uses to write an exposé article that results in the arrests of Camilla's accomplices and re-establishes Millennium as the most influential news magazine in Sweden. Salander shows up at Blomkvist's apartment, and they spend the night together.

The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye[]

In The Girl Who Takes an Eye for an Eye (2017), written by David Lagercrantz as a continuation of the original series.

The Girl Who Lived Twice (2019)[]

Lagercrantz' third and final novel in the series, The Girl Who Lived Twice, was published in 2019.

Portrayals in films[]

In 2009, the Swedish film and television studio Yellow Bird produced a trilogy of films based upon the first three novels. In these films, Salander is played as an adult by Noomi Rapace and as a child by Tehilla Blad. Rapace received a BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role nomination in 2011.

In the 2011 film adaptation of the first book, Salander is played by Rooney Mara, who received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress on January 24, 2012 for her performance.

In the 2018 movie The Girl in the Spider's Web, Salander is portrayed by Claire Foy.

Reception[]

David Denby of The New Yorker stated that the character of Lisbeth Salander clearly accounts for a large part of the novels' success.[17] Deirdre Donahue of USA Today referred to Salander as "one of the most startling, engaging and sometimes perplexing heroines in recent memory."[18] The New York Times's David Kamp called her "one of the most original characters in a thriller to come along in a while."[19] Likewise, Muriel Dobbin from The Washington Times dubbed her one of the most fascinating characters to emerge in crime fiction in years; "Her remoteness and her capacity for anger and violence are in contrast with a desperate vulnerability that she reveals only to the most unlikely of people."[20]

Reviewing the first Swedish film, Roger Ebert noted that it is "a compelling thriller to begin with, but it adds the rare quality of having a heroine more fascinating than the story".[21] The Independent's Jonathan Gibbs called the character "a vision of female empowerment – a kind of goth-geek Pippi Longstocking," but also an "agglomeration of clichés."[22] Richard Schickel of Los Angeles Times suggested that Salander represents something new in the thriller genre; "She's a tiny bundle of post-modernist tropes, beginning with her computer skills."[23]

Since 2015, there is a street named after Salander in Larsson's home town in north Sweden, Skellefteå. It is called Lisbeth Salanders gata and is surrounded by other names from local literature.[24][25]

References[]

- ^ Rising, Malin (17 February 2009). "Swedish Crime Writer Finds Fame After Death". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rich, Nathaniel (January 5, 2011). "The Mystery of the Dragon Tattoo: Stieg Larsson, the World's Bestselling — and Most Enigmatic — Author". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media LLC. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Lisbeth's new apartment". Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Lindqvist, Emma (25 February 2009). "Salanders förebild". Dagens Nyheter. Stockholm, Sweden: Bonnier AB. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ^ Penny, Laurie (5 September 2010). "Girls, tattoos and men who hate women". New Statesman. Bangkok, Thailand: NS Media Group. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Larsson, Stieg (2005). The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Norstedts Förlag. ISBN 978-0-307-47347-9.

- ^ Cochrane, Kira (4 October 2011). "Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy". The Guardian. London, England. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Larsson, Stieg (July 16, 2009). "Excerpt 'The Girl Who Played With Fire'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lopez Torregrosa, Luisita (July 10, 2010). "Lisbeth Salander, the Girl Who Rocked the Mystery-Action Genre". Politics Daily. New York City: AOL. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ^ Larsson, Stieg (2006). The Girl Who Played With Fire. Norstedts Förlag. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-0307949509.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ryan, Pat (May 22, 2010). "Pippi Longstocking, With Dragon Tattoo". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Burkley, Melissa; Mullins-Sweatt, Stephanie (January 3, 2012). "Is Lisbeth Salander a Psychopath?". Psychology Today. New York City: Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Martin, Aryn; Simms, Mary (November 2011). "Chapter 1: Labeling Lisbeth: Sti(e)gma and Spoiled Identity" (PDF). In Irwin, William; Bronson, Eric (eds.). The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Philosophy. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-0-470-94758-6.

- ^ Rosenberg, Robin S. (December 9, 2011). "Salander as Superhero: Is the Girl With the Dragon Tattoo a superhero?". Psychology Today. New York City: Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Peele, Stanton (December 16, 2011). "The World's -- and My -- Love Affair with Lisbeth Salander. Lisbeth Salander -- a misfit -- may be the most beloved figure in the world". Psychology Today. New York City: Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Punter, Jennie (Fall 2010). "Crime and Punishment in a Foreign Land". Queen's Quarterly. Kingston, Ontario: Queen's University. 117 (3): 380.

- ^ Denby, David (December 12, 2011). "Double Dare". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Donahue, Deirdre (July 27, 2009). "The Girl Who Played With Fire by Stieg Larsson: Book Review". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Kamp, David (May 28, 2010). "The Hacker and the Hack". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Dobbin, Muriel (June 25, 2010). "BOOK REVIEW: 'The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest'". The Washington Times. Washington DC: Washington Times LLC. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 17, 2010). "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois: Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved October 19, 2014 – via rogerebert.com.

- ^ Gibbs, Jonathan (24 February 2008). "The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, By Stieg Larsson - Reviews". The Independent. London, England: Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (February 24, 2008). "Book Review: 'The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest'". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Protokoll, kommunfullmäktige 2015-06-16 §185, Skellefteå

- ^ "Ormens väg och kvarteret Hjortronlandet". 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

External links[]

- The Stieg Larsson Trilogy from Quercus, publishers of Stieg Larsson

- The official Millennium site of Nordstedt Publishing

- Lisbeth Salander: The Movies Have Never Had a Heroine Quite Like Her - David Denby for The New Yorker, 2011/12/27

- Characters in novels of the 21st century

- Female characters in literature

- Female characters in film

- Literary characters introduced in 2005

- Fictional bisexual females

- Fictional hackers

- Fictional victims of child sexual abuse

- Fictional victims of sexual assault

- Fictional private investigators

- Fictional vigilantes

- Fictional characters with eidetic memory

- Fictional Swedish people

- Fictional Russian people

- Fictional kickboxers

- Fictional jujutsuka

- Fictional twins

- Fictional torturers

- Fictional LGBT characters in film

- Millennium (novel series)

- Thriller film characters

- Fictional LGBT characters in literature

- Dragon Tattoo Stories (film series)