Live Aid

| Live Aid | |

|---|---|

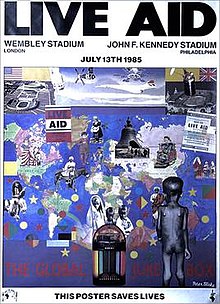

Official Live Aid poster, artwork by Peter Blake | |

| Genre | Pop Rock |

| Dates | 13 July 1985 |

| Location(s) | Wembley Stadium in London, England, United Kingdom John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Founded by | Bob Geldof Midge Ure |

| Attendance | 72,000 (London) 89,484 (Philadelphia) |

| Website | www |

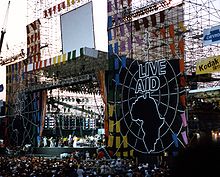

Live Aid was a benefit concert held on Saturday 13 July 1985, as well as a music-based fundraising initiative. The original event was organised by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to raise further funds for relief of the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, a movement that started with the release of the successful charity single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" in December 1984. Billed as the "global jukebox", Live Aid was held simultaneously at Wembley Stadium in London, UK, attended by about 72,000 people and John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, US, attended by 89,484 people.[1][2]

On the same day, concerts inspired by the initiative were held in other countries, such as the Soviet Union, Canada, Japan, Yugoslavia, Austria, Australia and West Germany. It was one of the largest satellite link-ups and television broadcasts of all time; an estimated audience of 1.9 billion, in 150 nations, watched the live broadcast, nearly 40 percent of the world population.[3][4]

The impact of Live Aid on famine relief has been debated for years. One aid relief worker stated that following the publicity generated by the concert, "humanitarian concern is now at the centre of foreign policy" for Western governments.[5] Geldof has said, "We took an issue that was nowhere on the political agenda and, through the lingua franca of the planet – which is not English but rock 'n' roll – we were able to address the intellectual absurdity and the moral repulsion of people dying of want in a world of surplus."[6] In another interview he stated that Live Aid "created something permanent and self-sustaining" but also asked why Africa is getting poorer.[5] The organisers of Live Aid tried to run aid efforts directly, channelling millions of pounds to NGOs in Ethiopia. It has been alleged that much of this went to the Ethiopian government of Mengistu Haile Mariam – a regime the UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher opposed[7] – and it is also alleged some funds were spent on guns.[5][8] The BBC stated in 2010 there was no evidence money had been diverted,[9] while the former British Ambassador to Ethiopia, Brian Barder, states, "the diversion of aid related only to the tiny proportion that was supplied by some NGOs to rebel-held areas."[10]

Background[]

The 1985 Live Aid concert was conceived as a follow-on to the successful charity single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" which was also the brainchild of Geldof and Ure. In October 1984, images of hundreds of thousands of people starving to death in Ethiopia were shown in the UK in Michael Buerk's BBC News reports on the 1984 famine.[11] The BBC News crew were the first to document the famine, with Buerk's report on 23 October describing it as "a biblical famine in the 20th century" and "the closest thing to hell on Earth".[12] The reports featured a young nurse, Claire Bertschinger, who, surrounded by 85,000 starving people, told of her sorrow of having to decide which children would be allowed access to the limited food supplies in the feeding station and which were too sick to be saved.[13] She would put a little mark on the children who got chosen, with Geldof stating of her at the time, "In her was vested the power of life and death. She had become God-like and that is unbearable for anyone."[13] Traumatised by what she experienced she didn’t speak about it for two decades, recalling in 2005, "I felt like a Nazi sending people to the death camps. Why was I in this situation? Why was it possible in this time of plenty that some have food and some do not? It is not right".[13]

"There are thousands of people outside. I have counted 10 rows and each row has more than 100 people in and I can only take 60-70 children today, but they all need to come in.“

—1984 diary entry from nurse Claire Bertschinger outside a feeding station.[13]

Shocked by the report, the British public inundated relief agencies, such as Save the Children, with donations, with the report also bringing the world's attention to the crisis in Ethiopia.[11][14] Such was the magnitude of Buerk's report it was also broadcast in its entirety on a major US news channel—almost unheard of at the time.[15] From his home in London Geldof also saw the report, and called Ure from Ultravox (Geldof and Ure had previously worked together for charity when they appeared at the 1981 benefit show The Secret Policeman's Ball in London) and together they quickly co-wrote the song, "Do They Know It's Christmas?" in the hope of raising money for famine relief.[11] Geldof then contacted colleagues in the music industry and persuaded them to record the single under the title 'Band Aid' for free.[11] On 25 November 1984, the song was recorded at Sarm West Studios in Notting Hill, London, and was released four days later.[16][17] It stayed at number one for five weeks in the UK, was Christmas number one, and became the fastest-selling single ever in Britain and raised £8 million, rather than the £70,000 Geldof and Ure had initially expected.[11] Geldof then set his sights on staging a huge concert to raise further funds.[11]

The idea to stage a charity concert to raise more funds for Ethiopia originally came from Boy George, the lead singer of Culture Club. George and Culture Club drummer Jon Moss had taken part in the recording of "Do They Know It's Christmas?" and in the same month, the band were undertaking a tour of the UK, which culminated in six nights at Wembley Arena. On the final night at Wembley, 22 December 1984, an impromptu gathering of some of the other artists from Band Aid joined Culture Club on stage at the end of the concert for an encore of "Do They Know It's Christmas?". George was so overcome by the occasion he told Geldof that they should consider organising a benefit concert. Speaking to the UK music magazine Melody Maker at the beginning of January 1985, Geldof revealed his enthusiasm for George's idea, saying, "If George is organising it, you can tell him he can call me at any time and I'll do it. It's a logical progression from the record, but the point is you don't just talk about it, you go ahead and do it!"[18]

It was clear from the interview that Geldof had already had the idea to hold a dual venue concert and how the concerts should be structured:

The show should be as big as is humanly possible. There's no point just 5,000 fans turning up at Wembley; we need to have Wembley linked with Madison Square Gardens, and the whole show to be televised worldwide. It would be great for Duran to play three or four numbers at Wembley, and then flick to Madison Square where Springsteen would be playing. While he's on, the Wembley stage could be made ready for the next British act like the Thompsons or whoever. In that way, lots of acts could be featured and the television rights, tickets and so on could raise a phenomenal amount of money. It's not an impossible idea, and certainly one worth exploiting.[18]

On how Geldof got artists to agree to play, Live Aid production manager Andy Zweck states, "Bob had to play some tricks to get artists involved. He had to call Elton and say Queen are in and Bowie's in, and of course they weren't. Then he'd call Bowie and say Elton and Queen are in. It was a game of bluff."[19]

Organisation[]

Among those involved in organising Live Aid were Harvey Goldsmith, who was responsible for the Wembley Stadium concert, and Bill Graham, who put together the American leg.[20] On promoting the event, Goldsmith states, "I didn't really get a chance to say no. Bob [Geldof] arrived in my office and basically said, 'We're doing this.' It started from there."[19]

The concert grew in scope, as more acts were added on both sides of the Atlantic. Tony Verna, inventor of instant replay, was able to secure John F. Kennedy Stadium through his friendship with Philadelphia Mayor Goode and was able to procure, through his connections with ABC's prime time chief, John Hamlin, a three-hour prime time slot on the ABC Network and, in addition, was able to supplement the lengthy program through meetings that resulted in the addition of an ad-hoc network within the US, which covered 85 per cent of TVs there. Verna designed the needed satellite schematic and became the Executive Director as well as the Co-Executive Producer along with Hal Uplinger. Uplinger came up with the idea to produce a four-hour video edit of Live Aid to distribute to those countries without the necessary satellite equipment to rebroadcast the live feed.

Collaborative effort[]

The concert began at 12:00 British Summer Time (BST) (7:00 Eastern Daylight Time (EDT)) at Wembley Stadium in the United Kingdom.[21] It continued at John F. Kennedy Stadium (JFK) in the United States, starting at 13:51 BST (8:51 EDT). The UK's Wembley performances ended at 22:00 BST (17:00 EDT). The JFK performances and whole concert in the US ended at 04:05 BST 14 July (23:05 EDT). Thus, the concert continued for just over 16 hours, but since many artists' performances were conducted simultaneously in Wembley and JFK, the total concert's length was much longer.[21]

Mick Jagger and David Bowie intended to perform a transatlantic duet, with Bowie in London and Jagger in Philadelphia.[22] Problems of synchronisation meant the only practical solution was to have one artist, likely Bowie at Wembley, mime along to prerecorded vocals broadcast as part of the live sound mix for Jagger's performance from Philadelphia.[22] Veteran music engineer David Richards (Pink Floyd and Queen) was brought in to create footage and sound mixes Jagger and Bowie could perform to in their respective venues. The BBC would then have had to ensure those footage and sound mixes were in sync while also performing a live vision mix of the footage from both venues. The combined footage would then have had to be bounced back by satellite to the various broadcasters around the world. Due to the time lag (the signal would take several seconds to be broadcast twice across the Atlantic Ocean), Richards concluded there was no way for Jagger to hear or see Bowie's performance, meaning there could be no interaction between the artists, essentially defeating the whole point of the exercise. On top of this, both artists objected to the idea of miming at what was perceived as a historic event. Instead, Jagger and Bowie worked with Richards to create a video of the song they would have performed, a cover of "Dancing in the Street", which was shown on the screens of both stadiums and broadcast as part of many TV networks' coverage.[22]

Each of the two main parts of the concert ended with their particular continental all-star anti-hunger anthems, with Band Aid's "Do They Know It's Christmas?" closing the UK concert, and USA for Africa's "We Are the World" closing the US concert (and thus the entire event itself).[23]

Concert organisers have subsequently said they were particularly keen to ensure at least one surviving member of the Beatles, ideally Paul McCartney, took part in the concert as they felt that having an 'elder statesman' from British music would give it greater legitimacy in the eyes of the political leaders whose opinions the performers were trying to shape. McCartney agreed to perform and has said it was "the management" – his children – who persuaded him to take part. In the event, he was the last performer (aside from the Band Aid finale) to take to the stage and one of the few to be beset by technical difficulties; his microphone failed for the first two minutes of his piano performance of "Let It Be", making it difficult for television viewers and impossible for those in the stadium to hear him.[3] He later joked by saying he had thought about changing the lyrics to "There will be some feedback, let it be".[24]

Phil Collins performed at both Wembley Stadium and JFK, travelling by helicopter (piloted by UK TV personality Noel Edmonds) to London Heathrow Airport, then by Concorde to New York City, and by another helicopter to Philadelphia.[25] As well as his own set at both venues, he also played the drums for Eric Clapton, and played with the reuniting surviving members of Led Zeppelin at JFK. On the Concorde flight, Collins encountered actress and singer Cher, who was unaware of the concerts. Upon reaching the US, she attended the Philadelphia concert and can be seen performing as part of the concert's "We Are the World" finale.[19] In a 1985 interview, singer-songwriter Billy Joel stated that he had considered performing at the event, but ultimately chose not to because he had difficulties getting his band together and didn't want to perform by himself.[26]

Broadcasts[]

Broadcaster Richard Skinner opened the Live Aid concert with the words:

It's twelve noon in London, seven AM in Philadelphia, and around the world it's time for Live Aid.[21]

The concert was the most ambitious international satellite television venture that had ever been attempted at the time. In Europe, the TV feed was supplied by the BBC, whose broadcast was presented by Richard Skinner, Andy Kershaw, Mark Ellen, David Hepworth, Andy Batten-Foster, Steve Blacknell, Paul Gambaccini, Janice Long and Mike Smith and included numerous interviews and chats in between the various acts.[27] The BBC's television sound feed was mono, as was all UK TV audio before NICAM was introduced, but the BBC Radio 1 feed was stereo and was simulcast in sync with the TV pictures. Unfortunately, in the rush to set up the transatlantic feeds, the sound feed from Philadelphia was sent to London via transatlantic cable, while the video feed was via satellite, which meant a lack of synchronisation on British television receivers. Due to the constant activities in both London and Philadelphia, the BBC producers omitted the reunion of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young from their broadcast. The BBC, however, did supply a 'clean feed' to various television channels in Europe.

ABC was largely responsible for the US broadcast (although ABC themselves only telecast the final three hours of the concert from Philadelphia, hosted by Dick Clark, with the rest shown in syndication through Orbis Communications, acting on behalf of ABC). An entirely separate and simultaneous US feed was provided for cable viewers by MTV, whose broadcast was presented in stereo, and accessible as such for those with stereo televisions. At the time, before multichannel television sound was enacted nationwide, very few televisions reproduced stereo signals and few television stations were able to broadcast in stereo. While the telecast was run advertisement-free by the BBC, both the MTV and syndicated/ABC broadcasts included advertisements and interviews. As a result, many songs were omitted due to the commercial breaks, as these songs were played during these slots.

The biggest issue of the syndicated/ABC coverage is that the network had wanted to reserve some of the biggest acts that had played earlier in the day for certain points in the entire broadcast, particularly in the final three hours in prime time; thus, Orbis Communications had some sequences replaced by others, especially those portions of the concert that had acts from London and Philadelphia playing simultaneously. For example, while the London/Wembley finale was taking place at 22:00 (10:00 pm) London time, syndicated viewers saw segments that had been recorded earlier, so that ABC could show the UK finale during its prime-time portion. In 1995, VH1 and MuchMusic aired a re-edited ten-hour re-broadcast of the concert for its 10th anniversary.

The Live Aid concert in London was also the first time that the BBC outside broadcast sound equipment had been used for an event of such scale. In stark contrast to the mirrored sound systems commonly used by the rock band touring engineers, with two 40–48-channel mixing consoles at the front of house and another pair for monitors, the BBC sound engineers had to use multiple 12-channel desks. Some credit this as the point where the mainstream entertainment industry realised that the rock concert industry had overtaken them in technical expertise.[28]

Stages and locations[]

Wembley Stadium[]

The Coldstream Guards band opened with the "Royal Salute", a brief version of the national anthem "God Save the Queen". Status Quo were the first act to appear and started their set with "Rockin' All Over the World", also playing "Caroline" and fan favourite "Don't Waste My Time".[29] "Bob told me, 'It doesn't matter a fuck what you sound like, just so long as you're there,'" recalled guitarist and singer Francis Rossi. "Thanks for the fucking honesty, Sir Bob."[30] This would be the band's last appearance with bassist and founder member Alan Lancaster and drummer Pete Kircher.[31] Princess Diana and Prince Charles were among those in attendance as the concert commenced.[11]

Bob Geldof performed with the rest of the Boomtown Rats, singing "I Don't Like Mondays". He stopped just after the line "The lesson today is how to die" to loud applause.[3][19] According to Gary Kemp, "Dare I say it, it was evangelical, that moment when Geldof stopped 'I Don't Like Mondays' and raised his fist in the air. He was a sort of statesman. A link between punk and the New Romantics and the Eighties. You would follow him. He just has a huge charisma; he'd make a frightening politician.“[19] He finished the song and left the crowd to sing the final words. Elvis Costello sang a version of the Beatles' "All You Need Is Love", which he introduced by asking the audience to "help [him] sing this old northern English folk song".[32]

Queen's twenty-one minute performance, which began at 6:41 pm, was voted the greatest live performance in the history of rock in a 2005 industry poll of more than 60 artists, journalists and music industry executives.[33][34] Queen's lead singer Freddie Mercury at times led the crowd in unison refrains,[35] and his sustained note—"Aaaaaay-o"—during the a cappella section came to be known as "The Note Heard Round the World".[36][37] The band's six-song set opened with a shortened version of "Bohemian Rhapsody" and closed with "We Are the Champions".[3][38][39] Mercury and fellow band member Brian May later sang the first song of the three-part Wembley event finale, "Is This the World We Created...?"[39]

Other well-received performances on the day included those by U2 and David Bowie. The Guardian cited Live Aid as the event that made stars of U2.[40] The band played a 12-minute rendition of "Bad". The length of "Bad" limited them to two songs; a third, "Pride (In the Name of Love)", had to be dropped. During "Bad", vocalist Bono jumped off the stage to join the crowd and dance with a teenage girl. In July 2005, the woman said that he had saved her life. She was being crushed by people pushing forwards; Bono saw this, and gestured frantically at the ushers to help her. They did not understand what he was saying, and so he jumped down to help her himself.[41] Describing Bowie's performance, Rolling Stone observed “as approximately two billion people sang along to “Heroes”, he seemed like one of the biggest and most vital rock stars in the world."[42] Dire Straits and Phil Collins (both accompanied by Sting) also received praise for their performances at Wembley.[25][43]

"One afternoon before the concert, Bowie was up in the office and we started looking through some videos of news footage, and we watched the CBC piece [footage from the Ethiopian famine, cut to the Cars' song "Drive“]. Everyone just stopped. Bowie said, 'You've got to put that in the show, it's the most dramatic thing I've ever seen.’ That was probably one of the most evocative things in the whole show and really got the money rolling in."

—Live Aid promoter Harvey Goldsmith on Bowie picking out the CBC news piece for the concert, a video Bowie introduced on the big screen at Wembley after his set.[19]

The transatlantic broadcast from Wembley Stadium suffered technical problems and failed during The Who's performance of their opening song "My Generation", immediately after Roger Daltrey sang "Why don't you all fade ..." (the last word "away" was cut off when a blown fuse caused the Wembley stage TV feed to temporarily fail).[3] The broadcast returned as the last verse of "Pinball Wizard" was played. John Entwistle's bass wouldn't work at the start, causing an awkward delay of over a minute before they could start playing. The band played with Kenney Jones on drums and it was their first performance since disbanding after a 1982 'farewell' tour. The Who's performance was described as "rough but right" by Rolling Stone, but they would not perform together again for another three years.[44] At 32 minutes Elton John had the longest set on the day;[45] his setlist included the first performance of "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me" with George Michael.[46]

While performing "Let It Be" near the end of the Wembley show, the microphone mounted to Paul McCartney’s piano failed for the first two minutes of the song, making it difficult for television viewers and the stadium audience to hear him.[3] During this performance, the TV audience were better off, audio-wise, than the stadium audience, as the TV sound was picked up from other microphones near McCartney. The stadium audience, who could obviously not hear the electronic sound feed from these mics, unless they had portable TV sets and radios, drowned out what little sound from McCartney could be heard during this part of his performance. As a result, organiser and performer Bob Geldof, accompanied by earlier performers David Bowie, Alison Moyet and Pete Townshend returned to the stage to sing with him and back him up (as did the stadium audience despite not being able to hear much), by which time McCartney's microphone had been repaired.[47]

At the conclusion of the Wembley performances, Bob Geldof was raised onto the shoulders of the Who's guitarist Pete Townshend and Paul McCartney.[48] Geldof had stated he "hasn’t slept in weeks" in the lead up to the concert, and when asked what his plans were post-Live Aid, he told an interviewer, "I’m going to go home and sleep."[49]

The Wembley speaker system was provided by Hill Pro Audio. It consisted primarily of the Hill J-Series Mixing Consoles, Hill M3 Speaker System powered by the Hill 3000 amplifiers.[50] In an interview with Studio Sound in December 1985, Malcolm Hill described the concept for the system in detail.[51]

John F. Kennedy Stadium[]

The host of the televised portion of the concert in Philadelphia was actor Jack Nicholson. The opening artist Joan Baez announced to the crowd, "this is your Woodstock, and it's long overdue," before leading the crowd in singing "Amazing Grace" and "We Are the World".[52]

When Madonna got on stage, despite the 95 °F (35 °C) ambient temperature, she proclaimed "I ain't taking shit off today!" referring to the recent release of early nude photos of her in Playboy and Penthouse magazines.[53]

During his opening number, "American Girl", Tom Petty flipped the middle finger to somebody off stage about one minute into the song. Petty stated the song was a last-minute addition when the band realised that they would be the first act to play the American side of the concert after the London finale and "since this is, after all, JFK Stadium".[54]

When Bob Dylan broke a guitar string, while playing with the Rolling Stones members Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood, Wood took off his own guitar and gave it to Dylan. Wood was left standing on stage guitarless. After shrugging to the audience, he played air guitar, even mimicking the Who's Pete Townshend by swinging his arm in wide circles, until a stagehand brought him a replacement. The performance was included in the DVD, including the guitar switch and Wood talking to stage hands, but much of the footage used was close-ups of either Dylan or Richards.

During their duet on the reprise of "It's Only Rock 'n' Roll", Mick Jagger ripped away part of Tina Turner's dress, leaving her to finish the song in what was, effectively, a leotard.[55]

The JFK portion included reunions of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the original Black Sabbath with Ozzy Osbourne, the Beach Boys with Brian Wilson, and surviving members of Led Zeppelin, with Phil Collins and the Power Station (and former Chic) member Tony Thompson sharing duties on drums in place of the band's late drummer John Bonham (although they were not officially announced by their group name from the stage, but were announced as Led Zeppelin on the VH1 10th Anniversary re-broadcast in 1995).[56]

Teddy Pendergrass made his first public appearance since his near-fatal car accident in 1982 which paralysed him. Pendergrass, along with Ashford & Simpson, performed "Reach Out and Touch".[57] Bryan Adams (who came on after Judas Priest), recalled "it was bedlam backstage", before performing a four-song set, including "Summer of '69".[19]

Duran Duran performed a four-song set which was the final time the five original band members would publicly perform together until 2003. Their set saw a weak, off-key falsetto note hit by frontman Simon Le Bon during "A View to a Kill". The error was dubbed "The Bum Note Heard Round the World" by various media outlets,[34][58] in contrast to Freddie Mercury's "Note Heard Round the World" at Wembley.[34] Le Bon later recalled it was the most embarrassing moment of his career.[58]

The UK TV feed from Philadelphia was dogged by an intermittent buzzing on the sound during Bryan Adams' turn on stage and continued less frequently throughout the rest of the UK reception of the American concert and both the audio and video feed failed entirely during that performance and during Simple Minds' performance.

Phil Collins, who had performed in London earlier in the day, began his solo set with the quip, "I was in England this afternoon. Funny old world, innit?" to cheers from the Philadelphia crowd.[25] Collins played drums during Eric Clapton’s 17 minute set, which included well received performances of "Layla" and "White Room".[59]

Fundraising[]

Throughout the concerts, viewers were urged to donate money to the Live Aid cause. Three hundred phone lines were manned by the BBC, so that members of the public could make donations using their credit cards. The phone number and an address that viewers could send cheques to were repeated every twenty minutes.

Nearly seven hours into the concert in London, Bob Geldof enquired how much money had been raised so far; he was told about £1.2 million. He is said to have been sorely disappointed by the amount and marched to the BBC commentary position. Pumped up further by a performance by Queen which he later called "absolutely amazing", Geldof gave an interview in which BBC presenter David Hepworth had attempted to provide a postal address to which potential donations could be sent; Geldof interrupted him in mid-flow and shouted "Fuck the address, let's get the numbers". Although the phrase "give us your fucking money" has passed into folklore, Geldof has stated that it was never uttered.[60] Private Eye magazine made great humorous capital out of this outburst, emphasising Geldof's Irish accent which meant the profanities were heard as "fock" or "focking". After the outburst, donations increased to £300 per second.[61]

Later in the evening, following David Bowie's set, a video shot by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was shown to the audiences in London and Philadelphia, as well as on televisions around the world (though neither US feed showed the film), showing starving and diseased Ethiopian children set to "Drive" by The Cars. (This would also be shown at the London Live 8 concert in 2005.[62]) The rate of donations became faster in the aftermath of the video. Geldof had previously refused to allow the video to be shown, due to time constraints, and had only relented when Bowie offered to drop the song "Five Years" from his set as a trade-off.[63]

Geldof mentioned during the concert that the Republic of Ireland gave the most donations per capita, despite being in the midst of a serious economic recession. The largest donation came from Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, who was part of the ruling family of Dubai, who donated £1m in a phone conversation with Geldof. The next day, news reports stated that between £40 and £50 million had been raised. It is now estimated that around £150 million in total has been raised for famine relief as a direct result of the concerts.

Criticisms and controversies[]

Bob Dylan's performance generated controversy; while transitioning from "Ballad of Hollis Brown" to "When the Ship Comes In," he said: "I hope that some of the money ... maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe ... one or two million, maybe ... and use it, say, to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks".[3] He is often misquoted, as on the Farm Aid website,[64] as saying: "Wouldn't it be great if we did something for our own farmers right here in America?". In his autobiography, Is That It? (published in 1986), Geldof was critical of the remark, saying "He displayed a complete lack of understanding of the issues raised by Live Aid. ... Live Aid was about people losing their lives. There is a radical difference between losing your livelihood and losing your life. It did instigate Farm Aid, which was a good thing in itself, but it was a crass, stupid, and nationalistic thing to say."[65] Although Dylan's comments were criticised, his remark inspired fellow musicians Willie Nelson, Neil Young and John Mellencamp to organise the Farm Aid charity, which held its first concert in September 1985.[66][67] The concert raised over $9 million for America's family farmers and became an annual event.[68]

Geldof was not happy about the Hooters being added as the opening band in Philadelphia. He felt pressured into it by Graham and local promoter Larry Magid. Magid, promoting the concert through Electric Factory Concerts, argued that the band was popular in Philadelphia; their first major label album Nervous Night had been released almost three months earlier and had been a hit. In an interview for Rolling Stone, Geldof asked: "Who the fuck are the Hooters?"[69] Ironically, in December 2004, Geldof appeared on the bill with the Hooters in Germany as their opening act.[69]

Adam Ant subsequently criticised the event and expressed regrets about playing it, saying, "I was asked by Sir Bob [sic] to promote this concert. They had no idea they could sell it out. Then in Bob's book he said, 'Adam was over the hill so I let him have one number.' ... Doing that show was the biggest fucking mistake in the world. Knighthoods were made, Bono got it made, and it was a waste of fucking time. It was the end of rock 'n' roll."[70] Geldof stated in his autobiography that Miles Copeland, manager of Adam Ant and Sting, asked Geldof if he'd thought of asking Ant after Geldof contacted him to get Sting to appear: "I hadn't. I thought he was a bit passé. But then so were the Boomtown Rats, and each represented a certain piece of pop history, so I agreed. I also thought that might entice him to encourage Sting, or perhaps all three of the Police."[71]

BBC coverage co-host Andy Kershaw was heavily critical of the event in his autobiography No Off Switch, stating, "Musically, Live Aid was to be entirely predictable and boring. As they were wheeled out – or rather bullied by Geldof into playing – it became clear that this was another parade of the same old rock aristocracy in a concert for Africa, organised by someone who, while advertising his concern for, and sympathy with, the continent didn't see fit to celebrate or dignify the place by including on the Live Aid bill a single African performer." Kershaw also described the event as "irritating, shallow, sanctimonious and self-satisfied" for failing to confront the fundamental causes of the famine and being "smug in its assumption that a bunch of largely lamentable rock and pop floozies was capable of making a difference, without tackling simultaneously underlying problems".[72]

Led Zeppelin reunion[]

"I thought it was just going to be low-key and we’d all get together and have a play. But something happened between that conversation and the day – it became a Led Zeppelin reunion."

—Phil Collins on the Led Zeppelin performance[73]

Led Zeppelin performed for the first time since the death of their drummer John Bonham in 1980. Two drummers filled in for Bonham: Phil Collins, who had played on singer Robert Plant's first two solo albums, and Tony Thompson. The performance was criticised for Plant's hoarse voice, Jimmy Page's out-of-tune guitar, a lack of rehearsal, and poorly functioning monitors. Plant described the performance as "a fucking atrocity for us. ... It made us look like loonies."[74]

Page later criticised Collins' performance, saying: "Robert told me Phil Collins wanted to play with us. I told him that was all right if he knows the numbers. But at the end of the day, he didn't know anything. We played 'Whole Lotta Love', and he was just there bashing away cluelessly and grinning. I thought that was really a joke."[75] Collins responded: "It wasn't my fault it was crap... If I could have walked off, I would have. But then we'd all be talking about why Phil Collins walked off Live Aid – so I just stuck it out... I turned up and I was a square peg in a round hole. Robert was happy to see me, but Jimmy wasn't."[73]

Led Zeppelin have blocked broadcasts of the performance and withheld permission for it to be included on the DVD release.[76] Philadelphia named it "one of the worst rock-and-roll reunions of all time", with Victor Fiorillo writing: "I'd like to be able to blame all of the awfulness on anaemic Phil Collins, who sat in on drums, and Page himself later fingered the Genesis drummer for screwing up the set. But Collins was just the beginning of the bad. Go ahead. Watch and remember. It really was that terrible."[77]

Fund use in Ethiopia[]

In 1986, Spin published an exposé on the realities of Live Aid's actions in Ethiopia. They claimed that Geldof deliberately ignored warnings from Médecins Sans Frontières, who had complained directly to Geldof even before Live Aid, about the role of the Ethiopian Government under Derg leader Mengistu Haile Mariam in causing the famine and that by working with Mengistu directly, much of the relief funds intended for victims were in fact siphoned off to purchase arms from the Soviet Union, thereby exacerbating the situation even more. Geldof responded by deriding both the articles and Médecins Sans Frontières, who had been expelled from the country, and reportedly saying, "I'll shake hands with the Devil on my left and on my right to get to the people we are meant to help".[78][79]

According to the BBC World Service, a certain proportion of the funds were siphoned off to buy arms for the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front.[80] This coalition battled at the time against Derg. The Band Aid Trust complained to the BBC Editorial Complaints Unit regarding the specific allegations in the BBC World Service documentary, and their complaint was upheld.[81] In 2010 the BBC issued an apology to the Trust and stated there was no evidence money had been diverted,[9] while the former British Ambassador to Ethiopia, Brian Barder, states, "the diversion of aid related only to the tiny proportion that was supplied by some NGOs to rebel-held areas."[10]

Although a professed admirer of Geldof's generosity and concern, American television commentator Bill O'Reilly was critical of the Live Aid's oversight of the use of the funds raised. O'Reilly believed that charity organizations, operating in aid-receiving countries, should control donations, rather than "chaotic nations."[82] Arguing that Live Aid accomplished good ends while inadvertently causing harm at the same time, David Rieff gave a presentation of similar concerns in The Guardian at the time of Live 8.[83]

Tim Russert, in an interview on Meet the Press shortly after O'Reilly's comments, addressed these concerns to Bono. Bono responded that corruption, not disease or famine, was the greatest threat to Africa, agreeing with the belief that foreign relief organisations should decide how the money is spent. On the other hand, Bono said that it was better to spill some funds into nefarious quarters for the sake of those who needed it than to stifle aid because of possible theft.[84]

Performances[]

Live Aid recordings[]

When organiser Bob Geldof was persuading artists to take part in the concert, he promised them that it would be a one-off event, never to be seen again. That was the reason why the concert was never recorded in its complete original form, and only secondary television broadcasts were recorded. Following Geldof's request, ABC erased its own broadcast tapes.[98] However, before the syndicated/ABC footage was erased, copies of it were donated to the Smithsonian Institution and have now been presumed lost. The ABC feed of the USA for Africa/"We Are The World" finale does exist in its entirety, complete with the network end credits, and can be found as a supplemental feature on the We Are The World: The Story Behind The Song DVD.

Meanwhile, MTV decided to keep recordings of its broadcast and eventually located more than 100 tapes of Live Aid in its archives, but many songs in these tapes were cut short by MTV's ad breaks and presenters (according to the BBC).[99] Many performances from the US were not shown on the BBC, and recordings of these performances are missing. There were four separate Audio Trucks in Philadelphia provided by David Hewitt of Remote Recording Services. ABC had taken the decision that no multi track tape recordings would be allowed, so no remixing of the Philadelphia show was possible.

Official Live Aid DVD[]

An official four-disc DVD set of the Live Aid concerts was released on 8 November 2004. A premiere to launch the new DVD was held on 7 November and shown in DTS surround sound featuring a short compilation of the four-disc set. The screening was held at the Odeon Cinema in Kensington, London and included guests such as Brian May, Anita Dobson, Roger Taylor, Bob Geldof and partner Jean Marie, Annie Lennox, Midge Ure, Michael Buerk, Gary Kemp and The Darkness.[100] Other theatrical premieres were held in Zurich, Milan, Rome, Vienna, Hamburg and Berlin.[101] A 52-minute compilation was later released as a limited edition DVD in July 2005 titled 20 Years Ago Today: Live Aid.[102] The box set contains 10-hour partial footage of the 16-hour length concert. The DVD was produced by Geldof's company, Woodcharm Ltd., and distributed by Warner Music Vision. The DVD has since been out of print and no longer available in stores. The decision to finally release it was taken by Bob Geldof nearly 20 years after the original concerts, after he found a number of unlicensed copies of the concert on the Internet.[103]

The most complete footage that exists is used from the BBC source, and this was the main source of the DVD. During production on the official DVD, MTV lent Woodcharm Ltd. their B-roll and alternate camera footage where MTV provided extra footage of the Philadelphia concert (where ABC had erased the tapes from the command of Bob Geldof). Songs that were not originally littered with ads were also used on the official DVD.

Working from the BBC and MTV footage, several degrees of dramatic licence were taken, to release the concert on DVD. Many songs had their soundtracks altered for the DVD release, mainly in sequences where there were originally microphone problems. In one of those instances, Paul McCartney had re-recorded his failed vocals for "Let It Be" in a studio the day after the concert (14 July 1985) but it was never used until the release of the DVD. Also, in the US finale, the original USA for Africa studio track for "We Are the World" was overlaid in places where the microphone was absent (consequently, it includes the vocals of Kenny Rogers and James Ingram, two artists who did not even take part in Live Aid).

Some artists did not want their performances to be featured on the DVD. At their own request, Led Zeppelin and Santana were omitted. The former defended their decision not to be included on the grounds that their performance was 'sub-standard', but to lend their support, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant pledged to donate proceeds from the DVD release of Page & Plant: No Quarter to the campaign, and John Paul Jones pledged proceeds from his American tour with Mutual Admiration Society.[104]

Judicious decisions were also made on which acts would be included and which ones would not, due to either technical difficulties in the original performances, the absence of original footage, or for music rights reasons. Rick Springfield, the Four Tops, the Hooters, the Power Station, Billy Ocean and Kool and the Gang were among those acts that were left off the DVD. Several artists who did feature on the DVD also had songs that were performed omitted. Madonna performed three solo songs in the concert, but only two were included on the DVD ("Love Makes the World Go Round" was omitted). Phil Collins played "Against All Odds" and "In the Air Tonight" at both Wembley and JFK, but only the London performance of the former and the Philadelphia performance of the latter were included on the DVD. The JFK performance of "Against All Odds" was later included on Collins' Finally ... The First Farewell Tour DVD. Tom Petty performed four songs, and only two were included on DVD. Patti LaBelle played six songs but only two songs were included.

In 2007, Queen released a special edition of Queen Rock Montreal on Blu-ray and DVD formats containing their 1981 concert from The Forum in Montreal, Canada, and their complete Live Aid performance, along with Freddie Mercury and Brian May performing "Is This the World We Created...?" from the UK Live Aid finale, all re-mixed in DTS 5.1 sound by Justin Shirley-Smith. Also included is their Live Aid rehearsal, and an interview with the band, from earlier in the week.

On its release, the then British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, decided the VAT collected on sales of the Live Aid DVD would be given back to the charity, which would raise an extra £5 for every DVD sold.

On 14 November 2004, the DVD entered the UK Official Music Video Chart at number one and stayed in the top position for twelve consecutive weeks.[105]

Charts[]

| Charts (2004) | Peak position |

Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Dutch Music DVDs Chart | 2 | [106] |

| Spanish Music DVD Chart (Promusicae) | 8 | [107] |

| UK Music Video Chart (OCC) | 1 | [105] |

| US Top Music Video (Billboard) | 2 | [108] |

Certifications[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[109] | 2× Platinum | 30,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[110] | Gold | 5,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[111] | 2× Diamond | 200,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[112] | Platinum | 15,000* |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[113] | Platinum | 6,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[114] | 6× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[115] | 10× Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Official Live Aid audio[]

An audio copy of Live Aid was officially released by the Band Aid Trust label on 7 September 2018 on digital download. When first released in 2018, the Queen performance was excluded. The band's set was, however, later included as a part of the digital download in May 2019. It has a total of ninety-three audio tracks.[116]

Live Aid channel[]

On 12 September 2018, YouTube launched the Official Live Aid channel with a total of 87 videos from the Live Aid 1985 concert. According to the channel, all earnings from viewings go to the Band Aid Trust.[117] As with the digital download release, a few notable performances are not included for unknown reasons, although Queen's set was uploaded to the channel with its inclusion on the digital download.

Unofficial recordings[]

Because the Live Aid broadcast was watched by 1.5 billion people,[118] most of the footage was recorded on home consumer video recorders all around the world, in various qualities. Many of these recordings were in mono, because in the mid-1980s most home video machines could only record mono sound, and also because the European BBC TV broadcast was in mono. The US MTV broadcast, the ABC Radio Network and BBC Radio 1 simulcasts were stereo. These recordings circulated among collectors, and in recent years, have also appeared on the Internet in file sharing networks.

Since the official DVD release of Live Aid includes only partial footage of this event, unofficial distribution sources continue to be the only source of the most complete recordings of this event. The official DVD is the only authorised video release in which proceeds go directly to famine relief, the cause that the concert was originally intended to help.

Legacy[]

"Everyone has a common experience of it, everyone remembers where they were and what they felt about it. It’s one of those little pegs that you hang all your other memories on."

—Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling speaking on the BBC's Live Aid – Rockin' All Over the World in 2005.[119]

Live Aid eventually raised $127 million in famine relief for African nations, and the publicity it generated encouraged Western nations to make available enough surplus grain to end the immediate hunger crisis in Africa.[120] According to one aid worker, a larger impact than the money raised for the Ethiopian famine is that "humanitarian concern is now at the centre of foreign policy" for the west.[5]

Regarding Buerk’s landmark BBC News report as a watershed moment in crisis reporting that influenced modern coverage—one that was broadcast in its entirety with Buerk’s narration on a major US channel—Suzanne Franks in The Guardian states, "the nexus of politics, media and aid are influenced by the coverage of a famine 30 years ago."[15]

Many artists and performers at Live Aid gained prominence and positive commercial influence. For all the cultural, charitable, and technological significance of 1985's Live Aid, its most immediate impact was on the charts. In the UK, for example, No Jacket Required by Phil Collins and Madonna's Like a Virgin leapt back into the top ten. Queen's three-year old Greatest Hits rose fifty-five places into the top twenty, followed by Freddie Mercury's Mr. Bad Guy. Every U2 album available at the time also returned to the chart.[121] In 1986, Geldof received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II for his efforts.[120] Claire Bertschinger, the nurse who featured in Buerk’s news reports that sparked the aid relief movement, received the Florence Nightingale Medal in 1991 for her work in nursing, and was made a Dame by Queen Elizabeth II in 2010 for "services to Nursing and to International Humanitarian Aid".[122]

Queen's performance at Live Aid was recreated in the band's 2018 biographical film Bohemian Rhapsody.[123] Footage from the 1985 performance can be seen to match with the movie performance.[123] In February 2020, Queen + Adam Lambert reprised the original Queen setlist from Live Aid for the Fire Fight Australia charity concert in Sydney, Australia.[124]

The background to the staging of the concert as a whole was dramatised in the 2010 television drama When Harvey Met Bob.[125]

See also[]

- 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia

- Band Aid

- Farm Aid, a Live Aid-inspired relief event for American farms, instigated by Bob Dylan

- Live 8, Geldof's 2005 series of concerts aimed at increasing poverty awareness

- Hear 'n Aid, similar joint effort from the heavy metal scene of the 1980s

- List of historic rock festivals

- Self Aid, a 1986 Live Aid-inspired concert highlighting severe unemployment in Ireland, promoted by Jim Aiken

- Sport Aid, another famine relief event organised by Geldof

- Together at Home

- When Harvey Met Bob, a 2010 television film dramatising the events leading up to and including the concert

- Venezuela Aid Live

- YU Rock Misija (YU Rock Mission), Yugoslav contribution to Band Aid campaign

References[]

- ^ Live Aid on Bob Geldof's official site Archived 5 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Billboard Boxscore". Billboard. 27 July 1985. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Live Aid 1985: A day of magic. CNN. Retrieved 22 May 2011

- ^ World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision Archived 19 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Cruel to be kind?". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ "Live Aid index: Bob Geldof". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ "Margaret Thatcher demanded UK find ways to 'destabilise' Ethiopian regime in power during 1984 famine". The Independent. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Live Aid: The Terrible Truth". Spin. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BBC apologises over Band Aid money reports". BBC. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ethiopia famine relief aid: misinterpreted allegations out of control". Barder.com. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Live Aid: The show that rocked the world". BBC. Retrieved 15 September 2011

- ^ "Higgins marvels at change in Ethiopia's Tigray province". The Irish Times. 7 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The nurse who inspired Live Aid". BBC. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Live Aid: Against All Odds: Episode 1". BBC. 7 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ethiopian famine: how landmark BBC report influenced modern coverage". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ The 20th anniversary of Band Aid BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2011

- ^ Billboard 8 Dec 1984 Billboard. Retrieved 15 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Band Aid ... On Stage". Melody Maker. London, England. 12 January 1985. p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Live aid in their own words". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Bob Geldof, Harvey Goldsmith – and the truth about Live Aid". The Telegraph. 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c West, Aaron J. (2015). Sting and The Police: Walking in Their Footsteps. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 92.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Watch David Bowie's iconic performance of 'Heroes' at 'Live Aid' in 1985". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Detailed list of all the artist having performed at the Live Aid concert". Live Aid. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "The Beatles – Let It Be Lyrics". Spin. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "How Phil Collins Became Live Aid's Transcontinental MVP". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Billy Joel 1985 Interview part 2 of 2, retrieved 4 October 2019

- ^ Ellen, Mark (2014). Rock Stars Stole my Life!: A Big Bad Love Affair with Music. Hachette UK.

- ^ "Lessons learned since Live Aid: the challenge of bringing high quality audio to live television audiences continues to change. Kevin Hilton considers how technology has moved on in the 20 years since Live Aid". AllBusiness.com. 1 March 2005. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Hillmore, Peter (1985). Live Aid: the greatest show on earth. p. 60. Sidgwick & Jackson.

- ^ Ling, Dave (January 2002). "Again again again ...". Classic Rock #36. p. 73.

- ^ Hann, Michael (31 March 2014). "Status Quo: Britain's most underrated rock band". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "LIVE AID 1985: Memories of that famous day". BBC. Retrieved 22 May 2011

- ^ "Queen win greatest live gig poll". BBC News. 9 November 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McKee, Briony (13 July 2015). "30 fun facts for the 30th birthday of Live Aid". Digital Spy. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Minchin, Ryan, dir. (2005) "The World's Greatest Gigs". Initial Film & Television. Retrieved 21 May 2011

- ^ Beaumont, Mark. "Aaaaaay-o! Aaaaaay-o! Why Live Aid was the greatest show of all". The Independent. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Holly (6 November 2018). "33 years later, Queen's Live Aid performance is still pure magic". CNN. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Flashback: Queen Steal the Show at Live Aid". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Queen: Live Aid". Ultimate Queen. Retrieved 21 May 2011

- ^ Paphides, Pete (12 June 2011). "U2 become stars after Live Aid". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Edwards, Gavin (10 July 2014). "U2's 'Bad' Break: 12 Minutes at Live Aid That Made the Band's Career". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Greene, Andy (26 January 2016). "Flashback: David Bowie Triumphs at Live Aid in 1985". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "The Story Behind The Song: Sultans Of Swing by Dire Straits". Louder Sound. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Wilkerson, Mark (2006) Amazing Journey: The Life of Pete Townshend p.408. Retrieved 22 May 2011

- ^ "Live Aid – The Global Jukebox Plugs In & Lineup Times". This Day in Music. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "George Michael: 20 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. 7 January 2018.

- ^ Live Aid Galleries The Guardian (London). Retrieved 22 May 2011

- ^ "Geldof, Townshend and McCartney". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 22 May 2011

- ^ "How Bob Geldof's 1985 Live Aid concert changed celebrity fundraising forever". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Studio Sound and Broadcast Engineering – Live aid, Loudspeakers and Monitor" (PDF). American Radio History. 1985. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Studio Sound and Broadcast Engineering – Digital in Audio mixing Consoles" (PDF). American Radio History. 1985. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Live Aid: Jack Nicholson & Joan Baez [1985]. pukenshette. Retrieved 22 November 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Five Things Madonna Should Avoid For A Successful Super Bowl". Houston Press. 6 December 2011.

- ^ Memorable quotes for Live Aid IMDb. Retrieved 21 May 2011

- ^ "When Mick Jagger and Tina Turner Performed Together at Live Aid". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Collins recalls Led Zep 'disaster'". Classic Rock.

- ^ Piner, Mary-Louise. "Return to Stage a Personal Triumph for Teddy Pendergrass". disability-marketing.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones, Dylan (26 July 2010). The Eighties: One Day, One Decade. Random House. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-4090-5225-8.

The [Duran] Duran set was memorable for Simon Le Bon's off-key falsetto note that he hit during 'A View to a Kill', a blunder that echoed throughout the media as 'The Bum Note Heard Round the World'. The singer later said it was the most embarrassing moment of his career.

- ^ "10 Live Aid acts we'll never forget". Readers Digest. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Geldof, Bob. Live Aid DVD.

- ^ Fred Krüger (2015). "Cultures and Disasters: Understanding Cultural Framings in Disaster Risk Reduction". p. 190. Routledge

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (4 July 2005). "Berated by Madonna, rocked by Robbie, stunned into silence by images of famine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Sharp, Keith (2014). Music Express: The Rise, Fall & Resurrection of Canada's Music Magazine. Dundurn Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1459721951.

- ^ "28 Years of Amazing Concerts". Farm Aid website. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Geldof, Bob (1986) Is That It? p.390. Sidgwick & Jackson.

- ^ Daniel Durchholz, Gary Graff (6 May 2010). Neil Young: Long May You Run. Voyageur Press, 2010. p. 134. ISBN 9781610604536. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Past Concerts – Farm Aid". Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Farm Aid 1985 – Champaign, IL". The Concert Stage. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris, Will (25 February 2008). "Eric Bazilian interview". Popdose.com. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Adam Ant brands Live Aid a "mistake" and a "waste of time" and the end of 'rock n roll'". Louder Than War. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Geldof, Bob (1986). Is That It?. London: Penguin Books. p. 333. ISBN 9780330442923.

- ^ Kershaw, Andy (2014). No Off Switch. Buster Press. p. 192-193. ISBN 978-0992769604.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Deriso, Nick (2 November 2014). "Phil Collins Considered Walking Out of Led Zeppelin's Live Aid Reunion". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Williamson, Nigel (2007). The Rough Guide to Led Zeppelin. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-841-7.

- ^ Mark Beaumont (11 July 2020). "Aaaaaay-o! Aaaaaay-o! Why Live Aid was the greatest show of all". The Independent. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Zeppelin defend Live Aid opt out". BBC News. 4 August 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Fiorillo, Victor (15 June 2012). "The 10 Most Painful Band Reunions". Philadelphia. Philadelphia. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Live Aid: The Terrible Truth". Spin.

- ^ "Live Aid: Bob Geldof's Original Response to SPIN's 1986 Exposé". Spin.

- ^ "BBC - The Editors: Bob, Band Aid and how the rebels bought their arms". web.archive.org. 1 October 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Use of funds generated by Live Aid Band Aid Complaint". BBC News. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ O'Reilly, Bill (14 June 2005). "Sharing the Wealth". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Rieff, David (24 June 2005). "Did Live Aid do more harm than good?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Transcript for June 26 – Meet the Press". NBC News. 26 June 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Jones, Dylan (6 June 2013). The Eighties: One Day, One Decade. Random House. p. 150-151. ISBN 978-1-4090-5225-8.

- ^ Kent, Lucinda (13 July 2015). "Live Aid 30th anniversary: Seven things you may not know about Bob Geldof's charity concert". ABC Online. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Michael Jackson Project Kept Him from Concert". The New York Times. 17 July 1985. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mick (28 July 2016). Prince: Purple Reign. Hachette UK. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4091-6923-9.

- ^ Lizie, Arthur (15 June 2020). Prince FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Purple Reign. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-4930-5143-4.

- ^ Goldberg, Michael (16 August 1985). "Live Aid 1985: The Day the World Rocked". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ McKee, Briony (13 July 2015). "30 fun facts for the 30th birthday of Live Aid". Digital Spy. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Live Aid F.A.Q". Liveaid.free.fr. 13 July 1985. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Early Stages sleeve notes 5". Fish—TheCompany.Com Official Site. September 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Chalmers, Graham (15 May 2014). "Interview: Ali's battle for heart and soul of UB40". The North Yorkshire News. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Kadzielawa, Mark. "Thin Lizzy". 69 Faces of Rock. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Peart, Neil (25 April 1988). "All Fired Up". Metal Hammer (Interview). Interviewed by Malcolm Dome. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Turner, Steve: "Roger Waters: The Wall in Berlin"; Radio Times, 25 May 1990; reprinted in Classic Rock No. 148, August 2010, p. 81

- ^ "Live Aid 30th anniversary: 30 things you never knew about the 1985 concert". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (27 August 2004). "How Live Aid was saved for history". BBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Live Aid DVD Launch". Brianmay.com. 8 November 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Live Aid DVD – Premiere at European Cinemas in DTS Surround Sound; Exclusive Cinema Screenings of the Landmark 1985 Concert Recording Played in 5.1 DTS Digital Surround, 12 November 2004

- ^ 20 Years Ago Today – July 2005

- ^ Youngs, Ian (3 March 2004). "Geldof thwarts 'Live Aid pirate'". BBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Zeppelin defend Live Aid opt out". BBC News. 4 August 2004. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Official Music Video Chart Top 50 – 14 November 2004 – 20 November 2004

- ^ Dutch Music DVDs Chart – Week commencing 27 November 2004

- ^ Promusicae Music DVDs Chart – Lista de los titulos mas vendidos del 08.11.04 al 14.11.04

- ^ Music Video Sales – as compiled by Nielsen... 4 December 2004

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations �� 2005 DVDs" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Austrian video certifications – Diverse – Live Aid (DVD)" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- ^ "Canadian video certifications – Various Artists – Live Aid". Music Canada.

- ^ "French video certifications – COMPILATION – LIVE 8" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Diverse Interpreten; 'Live Aid')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ "British video certifications – VARIOUS ARTISTS – LIVE AID". British Phonographic Industry.Select videos in the Format field. Select Platinum in the Certification field. Type LIVE AID in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "American video certifications – VARIOUS – LIVE AID". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ Live Aid (Live, 13 July 1985) | Various artists | 7 September 2018

- ^ Official Live Aid channel – YouTube

- ^ "Stages set for Live 8". Reuters. 2 July 2005. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Live Aid – Rockin' All Over The World". BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Live Aid concert – Jul 13, 1985". History.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Macdonald, Bruno (2010). Six Degrees of Rock Connections: The Complete Road Map of Rock 'N' Roll. Sweet Water Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-1532-510373.

- ^ "No. 59282". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2009. p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sandwell, Ian (23 October 2018). "How Bohemian Rhapsody recreated that incredible Queen performance at Live Aid". Digital Spy. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Dye, Josh (16 February 2020). "Queen reprises famous 1985 Live Aid set at Fire Fight Australia concert". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "When Harvey Met Bob". BBC. 31 December 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

Bibliography[]

- Davis, H. Louise. "Feeding the world a line?: Celebrity activism and ethical consumer practices from Live Aid to Product Red." Nordic Journal of English Studies 9.3 (2010): 89–118.

- Westley, Frances. "Bob Geldof and Live Aid: the affective side of global social innovation." Human Relations 44.10 (1991): 1011–1036.

- Live Aid: Rockin' All Over the World – BBC2 documentary, recalling the build-up to the day, and the day itself; viewed 18 June 2005.

- Live Aid: World Wide Concert Book – Peter Hillmore with Introduction by Bob Geldof, ISBN 0-88101-024-3, Copyright 1985, The Unicorn Publishing House, New Jersey.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Live Aid 1985. |

- BBC news stories about the Live Aid DVD

- Twenty-Five Years on...memories from Herald UK

- How Live Aid was saved for history: BBC News

- Geldof thwarts 'Live Aid pirate': BBC News

- Philly.com: Live Aid Philadelphia Photo Gallery

- In-depth interview between Hal Uplinger, producer of the "Live Aid Concert", the United States event, and the National Museum of American History (part of the Smithsonian Institution)

- Full set list, including Philadelphia – JFK Stadium

- Music festivals established in 1985

- Pop music festivals

- Musical advocacy groups

- Development charities based in the United Kingdom

- Benefit concerts

- 1985 in music

- 1985 in London

- 1985 in Pennsylvania

- 1985 television specials

- British popular music

- British music history

- History of the London Borough of Brent

- Concerts at Wembley Stadium

- Culture of Philadelphia

- History of Philadelphia

- American popular music

- American music history

- Rock festivals

- Simulcasts

- American Broadcasting Company television specials

- MTV original programming

- BBC Television shows

- ABC radio programs

- BBC Radio 1

- Orbis Communications

- Live 8

- 1985 music festivals

- 1985 in economics

- July 1985 events in the United States

- July 1985 events in the United Kingdom

- Benefit concerts in the United Kingdom

- Benefit concerts in the United States