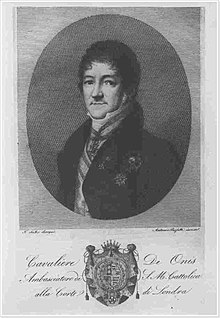

Luis de Onís

Luis de Onís y González-Vara | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Spain to the United States | |

| In office 7 October 1809 – 10 May 1819 | |

| Preceded by | Valentin de Foronda |

| Succeeded by | Francisco Dionisio Vives |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 4, 1762 Cantalapiedra, Salamanca, Spain |

| Died | May 17, 1827 (aged 64) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Spouse(s) | Federika Christina von Mercklein |

| Profession | Diplomat and ambassador of Spain |

Luis de Onís y González-Vara (June 4, 1762 – May 17, 1827) was a career Spanish diplomat who served as Spanish Envoy to the United States from 1809 to 1819,[1] and is remembered for negotiating the cession of Florida to the US in the Adams–Onís Treaty with United States Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, in 1819.[2]

Biography[]

Family and early life[]

Luis de Onís was born in Cantalapiedra, Salamanca on 30 June 1762.[3] He was the son of Joaquin de Onís, a landowner who was probably of noble Asturian origin.[4] Luis received a classical education at home; he began the study of Greek and Latin when he was 8, and by 16, he had concluded his studies in the humanities and law at the University of Salamanca.[5]

Early work as an ambassador[]

In 1780, Onís joined his uncle, José de Onís, ambassador of Spain to the Electorate of Saxony in Dresden, Germany, who was known as one of the most accomplished men in politics, science, and belles lettres of the time. Luis joined the legation as his personal secretary and assumed duties as a trade commissioner. In the course of his work, he visited the royal courts of Berlin and Vienna as well as the courts of the other capital cities in Central Europe.

In 1786, when he was 24 years old, Onís was sent on an important mission by the Spanish government, which knew that Saxony had the most highly developed mining industry in Europe and desired to acquire experienced miners to send to its American colonies. He went to study at the School of Mines in Freiberg, a town dominated by the mining and smelting industries, and enrolled in a course taught by the Prussian mineralogist, Professor Abraham Gottlob Werner.[6] Becoming acquainted with operations in the mines, Onís learned of the existence of a surplus of miners looking for employment. Subsequently, the Count of Floridablanca decided to entrust the mission to the young man. He met with a diplomatic minister of Saxony, who was prepared to reject his request, but he was so impressed by the young man's knowledge of the pertinent facts and the force of his arguments that he agreed to his request and allowed him to choose thirty-six miners, including six managers, to send to Spain. In recognition of Onis's success, the Count proposed to appoint him as a minister to the United States, a promotion that he could not then accept.[7]

In 1792, Onís was decorated with the Cross of Charles III of Spain (Cruz de Carlos III).[8][9] In 1798, he returned to Spain, where he was appointed to a position in the office of the First Secretary of State (Primer Secretarío de Estado) in Madrid, being responsible for conducting negotiations with France. In April 1802, he took an active part in the negotiations for and the conclusion of the Treaty of Amiens[10][11] and, in October, he was granted the customary perks of a "secretary to the King" (secretario del rey), including a house and an expense account.[12]

Following Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Spain in 1808 and with the impending abdication of Ferdinand VII, the remnant of the royal government moved to Seville,[13] where Onís continued in his capacity as longest-serving senior officer of the Ministry.[14] He soon received a proposal to lead a diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg,[15] and then a designation to Sweden, neither of which came to pass. Finally, the Junta Central (the anti-French Spanish Government fighting Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte, now king of Spain as José I), decided to send him to the United States.[16]

Ambassador to the United States[]

On 29 June 1809,[17][18][19] Onís was appointed minister plenipotentiary (with full powers to take independent action) to the United States, his letter of appointment instructing him to embark as soon as possible for New York.[20] His assignment was to ensure peace between the two nations and win formal recognition of Fernando VII as the legitimate ruler of Spain. He was to negotiate all points in dispute within certain defined limits; to encourage the loyalty of Spain's colonies in the New World; to buy supplies, armaments, and ships for Spain to use in its war against the French; and to counter Bonapartist propaganda in the US.[21] He was to pursue these objectives despite the refusal of President James Madison to recognize him while the Peninsular war still raged in Europe.[22] Arriving at the port of New York on 4 October 1809 aboard the Spanish frigate Cornelia, after a rough passage of 44 days, Onís requested an audience to present his credentials to President Madison but was promptly informed that the US government could not receive or recognize any minister from the provisional governments of Spain as long as the crown was in dispute and that until that question was resolved, the United States would remain neutral.

Consequently, no member of the Cabinet would recognize him or enter into any official communication with him.[23] The United States did not officially recognize Onís as ambassador until December 1815, all the while asserting that political considerations obliged it to remain neutral until the conclusion of the war in Spain[24] despite assurances of support for the cause of Spanish independence by Madison.

Soon after his arrival in the United States, Onís took up residence in Philadelphia, where he used the officially recognized consular office to run a shadow legation[25] and worked tirelessly against attempts by the United States to penetrate into Florida,[26] as well as its covert support for French agents moving to infiltrate the Spanish provinces.[27] He paid special attention to the activities of Spanish and Latin American revolutionary agents, who sought to exploit the sympathy that American citizens felt for Spain's rebelling colonies in South America.[28] Secretary of State James Monroe rejected his written protests but clandestinely lent his support to insurgent movements led by filibusterers[29] and irregular American forces.[30] The occupation of West Florida in 1810 was the culmination of a prolonged series of events over the course of several years,[31] as a consequence of the indeterminacy of the border between Florida and Louisiana Purchase when France ceded it to Spain in 1763. At the start of the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain, the danger of invasion of East Florida, a territory that had never been in dispute, escalated and was a constant subject of concern in Onís's correspondence with Monroe. The US government finally officially recognized Onís as Ambassador of Spain, and he presented his credentials on December 20, 1815, five years after his arrival in New York.[5] Thereafter, he continued asserting the Spanish arguments with his customary vigor.

Monroe, meanwhile, sent an ambassador to Madrid, John Erving,[32] who was snubbed by the Spanish Secretary of State, Pedro Cevallos, and had to wait several months for formal recognition of Onís's ambassadorship to the United States.[33] Cevallos opposed making any significant concessions to secure a treaty and endeavored to buy more time for Spain with the mere appearance of negotiations. Cevallos transferred consultations from Madrid to Washington and ensured further delays by sending Onís the necessary powers but no instructions to proceed.[32] Resisting American pressure to begin negotiations in earnest, Onís tried to delay official recognition by Madrid of the US embassy through various subterfuges, such as maneuvering for the replacement of Cevallos, which occurred on 30 October 1816.[34]

During his years in the United States, Onís published several pamphlets critical of its government under the pseudonym "Verus" (Latin: "True").[35] He advised the Viceroy of New Spain (Mexico), Francisco Javier Venegas, and the Governor of Cuba, the Marqués de Someruelos, of the expansionist ambitions of the growing young nation.[27][36] During the Mexican War of Independence, he maintained a network of spies[25] to prevent contact between the rebels and potential allies in the United States. The network was particularly active in the fight against the so-called "insurgent corsairs," many of them French privateers, who placed themselves at the service of the nascent republics of Spanish America.[37]

Adams–Onís treaty[]

The Adams–Onís treaty was signed on 22 February 1819[38] after two years of difficult negotiations and the intervention of the French ambassador Hyde de Neuville, who defended the Spanish position against the radicalism of Henry Clay in the United States Congress, and General Andrew Jackson, who was notoriously hostile to the Spanish presence in East Florida.

Ratification of the treaty had been postponed for two years since Spain wanted to use it as an incentive to keep the United States from lending diplomatic support to the revolutionaries in South America. As soon as the treaty was signed, the US Senate ratified it unanimously; but because of Spain's stalling, a new ratification was necessary and this time there were objections. Clay and other western spokesmen demanded that Spain also give up Texas, but that proposal was defeated by the Senate, which ratified the treaty a second time on 19 February 1821, following ratification by Spain on 24 October 1820. Ratifications were exchanged three days later and the treaty was proclaimed on 22 February 1821, two years after its signing.[39][40]

The treaty consisted of 16 articles,[41] half of which settled issues that had been in dispute since 1783, ceding all the lands of the Spanish Crown located east of the Mississippi, known as the Floridas, to the United States. Settling the most serious point of contention, determining the borders to the west and northwest of the Mississippi, was delayed until the last moment,[42] as Onís aimed at all costs to keep Texas, New Mexico and California under the dominion of Spain.

The signing of the treaty received a surprisingly favorable response from the public[43][44] and the United States Senate. Onís returned to Europe, convinced that the alternative to signing the treaty would have been the loss of all Spanish territories as far west as the boundaries of the Rio Grande[18] and parts of the interior provinces (Provincias Internas) of New Spain.

The Adams–Onís Treaty closed the first era of United States expansion by providing for the cession of East Florida; the abandonment of the controversy over West Florida (a portion of which had been seized by the United States); and the delineating of a boundary with the Spanish province of Mexico that clearly made Spanish Texas a part of Mexico, thus ending much of the vagueness in the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.[45] Spain also ceded, to the US, its claims to the Oregon Country. For Spain, it meant that it kept Texas and retained a buffer zone between its Californian and New Mexican possessions and the territories of the United States.[46]

In 1820 Onís published a 152-page memoir on the diplomatic negotiation. It was translated from Spanish to English by US diplomatic commission secretary, Tobias Watkins, and republished in 1821 in the US.[47]

Honors and last years[]

In 1818, the Spanish Cortes conferred on Onís the title of Regidor perpetuo de Salamanca (Perpetual alderman of Salamanca), a title that passed to his descendants in the male line.[48] In mid-1819, Onís was awarded the Gran Cruz Americana (American Grand Cross) and the honors of Consejero de Estado (Councilor of State) and was appointed minister to St. Petersburg. The revolution of 1820, however,[49] prevented his assuming this office. The new constitutional government revoked the appointment and instead assigned him to the embassy in Naples.[9][50] The same year, he published a work in two volumes, entitled Memoria sobre las Negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América (Memoir Upon the Negotiations between Spain and the United States of America),[51] a memoir of his role in the negotiations leading to the Treaty of 1819. His last diplomatic mission sent him to London in February 1821, where he participated in diplomatic consultations for the recognition of Hispanic American countries by the United States and managed to prevent the European powers from following the US example. In November 1822, Onís returned to Madrid,[52] where he died on 17 May 1827,[53][54] after an illness of four days.

Personal life[]

Luis married Federika Christina von Mercklein in Dresden[55] on 9 August 1788. They had three children: Mauricio, Narciss, and Clementina.

References[]

- ^ Luis de Onís. "Luis de Onís to Thomas Jefferson, 17 October 1809". Founders Online ~ National Archives. Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (2012). The Encyclopedia of the War of 1812: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 955. ISBN 978-1-85109-957-3.

- ^ Pablo Beltrán de Heredia y Onís (1986). Los Onís, una secular familia salmantina. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. p. 49.

- ^ Ángel del Río (1981). La misión de don Luis de Onís en los Estados Unidos (1809–1819). S.l. p. 39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jon Kukla (2009). A Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 516. ISBN 978-0-307-49323-1.

- ^ Boletín de historia y antigüedades. Imprenta Nacional. 1953. pp. 323–324.

- ^ Manuel Ortuño (2001). "Onís y González, Luis de (1762–1827)". Mcnbiografias.com (in Spanish). Micronet. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012.

- ^ United States. Congress. House (1872). House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session. p. 221.

- ^ Jump up to: a b José García de León y Pizarro (1897). Memorias de la Vida. Est. Tipográfico. Sucessores de Rivadeneyra. p. 364.

- ^ Manuel Fernández de Velasco (1965). Las relaciones diplomáticas entre España y los Estados Unidos: don Luis de Onís y el tratado transcontinental de la Florida, 1809–1819. Universidad Nacional Autónoma. F. de F. y L. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Carl Cavanagh Hodge (2008). Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1914. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 872. ISBN 978-0-313-04341-3.

- ^ Manuel Fernández de Velasco (1982). Relaciones España-Estados Unidos y mutilaciones territoriales en Latinoamérica. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. p. 62. ISBN 978-968-5803-54-0.

- ^ Robert V. Baer (2008). Power & Freedom: Political Thought and Constitutional Politics in the United States and Argentina. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-549-74510-5.

- ^ Manuel Moreno Alonso (1 January 2010). El Nacimiento de una Nación: Sevilla, 1808–1810: La Capital de una Nación en Guerra. Ediciones Cátedra, S.A. p. 284. ISBN 978-84-376-2652-9.

- ^ Pablo Beltrán de Heredia y Onís (1986). Los Onís, una secular familia salmantina. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. p. 35.

- ^ Manuel Fernández de Velasco (1965). Las relaciones diplomáticas entre España y los Estados Unidos: don Luis de Onís y el tratado transcontinental de la Florida, 1809–1819. Univ. Nac. Autónoma. F. de F. y L. p. 58.

- ^ Río 1981, p. 44

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cuadernos hispanoamericanos. Ediciones Cultura Hispa(nica. January 1984. p. 179.

- ^ Alberto Romero Ferrer; Fernando Durán López; Yolanda Vallejo Márquez (1995). De la ilustración al romanticismo, 1750–1850: "Juego, fiesta y transgresión" (Cádiz, 16, 17 y 18 de Octubre de 1991) : VI Encuentro. Servisio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Cádiz. p. 447. ISBN 978-84-7786-287-1.

- ^ Leopoldo Stampa (1 January 2011). Pólvora, plata u boleros: memoria de embajadas, saqueos y pasatiempos relatados por testigos combatientes de la Guerra de la Independencia 1808–1814. Marcial Pons Historia. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-84-92820-36-8.

- ^ Salvador Broseta (1 January 2002). Las ciudades y la guerra, 1750–1898. Universitat Jaume I. p. 63. ISBN 978-84-8021-389-9.

- ^ William C. Davis (20 April 2011). The Rogue Republic: How Would-Be Patriots Waged the Shortest Revolution in American History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-547-54915-6.

- ^ Luis de Onís (1821). Memoir Upon the Negotiations Between Spain and the United States of America, which Led to the Treaty of 1819: With a Statistical Notice of that Country. Accompanied with an Appendix, Containing Important Documents for the Better Illustration of the Subject. F. Lucas, Jr. pp. 11–13.

- ^ Andy Doolen (23 May 2014). Territories of Empire: U.S. Writing from the Louisiana Purchase to Mexican Independence. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-19-934863-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b William C. Davis (1 May 2006). The Pirates Laffite: The Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 143. ISBN 0-547-35075-9.

- ^ Alicia Mayer (2007). México en tres momentos, 1810-1910-2010: hacia la conmemoración del bicentenario de la Independencia y del centenario de la Revolución Mexicana : retos y perspectivas. UNAM. p. 98. ISBN 978-970-32-4460-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gordon S. Brown (7 April 2015). Latin American Rebels and the United States, 1806–1822. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4766-2082-4.

- ^ William Earl Weeks (5 February 2015). John Quincy Adams and American Global Empire. University Press of Kentucky. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8131-4837-3.

- ^ Dick Steward (1 December 2000). Frontier Swashbuckler: The Life and Legend of John Smith T. University of Missouri Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8262-6343-8.

- ^ Deborah A. Rosen (6 April 2015). Border Law. Harvard University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-674-42571-2.

- ^ Clement Anselm Evans (1899). Curry, J. L. M.; Legal justification of the South in secession. Garrett, W.R.; The South as a factor in the territorial expansion of the United States. Evans, C. A.; The Civil history of the Confederate States. Confederate Publishing Company. pp. 171–172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b James E. Lewis Jr. (9 November 2000). The American Union and the Problem of Neighborhood: The United States and the Collapse of the Spanish Empire, 1783–1829. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8078-6689-4.

- ^ Mid-America: An Historical Review. Loyola University Institute of Jesuit History. 1963. p. 68.

- ^ Timothy E. Anna (1983). Spain & the loss of America. University of Nebraska Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8032-1014-1.

- ^ Luis de Onís (1820). Memoria sobre las negociaciones entre España y los Estados-Unidos de América, que dieron motivo al tratado de 1819, con una noticia sobre la estadistica de aquel pais. Acompaña un Apéndice, etc. p. 24.

- ^ Ed Bradley (10 February 2015). We Never Retreat. Texas A&M University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-62349-257-1.

- ^ Gwendolyn Midlo Hall (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-8071-1999-0.

- ^ Florida; James Ernest Calkins (1920). The Revised General Statutes of Florida: Prepared Under Authority of Chapter 6930, Acts 1915, Chapter 7347, Acts 1917, and Chapter 7838, Acts 1919, Laws of Florida. Adopted by the Legislature of the State of Florida, June 9, 1919. James E. Calkins, Commissioner. E. O. Painter printing Company. p. 243.

- ^ Barbara A. Tenenbaum; Georgette M. Dorn (1996). Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture: Abad to Casa. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-684-19752-4.

- ^ Bradley 2015, p. 225

- ^ "Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015.

- ^ J. C. A. Stagg (1 January 2009). Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish-American Frontier, 1776–1821. Yale University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-300-15328-6.

- ^ Edward W. Chester (1975). Sectionalism, Politics, and American Diplomacy. Scarecrow Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8108-0787-7.

Editorial eaction to the Transcontinental Treaty in this country was generally favorable...

- ^ Alvin Laroy Duckett (1 April 2010). John Forsyth: Political Tactician. University of Georgia Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8203-3534-6.

- ^ Alexandra Harmon (15 December 2011). The Power of Promises: Rethinking Indian treaties in the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-295-80046-2.

- ^ Fred Anderson; Andrew Cayton (29 November 2005). The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America, 1500–2000. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-101-11879-5.

- ^ Onís, Luis de (1821) [Originally published in Spanish in 1820 in Madrid, Spain]. Memoir Upon the Negotiations Between Spain and the United States of America, Which Led to the Treaty of 1819. Translated by Watkins, Tobias. Washington, D.C.: E. De Krafft, Printer. p. 3.

- ^ Río 1981, p. 207

- ^ Russell H. Bartley (3 October 2014). Imperial Russia and the Struggle for Latin American Independence, 1808–1828. University of Texas Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-4773-0074-9.

- ^ Antonio Alcalá Galiano; Juan Donoso Cortés; Francisco Martínez de la Rosa (1846). Historia de España: desde los tiempos primitivos hasta la mayoria de la Reina Doña Isabel II. Imp. de la Sociedad Literaria y Tipográfica. p. 121.

- ^ Luis De Onis (1966). Memorias sobre las negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América: or Luis de Onis. Editorial Jus.

- ^ José Pablo Alzina (1 January 2001). Embajadores de España en Londres: Una Guía de Retratos de la Embajada de España. Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores. Area de Documentacion y Publicaciones. p. 11. ISBN 978-84-95265-19-7.

- ^ José Nicolás de Azara (10 December 2011). Epistolario (1784–1804). Parkstone International. p. 1610. ISBN 978-84-9740-464-8.

- ^ Spencer Tucker (2013). The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 475. ISBN 978-1-85109-853-8.

- ^ Emilio Cuenca Ruiz; Margarita del Olmo Ruiz (2014). Padín, Jesús E. (ed.). Masoneria Ritos y Simbolos Funerarios: Mauricio de Onís y el Santo Velo del Sepulcro (PDF). Guadalajara: Guada Book library. p. 105.

Further reading[]

- Brooks, Philip Coolidge. Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams-Onís treaty of 1819 (U of California Press, 1939).

- Hawkins, Timothy. A Great Fear: Luís de Onís and the Shadow War against Napoleon in Spanish America, 1808–1812 (U of Alabama Press, 2019).

- 1769 births

- 1827 deaths

- People from the Province of Salamanca

- University of Salamanca alumni

- Ambassadors of Spain to the United States