M1841 12-pounder howitzer

| M1841 12-pounder howitzer | |

|---|---|

Bronze 12-pounder howitzer at Gettysburg National Military Park | |

| Type | Howitzer |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1841–1868 |

| Used by | |

| Wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Cyrus Alger & Co. N. P. Ames Eagle Foundry, Cincinnati William D. Marshall & Co. |

| Produced | 1841 |

| No. built | over 251 |

| Variants | 1835, 1838 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 785 lb (356.1 kg) |

| Length | 53.0 in (1.35 m) |

| Shell weight | 8.9 lb (4.0 kg) shell 1.0 lb (0.5 kg) charge |

| Caliber | 4.62 in (117 mm) |

| Barrels | 1 |

| Action | Muzzle loading |

| Carriage | 900 lb (408.2 kg) |

| Rate of fire | 1 rounds/minute |

| Effective firing range | 1,072 yd (980 m) |

The M1841 12-pounder howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzle-loading artillery piece that was adopted by the United States Army in 1841 and employed from the Mexican–American War to the American Civil War. It fired a 8.9 lb (4.0 kg) shell up to a distance of 1,072 yd (980 m) at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot and spherical case shot. The howitzer proved effective when employed by light artillery units during the Mexican–American War. The howitzer was used throughout the American Civil War, but it was outclassed by the 12-pounder Napoleon which combined the functions of both field gun and howitzer. In the US Army, the 12-pounder howitzers were replaced as soon as more modern weapons became available. Though none were manufactured after 1862, the weapon was not officially discarded by the US Army until 1868. The Confederate States of America also manufactured and employed the howitzer during the American Civil War. The Confederate armies used the outmoded howitzer for a longer period.

Background[]

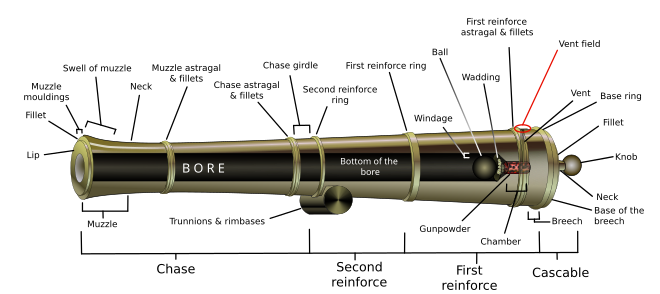

At the beginning of the 19th century, armies employed field guns for direct artillery fire and mortars for high-angle fire. Intermediate between the field gun and mortar was the howitzer which launched an explosive shell on a curved trajectory against enemy personnel or fortifications. In general, a howitzer required a smaller charge than a field gun to lob a projectile of similar weight. Larger howitzers were often named after the size of the bore (or caliber), for example the 8-inch howitzer.[1] On the other hand, by British and American convention, some howitzers were named after the field gun which had the same bore size.[2] Therefore, in the US Army, the weapon was named the 12-pounder howitzer because it had the same bore size as the 12-pounder gun, which was 4.62 in (117 mm) in diameter. Since a smaller charge was needed to fire a projectile, the 12-pounder howitzer had a smaller chamber near the breech 3.67 in (93 mm) in diameter.[1]

Manufacture of bronze artillery pieces required copper and tin. Since the United States had few copper and no known tin deposits, in 1800 Secretary of War Henry Dearborn urged all cannons to be cast from iron. For two decades after the War of 1812 the United States failed to produce a reliable 6-pounder gun. In one lot of 86 cast iron guns, 21 burst at the first fire during testing. Consequently, the Ordnance Board of 1831 under Alexander Macomb specified that field artillery pieces should be manufactured from bronze. The 1834 regulations required that field guns be made in 6-, 9-, and 12-pounder calibers and howitzers in 12- and 24-pounder calibers. It was desired for the 12-pounder howitzer to fit the 6-pounder field gun carriage. After some experimentation, gun founders Cyrus Alger & Co. and N. P. Ames produced the successful bronze smoothbore M1841 6-pounder field gun.[3]

Cyrus Alger and Co. delivered 19 and N. P. Ames delivered seven bronze Model 1835 12-pounder howitzers in 1837–38. The two companies produced more bronze Model 1838 12-pounder howitzers in 1839–40. The Model 1835 was 53.0 in (1.35 m) in length and weighed 717 lb (325.2 kg) while the Model 1838 was 49.0 in (1.24 m) in length and weighed 690 lb (313.0 kg). During the period 1834–1841, Alger, Ames, the West Point Foundry, and the Columbia Foundry produced small numbers of cast iron versions, but no large contracts resulted. The final bronze Model 1841 12-pounder howitzers manufactured by Alger and Ames served the US Army for the next 27 years. The Model 1841 was 53.0 in (1.35 m) long and weighed 785 lb (356.1 kg).[4]

The Eagle Foundry of Miles Greenwood in Cincinnati, Ohio produced 14 bronze M1841 12-pounder howitzers for the US Army in 1861–62. The Western Foundry of William D. Marshall and Co. of St. Louis, Missouri delivered 16 bronze M1841 12-pounder howitzers to the US Army.[5] Several foundries in the Confederacy manufactured an estimated 118 bronze and 66 cast iron 12-pounder howitzers during the American Civil War. Leading all producers was the Tredegar Iron Works which delivered 42 bronze and 30 cast iron 12-pounder howitzers. Other Confederate producers of this weapon were Quinby and Robinson (43), T. M. Brennan (26), Noble Brothers (14), Leeds (9), John Clark (7), Washington Foundry (7), Wolff (3), A. B. Reading (2), and Skates (1).[6]

| Description | No. Accepted | Base ring diameter | Length w/o knob | Bore length | Bore len. in calibers | Weight of barrel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1835 | 26 | 9.8 in (24.9 cm) | 53.0 in (134.6 cm) | 43.25 in (109.9 cm) | 9.36 | 717 lb (325.2 kg) |

| Model 1838 | 24 | 9.8 in (24.9 cm) | 49.0 in (124.5 cm) | 39.25 in (99.7 cm) | 8.5 | 690 lb (313.0 kg) |

| Model 1841 | 251+ | 10.0 in (25.4 cm) | 53.0 in (134.6 cm) | 43.25 in (109.9 cm) | 9.36 | 785 lb (356.1 kg) |

Specifications[]

The Model 1841 bronze 12-pounder howitzer barrel was 53.0 in (134.6 cm) from the base ring to the muzzle and weighed 785 lb (356 kg). The diameter of the bore (caliber) was 4.62 in (11.73 cm) and the bore length was 43.25 in (109.86 cm). This means the bore was 9.36 calibers long. The howitzer fired a 8.9 lb (4.0 kg) shell. At 5° elevation, the gun could throw the shell a distance of 1,072 yd (980 m) with the standard firing charge of 1.0 lb (0.45 kg).[7] Using a 1.0 lb. charge, the howitzer could hurl the shell a distance of 840 yd (768 m) at 3° elevation and 975 yd (892 m) at 4° elevation.[8] Canister shot was effective out to a distance of 350 yd (320 m). The 12-pounder spherical case shot was loaded with 78 musket balls. The 12-pounder canister round contained 27 cast iron balls.[9]

A 6-pounder battery typically included four 6-pounder field guns and two 12-pounder howitzers. Altogether, the battery required 14 6-horse teams and seven spare horses.[10] The teams pulled the six artillery pieces and limbers, six caissons and limbers, one battery wagon, and one traveling forge. Each caisson carried two ammunition chests and each of the two limbers carried one, so that each gun was supplied with four ammunition chests.[11] The Union 1864 Field Artillery Instructions and the Confederate 1863 Ordnance Manual both prescribed that each ammunition chest held 15 shells, 20 spherical case shot, and four canister rounds. The total weights were as follows: shells 157.5 lb (71.4 kg), spherical case 273 lb (123.8 kg), and canister 47.4 lb (21.5 kg).[12] The carriage for both the 6-pounder gun and the 12-pounder howitzer weighed 900 lb (408 kg).[13]

| Description | Dimension |

|---|---|

| Weight of the gun barrel | 785 lb (356.1 kg) |

| Diameter of the bore (caliber) | 4.62 in (11.73 cm) |

| Diameter of the chamber | 3.67 in (9.32 cm) |

| Length of the bore including chamber | 50.5 in (128.3 cm) |

| Length of the chamber | 4.25 in (10.8 cm) |

| Length from the rear of the base ring to the face of the muzzle | 53 in (134.6 cm) |

| Length from the rear of the knob to the face of the muzzle | 58.6 in (148.8 cm) |

| Length from the rear of the base ring to the end of the (second) reinforce | 30 in (76.2 cm) |

| Length of the chase from the end of the reinforce to the rear of the chase ring | 18.4 in (46.7 cm) |

| Length from the rear of the chase ring to the face of the muzzle | 4.6 in (11.7 cm) |

| Length from the rear of the base ring to the rear of the trunnions | 23.25 in (59.1 cm) |

| Diameter of the base ring | 10.0 in (25.4 cm) |

| Thickness of metal at the vent | 2.9 in (7.4 cm) |

| Thickness of metal at the end of the (second) reinforce | 2.09 in (5.3 cm) |

| Thickness of metal at the end of the chase and at the neck | 1.54 in (3.9 cm) |

History[]

Mexican–American War[]

In 1840, Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett sent American officers to Europe to study artillery. This led to the establishment of an artillery system in 1841 where the 6-pounder gun and 12-pounder howitzer were adopted as field artillery. At the start of the Mexican–American War, the US Army maintained four artillery regiments, each with 10 companies of 50 men each. There were only four highly trained light artillery batteries: James Duncan's Company A, 2nd Artillery Regiment, Samuel Ringgold's Company C, 3rd Artillery, Braxton Bragg's Company E, 3rd Artillery, and John M. Washington's Company B, 4th Artillery. The first three were assigned to Zachary Taylor's army at the beginning of the war, while Washington's joined Taylor's army later.[15]

The Battle of Palo Alto on 8 May 1846 was largely an artillery duel in which the American batteries inflicted disproportionate losses on the Mexican soldiers.[16] Though most accounts state that the batteries of Ringgold and Duncan were armed with four 6-pounder guns each, an archeological study found evidence that one or more 12-pounder howitzers were used.[17] American losses were only five killed, 43 wounded, and two missing. However, 10 more soon died of their wounds, including Ringgold who was struck in both legs by a round shot from a 4-pounder Gribeauval cannon. Mexican commander Mariano Arista admitted losing 252 killed, but wrote only 102 killed in his official report. The next morning, the Mexican army fell back to a second position but it was beaten that day at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.[18]

In the Battle of Buena Vista on 22–23 February 1847, Taylor's army counted 4,800 soldiers and the artillery batteries of Thomas W. Sherman (3rd Artillery), Washington, and Bragg. Washington's battery may have had eight field pieces, and the others six. During the action, the numerically superior Mexican army under Antonio López de Santa Anna forced many of the American volunteer units to retreat, but the artillery saved the day. On the morning of 24 February, Santa Ana's army had withdrawn.[19] In the Battle for Mexico City, the 14,000-man American army of Winfield Scott was organized into four divisions with an artillery battery assigned to each division. These were Duncan's Company A (light), 2nd Artillery – William J. Worth's division, Company K (light), 1st Artillery – David E. Twiggs' division, Company I (light), 1st Artillery – Gideon Pillow's division, and Company H, 3rd Artillery – John A. Quitman's division.[20]

American Civil War[]

George B. McClellan was part of the American Military Commission to Europe of 1856 where he observed the new French Canon obusier de 12 which incorporated the functions of both field gun and howitzer. He recognized the superiority of the new cannon – called the Napoleon – over mixed batteries. When McClellan took command of the Federal forces in the summer of 1861, he approved the recommendations of William Farquhar Barry. These included replacing the 20 year old smoothbore cannons with the 12-pounder Napoleon and organizing 6-gun batteries of all the same caliber.[21] After the First Battle of Bull Run on 25 July 1861, the US Army in the east had 650 gunners manning nine batteries of mostly mixed calibers. By March 1862 the Army of the Potomac had 92 batteries of 520 guns manned by 12,500 soldiers and pulled by 11,000 horses.[22]

At the Battle of Pea Ridge on 6–7 March 1862, both armies were equipped with Model 1841-vintage artillery pieces and the weapons were organized in mixed batteries. Nearly all the Union batteries were made up of four smoothbore or rifled 6-pounder field guns and two 12-pounder howitzers. The units were the 2nd Ohio Battery, 4th Ohio Battery, 1st Iowa Independent Battery Light Artillery, 3rd Iowa Independent Battery Light Artillery, 1st Independent Battery Indiana Light Artillery, Battery "A", 2nd Illinois Light Artillery Regiment, and Elbert's 1st Missouri Flying Battery. Welfley's Independent Missouri Battery was armed with four 12-pounder howitzers and two 12-pounder field guns.[23] Many of the Confederate units at Pea Ridge were mixed batteries. Batteries armed with two 12-pounder howitzers were Provence's and Gaines's Arkansas batteries, Landis's, Guibor's, and MacDonald's Missouri batteries and Good's Texas Battery. Wade's Missouri battery had four 12-pounder howitzers and two 6-pounder field guns.[24]

The Battle of Antietam on 17 September 1862 was fought in the eastern theater. At Antietam, there were 44 12-pounder howitzers in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia while the Army of the Potomac employed only three.[25] The Union 8th Massachusetts Light Artillery (Cook's) was armed with two 12-pounder howitzers and four 12-pounder James rifles,[26] while Simmond's Battery Kentucky Light Artillery had one 12-pounder howitzer, two 20-pounder Parrott rifles, and three 10-pounder Parrott rifles. Curiously, the Kentucky unit's howitzer was cast iron and probably a captured piece.[27] The Confederate 4th Battery Washington Artillery (Eshleman's) was armed with two 12-pounder howitzers and two 6-pounder field guns.[28]

The Battle of Gettysburg on 1–3 July 1863 was also fought in the east. At Gettysburg, 64 of 65 Federal batteries were armed with the same weapons; the only mixed battery was Sterling's 2nd Connecticut Light Artillery Battery.[29] Sterling's Battery was armed with four James rifles and two 12-pounder howitzers.[30] Ames and Alger manufactured the last bronze 12-pounder howitzers in 1861–62.[31] Wartime records show that out-of-date artillery pieces migrated from the east to the west in the US Army.[32]

Civil War artillery[]

| Description | Caliber | Tube length | Tube weight | Carriage weight | Shot weight | Charge weight | Range 5° elev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1841 6-pounder cannon | 3.67 in (9.3 cm) | 60 in (152.4 cm) | 884 lb (401 kg) | 900 lb (408 kg) | 6.1 lb (2.8 kg) | 1.25 lb (0.6 kg) | 1,523 yd (1,393 m) |

| M1841 12-pounder cannon | 4.62 in (11.7 cm) | 78 in (198.1 cm) | 1,757 lb (797 kg) | 1,175 lb (533 kg) | 12.3 lb (5.6 kg) | 2.5 lb (1.1 kg) | 1,663 yd (1,521 m) |

| M1841 12-pounder howitzer | 4.62 in (11.7 cm) | 53 in (134.6 cm) | 788 lb (357 kg) | 900 lb (408 kg) | 8.9 lb (4.0 kg) | 1.0 lb (0.5 kg) | 1,072 yd (980 m) |

| M1841 24-pounder howitzer | 5.82 in (14.8 cm) | 65 in (165.1 cm) | 1,318 lb (598 kg) | 1,128 lb (512 kg) | 18.4 lb (8.3 kg) | 2.0 lb (0.9 kg) | 1,322 yd (1,209 m) |

| M1857 12-pounder Napoleon | 4.62 in (11.7 cm) | 66 in (167.6 cm) | 1,227 lb (557 kg) | 1,128 lb (512 kg) | 12.3 lb (5.6 kg) | 2.5 lb (1.1 kg) | 1,619 yd (1,480 m) |

| 12-pounder James rifle | 3.67 in (9.3 cm) | 60 in (152.4 cm) | 875 lb (397 kg) | 900 lb (408 kg)[34] | 12 lb (5.4 kg) | 0.75 lb (0.3 kg) | 1,700 yd (1,554 m) |

| 3-inch Ordnance rifle | 3.0 in (7.6 cm) | 69 in (175.3 cm) | 820 lb (372 kg) | 900 lb (408 kg)[35] | 9.5 lb (4.3 kg) | 1.0 lb (0.5 kg) | 1,830 yd (1,673 m) |

| 10-pounder Parrott rifle | 3.0 in (7.6 cm) | 74 in (188.0 cm) | 899 lb (408 kg) | 900 lb (408 kg)[35] | 9.5 lb (4.3 kg) | 1.0 lb (0.5 kg) | 1,900 yd (1,737 m) |

| 20-pounder Parrott rifle | 3.67 in (9.3 cm) | 84 in (213.4 cm) | 1,750 lb (794 kg) | 1,175 lb (533 kg)[34] | 20 lb (9.1 kg) | 2.0 lb (0.9 kg) | 1,900 yd (1,737 m) |

Notes[]

- ^ a b Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 86.

- ^ a b Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Katcher 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Coggins 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Coggins 1983, p. 73.

- ^ Coggins 1983, p. 68.

- ^ Katcher 2001, p. 18.

- ^ a b Coggins 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Eisenhower 1989, p. 379.

- ^ Eisenhower 1989, p. 79.

- ^ Haecker 1994, Chap.7.

- ^ Haecker 1994, Chap.3.

- ^ Eisenhower 1989, pp. 185–191.

- ^ Eisenhower 1989, p. 307.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Cole 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 331–334.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 334–339.

- ^ Johnson & Anderson 1995, p. 129.

- ^ Johnson & Anderson 1995, p. 77.

- ^ Johnson & Anderson 1995, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Johnson & Anderson 1995, p. 90.

- ^ Cole 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Morgan 2002.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Coggins 1983, p. 77.

- ^ a b Johnson & Anderson 1995, p. 25.

- ^ a b Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks 2004, p. 217.

References[]

- Coggins, Jack (1983). Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. New York, N.Y.: Fairfax Press. ISBN 0-517-402351.

- Cole, Phillip M. (2002). Civil War Artillery at Gettysburg. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81145-6.

- Eisenhower, John (1989). So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico 1846–1848. New York, N.Y.: Random House. ISBN 0-394-56051-5.

- Haecker, Charles M. (1994). "A Thunder of Cannon: Archaeology of the Mexican–American War Battlefield of Palo Alto". Santa Fe, N.M.: National Park Service.

- Hazlett, James C.; Olmstead, Edwin; Parks, M. Hume (2004). Field Artillery Weapons of the American Civil War. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07210-3.

- Johnson, Curt; Anderson, Richard C. Jr. (1995). Artillery Hell: The Employment of Artillery at Antietam. College Station, Tex.: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-623-0.

- Katcher, Philip (2001). American Civil War Artillery 1861–1865. Osceola, Wisc.: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-451-5.

- Morgan, James (2002). "Green Ones and Black Ones: The Most Common Field Pieces of the Civil War". civilwarhome.com.

- Shea, William L.; Hess, Earl J. (1992). Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.

See also[]

- Downey, Brian (2019). "The Weapons of Antietam". Antietam on the Web.

- Ripley, Warren (1984). Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War. Charleston, S.C.: The Battery Press. OCLC 12668104.

- American Civil War artillery