Maccus mac Arailt

| Maccus mac Arailt | |

|---|---|

| King of the Isles | |

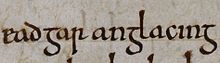

Maccus' name as it appears on page 59r of Oxford Jesus College 111 (the Red Book of Hergest): "Marc uab herald".[1] | |

| Successor | Gofraid mac Arailt |

| Dynasty | Uí Ímair (probably) |

| Father | Aralt mac Sitriuc (probably) |

Maccus mac Arailt (fl. 971–974), or Maccus Haraldsson, was a tenth-century King of the Isles.[note 1] Although his parentage is uncertain, surviving evidence suggests that he was the son of Harald Sigtryggson, also known as Aralt mac Sitriuc, the Hiberno-Norse King of Limerick. Maccus' family is known as the Meic Arailt kindred. He and his brother, Gofraid, are first recorded in the 970s. It was during this decade and the next that they conducted military operations against the Welsh of Anglesey, apparently taking advantage of dynastic strife within the Kingdom of Gwynedd.

The Meic Arailt violence during this period could account for Maccus' participation in a royal assembly convened by Edgar, King of the English. Maccus may have been regarded as a potential threat by not only the English and Welsh kings, but also the rulers of the Kingdom of Strathclyde. Perhaps as a consequence of this convention, the Meic Arailt thereafter turned their attention to Ireland. In 974, Maccus defeated and captured Ímar, King of Limerick. Gofraid resumed the family's campaigning against the Welsh before the end of the decade. In 984, the Meic Arailt appear to have formed an alliance with the family of Brian mac Cennétig, King of Munster. Whether Maccus was alive by this date is unknown. He does not appear on record after this date, and seems to have been succeeded by his brother. Gofraid is the first King of the Isles to be identified as such by Irish sources.

Family[]

Maccus was a member of the Meic Arailt kindred,[11] although his exact parentage is uncertain.[12] Surviving evidence suggests that Maccus' father was probably Aralt mac Sitriuc, King of Limerick.[13] Such a relationship would mean that Maccus was a member of the Uí Ímair.[14] Alternate possibilities—lacking specific evidence—are that Maccus was a son of Hagrold, a Danish warlord active in Normandy;[15] or a son of Haraldr Gormsson, King of Denmark.[16]

Maccus appears to have been an elder[17] brother of Gofraid mac Arailt.[18] A sister of Maccus and Gofraid,[19] or perhaps a daughter of the latter, may have been Máel Muire, wife of Gilla Pátraic mac Donnchada, King of Osraige.[20] Specific evidence of a familial relationship between Máel Muire and the Meic Arailt may be preserved by the twelfth-century Banshenchas, a source that identifies the mother of Gilla Pátraic's son, Donnchad, as Máel Muire, daughter of a certain Aralt mac Gofraid. One possibility is that this source has erroneously reversed the patronym of Maccus' brother.[21] Another brother of Maccus may have been Eiríkr Haraldsson, a Viking who ruled the Kingdom of Northumbria in the mid part of the tenth century.[22] Although non-contemporary Scandinavian sources identify this figure with the like-named Norwegian royal Eiríkr blóðøx, there is reason to suspect that these sources have erroneously conflated two different individuals,[23] and that the former was a member of the insular Uí Ímair.[24]

There is uncertainty surrounding Maccus' name.[26] Although the nineteenth-century edition of the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters refers to him as Maghnus mac Arailt, suggesting that the Gaelic Maccus is a form of the Old Norse Magnús[27]—itself a borrowing of the Latin Magnus[28]—the oldest manuscript forms of this source show that the recorded name was actually an abbreviated form of Maccus.[27] Besides this mistranscription, Maccus is not accorded the name Magnus by any historical source,[29] and his name is unlikely to refer to it.[30] Maccus' name may instead be of Gaelic origin.[31][note 2]

Irruption into the Irish Sea region[]

The Meic Arailt first appear on record in the Irish Sea in the 970s.[36] The power of the family seems to have been centred in the Isles,[37] and may have been based upon control of the important trade routes through the Irish Sea region.[38] If the Meic Arailt were indeed centred in the Hebrides, the family's apparent ambition to secure control of Mann could account for its campaigning against the Welsh on Anglesey.[39] The latter island was the traditional seat of the kings of Gwynedd,[40] and control of it may have been sought by the Meic Arailt as a way to further ensure the control of the surrounding sea-lanes.[41]

According to the "B" version of the eleventh- to thirteenth-century Annales Cambriæ, an unidentified son of Aralt wasted this island off the north-west Welsh coast.[42] The thirteenth- and fourteenth-century texts Brut y Tywysogyon[43] and Brenhinedd y Saesson corroborate this record and identify the attacker as Maccus himself.[44][note 3] Maccus' assault targeted Penmon on the eastern coast of the island.[46] Several near-contemporary engraved crosses at Penmon indicate that it was a significant ecclesiastical site with important patrons.[34] Both Brut y Tywysogyon[47] and Brenhinedd y Saesson further reveal that Gofraid attacked Anglesey the next year, and thereby brought the island under his control.[48][note 4] At the time of the Meic Arailt kindred's attacks, the Kingdom of Gwynedd was in the midst of a vicious civil war triggered by the death of Rhodri ab Idwal Foel, King of Gwynedd in 969, a fact which could indicate that the Meic Arailt purposely sought to capitalise on this infighting.[50]

Amongst an assembly of kings[]

There is evidence indicating that Maccus was amongst the assembled kings who are recorded to have met with Edgar, King of the English at Chester in 973.[52] According to the "D", "E", and "F" versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, after having been consecrated king that year, this English monarch assembled a massive naval force and met with six kings at Chester.[53] By the tenth century, the number of kings who met with him was alleged to have been eight, as evidenced by the tenth-century Life of St Swithun.[54][note 5] By the twelfth century, the eight kings began to be named and were alleged to have rowed Edgar down the River Dee, as evidenced by sources such as the twelfth-century texts Chronicon ex chronicis,[56] Gesta regum Anglorum,[57] and De primo Saxonum adventu,[58] as well as the thirteenth-century Chronica majora,[59] and both the Wendover[60] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum.[61]

Whilst one of the named kings appears to have been Maccus himself,[52] a certain other—named Siferth by Gesta regum Anglorum, and Giferth by Chronicon ex chronicis—could have been Gofraid.[63] Gesta regum Anglorum describes Maccus as archipirata ("prince of the pirates" or "pirate king"),[64] whilst Chronicon ex chronicis,[65] De primo Saxonum adventu,[66] and the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Melrose (which also notes the assembly) call him plurimarum rex insularum ("king of many islands" or "king of very many islands").[67] The titles associated with Maccus appear to relate to a similar one—multarum insularum rex ("king of many islands")—earlier accorded to Amlaíb mac Gofraid, King of Dublin by Chronicon ex chronicis.[68]

The precise reasons for Edgar's assembly are uncertain.[69] It came on the heels of a royal crowning ceremony at Bath, and could have been orchestrated as a way to project imperial authority over Edgar's neighbours.[70] With a grand show of force, Edgar may have sought to demonstrate this authority, and thereby resolve certain outstanding issues with his neighbouring rulers.[71] There is reason to suspect that the upsurge in Viking activity in the 960s/970s,[72] and the emergence of the Meic Arailt in the region, may have factored in Edgar's machinations.[73] Specifically, one aspect of the assembly may have concerned the ongoing warring between the Meic Arailt and the Welsh.[74] Such conflict could have posed a significant threat to the English trade routes in the region, and Edgar may have sought an understanding with Maccus to ensure the safety of important sea-lanes shared with the Islesmen.[75] The threat of international collusion could have also factored into Edgar's assembly.[71] One possibility is that he may have acted to ensure that the Islesmen would not be tempted to lend support to discontented elements in the English Danelaw.[76] It is also conceivable that the assembly could have concerned the remarkable rising power of Amlaíb Cúarán in Ireland.[77] Edgar may have moved to resolve the strife between the Meic Arailt and the Welsh as a way to limit the prospect of any encroachment by Amlaíb Cúarán into the Irish Sea region. This reigning King of Dublin was a leading member of the Uí Ímair,[78] and may have been a rival to the Meic Arailt.[79] By easing tensions between the Meic Arailt and the Welsh, Edgar could have sought to gain their allegiance against Amlaíb Cúarán's ambitions of authority in the area, and further offset any attempt by Amlaíb Cúarán to attain an alliance with the Scots and Cumbrians against the English.[78]

The fact that Brenhinedd y Saesson reports that Gofraid subdued Anglesey and placed it under tribute could indicate that the Meic Arailt were attempting to establish themselves in Britain, and could indicate that the Meic Arailt participated in the assembly in this context.[81] If Maccus was in possession of Mann in the 970s the record of Edgar's assembled fleet could have been a response to the perceived threat that Maccus posed.[82] As such, the episode could well be an example of tenth-century gunboat diplomacy.[83] Other royal attendees of the summit meeting appear to have been Dyfnwal ab Owain,[84] and Dyfnwal's son Máel Coluim,[85] men who represented the Cumbrian Kingdom of Strathclyde.[86][note 6] It is probable that the power of the Meic Arailt posed a serious threat to the rulers of this northern British realm, and may explain their own part in the assembly.[86] One possible result of the conference is that Edgar recognised Maccus' lordship in the Isles in return for his acceptance of English overlordship.[88] Although Maccus appears as a witness in two alleged royal charters of Edgar,[89] these appear to be forgeries.[90]

Later career[]

Whatever the reasons behind the assembly, the Meic Arailt violence in the region was temporarily abated—perhaps as a consequence of the conference[92]—and the kindred turned its attention westwards towards Ireland.[93]

In 974, the eleventh- to fourteenth-century Annals of Inisfallen[94] and the Annals of the Four Masters reveal that Maccus—accompanied by the lagmainn ("lawmen") of the Isles—attacked Scattery Island and captured Ímar, King of Limerick.[95] Ímar appears to have gained the kingship of Limerick in the 960s.[96] If Maccus was indeed a son of Aralt, Maccus' move against Ímar in 974 would appear to corroborate this kinship.[97] For instance, Maccus' attack could have been undertaken in the context of regaining what he regarded as his patrimony, since Ímar's accession in Limerick was conceivably accomplished at the expense of Aralt's progeny.[98]

It is possible that Ímar was in control of Limerick in 969, and may have controlled the town in 972,[99] when the Munstermen are recorded to have expelled the Viking ruling elite.[100] If correct, Ímar's return to power could explain the Meic Arailt kindred's actions against him.[99] Maccus may have ransomed Ímar to the Limerickmen,[101] or Ímar may have escaped his captors.[102] Certainly the Annals of Inisfallen reports that Ímar "escaped over sea" the following year.[103] In any event, Ímar next appears on record three years later when he and his two sons were slain by Brian mac Cennétig, King of Munster.[104][note 7] In 967, Brian's brother, Mathgamain mac Cennétig, is reported to have attacked Limerick.[106] If the eleventh- or twelfth-century Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib is to be believed, Ímar played a role in slaying Mathgamain the year before his own death at Brian's hands. As such, the Meic Arailt and Brian's family appear to have shared a common enemy in the person of Ímar.[107]

The record of Maccus' attack is the second such notice of lagmainn in the Isles. Earlier in 962, the Annals of the Four Masters reports that the lagmainn and the Meic Amlaíb[109]—seemingly the descendants of Amlaíb mac Gofraid[110]—attacked several sites in Ireland.[109] Such lawmen appear to have been elective representatives from the Hebrides,[111] and these annal-entries could be evidence that leading figures in the Irish Sea region received formal support from the Hebrides.[112][note 8] Following Maccus' campaigning against Ímar, nothing is recorded of the Meic Arailt until the 980s.[101] In 984, the Annals of Inisfallen reports that the Meic Arailt contracted an alliance with Brian's family, and exchanged hostages with them in an apparent agreement pertaining to military cooperation against the Kingdom of Dublin.[114] This compact seems to indicate that Brian's family sought to align the Vikings of the Isles against those of Dublin.[115]

Maccus' brother eventually resumed the Meic Arailt attacks upon the Welsh. According to the Peniarth version of Brut y Tywysogyon, a certain Gwrmid—a man who may be identical to Gofraid—ravaged Llŷn in 978.[118] The Red Book of Hergest version of Brut y Tywysogyon reports that Gofraid, along with the exiled Venedotian prince Custennin ab Iago, ravaged Llŷn and Anglesey in 980.[119] The date of Maccus' death is unknown.[120] Since he does not appear on record again, it is possible that he was dead by this date, and that Gofraid had succeeded him in the Isles.[121] On the other hand, the record of the Meic Arailt assisting Brian's family in 984 could be evidence that Maccus was yet still active.[122] In any case, Maccus is certainly unrecorded after 984.[123][note 10] Gofraid's campaigning on Anglesey suggests that whatever authority the Meic Arailt gained over the Welsh in the 970s was only temporary.[126] The fact that there is no record of Viking activity against the island between 972 and 980 suggests that the Meic Arailt's ambitions there had been fulfilled during this span.[41]

In 980, Amlaíb Cúarán was utterly defeated by Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, King of Mide at the Battle of Tara, and retired to Iona where he died soon after. Whilst Islesmen are reported to have supported Amlaíb Cúarán's cause in the conflict, the Meic Arailt are not mentioned, and there is no specific evidence that they did so.[127] On one hand, it is possible that the family supported Amlaíb Cúarán in the conflict.[128] On the other hand, if evidence of contemporary Orcadian encroachment into the Isles is taken into account, there is reason to suspect that the Islesmen present in the conflict were adherents of the earls of Orkney, and did not include the Meic Arailt.[129]

Maccus' brother is the first King of the Isles to recorded as such by Irish sources,[131] when he was styled rí Innse Gall by the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster on his death in 989.[132] The appearance of the kingdom at this time could indicate that the catalyst behind its emergence was Amlaíb Cúarán's defeat at Tara, the subsequent loss of Dublin to Máel Sechnaill's overlordship, and Amlaíb Cúarán's later demise.[133] On one hand, the kingdom could have been a recent creation, perhaps a result of the Meic Arailt gaining overlordship over the Hebridean lagmainn.[134] On the other hand, the first record of a King of the Isles in Irish sources may merely reflect the fact that Dublin had been lost to the Irish after having previously formed part of Amlaíb Cúarán's imperium.[135] In any event, later apparent descendants of Gofraid competed with the descendants of Amlaíb Cúarán for control of a kingdom that encompassed the Hebrides and the Irish Sea region.[136][note 11]

Notes[]

- ^ Since the 1980s, academics have accorded Maccus various patronyms in English secondary sources: Maccus Haraldsson,[2] Maccus Háraldsson,[3] Maccus Haroldson,[4] Maccus mac Arailt,[5] Maccus Mac Arailt,[6] Magnúis Haraldsson,[7] Magnus Haraldsson,[8] Magnús Haraldsson,[7] Magnus mac Arailt,[9] and Magnus mac Arallt.[10]

- ^ The personal name Magnús first appears on record in Scandinavia in the eleventh century, in the person of Magnús Óláfsson, King of Norway.[32]

- ^ Maccus' name is rendered "Marc uab herald" by the Red Book of Hergest version of Brut y Tywysogyon, and "madoc ap harald" by the Peniarth version.[45]

- ^ Early mediaeval burials uncovered at Llanbedrgoch on could be evidence of Manx-based Viking activity on Anglesey.[49]

- ^ The "C" version of Annales Cambriæ merely reports a great gathering of ships at Chester by Edgar.[55]

- ^ If it was not Dyfnwal who attended the assembly, another possibility is that the like-named figure who did was Domnall ua Néill, King of Tara.[87]

- ^ Scattery Island was an ecclesiastical site, and the records of Ímar's defeats on the island appear to indicate that it served as a refuge of the kings of Limerick in times of political upheaval.[105]

- ^ The Gaelic term lagmainn is derived from the Old Norse lǫgmenn ("lawmen").[113]

- ^ If Eiríkr Haraldsson was indeed a member of the Uí Ímair, one possibility is that the sword-emblem represents the "Sword of Carlus", an apparent part of Dublin's royal regalia.[117]

- ^ The disappearance of Maccus from the historical record in the 980s could indicate that he had either died or left the region.[124] One possibility is that Maccus succumbed to plague.[120] Two livestock epidemics are attested by Irish sources in the tenth century: one in 909, another in 987.[125]

- ^ The 980 obituary of Mugrón, Abbot of Iona, preserved by the seventeenth-century Annals of Roscrea, states that he presided over "the Three Parts". One possibility is that this location refers to Fine Gall (including Dublin), the Isles (including Mann), and the Rhinns. If correct, this record could also be evidence of the extent of Amlaíb Cúarán's realm.[137]

Citations[]

- ^ Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.); Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.).

- ^ Clarkson (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013); Downham (2008); Downham (2007); Etchingham (2007); Hewish (2007); Jayakumar (2002); Etchingham (2001); Williams, A (1999).

- ^ a b Williams, A (2004).

- ^ Williams, A (2014).

- ^ Downham (2007).

- ^ Sheehan (2010).

- ^ a b Hudson (1994).

- ^ Redknap (2006); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson (2005); Carr (1982).

- ^ Sheehan; Stummann Hansen; Ó Corráin (2001); Ó Corráin (1998a); Ó Corráin (1998b).

- ^ Omand (2004).

- ^ Duffy (2013) ch. 3.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141.

- ^ Wadden (2016) p. 171; McGuigan (2015b) p. 107; Wadden (2015) pp. 27, 29; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 539, 539 n. 12, 540–541; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Downham (2007) pp. 186–192, 193 fig. 12, 263; Etchingham (2007) p. 157; Hudson (2005) p. 65; Etchingham (2001) pp. 172, 187; Thornton (2001) p. 73; Sellar (2000) p. 190 tab. i; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Jennings, A (1994) pp. 212–213; Meaney (1970) p. 130 n. 161.

- ^ Jennings, A (2015); Wadden (2015) p. 27; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 539, 539 n. 12, 540–541; Jennings, AP (2001).

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 107; Wadden (2015) p. 27; Abrams (2013) p. 60 n. 89; Beougher (2007) pp. 91–92, 92 n. 150; Downham (2007) pp. 186–191; Woolf (2007a) p. 207; Hudson (2005) pp. 68–69, 77, 130 fig. 4.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 107; Wadden (2015) p. 27; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Hudson (2005) p. 65; Sellar (2000) p. 189 n. 9.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218.

- ^ Jennings, A (2015); Wadden (2015) p. 27; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Downham (2007) p. 192; Woolf (2007a) pp. 206, 298; Macniven (2006) p. 68; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Hudson (2005) p. 130 fig. 4; Woolf (2004) p. 99; Etchingham (2001) p. 171; Thornton (2001) p. 73; Sellar (2000) p. 190 tab. i.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 216 n. 54.

- ^ Hudson (2005) p. 61.

- ^ Hudson (2005) p. 61; Dobbs (1931) pp. 189, 228.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 120 n. 74; Woolf (2004) p. 99.

- ^ Naismith (2017) p. 281; Jakobsson (2016) p. 173; McGuigan (2015a) p. 31, 31 n. 48; Downham (2013); Downham (2007) pp. 115–120, 120 n. 74; Woolf (2007a) pp. 187–188; Woolf (2002) p. 39.

- ^ a b Naismith (2017) pp. 281, 300–301; McGuigan (2015a) p. 31, 31 n. 48; Downham (2013); Downham (2007) pp. 119–120, 120 n. 74; Woolf (2002) p. 39.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 940.1; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 940.1; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503 (n.d.).

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 190 n. 27.

- ^ a b Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 972.13; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 972.13; Thornton (2001) p. 72 n. 95; Thornton (1997) pp. 76–77.

- ^ Thornton (1997) p. 73.

- ^ Thornton (1997) p. 77.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 190 n. 26; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Sellar (2000) p. 189 n. 8; Fellows-Jensen (1989–1990) p. 47.

- ^ Wadden (2015) p. 29; Downham (2013a) p. 205; Downham (2007) p. 186; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 141–142; Thornton (1997); Fellows-Jensen (1989–1990) p. 47.

- ^ Insley (1979) p. 58.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 546; Davies, W (2011); Clarke (1981b) pp. 304–305; Anglesey (1960) pp. 121, 123, pls. 180–181.

- ^ a b Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 546.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 546; Davies, W (2011); Clarke (1981a) p. 191.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 107; Wadden (2015) p. 27; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Woolf (2007a) p. 298.

- ^ Wadden (2016) p. 171; Wadden (2015) p. 27; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 540–541; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Oram (2000) p. 10.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Oram (2000) p. 10.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 540–541.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 526.

- ^ a b Downham (2007) p. 222.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015a) p. 43 § b993.1; Williams, A (2014); Downham (2007) pp. 124–125, 221; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Williams, A (2004); Etchingham (2001) pp. 171–172; Davidson (2002) p. 151; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Jennings, A (1994) p. 215.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 539; Downham (2007) pp. 124–125, 221; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Williams, A (2004); Etchingham (2001) pp. 171–172; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Davies, JR (1997) p. 399; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Jennings, A (1994) p. 215; Maund (1993) p. 157; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 539; Downham (2007) pp. 124–125, 221; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Davies, JR (1997) p. 399; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Maund (1993) p. 157; Jones; Williams (1870) p. 658.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 539 n. 11; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Williams, A (2004) n. 50; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Thornton (1997) pp. 85–86; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25; NLW MS. Peniarth 20 (n.d.); Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.).

- ^ Jennings, A (2015); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 539, 546; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Etchingham (2001) pp. 171–172; Ó Corráin (2001) p. 100; Davies, JR (1997) p. 399; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Carr (1982) p. 13.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 221–222, 221 n. 132; Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Redknap (2006) p. 33 n. 77; Jennings, A (1994) p. 215; Maund (1993) p. 157; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 221–222; Maund (1993) p. 157; Jones; Williams (1870) p. 658.

- ^ Redknap (2006) pp. 26–28, 33.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 192, 221.

- ^ O'Keeffe (2001) p. 81; Whitelock (1996) p. 230; Thorpe (1861) p. 226; Cotton MS Tiberius B I (n.d.).

- ^ a b Jennings, A (2015); Wadden (2015) pp. 27–28; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 543; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 31; Aird (2009) p. 309; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Downham (2008) p. 346; Wilson (2008) p. 385; Breeze (2007) p. 155; Downham (2007) pp. 124–125, 167, 222; Matthews (2007) p. 25; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 146, 151; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Etchingham (2001) p. 172; Thornton (2001) p. 72; Oram (2000) p. 10; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Williams, A (1999) p. 116; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Jennings, A (1994) pp. 213–214; Williams; Smyth (1991) p. 124; Meaney (1970) p. 130, 130 n. 161; Stenton (1963) p. 364.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) pp. 143–144, 144 n. 466; Molyneaux (2015) p. 34; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶¶ 9–11, 7 n. 11; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66, 69, 88; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 10; Woolf (2007a) pp. 207–208; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Irvine (2004) p. 59; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 138, 140, 140 n. 140, 144; Thornton (2001) p. 50; Baker (2000) pp. 83–84; Williams, A (1999) pp. 88, 116, 191 n. 50; Whitelock (1996) pp. 229–230; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Stenton (1963) p. 364; Anderson (1908) pp. 75–76; Stevenson, WH (1898); Thorpe (1861) pp. 225–227.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) p. 61 n. 94; McGuigan (2015b) pp. 143–144; Edmonds (2014) p. 206, 206 n. 60; Williams, A (2014); Molyneaux (2011) p. 67; Breeze (2007) p. 154; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 10; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 140–141, 141 n. 145, 145; Thornton (2001) p. 51; Williams, A (1999) pp. 191 n. 50, 203 n. 71; Hudson (1994) pp. 97–98; Jennings, A (1994) pp. 213–214; Anderson (1922) p. 479 n. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898); Skeat (1881) pp. 468–469.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015b) p. 22 § c297.1; Williams, A (2014); Williams, A (1999) p. 116; Anderson (1922) p. 478.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) pp. 143–144, 144 n. 466; Clarkson (2014) chs. 7 ¶¶ 11–12; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66–67; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 11; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 13, 134, 134 n. 111, 142, 145; Etchingham (2001) p. 172; Thornton (2001) pp. 57–58; Oram (2000) p. 10; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Williams, A (1999) pp. 116, 191 n. 50; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Whitelock (1996) pp. 230 n. 1; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Jennings, A (1994) pp. 213–214; Meaney (1970) p. 130; Stenton (1963) p. 364; Anderson (1908) pp. 76–77; Stevenson, WH (1898); Forester (1854) pp. 104–105; Stevenson, J (1853) pp. 247–248; Thorpe (1848) pp. 142–143.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) p. 61 n. 94; McGuigan (2015b) p. 144, 144 n. 466; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 543–544; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66–67; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) pp. 10–11; Karkov (2004) p. 108, 108 n. 123; Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 145; Thornton (2001) pp. 59–60; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Anderson (1908) p. 77 n. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898); Giles (1847) p. 147 bk. 2 ch. 8; Hardy (1840) p. 236 bk. 2 ch. 148.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 144, 144 n. 469; Davidson (2002) p. 142, 142 n. 149, 145; Thornton (2001) pp. 60–61; Anderson (1908) p. 76 n. 2; Arnold (1885) p. 372.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 60; Luard (1872) pp. 466–467.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 60; Giles (1849) pp. 263–264; Coxe (1841) p. 415.

- ^ Luard (2012) p. 513; Thornton (2001) p. 60; Yonge (1853) p. 484.

- ^ Cassell's History of England (1909) p. 53.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 544; Breeze (2007) p. 156; Downham (2007) pp. 125 n. 10, 222; Matthews (2007) p. 25; Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 146, 151; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Thornton (2001) p. 73.

- ^ Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 543; Matthews (2007) p. 10; Karkov (2004) p. 108, 108 n. 123; Williams, A (2004); Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Anderson (1908) p. 77 n. 1; Giles (1847) p. 147 bk. 2 ch. 8; Hardy (1840) p. 236 bk. 2 ch. 148.

- ^ Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 543; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 11; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) p. 134, 134 n. 111, 142; Etchingham (2001) p. 172; Thornton (2001) pp. 57–58, 71–72; Oram (2000) p. 10; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Whitelock (1996) pp. 230 n. 1; Jennings, A (1994) pp. 213–214; Stenton (1963) p. 364; Anderson (1908) p. 76; Forester (1854) p. 105; Stevenson, J (1853) p. 247; Thorpe (1848) p. 142.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 144, 144 n. 469; Davidson (2002) p. 142, 142 n. 149; Thornton (2001) p. 60; Anderson (1908) p. 76 n. 2; Arnold (1885) p. 372.

- ^ Sellar (2000) pp. 189–190; Anderson (1922) p. 478; Stevenson, J (1856) p. 100; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 34.

- ^ Davidson (2002) p. 134, 134 n. 111, 142; Etchingham (2001) p. 172; Sellar (2000) pp. 189–190, 190 n. 12; Anderson (1908) p. 69; Forester (1854) p. 97; Stevenson, J (1853) p. 242; Thorpe (1848) p. 132.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 125.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 545; Downham (2007) pp. 126–127; Keynes (2006) pp. 481–482; Davidson (2002) pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b Downham (2007) p. 126.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 167.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 206; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218.

- ^ Williams, A (2014); Woolf (2009) p. 259; Downham (2007) p. 126.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 126, 194.

- ^ Downham (2008) p. 346.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 545; Davidson (2002) p. 147.

- ^ a b Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 545.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 545; Woolf (2004) p. 99.

- ^ Davidson (2002) p. 142 n. 149; Arnold (1885) p. 372; Cotton MS Domitian A VIII (n.d.).

- ^ Matthews (2007) p. 25; Jones; Williams (1870) p. 658.

- ^ Jennings, A (1994) p. 215.

- ^ Davidson (2002) p. 151.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 543–544; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Breeze (2007) pp. 154–155; Downham (2007) pp. 124, 167; Woolf (2007a) p. 208; Macquarrie (2004); Davidson (2002) p. 143; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Thornton (2001) pp. 54–55, 67; Stenton (1963) p. 324.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams, A (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Minard (2012); Aird (2009) p. 309; Breeze (2007) pp. 154–155; Downham (2007) p. 167; Minard (2006); Macquarrie (2004); Williams, A (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 142–143; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Thornton (2001) pp. 66–67; Williams, A (1999) p. 116; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Jennings, A (1994) p. 215; Stenton (1963) p. 324.

- ^ a b Woolf (2007a) p. 208.

- ^ Davidson (2002) pp. 146–147.

- ^ Etchingham (2007) p. 160; Etchingham (2001) p. 179.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 192 n. 93; Thornton (2001) p. 61, 61 n. 42; O'Brien (1995) pp. 7–8, 8 n. 31; Hudson (1994) pp. 99–100; Thorpe (1865) pp. 245–247 § 971; Kemble (1840) pp. 412–413 § 519; S 808 (n.d.); S 783 (n.d.).

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 192 n. 93; Hudson (2005) p. 72; Barrow (2001) p. 88 n. 38; Thornton (2001); O'Brien (1995) pp. 7–8; S 808 (n.d.); S 783 (n.d.).

- ^ Sheehan (2010) p. 24 fig. 2.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 194, 223; Woolf (2007a) p. 208.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 223; Woolf (2007a) pp. 208, 212.

- ^ Wadden (2015) pp. 28–29; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 974.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 974.2; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Downham (2007) pp. 54, 190, 223, 263; Woolf (2007a) p. 212; Davidson (2002) p. 151, 151 n. 183; Sheehan; Stummann Hansen; Ó Corráin (2001) p. 112; Abrams (1998) p. 21, 21 n. 143; Ó Corráin (1998a) § 16, n. 57; Ó Corráin (1998b) p. 309, 309 n. 59; Jennings, A (1994) p. 212.

- ^ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 972.13; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 972.13; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Abrams (2007) p. 181; Downham (2007) pp. 54, 190, 223, 260, 263; Etchingham (2007) p. 157; Woolf (2007a) pp. 212, 299; Woolf (2007b) pp. 164–165; Macniven (2006) p. 68; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Rekdal (2003–2004) p. 262; Jayakumar (2002) p. 32 n. 87; Etchingham (2001) p. 172; Sheehan; Stummann Hansen; Ó Corráin (2001) p. 112; Thornton (2001) pp. 72–73; Abrams (1998) p. 21, 21 n. 143; Ó Corráin (1998a) § 16, n. 57; Ó Corráin (1998b) p. 309, 309 n. 59; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Thornton (1997) p. 76; Jennings, A (1994) p. 97; Meaney (1970) p. 130 n. 161; Anderson (1922) pp. 479–480.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 73.

- ^ Etchingham (2007) p. 157; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141.

- ^ Wadden (2015) p. 28; Thornton (2001) p. 73.

- ^ a b Etchingham (2001) p. 173.

- ^ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 969.9; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 969.9; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 972.1; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 972.1; Downham (2007) p. 54; Etchingham (2001) p. 173; Jaski (1995) p. 343.

- ^ a b Woolf (2007a) p. 214.

- ^ Downham (2013b) p. 86; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Downham (2007) pp. 54–55.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 975.2; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 975.2.

- ^ The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 977.2; Wadden (2015) p. 28; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 975.8; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 975.8; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Chronicon Scotorum (2012) § 977; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 977.2; Chronicon Scotorum (2010) § 977; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 977.2; Beougher (2007) p. 59; Downham (2007) pp. 55, 194–195, 244, 251, 260; Woolf (2007a) p. 214; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 977.2; Sheehan; Stummann Hansen; Ó Corráin (2001) pp. 112–113; Anderson (1922) p. 480 n. 1; Murphy (1896) p. 158.

- ^ Downham (2014) p. 17; Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Sheehan; Stummann Hansen; Ó Corráin (2001) p. 112.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 967.5; Wadden (2015) p. 28; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 965.14; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 965.14; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 967.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 967.2; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 967.5; Beougher (2007) pp. 31, 62–63; Downham (2007) p. 53; Jaski (1995) pp. 342–343.

- ^ Wadden (2015) p. 28; Todd (1867) pp. 86–89.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015b) p. 23 § c310.1.

- ^ a b Abrams (2007) p. 181; Downham (2007) pp. 184, 263, 265; Woolf (2007a) pp. 213, 299; Woolf (2007b) pp. 164–165; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 960.14; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 960.14; Ó Corráin (1998a) § 16, n. 56; Ó Corráin (1998b) pp. 308–309, 309 n. 58.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 539–540; Downham (2007) pp. 185, 219.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 540; Downham (2007) p. 185; Woolf (2007a) pp. 213, 299–300; Woolf (2001).

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 185; Woolf (2007a) p. 213; Woolf (2007b) p. 165.

- ^ Sheehan (2010) p. 25; Downham (2007) p. 49; Etchingham (2001) p. 172.

- ^ Downham (2011) pp. 197–198; Wadden (2015) pp. 17, 28–29; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 527; Downham (2013b) p. 86; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 984.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 984.2; Beougher (2007) p. 88; Woolf (2007a) pp. 216–217; Hudson (2005) p. 62.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 198–199.

- ^ Downham (2013a) pp. 202–203; Downham (2007) pp. 119–120.

- ^ Naismith (2017) pp. 300–301.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 546; Downham (2007) p. 223; Maund (1993) pp. 55, 157; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 26–27.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 223; Etchingham (2007) p. 157; Woolf (2007a) p. 217; Jennings, A (1994) p. 216; Maund (1993) pp. 55, 158; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Hudson (2005) p. 62.

- ^ Jennings, A (1994) p. 216 n. 33.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 527; Jennings, A (1994) p. 216 n. 33.

- ^ Etchingham (2007) p. 158; Hudson (2005) p. 62; Etchingham (2001) p. 176.

- ^ Wadden (2016) p. 172.

- ^ Ó Corráin (2008) p. 576.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 222; Etchingham (2007) p. 157.

- ^ Etchingham (2007) p. 157; Hudson (2005) p. 65; Etchingham (2001) pp. 173–175.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 223.

- ^ Etchingham (2001) pp. 174–175.

- ^ The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 989.3; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 989.3; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ^ Wadden (2016) p. 172; Woolf (2007a) pp. 219, 298.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 989.4; Clancy (2008) p. 26; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 989.4; Woolf (2007a) pp. 219, 298; Woolf (2007b) p. 165; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Anderson (1922) p. 494.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) pp. 219, 298.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) pp. 219, 298–300; Woolf (2007b) pp. 164–165.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 219.

- ^ Woolf (2007a) p. 298.

- ^ Wadden (2016) p. 171; Gleeson; MacAirt (1957–1959) p. 171 § 290.

References[]

Primary sources[]

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1908). Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers, A.D. 500 to 1286. London: David Nutt. OL 7115802M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. OL 14712679M.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (23 October 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 February 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1885). Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 2. London: Longmans & Co.

- Baker, PS, ed. (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. 8. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-490-9.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Cassell's History of England: From the Roman Invasion to the Wars of the Roses. 1. London: Cassell and Company. 1909. OL 7042010M.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 March 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (14 May 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Cotton MS Domitian A VIII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- "Cotton MS Tiberius B I". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Coxe, HE, ed. (1841). Rogeri de Wendover Chronica, sive Flores Historiarum. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871700M.

- Dobbs, ME, ed. (1931). "The Ban-Shenchus". Revue Celtique. 48: 163–234.

- Forester, T, ed. (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester, with the Two Continuations: Comprising Annals of English History, From the Departure of the Romans to the Reign of Edward I. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 24871176M.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1847). William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England, From the Earliest Period to the Reign of King Stephen. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Gleeson, D; MacAirt, S (1957–1959). "The Annals of Roscrea". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 59C: 137–180. eISSN 2009-0048. ISSN 0035-8991. JSTOR 25505079.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015a). Annales Cambriae: The B Text From London, National Archives, MS E164/1, pp. 2–26 (PDF) (September 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015b). Annales Cambriae: The C Text From London, British Library, Cotton MS Domitian A. i, ff. 138r–155r (PDF) (September 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Hardy, TD, ed. (1840). Willelmi Malmesbiriensis Monachi Gesta Regum Anglorum Atque Historia Novella. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871887M.

- Irvine, S, ed. (2004). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. 7. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-494-1.

- "Jesus College MS. 111". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Jones, O; Williams, E; Pughe, WO, eds. (1870). The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales. Denbigh: Thomas Gee. OL 6930827M.

- Kemble, JM, ed. (1840). Codex Diplomaticus Aevi Saxonici. 2. London: English Historical Society.

- Luard, HR, ed. (1872). Matthæi Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora. 1. London: Longman & Co.

- Luard, HR, ed. (2012) [1890]. Flores Historiarum. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139382960. ISBN 978-1-108-05334-1.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1896). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. OL 7064857M.

- O'Keeffe, KO, ed. (2001). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. 5. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-491-7.

- "Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (The Red Book of Hergest)". Welsh Prose 1300–1425. n.d. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "NLW MS. Peniarth 20". Welsh Prose 1300–1425. n.d. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Rhŷs, J; Evans, JG, eds. (1890). The Text of the Bruts From the Red Book of Hergest. Oxford. OL 19845420M.

- "S 783". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. n.d. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "S 808". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. n.d. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Skeat, W, ed. (1881). Ælfric's Lives of Saints. Third series. 1. London: Early English Text Society.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1835). Chronica de Mailros. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 13999983M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1853). The Church Historians of England. 2, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1856). The Church Historians of England. 4, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (8 February 2016 ed.). University College Cork. 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (6 January 2017 ed.). University College Cork. 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1848). Florentii Wigorniensis Monachi Chronicon ex Chronicis. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871544M.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1865). Diplomatarium Anglicum Ævi Saxonici: A Collection of English Charters. London: Macmillan & Co. OL 21774758M.

- Todd, JH, ed. (1867). Cogad Gaedel re Gallaib: The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. OL 24826667M.

- Whitelock, D, ed. (1996) [1955]. English Historical Documents, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-43950-3.

- Williams Ab Ithel, J, ed. (1860). Brut y Tywysigion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. OL 24776516M.

- Yonge, CD, ed. (1853). The Flowers of History. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 7154619M.

Secondary sources[]

- Abrams, L (1998). "The Conversion of the Scandinavians of Dublin". In Harper-Bill, C (ed.). Anglo-Norman Studies. 20. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 1–29. ISBN 0-85115-573-1. ISSN 0954-9927.

- Abrams, L (2007). "Conversion and the Church in the Hebrides in the Viking Age". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Abrams, L (2013). "Early Normandy". In Bates, D (ed.). Anglo-Norman Studies. 35. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 45–64. ISBN 978-1-84383-857-9. ISSN 0954-9927.

- Aird, WM (2009). "Northumbria". In Stafford, P (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Blackwell Companions to British History. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 303–321. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3.

- Anglesey: A Survey and Inventory by the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1960 [1937].

- Barrow, J (2001). "Chester's Earliest Regatta? Edgar's Dee-Rowing Revisited". Early Medieval Europe. 10 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00080. eISSN 1468-0254.

- Beougher, DB (2007). Brian Boru: King, High-King, and Emperor of the Irish (PhD thesis). Pennsylvania State University.

- Breeze, A (2007). "Edgar at Chester in 973: A Breton Link?". Northern History. 44 (1): 153–157. doi:10.1179/174587007X165405. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 161204995.

- Carr, AD (1982). Medieval Anglesey. Studies in Anglesey History Series. Llangefni: Anglesey Antiquarian Society.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. The History of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clancy, TO (2008). "The Gall-Ghàidheil and Galloway" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 2: 19–51. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Clarke, JE (1981a). Welsh Sculptured Crosses and Cross-Slabs of the Pre-Norman Period (PhD thesis). 1. University College London.

- Clarke, JE (1981b). Welsh Sculptured Crosses and Cross-Slabs of the Pre-Norman Period (PhD thesis). 2. University College London.

- Clarkson, T (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-25-2.

- Davidson, MR (2002). Submission and Imperium in the Early Medieval Insular World (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/23321.

- Davies, JR (1997). "Church, Property, and Conflict in Wales, AD 600–1100". The Welsh History Review. 18 (3): 387–406. eISSN 0083-792X. hdl:10107/1082967. ISSN 0043-2431.

- Davies, W (2011) [1990]. "Vikings". Patterns of Power in Early Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–60. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198201533.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-820153-3 – via Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Downham, C (2008). "Vikings in England". In Brink, S; Price, N (eds.). The Viking World. Routledge Worlds. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 341–376. ISBN 978-0-203-41277-0.

- Downham, C (2011). "Viking Identities in Ireland: It's not all Black and White". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. 11. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 185–201.

- Downham, C (2013a). "Eric Bloodaxe – Axed? The Mystery of the Last Scandinavian King of York". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 181–208. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Downham, C (2013b). "Irish Chronicles as a Source for Rivalry Between Vikings, A.D. 795–1014". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 75–89. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Downham, C (2014). "Vikings' Settlements in Ireland Before 1014". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Duffy, S (2013). Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf. Gill & Macmillan.

- Edmonds, F (2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". Scottish Historical Review. 93 (2): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Edmonds, F (2015). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23 (1): 43–66. doi:10.1111/emed.12087. eISSN 1468-0254.

- Etchingham, C (2001). "North Wales, Ireland and the Isles: the Insular Viking Zone". Peritia. 15: 145–187. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.434. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Etchingham, C (2007). "Viking-Age Gwynedd and Ireland: Political Relations". In Wooding, JM; Jankulak, K (eds.). Ireland and Wales in the Middle Ages. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 149–167. ISBN 978-1-85182-748-0.

- Fellows-Jensen, G (1989–1990). "Scandinavians in Southern Scotland?" (PDF). Nomina. 8: 41–58. ISSN 0141-6340.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Hewish, J (2007). "Review of B Hudson, Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion and Empire in the North Atlantic". The Medieval Review. ISSN 1096-746X.

- Hudson, BT (1994). Kings of Celtic Scotland. Contributions to the Study of World History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29087-3. ISSN 0885-9159. Archived from the original on 2019-06-23. Retrieved 2019-06-24.

- Hudson, BT (2005). Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516237-0.

- Insley, J (1979). "Regional Variation in Scandinavian Personal Nomenclature in England" (PDF). Nomina. 3: 52–60. ISSN 0141-6340.

- Jakobsson, S (2016). "The Early Kings of Norway, the Issue of Agnatic Succession, and the Settlement of Iceland". Viator. 47 (3): 171–188. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.112357. eISSN 2031-0234. ISSN 0083-5897.

- Jaski, B (1995). "The Vikings and the Kingship of Tara". Peritia. 9: 310–353. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.254. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Jayakumar, J (2002). "The 'Foreign Policies' of Edgar 'the Peaceable'". In Morillo, S (ed.). The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. 10. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 17–37. ISBN 0-85115-911-7. ISSN 0963-4959. OL 8277739M.

- Jennings, A (1994). Historical Study of the Gael and Norse in Western Scotland From c.795 to c.1000 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/15749.

- Jennings, A (2015) [1997]. "Isles, Kingdom of the". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (eds.). The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 – via Oxford Reference.

- Jennings, AP (2001). "Man, Kingdom of". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Karkov, CE (2004). The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England. Anglo-Saxon Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-059-0. ISSN 1475-2468.

- Keynes, S (2006) [1999]. "England, 900–1016". In Reuter, T (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–484. ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8.

- Macniven, A (2006). The Norse in Islay: A Settlement Historical Case-Study for Medieval Scandinavian Activity in Western Maritime Scotland (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/8973.

- Macquarrie, A (2004). "Donald (d. 975)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49382. Retrieved 19 June 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Matthews, S (2007). "King Edgar, Wales and Chester: The Welsh Dimension in the Ceremony of 973". Northern History. 44 (2): 9–26. doi:10.1179/174587007X208209. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 159699748.

- Maund, KL (1993) [1991]. Ireland, Wales and England in the Eleventh Century. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-533-3.

- McGuigan, N (2015a). "Ælla and the Descendants of Ivar: Politics and Legend in the Viking Age". Northern History. 52 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1179/0078172X14Z.00000000075. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 161252048.

- McGuigan, N (2015b). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7829.

- Meaney, AL (1970). "Æthelweard, Ælfric, the Norse Gods and Northumbria". Journal of Religious History. 6 (2): 105–132. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1970.tb00557.x. eISSN 1467-9809.

- Minard, A (2006). "Cumbria". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 514–515. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Minard, A (2012). "Cumbria". In Koch, JT; Minard, A (eds.). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-1-59884-964-6.

- Molyneaux, G (2011). "Why Were Some Tenth-Century English Kings Presented as Rulers of Britain?". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 21: 59–91. doi:10.1017/S0080440111000041. eISSN 1474-0648. ISSN 0080-4401.

- Molyneaux, G (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Naismith, R (2017). Naismith, Rory (ed.). Medieval European Coinage. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139031370. ISBN 9780521260169.

- O'Brien, B (1995). "Forgery and the Literacy of the Early Common Law". Albion. 27 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0095139000018500. ISSN 0095-1390.

- Omand, D, ed. (2004). "Index". The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 277–304. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Oram, RD (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-541-5.

- Oram, RD (2011) [2001]. The Kings & Queens of Scotland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7099-3.

- Ó Corráin, D (1998a). "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century". Chronicon: An Electric History Journal. 2. ISSN 1393-5259.

- Ó Corráin, D (1998b). "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century". Peritia. 12: 296–339. doi:10.1484/j.peri.3.334. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Ó Corráin, D (2001) [1997]. "Ireland, Wales, Man, and the Hebrides". In Sawyer, P (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–109. ISBN 0-19-285434-8.

- Ó Corráin, D (2008) [2005]. "Ireland c.800: Aspects of Society". In Ó Cróinín, D (ed.). Prehistoric and Early Ireland. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 549–608. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Redknap, M (2006). "Viking-Age Settlement in Wales: Some Recent Advances". Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. 12: 5–35. ISSN 0959-3632.

- Rekdal, JE (2003–2004). "Vikings and Saints–Encounters Vestan um Haf". Peritia. 17–18: 256–275. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.536. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sheehan, J (2010). "The Character and Cultural Context of the Inis Cáthaig/Scattery Island Silver Hoard". The Other Clare. 34: 23–28. hdl:10468/3285.

- Sheehan, J; Stummann Hansen, S; Ó Corráin, D (2001). "A Viking Age Maritime Haven: A Reassessment of the Island Settlement at Beginish, Co. Kerry". The Journal of Irish Archaeology. 10: 93–119. ISSN 0268-537X. JSTOR 30001672.

- Stenton, F (1963). Anglo-Saxon England. The Oxford History of England (2nd ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press. OL 24592559M.

- Stevenson, WH (1898). "The Great Commendation to King Edgar in 973". English Historical Review. 13 (51): 505–507. doi:10.1093/ehr/XIII.LI.505. eISSN 1477-4534. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 547617.

- Thornton, DE (1997). "Hey, Mac! The Name Maccus, Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries". Nomina. 20: 67–98. ISSN 0141-6340.

- Thornton, DE (2001). "Edgar and the Eight Kings, AD 973: Textus et Dramatis Personae". Early Medieval Europe. 10 (1): 49–79. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00079. eISSN 1468-0254. hdl:11693/24776.

- Wadden, P (2015). "The Normans and the Irish Sea World in the Era of the Battle of Clontarf". In McAlister, V; Barry, T (eds.). Space and Settlement in Medieval Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 15–33. ISBN 978-1-84682-500-2.

- Wadden, P (2016). "Dál Riata c. 1000: Genealogies and Irish Sea Politics". Scottish Historical Review. 95 (2): 164–181. doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0294. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Walker, IW (2013) [2006]. Lords of Alba: The Making of Scotland (EPUB). Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9519-4.

- Williams, A (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England, c.500–1066. British History in Perspective. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-27454-3. ISBN 978-1-349-27454-3.

- Williams, A (2004). "An Outing on the Dee: King Edgar at Chester, AD 973". Mediaeval Scandinavia. 14: 229–243.

- Williams, A (2014). "Edgar (943/4–975)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January 2014 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8463. Retrieved 29 June 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, A; Smyth, AP; Kirby, DP (1991). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: England, Scotland and Wales, c.500–c.1050. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Williams, DGE (1997). Land Assessment and Military Organisation in the Norse Settlements in Scotland, c.900–1266 AD (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7088.

- Wilson, DM (2008). "The Isle of Man". In Brink, S; Price, N (eds.). The Viking World. Routledge Worlds. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 385–390. ISBN 978-0-203-41277-0.

- Woolf, A (2001). "Isles, Kingdom of the". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 346–347. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Woolf, A (2002). "Amlaíb Cuarán and the Gael, 941–81". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. 3. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 34–43.

- Woolf, A (2004). "The Age of Sea-Kings, 900–1300". In Omand, D (ed.). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 94–109. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Woolf, A (2007a). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

- Woolf, A (2007b). "The Wood Beyond the World: Jämtland and the Norwegian Kings". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 153–166. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Woolf, A (2009). "Scotland". In Stafford, P (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Blackwell Companions to British History. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 251–267. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3.

External links[]

![]() Media related to Maccus mac Arailt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maccus mac Arailt at Wikimedia Commons

- 10th-century rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles

- 10th-century monarchs in Europe

- 10th-century Scottish people

- Monarchs of the Isle of Man

- Norse-Gaelic monarchs

- Rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles

- Uí Ímair