Mansa Musa

| Musa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

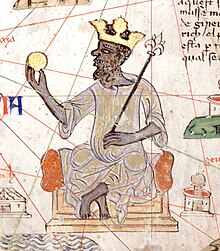

Musa depicted holding an Imperial Golden Globe in the 1375 Catalan Atlas. | |||||

| Mansa of Mali | |||||

| Reign | c.1312– c.1337 (c. 25 years) | ||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad ibn Qu[1] | ||||

| Successor | Maghan Musa | ||||

| Born | c. 1280 Mali Empire | ||||

| Died | c. 1337 (aged 56–57) Mali Empire | ||||

| Spouse | Inari Kunate | ||||

| Issue | Maghan Musa | ||||

| |||||

| House | Keita Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Faga Laye | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Musa I (c. 1280[citation needed] – c. 1337), or Mansa Musa, was the ninth[2] Mansa of the Mali Empire, an Islamic West African state.

At the time of Musa's ascension to the throne, Mali in large part consisted of the territory of the former Ghana Empire, which Mali had conquered. The Mali Empire consisted of land that is now part of Guinea, Senegal, Mauritania, Gambia and the modern state of Mali.

Musa conquered 24 cities, along with their surrounding districts.[3] During Musa's reign, Mali may have been the largest producer of gold in the world, and Musa has been called one of the wealthiest historical figures,[4] though there is no accurate way to quantify his wealth.[5]

In 1324–1325, Musa performed the hajj. En route, he spent time in Cairo, where his lavish gift-giving caused a noticeable drop in the price of gold for over a decade. After completing the hajj, Musa returned to Mali, annexing the cities of Gao and Timbuktu upon his return.

Name and titles[]

Mansa Musa's personal name was Musa (Arabic: موسى, romanized: Mūsā), the Arabic form of Moses. Mansa, 'ruler'[6] or 'king'[7] in Mande, was the title of the ruler of the Mali Empire. It has also been translated as "conqueror" and "priest-king".[8][9] In oral tradition and the Timbuktu Chronicles, Musa is known as Kanku Musa.[10][a] In Mande tradition, it was common for one's name to be prefixed by their mother's name, so the name Kanku Musa means "Musa, son of Kanku", although it is unclear if the geneaology implied is literal.[14] He is also called Hidji Mansa Musa in oral tradition in reference to his hajj.[15] As he was a member of the Keita dynasty, he is also called Musa Keita.

In the Songhai language, rulers of Mali such as Musa were known as the Mali-koi, koi being a title that conveyed authority over a region: in other words, the "ruler of Mali".[16]

Historical sources[]

Much of what is known about Musa comes from Arabic sources written after his hajj, especially the writings of Al-Umari and Ibn Khaldun. While in Cairo during his hajj, Musa befriended officials such as Ibn Amir Hajib, who learned about him and his country from him and later passed on that information to historians such as Al-Umari.[17] Mande oral tradition, though a rich source of information for other events in the history of the Mali Empire, contains relatively little information about Musa. Additional information comes from two 17th-century manuscripts written in Timbuktu, the Tarikh as-Sudan and the Tarikh al-fattash.[18]

Lineage and accession to the throne[]

Musa's father was named Faga Leye[20] and his mother may have been named Kanku.[b] Faga Leye was the son of Abu Bakr, a brother of Sunjata, the first mansa of the Mali Empire.[22][c] Ibn Battuta, who visited Mali during the reign of Musa's brother Sulayman, said that Musa's grandfather was named Sariq Jata.[24] Sariq Jata may be another name for Sunjata, who was actually Musa's great-uncle.[25] The date of Musa's birth is unknown, but he still appeared to be a young man in 1324.[26] The Tarikh al-fattash claims that Musa accidentally killed Kanku at some point prior to his hajj.[27]

Musa ascended to power in the early 1300s[d] under unclear circumstances. According to Musa's own account, his predecessor as mansa of Mali, presumably Muhammad ibn Qu,[30] launched two expeditions to explore the Atlantic Ocean. The mansa led the second expedition himself, and appointed Musa as his deputy to rule the empire until he returned.[31] When he did not return, Musa was crowned as mansa himself, marking a transfer of the line of succession from the descendants of Sunjata to the descendants of his brother Abu Bakr.[32] Some modern historians have cast doubt on Musa's version of events, suggesting he may have deposed his predecessor and devised the story about the voyage to explain how he took power.[33][34]

Islam and pilgrimage to Mecca[]

From the far reaches of the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus River, the faithful approached the city of Mecca. All had the same objective to worship together at the most sacred shrine of Islam, the Kaaba in Mecca. One such traveler was Mansa Musa, Sultan of Mali in Western Africa. Mansa Musa had prepared carefully for the long journey he and his attendants would take. He was determined to travel not only for his own religious fulfillment but also for recruiting teachers and leaders so that his realms could learn more of the Prophet's teachings.

–Mahmud Kati, Chronicle of the Seeker

Musa was a devout Muslim, and his pilgrimage to Mecca, also known as Makkah, made him well known across Northern Africa and the Middle East. To Musa, Islam was "an entry into the cultured world of the Eastern Mediterranean".[35] He would have spent much time fostering the growth of the religion within his empire.

Musa made his pilgrimage between 1324 and 1325 spanning 2,700 miles.[36][37][38] His procession reportedly included 60,000 men, all wearing brocade and Persian silk, including 12,000 slaves,[39] who each carried 1.8 kg (4 lb) of gold bars, and heralds dressed in silks, who bore gold staffs, organized horses, and handled bags. Musa provided all necessities for the procession, feeding the entire company of men and animals.[35] Those animals included 80 camels which each carried 23–136 kg (50–300 lb) of gold dust. Musa gave the gold to the poor he met along his route. Musa not only gave to the cities he passed on the way to Mecca, including Cairo and Medina, but also traded gold for souvenirs. It was reported that he built a mosque every Friday.[40]

Musa's journey was documented by several eyewitnesses along his route, who were in awe of his wealth and extensive procession, and records exist in a variety of sources, including journals, oral accounts, and histories. Musa is known to have visited the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, Al-Nasir Muhammad, in July 1324.[41] Because of his nature of giving, Musa's massive spending and generous donations created a massive ten year gold recession. In the cities of Cairo, Medina, and Mecca, the sudden influx of gold devalued the metal significantly. Prices of goods and wares became greatly inflated. This mistake became apparent to Musa and on his way back from Mecca, he borrowed all of the gold he could carry from money-lenders in Cairo at high interest. This is the only time recorded in history that one man directly controlled the price of gold in the Mediterranean.[35] Some historians[who?] believe the Hajj was less out of religious devotion than to garner international attention to the flourishing state of Mali. Al-Umari who visited Cairo shortly after Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca, noted that it was "a lavish display of power, wealth, and unprecedented by its size and pageantry".[42] The creation of a recession of that magnitude could have been purposeful. After all, Cairo was the leading gold market at the time (where people went to purchase large amounts of gold). In order to relocate these markets to Timbuktu or Gao, Musa would have to first affect Cairo's gold economy. Musa made a major point of showing off his nation's wealth. His goal was to create a ripple and he succeeded greatly in this, so much so that he landed himself and Mali on the Catalan Atlas of 1375.[citation needed]

Later reign[]

Whenever a hero adds to the list of his exploits, the king gives him a pair of wide trousers, and the greater the number of a knight's exploits, the bigger the size of his trousers.

–Al-Umari describing the Honor of the Trousers[43]

During his long return journey from Mecca in 1325, Musa heard news that his army had recaptured Gao. Sagmandia, one of his generals, led the endeavor. The city of Gao had been within the empire since before Sakura's reign and was an important − though often rebellious − trading center. Musa made a detour and visited the city where he received, as hostages, the two sons of the Gao king, Ali Kolon and Suleiman Nar. He returned to Niani with the two boys and later educated them at his court. When Mansa Musa returned, he brought back many Arabian scholars and architects.[44]

Construction in Mali[]

Musa embarked on a large building program, raising mosques and madrasas in Timbuktu and Gao. Most notably, the ancient center of learning Sankore Madrasah (or University of Sankore) was constructed during his reign.

In Niani, Musa built the Hall of Audience, a building communicating by an interior door to the royal palace. It was "an admirable Monument", surmounted by a dome and adorned with arabesques of striking colours. The wooden window frames of an upper storey were plated with silver foil; those of a lower storey with gold. Like the Great Mosque, a contemporaneous and grandiose structure in Timbuktu, the Hall was built of cut stone.

During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian scholar of art and architecture, wrote of this period: "Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the Niger Delta was very densely populated."[45]

Economy and education[]

It is recorded that Mansa Musa traveled through the cities of Timbuktu and Gao on his way to Mecca, and made them a part of his empire when he returned around 1325. He brought architects from Andalusia, a region in Spain, and Cairo to build his grand palace in Timbuktu and the great Djinguereber Mosque that still stands today.[46]

Timbuktu soon became the center of trade, culture, and Islam; markets brought in merchants from Hausaland, Egypt, and other African kingdoms, a university was founded in the city (as well as in the Malian cities of Djenné and Ségou), and Islam was spread through the markets and university, making Timbuktu a new area for Islamic scholarship.[47] News of the Malian empire's city of wealth even traveled across the Mediterranean to southern Europe, where traders from Venice, Granada, and Genoa soon added Timbuktu to their maps to trade manufactured goods for gold.[48]

The University of Sankore in Timbuktu was restaffed under Musa's reign with jurists, astronomers, and mathematicians.[49] The university became a center of learning and culture, drawing Muslim scholars from around Africa and the Middle East to Timbuktu.

In 1330, the kingdom of Mossi invaded and conquered the city of Timbuktu. Gao had already been captured by Musa's general, and Musa quickly regained Timbuktu, built a rampart and stone fort, and placed a standing army to protect the city from future invaders.[50]

While Musa's palace has since vanished, the university and mosque still stand in Timbuktu today.

By the end of Mansa Musa's reign, the Sankoré University had been converted into a fully staffed University with the largest collections of books in Africa since the Library of Alexandria. The Sankoré University was capable of housing 25,000 students and had one of the largest libraries in the world with roughly 1,000,000 manuscripts.[51][52]

Death[]

The date of Mansa Musa's death is not certain. Using the reign lengths reported by Ibn Khaldun to calculate back from the death of Mansa Suleyman in 1360, Musa would have died in 1332.[53] However, Ibn Khaldun also reports that Musa sent an envoy to congratulate Abu al-Hasan Ali for his conquest of Tlemcen, which took place in May 1337, but by the time Abu al-Hasan sent an envoy in response, Musa had died and Suleyman was on the throne, suggesting Musa died in 1337.[54] In contrast, al-Umari, writing twelve years after Musa's hajj, in approximately 1337,[55] claimed that Musa returned to Mali intending to abdicate and return to live in Mecca but died before he could do so,[56] suggesting he died even earlier than 1332.[57] It is possible that it was actually Musa's son Maghan who congratulated Abu al-Hasan, or Maghan who received Abu al-Hasan's envoy after Musa's death.[58] The latter possibility is corroborated by Ibn Khaldun calling Suleyman Musa's son in that passage, suggesting he may have confused Musa's brother Suleyman with Musa's son Maghan.[59] Alternatively, it is possible that the four-year reign Ibn Khaldun credits Maghan with actually referred to his ruling Mali while Musa was away on the hajj, and he only reigned briefly in his own right.[60] Nehemia Levtzion regarded 1337 as the most likely date,[54] which has been accepted by other scholars.[61][62]

Legacy[]

Musa's hajj has been regarded as the most illustrious moment in the history of West Africa.[63]

Musa is less renowned in Mande oral tradition.[64] Some jeliw regard Musa as having wasted Mali's wealth.[65]

Mande oral tradition features a figure known as Fajigi, which translates as "father of hope".[66] Fajigi is at least partially based on Musa, but may incorporate aspects of other figures as well.[66] Fajigi is remembered as having traveled to Mecca to retrieve ceremonial objects known as boliw, which feature in Mande traditional religion.[66] As Fajigi, Musa is sometimes conflated with a figure in oral tradition named Fakoli, who is best-known as Sunjata's top general.[67] The figure of Fajigi combines both Islam and traditional beliefs.[66]

The name "Musa" has become virtually synonymous with pilgrimage in Mande tradition, such that other figures who are remembered as going on a pilgrimage, such as Fakoli, are also called Musa.[68]

Wealth[]

Musa has been considered the wealthiest human ever.[69] Though some sources have estimated his wealth as equivalent to US$400 billion, his actual wealth is impossible to accurately calculate. Musa may have brought as much as 18 tons of gold on his hajj.[70]

In popular culture[]

- Mansa Musa leads the Malian civilization in the Gathering Storm expansion of the 4X video game Civilization VI.[71]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Several alternate spellings exist, such as Congo Musa, Gongo Musa, and Kankan Musa, but they are regarded as incorrect.[11][12][13]

- ^ Musa's name Kanku Musa means "Musa son of Kanku", but the geneaology may not be literal.[21]

- ^ Arabic sources omit Faga Leye, referring to Musa as Musa ibn Abi Bakr. This can be interpreted as meaning either "Musa son of Abu Bakr" or "Musa descendant of Abu Bakr." It is implausible that Abu Bakr was Musa's father, due to the amount of time between Sunjata's reign and Musa's.[23]

- ^ The exact date of Musa's accession is debated. Ibn Khaldun claims Musa reigned for 25 years, so his accession is dated to 25 years before his death. Musa's death may have occurred in 1337, 1332, or possibly even earlier, giving 1307 or 1312 as plausible approximate years of accession. 1312 is the most widely accepted by modern historians.[28][29]

References[]

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 346

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 353

- ^ C. Conrad, David (1 January 2009). Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. Infobase Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-1438103198. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Thad Morgan, "This 14th-Century African Emperor Remains the Richest Person in History" Archived 2019-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, History.com, March 19, 2018

- ^ Davidson, Jacob (July 30, 2015). "The 10 Richest People of All Time". Time. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 87

- ^ MacBrair 1873, p. 40

- ^ Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd edn. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 455.

- ^ Jansen 1998, p. 256

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 230

- ^ Niane 1959

- ^ Hunwick 1999, p. 9

- ^ Cissoko 1969

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 109

- ^ Niane 1959.

- ^ Gomez 2018, pp. 109,129

- ^ Al-Umari, Chapter 10.

- ^ Gomez 2018, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 353.

- ^ Niane 1959

- ^ Gomez 2018, pp. 109–110

- ^ Niane 1959

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 347

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 295.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 416.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 104

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 109

- ^ Bell 1972

- ^ Levtzion 1963, pp. 349–350

- ^ Fauvelle 2018

- ^ Al-Umari, Chapter 10

- ^ Ibn Khaldun

- ^ Gomez 2018

- ^ Thornton 2012, pp. 9,11

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Goodwin 1957, p. 110.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ^ Wilks, Ivor (1997). "Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Bakewell, Peter John (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 7. ISBN 9780860785132.

- ^ de Graft-Johnson, John Coleman, "Mūsā I of Mali" Archived 2017-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica, 15 November 2017.

- ^ Bell 1972

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 224

- ^ The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa By Patricia McKissack, Fredrick McKissack Page 60

- ^ Mendoza 2001, p. 293.

- ^ Windsor, Rudolph R. (2011). From Babylon to Timbuktu: A History of Ancient Black Races Including the Black Hebrews (Windsor's golden series ed.). AuthorHouse. pp. 95–98. ISBN 978-1463411299. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Mansa Musa, African History Restored, 2008, archived from the original on 2 October 2008, retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ De Villiers and Hirtle, p. 70.

- ^ De Villiers and Hirtle, p. 74.

- ^ De Villiers and Hirtle, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Goodwin 1957, p. 111.

- ^ De Villiers and Hirtle, pp. 80–81.

- ^ See: Said Hamdun & Noël King (edds.), Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. London, 1975, pp. 52–53.

- ^ "Lessons from Timbuktu: What Mali's Manuscripts Teach About Peace | World Policy Institute". Worldpolicy.org. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 349.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levtzion 1963, p. 350.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 252,413.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 268.

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 224.

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 225–226.

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 225.

- ^ Bell 1972, p. 226–227.

- ^ Sapong 2016, p. 2.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 145.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 4

- ^ Gomez 2018, pp. 92–93

- ^ Mohamud 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Conrad 1992, p. 152.

- ^ Conrad 1992, p. 153.

- ^ Conrad 1992, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Mohamud 2019

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 106

- ^ "Civilization® VI – the Official Site | News | Civilization VI: Gathering Storm – Mansa Musa Leads Mali".

Bibliography[]

- Al-Umari, Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar, translated by Levtzion, N.; Hopkins, J. F. P.

- Bell, Nawal Morcos (1972), "The age of Mansa Musa of Mali: Problems in succession and chronology", International Journal of African Historical Studies, 5 (2): 221–234, doi:10.2307/217515, JSTOR 217515

- Conrad, David C. (1992). "Searching for History in The Sunjata Epic: The Case of Fakoli". History in Africa. 19: 147–200. doi:10.2307/3171998. eISSN 1558-2744. ISSN 0361-5413.

- Cissoko, S. M. (1969), "Quel est le nom du plus grand empereur du Mali: Kankan Moussa ou Kankou Moussa", Notes Africaines, 124: 113–114

- De Villiers, Marq; Hirtle, Sheila (2007). Timbuktu: Sahara's fabled city of gold. New York: Walker and Company.

- Gomez, Michael A. (2018). African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691196824.

- Goodwin, A. J .H. (1957), "The Medieval Empire of Ghana", South African Archaeological Bulletin, 12 (47): 108–112, doi:10.2307/3886971, JSTOR 3886971.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Ibn Khaldun, Kitab al-'Ibar, translated by Levtzion, N.; Hopkins, J. F. P.

- Jansen, Jan (1998). "Hot Issues: The 1997 Kamabolon Ceremony in Kangaba (Mali)". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 31 (2): 253–278. doi:10.2307/221083. hdl:1887/2774. JSTOR 221083.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1963), "The thirteenth- and fourteenth-century kings of Mali", Journal of African History, 4 (3): 341–353, doi:10.1017/s002185370000428x, JSTOR 180027.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F. P., eds. (2000) [1981], Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 1-55876-241-8.

- MacBrair, R. Maxwell (1873), A Grammar of the Mandingo Language: With Vocabularies, London: John Mason

- Mendoza, Ruben G. (2001). "West African empires. Dates: 400–1591 C. E.". In Powell, John (ed.). Weapons & Warfare. Volume 1. Ancient and Medieval Weapons and Warfare to 1500. Salem Press. pp. 291–295. ISBN 1-58765-000-2.

|volume=has extra text (help) - Mohamud, Naima (2019-03-10). "Is Mansa Musa the richest man who ever lived?". Archived from the original on 2019-03-10.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1959). "Recherches sur l'Empire du Mali au Moyen Age". Recherches Africaines (in French). Archived from the original on 2007-05-19.

- Sapong, Nana Yaw B. (2016-01-11). "Mali Empire". In Dalziel, Nigel; MacKenzie, John M. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe141. ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4.

- Thornton, John K. (2012-09-10). A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521727341.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Musa I of Mali. |

- 13th-century births

- 1330s deaths

- Mali Empire

- Mansas of Mali

- Guinean philanthropists

- Keita family

- 14th-century monarchs in Africa

- History of Mali

- African slave owners

- 14th-century travelers