Mao Anying

Mao Anying | |

|---|---|

Mao Anying in a Soviet officer's uniform | |

| Born | 24 November 1922 Changsha, Hunan, China |

| Died | 25 November 1950 (aged 28) Tongchang, North Pyongan, North Korea |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II Chinese Civil War Korean War † |

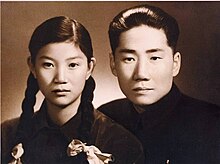

| Spouse(s) | Liu Songlin (m. 1949–1950) |

| Relations | Mao Zedong (father) Yang Kaihui (mother) |

Mao Anying (Chinese: 毛岸英; pinyin: Máo Ànyīng; 24 November 1922 – 25 November 1950) was the eldest son of Mao Zedong and Yang Kaihui.

Educated in Moscow and a veteran of multiple wars, Mao was killed in action by an air strike during the Korean War.

Early life[]

Mao was born at Central South University Xiangya Hospital in Changsha, Hunan Province. His mother, Yang Kaihui, second wife of Communist Leader Mao Zedong, was executed by the Kuomintang in 1930. He and his younger brother, Mao Anqing, escaped to Shanghai. Their father was in Jiangxi province at the time, and they were enrolled into the Datong Kindergarten, which was run covertly by the Chinese Communist Party for the children of CCP leaders and operated by Dong Jianwu (董健吾) under the alias "Pastor Wang".[1] In 1933, after the Kuomintang expulsion of the CCP from Jianxi Soviet, support for the Datong Kindergarten dried up and Mao and his brother ended up on the streets.

World War II[]

In 1936, Mao was located by Dong and Kang Sheng and taken to Moscow, where he was enrolled with his brother Anqing at Interdom in the Soviet Union under the name "Sergei Yun Fu". His stepmother, He Zizhen would join them there after being wounded in battle; despite the fact that Mao’s father had left his mother for He, Anying had a good relationship with her and his-half sister Li Min who joined them in 1941.[2]

During the Second World War, Anying successfully petitioned Joseph Stalin to allow him and his brother Anqing to join the Soviet Red Army. Mao graduated from the Frunze Military Academy and the Lenin Military-Political Academy in 1943 and served as an artillery officer for the 1st Belorussian Front in the fight against the Third Reich in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the final Battle of Berlin.[3][4]

In 1946, Mao returned to Yan'an, where he served under Kang Sheng in fighting against the Kuomintang and defeating them in the Shanxi Province, reaching the rank of Major General in the Peoples Liberation Army. Upon his return to Beijing, Mao became a Secretary and Translator for Li Kenong in the Intelligence Department of the CCP and also the Deputy Secretary of the CCP Branch for the Beijing General Machinery Factory.

Korean War and death[]

In June 1950, Mao requested to join the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) as an officer in the Korean War. PVA commander Peng Dehuai and other high-ranking officers, fearing Mao Zedong's reaction if his favorite son was to be killed in combat, had long opposed allowing Mao to join the PVA and tried to prevent him from entering. Mao Zedong overrode Peng, who allegedly shouted, "He is Mao Zedong's son. Why should it be anything else?" Peng instead had Mao assigned to himself as his secretary and Russian translator, under the pseudonym "Secretary Liu" at the PVA headquarters, located in caves near an old gold mining settlement in Tongchang County. This location offered excellent protection from UN air attacks and was far from the front lines of the war.[4][5] However, the safety was an illusion, as the airspace was completely controlled by the US Air Force.[6]

On the evening of 24 November, two United Nations (UN) aircraft, P-61s on a photo reconnaissance mission, were seen overhead.[7] According to multiple Chinese eyewitnesses, sometime between 10:00 am and noon on 25 November, four Douglas A-26 Invaders dropped napalm bombs in the area.[8][9] One of the bombs destroyed a makeshift building near the caves, killing Mao and another officer. Several conflicting reasons have been given as to why Mao was in the building, including suggestions that he was cooking food on a smoky stove[failed verification] in violation of Chinese Army regulations,[1][7][10] fetching documents, or sleeping late due to night duties,[8] which had led to him missing breakfast.[11] Another reason given was that due to the high amount of communications, being the PVA headquarters, the Americans were able to combine aerial reconnaissance with the direction of radio waves, to locate its location.[12]

His body was reportedly burnt beyond recognition and was only identifiable through a Soviet watch given to him by Joseph Stalin. Peng immediately reported Mao's death to the Central Military Commission, but Zhou Enlai ordered the CMC and Politburo not to inform Mao Zedong. It was only in January 1951, when Mao Zedong asked his personal secretary Ye Zilong to have Mao transferred back to China, that Ye inform him of the news. Mao had been buried in Pyongyang, in the Cemetery for the Heroes of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army. Some sources claim that Peng Dehuai's fall from grace after the Great Leap Forward and subsequent prosecution during the Cultural Revolution was connected to Mao Anying's death, for which Mao Zedong supposedly held Peng responsible.[citation needed]

Disputes regarding death[]

The only unit operating the A-26 in Korea at the time was the 3rd Bomb Group, of the United States Air Force (USAF). Some accounts have claimed, most likely incorrectly, that the pilot responsible was Captain G. B. Lipawsky of the South African Air Force.[13] However, the only aircraft flown by South African pilots in Korea was the Mustang fighter bomber, which was unlikely to have been mistaken for the larger, twin-engine A-26s.[8]

Some Chinese citizens who oppose Mao Zedong commemorate the anniversary of Mao Anying's death by eating egg fried rice; it is alleged that his preparation of that meal drew the attention of American bombers, contributing to his demise.[14] However, according to Chen Pu, who witnessed his death, he recalled that in the planning rooms he would've been in, there were no cooking facilities, no oil, no salt and no eggs, and if he were to be cooking, he would have to be in the kitchen.[6] Being designated to manage communications, Mao had to go to the planning room to send a telegram, reporting on the current situation was why he returned to the planning room.[15][16] Otherwise, the story had likely arose out of political discord of the 1970s in China.[17]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chairman Mao Zedong and General Mao Anying, Chinese Military Leaders of the Korean War

- ^ Oxana Vozhdaeva (4 October 2013). "How children of the world united at a Soviet school". BBC News. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

Mao's eldest son, Mao Anying, who was known in the home as Sergei Yun Fu.

- ^ Pathanothai, Sirin. The Dragon Pearl. Simon and Schuster. 1994. p 163.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "No Dynasty for China: How Mao's Son Was Killed in the Korea War". National Interest. 25 April 2020.

- ^ Kruschev, Nikita. Memoirs of Nikita Kruschev, Vol 2. Pennsylvania State University Press. 2006. p 98.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "参谋与毛岸英一同葬身火海 遗腹女身世被瞒46年_新闻中心_新浪网". news.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "彭德怀文革时被污有意害死毛岸英". Cul.sohu.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sebastien Roblin, 2017, "A U.S. Bombing Run in North Korea Wiped Out Mao Zedong's Dynasty" National Interest (7 May), (Access: 17 March 2018.)

- ^ 武立金 (2006). "第六章 血染大榆洞". 毛岸英在朝鲜战场 (in Chinese). 作家出版社. ISBN 978-7-5063-3717-5.

- ^ Nanchu, Xing Hang, Page 94, McFarland Press, 2003, In North Korea: an American travels through an imprisoned nation ISBN 0-7864-1691-2, ISBN 978-0-7864-1691-2

- ^ Yi ge zhen zheng di ren Peng Dehuai. Peng Dehuai zhuan ji bian xie zu, 彭徳怀传记编写组. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Ren min chu ban she. 1994. ISBN 7-01-002005-1. OCLC 33378849.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ "当代 中国 人物 传记" 丛书 编辑 部. (1993). Peng Dehuai zhuan [Biography of Peng Dehuai]. "Dang dai Zhongguo ren wu zhuan ji" cong shu bian ji bu, 《当代中国人物传记》丛书编辑部. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Dang dai Zhongguo chu ban she. ISBN 7-80092-102-6. OCLC 28982336.

- ^ 66年前的今天:波兰裔南非飞行员杀害毛岸英. 网易新闻. 25 November 2016 (22 March 2017). A translated excerpt: "G. B. Lipawsky ... accumulated more than 12,000 hours of flight in World War II and North Korea. On November 24th, 1950 ... he ... attacked the command post of the Volunteers using napalm bombs."

- ^ "Holiday of the Week: Chinese Thanksgiving". China Digital Times. 24 November 2016.

- ^ "目击者见证毛岸英牺牲真相". 文史参考. December 2011.

- ^ "戳破谣言、敬悼英魂:毛岸英烈士牺牲的历史真相_中国江苏网". jsnews.jschina.com.cn. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Fallen Heir: Mao Anying". Young Pioneer Tours. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- 1922 births

- 1950 deaths

- Children of national leaders

- Mao Zedong family

- Chinese people of World War II

- Chinese military personnel of the Korean War

- Soviet military personnel of World War II

- Chinese expatriates in the Soviet Union

- Chinese military personnel killed in the Korean War

- Frunze Military Academy alumni

- Deaths by airstrike

- People from Changsha

- People of the Republic of China