March to Reims

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| March to Reims | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Coronation of Charles VII in Reims (miniature from the Vigiles du roi Charles VII de Martial d'Auvergne, Paris, BnF, département of Manuscrits). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

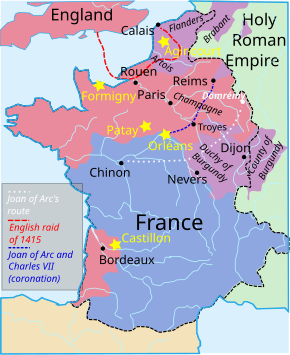

After the lifting of the Siege of Orléans and the decisive French victory at the Battle of Patay, the Anglo-Burgundian threat was ended. Joan of Arc convinced the Dauphin Charles to go to be crowned at Reims. The successful march of their army though the heart of territory held by the hostile Burgundians gave the throne of the French monarchy to Charles VII, who had been disinherited from it through the Treaty of Troyes.[2]

Background[]

Following the assassination of John the Fearless, the Treaty of Troyes in 1420 gave the throne of France to Henry V of England. Henry had married the daughter of King Charles VI of France, and his son Henry VI was to be his successor on the thrones of both France and England. But Henry V died in 1422 when his son was not yet one year old; the regency was entrusted to John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford. The intervention of Joan of Arc with the Dauphin Charles was seen as miraculous, even more so after the lifting of the Siege of Orléans and the Battle of Patay.

March to Reims[]

For the first time in the history of France, the eldest son of the king did not inherit the crown. Charles VI of France disinherited his son, leaving the kingdom of France to Henry VI of England, the son of his daughter Catherine. After Charles VI died, his son challenged his disinheritance and claimed the throne. Despite the French victory in the Battle of Patay on 18 June, which caused the English to retreat to Paris, the dauphin Charles VII refused to continue to Reims,[3] which was held by the Burgundians, and remained in Sully-sur-Loire then withdrew his army to Orléans intending to be crowned there, as was Louis VI.[4] Nevertheless, a coronation in Reims would have a much greater impact because it would be seen as a new miracle, attesting to his divine legitimacy.[5][6]

After initially meeting the Dauphin on 23 May 1429 at Loches, Joan of Arc next met him on 21 June at the Fleury Abbey to persuade him to go to Reims. The next day, the dauphin's council met in Châteauneuf-sur-Loire and ordered the army to gather at Gien.

On 24 June, preceded by her squire, , who held her banner emblazoned Jhésus Maria, Joan of Arc — arriving at Gien with her armor forged in Tours, her armor and sword of Fierbois — found Charles VII.[7] The next day 12000 men of the king's army gathered in Gien, bringing to 33000 the cavalry forces and 40000 foot-soldiers.[8] The French army took Bonny-sur-Loire[9] and Saint-Fargeau.

Joan of Arc broke her sword on the back of a camp follower. Two days later the Dauphin ordered a march to the city of the coronation: the march began at Gien on 29 June 1429. The ease of the march showed both the fragility of the Anglo-Burgundian rule and the restoration of confidence in the cause of Charles VII of France. According to Jean de Dunois,[10] bluffing was the only tactic that opened the gates of the city. The Marshal of France, Gilles de Rais, rode to Reims, hoping to use this victorious march to retrieve a ransom of land taken from "collaborators."[11]

Joan of Arc left Gien accompanied by her captains: , La Hire,[12] André of Lohéac, ,[13] Jean V de Bueil, Pierre Bessonneau, Jacques de Chabannes,[14] ,[15] Pierre Bessonneau, and Jean Poton de Xaintrailles.[16] On the road to Reims, the Constable Richemont sent to ask leave of the dauphin to serve at his coronation. Rostrenen accompanied the constable to Parthenay. During the march, the Burgundian garrison in Auxerre refused to open its gates. Georges de la Trémoille gave two thousand gold écus to the minister of the city; the city remained neutral and allowed the French army to resupply itself and to camp outside its walls on 1 and 2 July.[17] The army of the Dauphin left again; Saint-Florentin submitted immediately, as did Brienon l’Archevêque. On 4 July, the army reached Troyes, occupied by five or six hundred Burgundians, who refused to open the gates.

After four days of siege, the majority of the dauphin's council wanted to lift the siege and continue on the road without entering the city. On the fifth day of the siege, 9 July, Troyes capitulated (for fear of attack), but only Charles VII and the captains were able to enter. The soldiers spent the night in Saint-Phal, under the command of Ambroise de Loré. Gilles de Rais was one of the leaders of the army who reduced Troyes to obedience.[18]

Fewer than 2000 English soldiers[19] of the captain of Paris, John of Lancaster occupied Paris, which had as its provost Simon Morhier, and as Governor Jean de La Baume. Philip the Good of Burgundy opted to leave Laon for Paris, where he arrived on 10 July, appointed the Master of the Louvre Jean de Villiers de L'Isle-Adam governor, and committed to him the safety of Paris in the absence of Lancaster.[20] Philip sent ambassadors to the Dauphin Charles VII to sue for peace.

On 11 July the Dauphin's army left Troyes for the first time to head to Châlons-en-Champagne, which opened its gates on 14 July to let him spend the night.[21]

On Saturday 16 July, in the morning, Philip the Good left Paris to return to Laon, while the Archbishop of Reims, Regnault de Chartres, left Reims in the hands of William, Lord of Châtillon-sur-Marne and of the Sire de Saveuses; the dauphin arrived at the castle of the Archbishop of Reims in Sept-Saulx (located 21 km from Reims).[22] The dauphin summoned the people of Reims to open their gates, despite their vow to resist him for six weeks until the arrival of relief by Lancaster and Philip the Good.[23] After negotiations and dinner, Charles VII entered and slept in Reims. That same day, René of Anjou brought homage from Lorraine and Barrois to the Dauphin.

Consequences[]

On Sunday 17 July 1429 Charles VII was crowned King of France in Reims:[24] he received the Holy Ampulla from the hands of the Archbishop Renault Chartres.

"Noble King, now is executed the pleasure of God who wished I lift the siege of Orléans, and I bring you into this city of Rheims to receive your holy coronation to show you are the true king, and the one to whom the kingdom of France must belong," declared Joan of Arc, paying tribute to her king.

The coronation ceremony, given the circumstances, took place in simplicity, because the crown, the scepter, and the globe, were still in Saint-Denis, which was controlled by the English; among the peers, only three of the spiritual peers attended the ceremony: the Archbishop of Reims Renault Chartres, the Bishop of Laon William of Champeaux, the bishop of Châlons Jean Saarbrücken. But the essential rite was performed: the eighth sacrament (anointing of the king), which makes kings and which marks the sacred sign of legitimate power, was then given to Charles VII, making him the rightful monarch, representing the House of Valois, authentically appointed by God, against John of Lancaster, whom enemy arms had imposed, and against the irresponsible signature of a mad king.

Commemoration[]

For the fifth centennial of the campaign, and in the context of the canonization of Joan of Arc, a series of plaques was mounted on the route that Joan followed to retake Reims and crown the king.

Montmirail,

and Reims.

Bibliography[]

- Bouzy, Olivier (2013). Jeanne d'Arc en son siècle [Joan of Arc in her Century] (in French). Paris: Fayard. p. 317. ISBN 978-2-213-67205-2.

- Contamine, Philippe; Bouzy, Olivier; Hélary, Xavier (2012). Jeanne d'Arc. Histoire et dictionnaire [Joan of Arc: History and Dictionary]. Bouquins (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. p. 1214. ISBN 978-2-221-10929-8.

- DeVries, Kelly (1999). Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. p. 242. ISBN 0-7509-1805-5.

- Lurie, Guy (August 2015). "Citizenship in Late Medieval Champagne: The Towns of Châlons, Reims, and Troyes, 1417–circa 1435". French Historical Studies. 38 (3): 365. doi:10.1215/00161071-2884627..

Footnotes[]

- ^ d’après d’autre source il semble ne pas avoir participé http://jean-claude.colrat.pagesperso-orange.fr/1lafayette.htm

- ^ https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803105904481 treaty of Troyes], Oxford Reference}}

- ^ Jeanne d'Arc, Histoire et Dictionnaire, Philippe Contamine (Ed.), Robert Laffont, 2012, p.610

- ^ François Eudes de Mézeray, Histoire de France, Éditions H&D., p.140, 1839

- ^ Wavrin, ibid. Monstrelet, ch. LXI. P. Cochon, p 455

- ^ Biographie Didot: Falstalf. Registre du conseil dans Procès, v. IV, p. 452

- ^ Michel Tissier, Société Historique et Archéologique de Gien, Jeanne d’Arc et Gien (partie 2)has (Joan of Arc and Gien part 2), [larep.fr La République du Centre]

- ^ "Lettre d'Alain Chartier" [Letter from Alain Chartier]. stejeannedarc.net. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Jeanne d'Arc - Association des Villes Johanniques". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Jean le Bâtard d'Orléans (futur Dunois)". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ François Macé, Gilles de Rais, Centre régional de documentation pédagogique de Nantes, 1988, p.99.

- ^ "Étienne de Vignolles dit La Hire". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ http://www.guerre-de-cent-ans.com/personnages-divers.php

- ^ "I Jacques de Chabannes". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Jacques de Dinan seigneur de Beaumanoir". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Poton de Xaintrailles". pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Jeanne d'Arc (1429 - 1431)". histoire-fr.com. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Enguerrand de Monstrelet, La chronique d'Enguerran de Monstrelet, en deux livres, avec pièces justificatives, 1400-1444 (The Chronicle of Enguerran de Monstrelet, in two books, with supporting documents), published by , volume 4, 1860, p.337

- ^ Pierre Larousse, , volume 12

- ^ Michel Félibien, Histoire de la ville de Paris (History of the City of Paris), published by éditions Guillaume Desprez et Jean Desessartz, p.1599, 1725

- ^ "La chronique de Morosini". stejeannedarc.net.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access-death=ignored (help) - ^ Gabriel Daniel, Histoire de France depuis l'établissement de la monarchie française dans les Gaules, p.74, 1775

- ^ "Chronique des Cordeliers de Paris - folio 486". stejeannedarc.net. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Charles VII, Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1429 in Europe

- 1420s in France

- Battles of the Hundred Years' War

- Conflicts in 1429

- Henry VI of England