Mass of the Lord's Supper

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

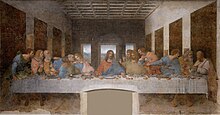

The Mass of the Lord's Supper, also known as A Service of Worship for Maundy Thursday, is a Holy Week service celebrated on the evening of Maundy Thursday.[1][2] It inaugurates the Easter Triduum,[3] and commemorates the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples, more explicitly than other celebrations of the Mass.

The Catholic Church, Lutheran Churches, Methodist Churches, Reformed Churches, and Anglican Communion celebrate the Mass of the Lord's Supper (or the Liturgy of Maundy Thursday).[1][4][5]

The Mass stresses three aspects of that event: "the institution of the Eucharist, the institution of the ministerial priesthood, and the commandment of brotherly love that Jesus gave after washing the feet of his disciples."[6]

In Anglicanism, these rites are found in the Book of Common Prayer,[7] as well as in the Anglican Missal.[8] In Methodism, they are found in the Book of Worship for Church and Home and The United Methodist Book of Worship. In Lutheranism, the Maundy Thursday liturgy is found in the Lutheran Service Book and Evangelical Lutheran Worship.

History[]

The celebration of a Mass in the evening of Holy Thursday began in late fourth-century Jerusalem, where it became customary to celebrate the events of the Passion of Jesus in the places where they took place. In Rome at that time a Mass was celebrated at which penitents were reconciled with a view to participation in the Easter celebrations. The Jerusalem custom spread and in seventh-century Rome the Pope celebrated a Mass of the Lord's Supper on this day as well as the Mass of Reconciliation. By the eighth century, the Masses became three: one for reconciliation, one for blessing the holy oils and a third for the Last Supper. The last two were in reduced form, being without Liturgy of the Word. Pope Pius V's reforms in 1570 forbade the celebration of Mass after noon, and the Mass of the Lord's Supper became a morning Mass and remained so until Pope Pius XII's reforms in the 1950s.[9]

The washing of feet that is now part of the Mass of the Lord's Supper was in use at an early stage without relation to this particular day, and was first prescribed for use on Holy Thursday by a 694 Council of Toledo. By the twelfth century it was found in the Roman liturgy as a separate service. Pope Pius V included this rite in his Roman Missal, placing it after the text of the Mass of the Lord's Supper.[10] He did not make it part of the Mass, but indicated that it was to take place "at a suitable hour" after the stripping of the altars.[11] The 1955 revision by Pope Pius XII inserted it into the Mass. Current rubrics indicate that the rite is not an obligatory part of that Mass, but rather is something to be carried out "where a pastoral reason suggests it" (Roman Missal, Mass of the Lord's Supper, no. 10).[12]

Structure[]

The Mass begins as usual, with the exception that the tabernacle, wherever placed, should be empty.[13]

In the 1962 Missal (Roman rite), although white vestments and the Gloria in Excelsis are used, this is still Passiontide, so the "Judica me" is omitted at the foot of the altar, the "Gloria Patri" in the Introit and at the end of the Lavabo is omitted, and the Preface of the Cross is used. (The crucifixes, which have been covered during Passiontide, can today be covered with white instead of with violet.)

At the singing of the Gloria in Excelsis Deo, all the church bells may be rung; afterwards, they (along with the organ) are silenced until the Gloria of the Easter Vigil.[14]

The Liturgy of the Word consists of the following readings:

- Exodus 12:1-8, 11-14, a description of the original Passover celebration.

- Psalm 115 (116), thanksgiving for being saved

- Corinthians 11:23-26, Paul the Apostle's account of what Jesus did at his Last Supper

- John 13:1-15, John the Evangelist's account of how Jesus washed his disciples' feet before that meal as an example of how they should treat each other.

After the homily, which should explain the three aspects of the celebration mentioned above,[15] the priest who is celebrating the Mass removes his chasuble, puts on a linen gremiale (an amice is often used for this purpose), and proceeds to wash the feet of a number of people (usually twelve, corresponding to the number of the Apostles)[16]

The recitation of the Nicene Creed is omitted in Anglican, Methodist, Lutheran, and Roman Catholic liturgies for Maundy Thursday.[17]

There are special formulas in the Eucharistic Prayer to recall that the Mass of the Lord's Supper is in commemoration of Jesus' Last Supper.

Sufficient hosts are consecrated for the faithful to receive Communion both at that Mass and on the next day, Good Friday. The hosts intended for the Good Friday service are not placed in the tabernacle, as is usual, but are left on the altar, while the priest says the postcommunion prayer.[18] Then the priest incenses the Blessed Sacrament three times and, taking a humeral veil with which to hold it, carries it in solemn procession to a place of reservation somewhere in the church or in an appropriately adorned chapel.[19] The procession is led by a cross-bearer accompanied by two servers with lit candles; other servers with lit candles follow and a thurifer immediately precedes the priest.[20]

On arrival at the altar of repose, the priest places the vessel with the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle there, leaving the door open. He then incenses it and closes the tabernacle door. After a period of adoration, he and the servers depart in silence.[21] A plenary indulgence is granted to the faithful, who devoutly recite the Tantum Ergo on Holy Thursday if it is recited in a solemn manner.[22]

The continuation of Eucharistic adoration is encouraged, but if continued after midnight should be done without outward solemnity.[23][24] In the Philippines and several other Catholic countries, the faithful will travel from church to church praying at each church's altar of repose in a practice known as Seven Churches Visitation or Visita Iglesia. The Blessed Sacrament remains in the temporary place until the Holy Communion part of the Good Friday liturgical service.

Stripping of the Altar[]

On Maundy Thursday, the chancels of churches are traditionally stripped, with the altar often being draped with black paraments, in preparation for Good Friday.[25]

In the Methodist Churches, the chancel is stripped of any decorations, such as flowers and candles.[26] Aside from depictions of the Stations of the Cross, other images, such as the cross, continue to be veiled in black or purple.[26]

At the conclusion of the Maundy Thursday liturgy in Lutheran Churches, "the altar, lectern and pulpit are left bare until Easter to symbolize the humiliation and barrenness of the cross."[27]

In Anglican Churches, this ceremony is also performed at the conclusion of Maundy Thursday services, "in which all appointments, linens, and paraments are removed from the altar and chancel in preparation for Good Friday."[28]

In the Catholic Church, the form of the Roman Rite in use before 1955 had no washing of the feet, which could instead be done in a separate later ceremony, and the Mass concluded with a ritual stripping of all altars, except the altar of repose, but leaving the cross and candlesticks.[29] This was done to the accompaniment of Psalm 21 (Vulgate) (Deus, Deus meus) preceded and followed by the antiphon "Diviserunt sibi vestimenta mea: et super vestem meam miserunt sortem" (They divided my clothes among them and cast lots for my garment).[30] In the Catholic Church, since 1955, the altar is stripped bare without ceremony later.[31]

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mass of the Lord's Supper. |

- ^ a b "A Service of Worship for Maundy Thursday" (PDF). Cheatham Memorial United Methodist Church. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Elwell, Walter A. (2001). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academic. p. 750. ISBN 9780801020759.

Observed in the Roman Catholic Church, Maundy Thursday appears on the Lutheran, Anglican, and many Reformed liturgical calendars and is almost universally celebrated with the Lord's Supper.

- ^ "General Norms for the Liturgical Year and the Calendar, 19". Archived from the original on 2009-04-11. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ "The Liturgy of Maundy Thursday". Holy Trinity Lutheran Church. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Maundy Thursday". Reformed Church in America. 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 45

- ^ Proper Liturgy for Maundy Thursday, 1979 (American) Book of Common Prayer

- ^ The Anglican Missal, pp. B44-B59

- ^ Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff, An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies (Liturgical Press, 2007 ISBN 0-8146-5856-3, ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7), p. 379

- ^ Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff, An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies (Liturgical Press, 2007 ISBN 0-8146-5856-3, ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7), p. 380

- ^ Missale Romanum, Editio Princeps (1570), reproduction published by Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1998, ISBN 88-209-2547-8

- ^ "Holy Thursday Mandatum", USCCB, 2016

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 48

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 50

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 45

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 51

- ^ Jr., J. Dudley Weaver (2002). Presbyterian Worship: A Guide for Clergy. Geneva Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780664502188.

Some congregations in some traditions omit the creed in the Maundy Thursday liturgy because it is thought of as being too festive for the occasion. The Roman, Lutheran, Episcopalian, and Methodist liturgies all omit the creed.

- ^ Missale Romanum, Feria V in Cena Domini, 35-36

- ^ Missale Romanum, Feria V in Cena Domini, 37-38

- ^ Missale Romanum, Feria V in Cena Domini, 38

- ^ Missale Romanum, Feria V in Cena Domini, 39-40

- ^ Sacred Apostolic Penitentiary, Enchiridion Indulgentiarum, 2nd ed., 1968

- ^ Missale Romanum, Feria V in Cena Domini, 43

- ^ Holy Thursday Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, 56

- ^ The Century Dictionary. Century Company. 1911. p. 2378.

The early church observed it as a strict fast; in the church services doxologies were omitted, no music except the most plaintive was allowed, and the altars were stripped and draped in black.

- ^ a b Hickman, Hoyt L. (1 July 2011). United Methodist Altars: A Guide for the Congregation (Revised Edition). Abingdon Press. p. 55. ISBN 9781426730696.

- ^ Fakes, Dennis R. (1994). Exploring Our Lutheran Liturgy. CSS Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 9781556735967.

- ^ Publishing, Morehouse (2015). The Episcopal Handbook, Revised Edition. Church Publishing, Inc. p. 218. ISBN 9780819229564.

stripping of the altar: Ceremony at the conclusion of the Maundy Thursday liturgy, in which all appointments, linens, and paraments are removed from the altar and chancel in preparation for Good Friday.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Roman Missal, Thursday of the Lord's Supper, 41

- Catholic liturgy

- Holy Week