Megatheriidae

| Megatheriidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eremotherium skeleton, NMNH, Washington, DC. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Suborder: | Folivora |

| Family: | †Megatheriidae J. E. Gray 1821 |

| Type genus | |

| †Megatherium | |

| Subfamilies | |

|

See text | |

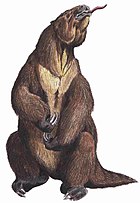

Megatheriidae is a family of extinct ground sloths that lived from approximately 23 mya—11,000 years ago.[1]

Megatheriids appeared during the Late Oligocene (Deseadan in the SALMA classification), some 23 million years ago, in South America. The group includes the heavily built Megatherium (given its name 'great beast' by Georges Cuvier[2]) and Eremotherium. An early megatheriid, the more slightly built Hapalops, reached a length of about 1.2 metres (3.9 ft). The nothrotheres have recently been placed in their own family, Nothrotheriidae.[3]

The skeletal structure of these ground sloths indicates that the animals were massive. Their thick bones and even thicker joints (especially those on the hind legs) gave their appendages tremendous power that, combined with their size and fearsome claws, provided a formidable defense against predators.

The earliest megatheriid in North America was Eremotherium eomigrans which arrived 2.2 million years ago, after crossing the recently formed Panamanian land bridge. At more than five tons in weight, 6 meters in length, and able to reach as high as 17 feet (5.2 m), it was taller than an African bush elephant bull. Unlike relatives, this species retained a plesiomorphic extra claw. While other species of Eremotherium had four fingers with only two or three claws, E. eomigrans had five fingers, four of them with claws up to nearly a foot long.[4]

Classification[]

Proschismotherium Family †Megatheriidae Gray 1821

- Subfamily †

- Tribe †

- Subtribe †

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †Prepotherium

- Subtribe †

- Genus †

- Genus †Promegatherium

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †Megatherium

- Genus †Eremotherium

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Subtribe †

- Tribe †

- ?Subfamily †[5]

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †Hapalops

- Genus †Pelecyodon

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †

- Genus †

- ?Subfamily †Thalassocninae[6][7]

- Genus †Thalassocnus

Phylogeny[]

The following sloth family phylogenetic tree is based on collagen and mitochondrial DNA sequence data (see Fig. 4 of Presslee et al., 2019).[8]

| Folivora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[]

- ^ Paleobiology Database: Megatheriidae

- ^ G. Cuvier (1796)

- ^ Muizon, C. de; McDonald, H. G.; Salas, R.; Urbina, M. (June 2004). "The Youngest Species of the Aquatic Sloth Thalassocnus and a Reassessment of the Relationships of the Nothrothere Sloths (Mammalia: Xenarthra)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 387–397. doi:10.1671/2429a. S2CID 83732878. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ De Iuliis and Cartelle (1999)

- ^ However, a phylogenetic study conducted by Amson, de Muizon & Gaudin (2017) indicates that at least the genera Schismotherium, Pelecyodon, Analcimorphus and Hapaloides do not belong to the family Megatheriidae, or even to the group Megatheria (containing the families Megatheriidae and Nothrotheriidae). See: Eli Amson; Christian de Muizon; Timothy J. Gaudin (2017). "A reappraisal of the phylogeny of the Megatheria (Mammalia: Tardigrada), with an emphasis on the relationships of the Thalassocninae, the marine sloths" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 179 (1): 217–236. doi:10.1111/zoj.12450.

- ^ Eli Amson; Christian de Muizon; Timothy J. Gaudin (2017). "A reappraisal of the phylogeny of the Megatheria (Mammalia: Tardigrada), with an emphasis on the relationships of the Thalassocninae, the marine sloths" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 179 (1): 217–236. doi:10.1111/zoj.12450.

- ^ Varela, L.; Tambusso, P.S.; McDonald, H.G.; Fariña, R.A.; Fieldman, M. (2019). "Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis". Systematic Biology. 68 (2): 204–218. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy058. PMID 30239971.

- ^ Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

External links[]

Data related to Megatheriidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Megatheriidae at Wikispecies- CTD: Megatheriidae

- Memidex: Megatheriidae

- Prehistoric sloths

- Prehistoric mammal families

- Oligocene xenarthrans

- Miocene xenarthrans

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Rupelian first appearances

- Pleistocene extinctions

- Paleogene mammals of South America

- Neogene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of North America

- Taxa named by John Edward Gray