Melchior Lorck

Melchior Lorck (or: or: or: Lorch) (1526/27 – after 1583 in Copenhagen) was a renaissance painter, draughtsman, and printmaker of Danish-German origin. He produced the most thorough visual record of the life and customs of Turkey in the 16th century, to this day a unique source. He was also the first Danish artist of whom a substantial biography is reconstructable and a substantial body of artworks is attributable.

Youth and early training[]

Melchior Lorck was born in either 1526 or 1527 as son of a city clerk, Thomas Lorck, in Flensburg in the duchy of Schleswig in present-day Germany.[1] The first document relating to him is the receipt of a royal Danish 4 year travel stipend from the Danish king, Christian III, signed on March 22, 1549 in Flensburg.[2] His earliest engravings stem from the years before the travel stipend, starting with rather unsecure copies after Heinrich Aldegrever, but soon developing a fine control of the burin as in the staunchly anti-papal The Pope as a Wild Man from 1545 and the Portrait of Martin Luther from 1548.[3] With the royal travel stipend Lorck went to southern Germany, settling in Nuremberg around 1550, where he paid tribute to that city's preeminent artist of the previous generation, Albrecht Dürer in a portrait print building on Hans Schwarz' portrait medal of the artist.

After a visit in Rome in 1551 and what seems to have been a short period of employment at the residence of count palatine Otto Henry in Neuburg an der Donau he worked for the circle of the prominent Fugger family in Augsburg, thereby drawing nearer to the imperial Habsburg family.

The years in Turkey[]

In 1555 Lorck was assigned to the embassy that the German king Ferdinand I (from 1556 Holy Roman Emperor) sent to the so-called Sublime Porte, the court of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in Constantinople (Istanbul). The aim of the embassy was to negotiate a settlement over Hungary over which both parties claimed supremacy. After the Ottomans had defeated the Hungarian army in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, where King Louis II of Hungary died,[4] the so-called Little War in Hungary, part of the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, had been raging, with the Ottomans holding the upper hand most of the time.

The embassy, which finally led to a cease-fire in 1562, was led by Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, is renowned for record of it found in the 'Turkish Letters' by Busbecq, published in 1581–1588 in Antwerp. Of the three and a half years that Lorck spent in the Turkish capital, approximately one and a half were spent with the rest of the entourage in confinement at the caravanserai where the Germans had been installed.

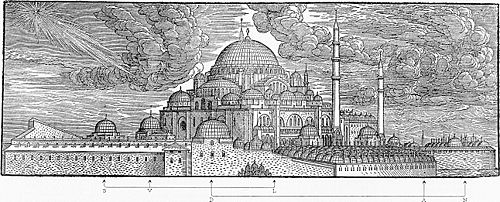

In 1555 at the caravanserai, the Elçi Hanı, Lorck produced engraved portraits of Busbecq and his co-envoys, Ferenc Zay and Antun Vrančić (Antonius Verantius), a few drawings of animals and a view over the rooftops of the city from one of the top windows of the lodging. In the periods of greater freedom however, he drew ancient and modern monuments of the city as well as the customs and dresses of the various peoples gathered from all parts of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of his sojourn, he must have been spending extensive time with the Turkish military, as he was later able to portray a large number of different ranks and nationalities in the Ottoman army.

Imperial employment[]

Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, Department of Prints and Drawings, inv. no. KKSgb6141

Lorck returned to Western Europe in the autumn of 1559. In 1560 he is documented in Vienna, where he stayed until 1566. His drawings of antique monuments of Constantinople and surroundings date from these years. The Arcadius Column, the pedestal of Theodosius the Great's obelisk on the hippodrome and the pedestal of Constantine's Column both represent monuments that are lost today. The monumental , seen from across the Golden Horn at Galata / Pera was also made at this time. This drawing, 1145 centimeters long and 45 centimeters high, drawn on twenty-one sheets, executed in brown and black ink with some watercolor, teeming with detail, is considered to be one of the hallmarks of early topographic drawing. It also contains the earliest self-portrait of the artist. See the Constantinople Prospect in Leiden's University Library.

While in Vienna, Melchior Lorck was contacted both by the brother of the late king Christian III, duke Hans the Elder of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev who demanded his service. Lorck responded willingly, but was eager to excuse himself for being too busy. While finally answering the duke in January 1563, he also sent King Frederik II a letter, containing a lengthy description of his career up to the date.[5] In 1562 Melchior Lorck had produced the large engraved of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and the Persian envoy in Constantinople, Ismaïl, which he added to his letters. In the letters, Melchior Lorck asked for funding, which effected a gracious royal gift of 200 Danish rigsdaler, to be handed over to him via his brother, , who had himself recently stepped into the king's service in Copenhagen.

Soon after he had written to both lords in January 1563, new assignments kept him busy however, and he remained in Vienna for another five years. In 1562, the son of Ferdinand I, Maximilian, had been elected King of the Romans (i.e. emperor-to-be) in Frankfurt am Main, and had since been travelling down the Danube to receive the homage of the cities, with a final stop in Vienna, which prepared itself for a grandiose entry to receive him in March 1563. Melchior Lorck was put in charge of the setting, which meant redressing of both the city itself, with triumphal arches, wine wells and tree-lined streets and of the inhabitants, dressed i Habsburg colours, varying from rank to rank and occupation to occupation.[6]

In 1564, on February 22, the emperor confirmed the alleged noble status of both Melchior Lorck and his three brothers, Caspar, Balthasar, and , citing in the elevation document Melchior's Turkish sojourn as the main argument for the elevation. Around the same time, Lorck was employed as Hartschier (from Italian: arciere), an honorary position with an annual salary in the horse guard of the emperor that he would keep until 1579.

In 1566, he followed the emperor in a campaign in Hungary that would eventually see the death of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent during the Battle of Szigetvár.

In December that year the emperor, Maximilian, wrote a rather unusual letter to his “cousin” (i.e. cousin in office), King Frederik II, asking him to receive Melchior Lorck well, as Lorck was to go to Denmark to collect the inheritance after his eldest brother, Caspar, who had been killed in the Northern Seven Years' War between Denmark and Sweden. The letter also demanded the king to let him return to the emperors service, thus foreboding any claim that the king would have on Lorck.[7]

As Melchior travelled north, however, he appears only to have come as far as Flensburg, before making his way south again.[8]

In Hamburg[]

In 1567 Melchior Lorck turns up in documents from the council of the city of Hamburg, and seems to remain there at least until 1572, when he draws up his last will and testament in that city.[9] Initially, Lorck was employed as cartographer, mapping the lower streams of the river Elbe, from Geesthacht to the sea, in order to support Hamburg's legal claims to the stable rights in a dispute with its neighbor Brunswick-Lüneburg. The magnificent map resulting from this commission is still in the possession of the State Archives of Hamburg today, where it remains one of the most precious holdings.[10]

Another important commission for the city was the rebuilding of the city gate (demolished), which was begun in 1568 and finished in 1570.[11]

While in Hamburg, Lorck published the turcophobic pamphlet Ein Liedt vom Türcken und Anti-Christ (A Song on the Turk and Antichrist), quite different in tone from his later, more neutrally descriptive renderings of the Turks.

In Lorck's testament, one of the only glimpses of a family life shines through as he leaves everything to a certain widow, Anna Schrivers, whom he describes as his betrothed bride. She is never heard of again.

Last Lorck was heard of in Hamburg was after his sojourn in Antwerp when in 1574 he finally received his salary and reimbursement for the [12] and where in 1575 he was called to witness at the Reichskammergericht in a case about the proper belonging of the area east of Hamburg called Vierlande and drew a map to document his statement.[13]

In Antwerp[]

In 1574 Lorck was found in Antwerp, where he seems to have been since 1573. He was one of the first to write an entry into the album amicorum of Abraham Ortelius, and befriended the publisher and engraver Philip Galle, who dedicated Hans Vredeman de Vries’s book about wells and fountains to him.[14] And he worked for the printing press of Christophe Plantin (woodblocks after his design are still found in the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp).

Laudatory remarks in the Civitates orbis terrarum of Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg[15] as well as the portrait of the antiquarian Hubert Goltzius, brother of Hendrik Goltzius, point to the network he was able to establish during his stay in the city. The turbulence of the Dutch Revolt made him leave the city in the summer of 1574, as his letter to Ortelius from October implies.[16]

Antwerp was the most promising of Lorck's stations in life, as he was here in one of the most important humanist centres of Europe, due to the prolific publishing houses, with Plantin's as the most important. A bronze medal to his honour was struck there by Steven van Herwijck (now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna). And he published his only more substantial book, the Soldan Soleyman Tvrckhischen Khaysers, vnd auch Furst Ismaelis auß Persien, Whare vnd eigendtliche contrafectung vnd bildtnuß (i.e. The True and Real Counterfeits and Pictures of the Turkish Emperor Sultan Süleyman and Prince Ismail from Persia), in April 1574. The book, the only known copy of which perished in the firestorms in Hamburg in June 1943, caused by the allied forces' Operation Gomorrha, contained two bust portraits and two full-length portraits of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and of the Persian envoy to the High Porte, Ismaïl, still known today, as well as accompanying poems by and Paulus Melissus. A lengthy announcement (quoted in 's dissertation from 1911[17]) of a book to come that would describe the entirety of Turkish society seemingly presaged the publication of the work underway of the so-called "Turkish Publication" (Wolgerissene und geschnittene Figuren...).

The Turkish Publication[]

Copenhagen, The Royal Library

While still employed as Hartschier Lorck proceeded with the idea of publishing a book on Turkey, as he promised in the Soldan Soleyman.... In a letter to the Danish king, Frederik II, of May 19, 1575,[18] he indicated that he had problems financing his publication and asked for economic support to this end. In the years from 1570 to this date, Lorck had managed to get a number of blocks for woodcuts cut after his drawings from Turkey (most likely in Antwerp). 12 woodcuts with motifs with architectural monuments are dated 1570, while 5 woodcuts with members of the Turkish army and its entourage are dated 1575. In the years to come this core would grow into a total of the 128 woodcuts that make up the Turkish Publication as we know it today.

Only a few preparatory drawings have come down to us, at least one suggesting that the entire range of planned motifs was somewhat larger than what we know of (i.e. the drawing with The Shooing of Oxen in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (inv. no. 38 225)).

The possible fate of the Turkish woodcuts[]

What happened to the artist as well as to the large stock of woodblocks for the publication by the time he disappears from the records in 1583, is not known. Two copies of a prototype title page for the publication exist, both initially from 1575, and each with an inserted title on top with the same text (Wolgerissene und geschnittene Figuren in Kupffer und Holz durch. Den Kunstreichen und weitberümten Melcher Lorch für die Mahler Bildthawer und Kunstliebenden. an tag gegeben) and the same date, but in different print type.[19] Whereas this 1619-edition never to have come into fruition, 7 years later the woodcuts were published in Hamburg, with the same title. It is therefore possible that the blocks had been in Hamburg ever since Lorck's death. The leading Lorck-scholar, Dr. Erik Fischer, the former keeper of the Copenhagen Printroom, suggests that the Turkish Publication came out only as a torso of what it was intended to be. In the re-publication of the woodcuts from 1646, a register of the motifs was attached, however it does not fit the prints and it points to an "original" where more can be learned. It is Dr. Fischer's thesis that that "original" was a written manuscript that would supplement the woodcuts and thus fulfil the promise given in the 1574 Soldan Soleyman... of a thorough description of Turkish society, life and customs. This idea is corroborated by the context in which the woodcuts are reused in another Hamburg-based publisher, Eberhard Werner Happel s bulletins on the Turkish wars of the 1680s and descriptions of Turkish society. Here, bits of descriptions turn up that, according to Dr. Fischer's thesis, could have been taken from a text very closely connected to the woodcuts and based on personal experience with the Turks, i.e. a text by Lorck himself.[20]

A ‘’Trachtenbuch’’ Project[]

A substantial number of drawings, the bulk of which was produced in the early 1570s, show individual figures and groups in their indigenous costumes. Lorck seems to have planned a book of costumes – a very popular genre in his day. The drawings, all inscribed with the region or city that they depict the costumes of, are all preparatory drawings for woodcuts, however, no such prints have come down to us, and the project remained unfinished.

Appointed to the Danish king[]

When Lorck had received his travel stipend from King Christian III in 1549, he promised to go away for four years only to return and step into the service of the king or his successor. He had not exactly kept that promise, always interrupted by more interesting prospects or more or less ill fortune. However, in 1578 he applied to the imperial court for a small fiefdom in Silesia, Guppern (unidentified).[21] When the application was dismissed by the emperor, now Rudolph II, he instead applied in 1579 for a pension and relief from duty as ‘’Hartschier’’, both granted graciously.[22]

On February 19, 1583 he turns up in the state account books of Denmark with the note “His Royal Majesty has, on February 19, 1580, employed Melcher Lorichs as a painter and counterfeiter”.[23]

His works for the king have been lost, if any substantial body of works was ever produced, which is doubtful. An engraved portrait of the king, a unique woodcut that seems to have meant as frontispiece to the rules for the Order of the Elephant, and a painted full-length portrait of king Frederik II, the first of its kind in Danish art, is all that survives today.

Apart from this, it appears Lorck spent most of his energy in having produced what amount to the bulk of the woodcuts for the ‘’Turkish Publication’’.

Last traces[]

On November 10, 1582 the king dismissed Lorck from service, stating only that his dismissal would be honourable if he returned his letter of appointment.[24] The last payment is recorded on March 4, 1583,[25] which is also the last certain source that he was still alive.[26]

Posthumous reception[]

Melchior Lorck was well known at the end of the 16th century and mentioned by e.g. Karel van Mander in the Schilder-boeck, even if he did not get a chapter of his own. And he continued to be mentioned in accounts of Flensburg as the city's famous son.

After the publication of the Turkish Publication in 1626, he inspired a number of artists and his renderings of the Turks became one of the standard references for the Western European view of the Turks. Both Nicolas Poussin and Stefano della Bella used the book for inspiration, and Rembrandt owned a copy of it.

Lorck is not widely known today, but often referred to in studies of the relationship between Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century and in oriental studies.

References[]

- ^ For the family history, see: Lorck-Schierning (1949); see also Wolfgang Müller's entry in Allgemeine deutsche Biographie & Neue deutsche Biographie, Vol. 15 (1987).

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1549 – March 22

- ^ On this print it says the artist was 21 years old when he created it, which is why one can extrapolate his approximate birth date.

- ^ Louis II of Hungary had been married to Mary of Austria, Queen of Hungary, a sister of Ferdinand I

- ^ Sometimes referred to as his autobiography, see: Fischer (1990) and Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), doc.no. 1563-January 1 for the full text.

- ^ Kayser (1979)

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), doc.no. 1566 - December 1.

- ^ It is likely that he met his other brother, the adventurous Andreas, in their hometown and learned how Andreas had just fallen steeply from favour, and perhaps realized that the name Lorck was not advantageous to flash at the Danish court. Anyway, Melchior turned south while his brother entered the service of the enemy and made the bad reputation of his name even worse.

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1572 – February 15

- ^ Lappenberg (1847); Bolland (1964)

- ^ The documents are reproduced in Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), document nos. 1570 – September 17, 1570 – October 22, and 1574 – August 30.

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), document no. 1574 – August 30

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), document no. 1575 – June 13; catalogue no. 1575,1.

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1574 – n.d. (a)

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1574 – n.d. (b)

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1574 – October 10

- ^ Harbeck (1911)

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2020), Document no. 1575 – May 19

- ^ One in the Städtisches Museum Flenburg, one in the Copenhagen Printroom Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ For the entire argument and a full treatment of the Turkish Publication with all the mentioned texts, as well as a facsimile reproduction of the 1626 reproduction, see Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010),Publication homepage

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-1010), Documents no. 1578 – March 7 (a)-(b) and Document no. 1579 – March

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-1010), Documents nos. 1579 – June 15, 1579 – July 9 (a)-(c) and 1579 – September 17

- ^ Document no. 1580 – February 19

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1582 – November 10

- ^ Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1583– March 4

- ^ A rather enigmatic payment record in 1588 from the empirical treasury in Vienna may be due to a slip of the pen, as Lorck is mentioned with all the other ‘’Hartschier’’s that had attended the funeral of Maximilian II in 1576 and were to be reimbursed for their mourning apparel 12 years earlier, see:Fischer, Bencard and Rasmussen (2009-2010), Document no. 1588 – December 31. Also, an attribution of a map of a part of the River Elbe from 1594 to Lorck cannot be confirmed today, as the map burned in the fire of Hamburg in 1842, see: Lappenberg (1847).

Bibliography[]

- The standard reference on the life and work of the artist is: Erik Fischer, Ernst Jonas Bencard and Mikael Bøgh Rasmussen, Melchior Lorck, Vol. 1-5, Vandkunsten Publishers and The Royal Library, Copenhagen 2009-1010. see: melchiorlorck.com

- Bolland, Jürgen: Die Hamburger Elbkarte von Melchior Lorichs. Mit einer Einleitung über den Zweck der Karte und die Tätigkeit von Melchior Lorichs in Hamburg, (Veröffentlichungen aus dem Staatsarchiv der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, vol. 8), Hamburg 1964

- Fischer, Erik: Melchior Lorck. Drawings from the Evelyn Collection at Stonor Park, England and from the Department of Prints and Drawings, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Copenhagen 1962

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Melchior Lorck. En dansk vagants levnedsløb i det 16. aarhundrede’, in: Fund og Forskning, XI, København 1964, pp. 33–72; summary in German, pp. 176–180. Online version

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Von weiteren Kopien nach Melchior Lorck nebst einem Exkurs über die Protoikonographie der Giraffe’, in: Nordelbingen, Band 43, Heide in Holstein 1974, pp. 81–92

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Melchior Lorck’, in: Biographisches Lexikon für Schleswig-Holstein und Lübeck, Band 6, Neumünster 1982, pp. 174–180

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Melchior Lorck’, in: Dansk Biografisk Leksikon, 3.udg., vol. 9, Copenhagen 1981, pp. 112–15; reprinted without the bibliography in Erik Fischer: Billedtekster, København 1988, pp. 11–18

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Ein Künstler am Bosporus: Melchior Lorch’, in: Sievernich, Gereon and Budde, Hendrik (eds.): Europa und der Orient, 800–1900, Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1989, pp. 794–798

- (Müller-Haas, Maria-Magdalena): Ein Künstler am Bosporus: Melchior Lorch (based on Erik Fischer's work), in; Sievenich, Gereon and Budde, Hendrik (eds.): Europa und der Orient, 800–1900. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh, 1989, pp. 241–244.

- Fischer, Erik: Melchior Lorck i Tyrkiet (Den kgl. Kobberstiksamling, Lommebog 49-50), København 1990; English translation of the text: Melchior Lorck in Turkey

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Danskeren Melchior Lorck som kejserlig tegner i 1550ernes Konstantinopel’, in: Folsach, K. von inter al. (eds.): Den Arabiske Rejse. Danske forbindelser med den islamiske verden gennem 1000 år, Århus 1996, pp. 30–43

- Fischer, Erik: ‘Melchior Lorck’, in: Weilbachs Kunstnerleksikon, vol. V, København 1996, pp. 152–154 Fischer, Erik: ‘Melchior Lorichs’, s.v., in: The Dictionary of Art, 19, 1996, pp. 661–663

- Harbeck, Hans: Melchior Lorichs : ein Beitrag zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte des 16. Jahrhunderts, Hamburg 1911.

- Ilg, Ulrike: ‘Stefano della Bella and Melchior Lorck: The Practical Use of an Artists’ Model Book’, in: Master Drawings, 14, no. 1, 2003, pp. 30–43

- Kayser, Werner: ‘Melchior Lorichs’ Ehrenpforten und Weinbrunnen zum Einzug Kaiser Maximilians II. in Wien, insbesondere die Ehrenpforte beim Waaghaus’, in: Philobiblion, vol. 23, 4, Hamburg 1979, pp. 279–295

- Lappenberg, Johann Martin: Die Elbkarte des Melchior Lorichs vom Jahre 1568, Hamburg 1847. Available at Google Books

- Lorck-Schierning, Andreas: Die Chronik der Familie Lorck, Neumünster 1949

- Poulsen, Hanne Kolind: ‘At brande Frederik 2. Om Melchior Lorcks kobberstik-portræt af Frederik 2.’, in: SMK Art Journal 2006, pp. 22–35. Available at smk.dk[permanent dead link]

- Rasmussen, Mikael Bøgh: ‘Melchior Lorck's Portrait of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1562): A Double-Coded View’, in: Andersen, Michael, Johannsen, Birgitte Bøggild and Johannsen, Hugo (eds.): Reframing the Danish Renaissance. Problems and Prospects in a European Perspective (Publications from the National Museum; Studies in Archaeology & History Vol. 16), Copenhagen, 2011, pp 165–170. Available at academia.edu

- St. Clair, Alexandrine: ‘A Forgotten Record of Turkish Exotica’, in: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, May 1969, New York, pp. 411–423

- Stichel, Rudolf H. W.: ‘Zum Postament der Porphyrsäule Konstantins de Grossen in Konstantinopel’, in: Istanbuler Mitteilungen, vol. 44, 1994, pp. 317–331

- Strzygowski, Josef: ‘Die Säule des Arkadius in Konstrantinopel’, in: Jarhrbuch des kaiserlich deutschen archäologischen Instituts, vol. 8, 1893, Berlin 1894, pp. 230–249

- Ward-Jackson, Peter: ‘Some rare Drawings by Melchior Lorichs in the collection of Mr. John Evelyn of Wotton and now at Stonor Park, Oxfordshire’, in: The Connoisseur, March 1955, London, pp. 83–93

- Yerasimos, Stéphane and Mango, Cyril: Melchior Lorichs’ Panorama of Istanbul 1559, Bern 1999

- Zijlma, Robert: Johan Leipolt to Melchior Lorck (Hollstein’s German Engravings, Etchings and Woodcuts 1400-1700, vol. 22), Amsterdam 1978.

External links[]

![]() Media related to Melchior Lorck at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Melchior Lorck at Wikimedia Commons

- Homepage for Erik Fischer's monograph and catalogue raisonné (2009-2010)]

- Melchior Lorck's works in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

- A German language article on the Map of the Elbe

- Melchior Lorck's works in the British Museum, London (beware - some are copies or inspired works, not autograph)

- 1646-edition of the Wolgerissene und geschnittene Figuren...

- 1520s births

- 1580s deaths

- 16th-century engravers

- 16th-century German painters

- German male painters

- Renaissance artists

- Danish engravers

- German engravers

- Danish painters

- German printmakers

- Renaissance engravers

- German Renaissance painters

- People from the Duchy of Schleswig

- People from Flensburg