Plantin-Moretus Museum

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

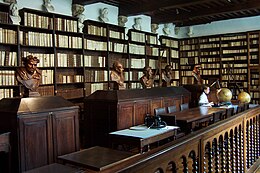

Library of Plantin Moretus Museum | |

| Location | Antwerp, Belgium |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iii), (iv), (vi) |

| Reference | 1185 |

| Inscription | 2005 (29th Session) |

| Area | 0.23 ha (0.57 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 184.1 ha (455 acres) |

| Website | www |

| Coordinates | 51°13′6″N 4°23′52″E / 51.21833°N 4.39778°ECoordinates: 51°13′6″N 4°23′52″E / 51.21833°N 4.39778°E |

Location of Plantin-Moretus Museum in Belgium | |

The Plantin-Moretus Museum (Dutch: Plantin-Moretusmuseum) is a printing museum in Antwerp, Belgium which focuses on the work of the 16th-century printers Christophe Plantin and Jan Moretus. It is located in their former residence and printing establishment, the Plantin Press, at the Vrijdagmarkt (Friday Market) in Antwerp, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2005.

History[]

The printing company was founded in the 16th century by Christophe Plantin, who obtained type from the leading typefounders of the day in Paris.[1] Plantin was a major figure in contemporary printing with interests in humanism; his eight-volume, multi-language Plantin Polyglot Bible with Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek and Syriac texts was one of the most complex productions of the period.[2] Plantin's is now suspected of being at least connected to members of heretical groups known as the Familists, and this may have led him to spend time in exile in his native France.[3][4]

After Plantin's death it was owned by his son-in-law Jan Moretus. While most printing concerns disposed of their collections of older type in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in response to changing tastes, the Plantin-Moretus company "piously preserved the collection of its founder."[5][6][7]

Four women ran the family-owned Plantin-Moretus printing house (Plantin Press) over the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries: Martina Plantin, Anna Goos, Anna Maria de Neuf and Maria Theresia Borrekens.[8]

In 1876 Edward Moretus sold the company to the city of Antwerp. One year later the public could visit the living areas and the printing presses. The collection has been used extensively for research, by historians H. D. L. Vervliet, Mike Parker and Harry Carter.[9] Carter's son Matthew would later describe this research as helping to demonstrate "that the finest collection of printing types made in typography's golden age was in perfect condition (some muddle aside) [along with] Plantin's accounts and inventories which names the cutters of his types."[10]

In 2002 the museum was nominated as UNESCO World Heritage Site and in 2005 was inscribed onto the World Heritage list.

The Plantin-Moretus Museum possesses an exceptional collection of typographical material.[11] Not only does it house the two oldest surviving printing presses in the world[citation needed] and complete sets of dies and matrices, it also has an extensive library, a richly decorated interior and the entire archives of the Plantin business, which were inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme Register in 2001 in recognition of their historical significance.[12]

Collection[]

- a Bible in five languages: Biblia Polyglotta (1568-1573)

- by Cornelis Kiliaan

- a geographical book: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum made by Abraham Ortelius

- a book describing herbs: made by Rembert Dodoens

- an anatomical book made by Andreas Vesalius and

- a book about decimal numbers from Simon Stevin

- a 36-line Bible

- paintings and drawings by Peter Paul Rubens

- the study of humanist Justus Lipsius and many of his works[13]

- some of the materials used by French type designer and printer Robert Granjon

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Uchelen, edited by Ton Croiset van; Dijstelberge, P. (2013). Dutch typography in the sixteenth century the collected works of Paul Valema Blouw. Leiden: Brill. p. 426. ISBN 9789004256552.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Harry Ransom Center Acquires Rare Plantin Polyglot Bible". University of Texas. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Bowen, Karen L.; Imhof, Dirk (2008). Christopher Plantin and Engraved Book Illustrations in Sixteenth-Century Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521852760.

- ^ Harris, Jason (2004). The Low Countries as a crossroads of religious beliefs ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. ISBN 9789004122888.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Caractères de l'Université". Type Foundry. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Garamond or Garamont". Type Foundry blog. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Warde, Beatrice (1926). "The 'Garamond' Types". The Fleuron: 131–179.

- ^ Plantin-Moretus Museum (2020-10-22). "Leading Ladies". Medium. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Carter, Harry (2002). A view of early typography up to about 1600 (Reprinted ed.). London: Hyphen. ISBN 9780907259213.

- ^ Drucker, Margaret Re ; essays by Johanna; Mosley, James (2003). Typographically speaking : the art of Matthew Carter (2. ed.). New York: Princeton Architectural. p. 33. ISBN 9781568984278.

- ^ Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Type Foundry. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Business Archives of the Officina Plantiniana". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ^ "The Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, Antwerpen".

Bibliography[]

- Voet, Leon (1969), The Golden Compasses: a history and evaluation of the printing and publishing activities of the Officina Plantiniana at Antwerp. Vol. 1, Christopher Plantin and the Moretuses: their lives and their world, Amsterdam: Vangendt & Co. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0710064667

- Voet, Leon; Kaye, Raymond H. (1972), The Golden Compasses: a history and evaluation of the printing and publishing activities of the Officina Plantiniana at Antwerp. Vol.2 The management of a printing and publishing house in Renaissance and Baroque, Amsterdam: Vangendt & Co. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0839000049

External links[]

![]() Media related to Paintings in the Museum Plantin-Moretus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings in the Museum Plantin-Moretus at Wikimedia Commons

- World Heritage Sites in Belgium

- Museums in Antwerp

- Printing press museums

- Biographical museums in Belgium

- Historic house museums in Belgium

- Houses in Belgium

- Museums established in 1877

- 1877 establishments in Belgium

- Art museums and galleries in Belgium