Mexican featherwork

Mexican featherwork, also called "plumería", was an important artistic and decorative technique in the pre-Hispanic and colonial periods in what is now Mexico. Although feathers have been prized and feather works created in other parts of the world, those done by the amanteca or feather work specialists impressed Spanish conquerors, leading to a creative exchange with Europe. Featherwork pieces took on European motifs in Mexico. Feathers and feather works became prized in Europe. The "golden age" for this technique as an art form was from just before the Spanish conquest to about a century afterwards. At the beginning of the 17th-century, it began a decline due to the death of the old masters, the disappearance of the birds that provide fine feathers and the depreciation of indigenous handiwork. Feather work, especially the creation of "mosaics" or "paintings" principally of religious images remained noted by Europeans until the 19th-century, but by the 20th-century, the little that remained had become a handcraft, despite efforts to revive it. Today, the most common feather objects are those made for traditional dance costumes, although mosaics are made in the state of Michoacán, and feather trimmed huipils are made in the state of Chiapas.

Mesoamerican featherwork[]

The use of feather for decorative purposes has been documented in many parts of the world in the past. In the New World, it is known to have had ceremonial use and ranking purposes, especially in attire in what are now Brazil and Peru.[1][2] In Mesoamerica, their use became highly developed with some of the most intricate examples coming from what is now central Mexico.[3] One reason for this was their symbolic and religious use.[4] Much of this symbolism arose with the spread of the worship of the Toltec god/king Quetzalcoatl, depicted as a serpent covered in quetzal feathers. Quetzalcoatl was said to have discovered gold, silver and precious stones. When he fled Tula, he released all kind of birds he was breeding.[3][5] The Aztec main god, Huitzilopochtli, is associated with the hummingbird. His origin is from ball of fine feathers that fell on his mother, Coatlicue, and impregnated her. He was born fully armed with an eagle feather shield, fine plumage in his head and on his left sandal.[6]

Feathers were valued similarly to jade and turquoise in Mesoamerica. They were considered to have magical properties as symbols of fertility, abundance, riches and power and those who used them were associated with divine powers.[7] Evidence of use goes back at least as far as the Mayas, with depictions of them on the murals at Bonampak. The Mayans also raised birds in part for feathers.[8][9] Toltec groups were making feathered items from black and white feathers of local origin.[5] The most developed use of feathers in Mesoamerica was among the Aztecs, Tlaxcaltecs and Purepecha.[1] Feathers were used to make many types of objects from arrows, fly whisks, fans, complicated headdresses and fine clothing.[10] By the reign of the Aztec ruler Ahuizotl, richer feathers from tropical areas came to the Aztec Empire with quetzal and the finest feathers used by Moctezuma's reign.[5] Feathers were used for ceremonial shields, and the garments of Aztec eagle warriors were completely covered in feathers. Feather work dressed idols and priests as well.[11] Moctezuma asked the Purépecha for help against the Spanish by sending gifts that included quetzal feathers. Among the Purépecha, feathers were used similarly, for ceremonial shields, bucklers, doublets for the cazonci or ruler and feather ceremonial garments for priests, warriors and generals. To declare war, the Purépecha showed enemies wood covered in feathers and send highly prized green feathers to allies and potential allies. Soldiers who died in war were buried with feathers.[12][13]

Feathers from local and faraway sources were used, especially in the Aztec Empire. The feathers were obtained from wild birds as well as from domesticated turkeys and ducks, with the finest feathers coming from Chiapas, Guatemala and Honduras .[14] These feathers were obtained through trade and tribute.[15] Feathers functioned as a kind of currency along with cocoa beans, and were a popular trade item because of their value and ease of transport over long distances and a close relationship developed between traders and feather workers.[16] Certain areas were required to pay tribute in raw feathers and other in finished feather goods, but no area was required to provide both.[17] Cuetzalan paid tribute to Moctezuma in the form of quetzal feathers. This demand was so great that it led to the local extinction of quetzals in that region, leaving only the name of a local tree, quetzalcuahuitl, where the birds used to hide to eat.[18]

The most important of feathers in central Mexico were the long green feathers of the resplendent quetzal which were reserved for deities and the emperor.[15] One reason for their rarity was that quetzals could not be domesticated as they died in captivity. Instead wild birds were caught, plucked and released.[19] Other tropical birds were used as well. Bernardino de Sahagún made a list of the species used for fine feathers, many of which are now either threatened or locally extinct. These include the mountain trogon, lovely cotinga, roseate spoonbill, squirrel cuckoo, red-legged honeycreeper, emerald toucanet, agami heron, russet-crowned motmot, turquoise-browed motmot, blue grosbeak, golden eagle, great egret, military macaw, scarlet macaw, yellow-headed amazon, Montezuma oropendola and the over 53 species of hummingbird found in Mexico.[20][21]

In Aztec society, the class that created feather objects was called the amanteca, named after the Amantla neighborhood in Tenochtitlan where they lived and worked.[9][22] The amanteca had their own god, Coyotlinahual, who had companions called , and . They also honored the female deities and .[23][24] Daughters of amanteca generally became embroiderers and feather dyers, with the boys dedicated to the making of feather objects.[23] The amanteca were a privileged class of craftsmen. They did not pay tribute nor were required to perform public service. They had a fair amount of autonomy in how they ran their businesses. Feather work was so highly prized that even sons of nobility learned something of it during their education.[25] The sophistication of this art can be seen in pieces created before the Conquest, some of which are part of the collection of the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, such as Montezuma's headdress, the ceremonial coat of arms and the great fan or fly whisk. Other important examples such as shields are in museums in Mexico City.[9]

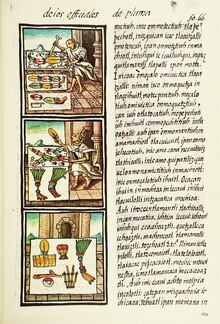

The Florentine Codex gives information about how feather works were created. The amantecas had two ways of creating their works. One was to secure the feathers in place using agave cord for three-dimensional objects such as fly whisks, fans, bracelets, headgear and other objects. The second and more difficult was a mosaic type technique, which the Spanish also called "feather painting." These were done principally on feather shields and cloaks for idols.[26][27] Feather mosaics were arrangements of minute fragments of feathers from a wide variety of birds, generally worked on a paper base, made from cotton and paste, then itself backed with amate paper, but bases of other types of paper and directly on amate were done as well.[28][29] These works were done in layers with "common" feathers, dyed feathers and precious feathers. First a model was made with lower quality feathers and the precious feathers found only on the top layer.[26][29] The adhesive for the feathers in the Mesoamerican period was made from orchid bulbs.[29]

Sometimes feathers were dyed, and sometimes fine lines or dots were painted on the feathers themselves.[30] In some of the most precious of Aztec art, feathers were combined with gold and precious stones.[31] Feather art needs to be protected from light, which fades the colors and from insects that eat them. Preservatives were made with several kinds of plants, but today commercial insecticides are used.[32]

One other way to use feathers was the creation of garments either decorated with feathers or with thread which was created by spinning cotton and feather shreds. The garments of eagle warriors were completely covered in feathers. Fabric made of the latter was favored by the nobility, both men and women which distinguished them from commoners.[4][11] Little is known how feathers were incorporated into fabric in the Mesoamerican period.[33] The only vestige of this practice is the making of wedding huipils in the town of Zinacantán in Chiapas. Although research has shown this practice is descended from the Mesoamerican one, it is still different. The Mesoamerican feathered cloth was made with thread made of cotton fiber and feathers done on a backstrap loom, which the current wedding huipils incorporate feathers into commercially spun cotton thread.[26][34]

European discovery of featherwork[]

When the Spanish arrived to Mexico, they were impressed with the bird species of the land and the use of feather, with Hernán Cortés receiving among his gifts feathers from Moctezuma.[11] As early as 1519, Cortés sent feathered shields, head adornments, and fans to Spain. In 1524, Diego de Soto returned to Spain from the New World. Among the gifts for King Charles V was artwork, including that made with feathers, such as shields with scenes of sacrifice, serpents, butterflies, birds and crests. In 1527, Cortés sent thirty eight pieces of what are identified as feather work to Asia.[28][35]

After the Conquest, the art of working with feathers survived, but on a lesser scale and its uses changed.[8] pagan ritual use ended with Christian evangelization, with some surviving works conveying Christian religious themes. Featherwork's use in war also remained. One type of feather work to remains strong was the creation of mosaics, many of which were created and sent to Europe, Guatemala and Peru.[36] They were even sent as far as Asia as gifts but little is known of this trade.[37] Exotic feathers themselves were exported to Europe and used to adorn hats, horses and clothing.[36]

The importance of feather work and the impression it made on the Spanish is documented by Spaniards such as Hernán Cortés, Francisco de Aguilar, Bartolomé de las Casas, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Francisco López de Gómara, Peter Martyr, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and Andres de Tapia .[38] Feathers add chromatic and luminous feathers difficult to create with paints, although oil painting at the time had well developed techniques to play with light.[31] Mexican expertise was valued as well. Even though there was feather art also made in Asia, it was not as valued in the 16th and 17th-century as that from Mexico.[39]

Featherwork with Christian themes[]

Feather work and the conquest led to a creative exchange from the conquest to about 1800.[40] Evangelism added Christian themes to feather work, including the making of ritual items.[38] Amantecas were creating Christian religious images within months after the arrival of the conquistadors, destined for Europe as well as Asia.[28] The first known Christian-inspired pictures in feather work were made for banners, on a cotton cloth with an imprimatur, on which the design was made. They had a backing of very fine palm or rush mats bound with twine or vegetable lianas.[29] The Huejotzingo Codex depicts the making of a feather and gold banner, the first indication of feather work with Christian images.[41]

At first, feather work was suppressed by the Spanish as part of their efforts to eradicate the old religion. However, they soon changed tactics and employed the feather workers to create Christian images. These new works are called "feather mosaics" because of the small pieces of feathers used, and most are in the Baroque style then favored, as the artists copied images brought from Spain.[42] After the Conquest, hummingbird feathers were used to adorn images of Christ in Michoacan, such as agave yarn sandals in hummingbird feathers made in Tzintzuntzan.[29][43] Indian craftsmen made and offered crosses and candlesticks adorned with green feathers called quezalli.[44] Small scale feather images and pendants serving as protective amulets were also made.[45]

The 16th-century mosaics were made with different sized feathers combined with paper strips. Over the years, the feathers became smaller, the compositions more harmonious and the designs more subtle with the additions of gold leaf, gold foil and colored brushwork. The basic imagery was European but the edging shows traces of pre Hispanic designs.[46] The iconography of feather art images focused on founders and patron saints, along with figures related to the various religious orders. These always followed the recommendations of the Council of Trent and often to the dominant style.[47] Feathered religious items were sent to Europe, including to several popes in Rome. A number of these were re-gifted to other nobles and for this reason can be found in various museums in various parts of Europe.[48] Feather work became a popular item in the collection of kings, emperors, nobles, clergy, intellectuals and naturalists from the 16th to 18th century, with pieces reaching courts in Prague, Abras Castle, El Escorial and various other cities in Europe. Some even went as far as China, Japan and Mozambique.[28]

In addition to the images, feathers were used to adorn priests' clothing such as chasubles, rain capes and miters. They also made feather decorations for church altars and convents.[42] Feathered miters and other vestments were sent and gifted to European bishops, especially in southern Europe and were used while conducting Mass.[28] Although there are no written records to indicate that this use of feathered vestments were a result of Mexican influence, they did not appear until after the mid 16th-century.[49] European engravings were used as a model for feather images created for miters which today can be still found in Milan, Florence and New York. However, these and other Christian images were not exact copies of the prints as elements from several prints were combined and even pre Hispanic motifs appeared in some. These miters served as an innovation in the pictoral language of the church as the vestments themselves added a kind of power through their magnificence.[50]

Monastery schools in Mexico, especially those run by the Franciscans and Augustinians, taught feather work, especially the creation of feather mosaics.[42][51] The skills of these artists remained important initially, even able to reproduce Latin calligraphy. One important example of this is "Sacras de Ambras" at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Here, black feathers are pasted over a ribbon of small white feathers.[47] One particularly notable area of colonial feather working was in Patzcauaro, Michoacán. These workers maintained many of the ancient privileges of pre Hispanic feather workers.[52]

Mesoamerican feather work inspired European works such as the Libro di piume (The Feather Book) by Dionisio Minaggio, the gardener to the governor of Milan, who learned the technique and created reproductions of birds in his regions, as well as portraits of the actors of the Commedia dell'arte.[53] Other artists such as Tommaso Ghisi and Jacopo Ligozzi used the technique as well to create works for the collections of the Medicis, Aldrovandi, Settala and Rudolf II of Prague.[40] Ulisse Aldrovandi described the creation of feather mosaics as a "threshold between art and science."[54]

Featherwork 1600-1900[]

The "golden age" of Mexican feather work lasted until the very beginning of the 17th-century, when it declined because the old masters disappeared. At this time, demand for the work declined as well, because the Spanish began to disdain indigenous handcrafts and oil painting became preferred for the production of religious images.[38][55]

In the 17th-century, imagery done in feather work became more varied, including the Virgin of Guadalupe and those from European mythology, especially on fans for ladies.[56][57] Techniques changed to include a profusion of paper strips on mosaics, replacing the earlier use of gold trimmings.[58] One image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is completely of feathers. While she is clothed in the usual way, the image lacks many of the decorations and symbols that are now standard. This may indicate that this is one of the first copies of the image.[57] Another important 17th-century piece depicts the Assumption of Mary, now in the Museum of the Americas in Madrid .[59]

More modification of the technique occurred in the 18th century, perhaps because it was no longer done only by the indigenous. Feather work was supplemented with the use of oil paint to depict people (especially faces and hands), landscapes and animals and tiny strips of paper were dropped along with the outer borders.[58][60]

By the nineteenth century, the craft all but disappeared with only some limited activity in Michoacán. Many were done with cheap, dyed feathers, smaller works with little artistic value.[55] They, however, still attracted attention from visitors to Mexico. In 1803, Alexander von Humboldt visited Pátzcuaro and both a feather image of Our Lady of Health, which is now in a German museum. Her hands and face are in oil but the rest is in hummingbird feathers.[58] Count Beltrani traveled in Mexico in 1830 and mentioned Michoacan feather work in his journals, obtaining two mosaics. Frances Calderon de la Barca, with of the first Spanish ambassador to Mexico, noted that the mosaics of saints and angels were crude in drawing but exquisite in coloring.[61]

The nuns at the Santa Rosa Convent in Puebla were noted for their feather work in the 19th-century, with several notable works still in existence.[61] In the mid 19th-century, lithography was introduced in Mexico and some prints were used as bases for feather work, which were then backed with sheet metal. In Puebla, this was a popular technique for folk figures such as the China Poblana.[62] The last innovation in the craft was the use of photographs. One such work used a photograph of Juan Arriaga de Yturbe done by Monico Guzman Alvarez of Patzcuaro, done in 1895.[63]

Featherwork 1900-2000[]

By the 20th-century, feather work existed as a handcraft, rather than as art. One reason for this was that the disappearance of many bird species has led to a lack of fine feathers.[64] In the first half of the century feather work images were almost exclusively of postcards or other informal forms, with images of cockfights or birds made with dyed chicken or turkey feathers. Manuel Gamio tried to revive feather work's artistic nature. In 1920 he designed and supervised the creation of two mural panels, one with an Aztec serpent and the other with a Mayan serpent, copied from archeological pieces. It was done on black silk with quetzal feathers, gold, silver and silk threads. However, the fate of these works is not known.[64]

Similarly, garments made with feathers have also almost completely disappeared. The only vestige of this is the wedding huipil made by the Tzotzils in Zinacatlan, Chiapas. However, these have the feathers added to commercially made cotton thread, anchored to it as decoration. Thread spun with feathers is no longer made.[65] One other notable piece was a reproduction of the "Montezuma headdress" made for the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.[55]

In the latter 20th-century, a number of artists tried to bring back the technique as an art form. Painter and tapestry weaver Carmen Padin began researching the technique after hearing Fernando Gamboa lament its loss. From 1979 to 1981, she exhibited her work in various cities of Mexico which included robes, capes, shields and collages. However, she had to stop by the 1990s because of the difficulty of obtaining feathers.[64] Josefina Ortega Salcedo became attracted to the technique after reading about it in the Artes de México magazine. She studied drawing and painting at the Academy of San Carlos with the goal of applying them to feather work. Her most valuable work in this medium includes several portraits, copied from photographs with precision. Her images are placed on a base of light-colored feathers with the images arranged using crepe paper cut outs and colored feathers. However, she, too, no longer works with this technique.[66] Those who still continue to work with it include Elena Sanchez Garrido, who combines feather work and watercolors, and Tita Bilbaro who makes Aztec and modern style images using feathers, sand, fabric, leather, mirrors an sea shells. In the late 1980s she exhibited her work in Mexico City and several places in northern Mexico.[67]

One notable family that continues the technique as a handcraft is the Olay family. This tradition began when Gabriel Olay traveled with a mule train and hunted birds during his wanderings. Then an indigenous person taught him the basics of feather working. He developed his craft then passed it onto his children and grandchildren. Most of the family works on reproductions of pre Hispanic images. Son Gabriel Olay Olay has created a large body of work in the technique and lives in Tlalpujahua, Michoacan. Four of his pieces are part of the collection of the Morelia Cultural Center and others in various museums in the state of Michoacan. His image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was given by Mexican president Luis Echeverría to Pope John XXIII and is part of the Vatican's collection. Grandson Hans Matias Olay specializes in reproducing the birds and flowers that the Nahuas in Guerrero paint on amate paper. In 1990, the National Museum of Anthropology held an exhibit of works by Gabriel Olay Ramos and his sisters Gloria and Esperanza. Olay Ramos lives in Mexico City and mostly uses rooster and hen feathers dyed in different colors. The Olays try to maintain as much of the pre Hispanic technique as possible, avoiding peacock and pheasant feathers as they are not native to Mexico. They use Campeche wax to affix the feathers and amate paper as the backing.[68]

Other workers with feathers include Juan Carlos Ortiz of Puebla who also creates feather mosaics, Jorge Castillo of Taxco who combines silver and feathers.[69]

The most common use of feathers in modern Mexico is in the creation of traditional dance costumes. These include the headdresses for dances such as the Quetzales in Puebla and the Concheros performed in various parts of central Mexico. In Oaxaca, there is the Dance of the Feather, which used dyed ostrich feathers and for the Dance of Calala, in Suchiapa, Chiapas, the main dancer uses a fan of turkey and rooster feathers. Ostrich feathers are the most common in traditional dance costumes, followed by rooster, turkey and hen feathers. Despite their bright color, peacock feathers are rarely used. In most cases, the symbolic meaning of the feathers has been forgotten. One notable exception is the Huichols, who have maintained much of their original cosmology.[70]

Notable featherwork pieces[]

Despite its popularity from in the late Mesoamerican period into the early colonial period, few vestiges with this technique survive into the 21st-century.[71] One reason for this is the care needed to maintain the pieces. It is important to know the characteristics of each type of feather to use and preserve them correctly. The best feathers to use are those that have been molted, as they have less organic materials and less likely to deteriorate. A feather object can last indefinitely if it is preserved in a hermetically sealed case of inert gas, with a fixed humidity, darkness and low temperature. However, this renders the piece unobservable. These objects can be exhibited in galleries, museums and private collections with minimal decay if temperature and humidity are controlled and light kept to a minimum.[10]

Perhaps the best known piece is the so-called Montezuma's headdress. Despite its name, research has proven that it was not worn by the Aztec emperor. It was most likely made for an image as it looks like the one for Quetzalcoatl depicted in the Codex Magliabechiano. The original is in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna. A replica made with authentic techniques was made for the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.[27]

Because of the sending of many fine feather mosaics to Europe, a number of important pieces are located in museums and other collections on that continent. The oldest feather piece created by Christian indigenous workers is the Misa de San Gregorio at the Museum of the Jacobins in Auch, France. It was commissioned by Diego de Huanitzin, a converted member of Moctezuma's family and Pedro de Gante. It was probably made by artisans from San Jose de Belen de los Naturales. It is dated 1539 and given as a gift to Pope Paul III by Antonio de Mendoza, according to the inscription, following the papal bull that declared the indigenous to be endowed with reason and able to fully participate in Catholic rites. It is probably the piece never made it to the Pope and its interim fate is unknown. However, it was rediscovered in 1987, when a second-hand clothes dealer took it to auction in Paris.[45][72] Another notable work is from the 19th-century called San Lucas pintando a la Virgen, located in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. It is attributed to painter Juan Correa. The clothing is done in feathers but the face and hands were done in oil.[73]

However, a number of important feather mosaic pieces remain in Mexico. San Pedro is a work from the 16th-century, found at the archbishopric of Puebla and shows Roman influence in the style.[74] Another piece in Puebla is a portrait of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, who protected the Indians in Puebla.[75] La Piedad is from the 17th-century at the Franz Mayer Museum. It depicts Mary with Jesus dead on her lap.[59] Another piece in this museum is the Virgen del Rosario, from the 17th-century, with the imagery of the Rosary important to counter Islam and Protestantism.[76] One important 16th-century image is Salvator Mundi at the Museum of Tepotzotlan. It shows influence from Byzantine iconography including Asian features. In the four corners there are Cyrillic characters repeated that have not been deciphered. The inscription FILIUS appears on the right when it should be on the left.[45][74]

No examples of pre Conquest feather fabric survive, and only a few survive from the colonial period.[77] Important cloths of this type include two mantles from San Miguel Zinacantepec, the Huipil of La Malinche at the Museum of Anthropology, the Tlamachayatl at the Ethnographic and Historical Museum in Rome and the Paño Novohispano at the Museo Textil de Oaxaca.[78][79][80] All have feathers or feather pieces either embroidered onto or twisted into cotton. The Paño is a remnant of a huipil with feathers woven into the cloth, and is of a very similar design to the Malinche huipil.[81]

Church vestments, especially miters can be found in various collections in Europe including the Vatican. The church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome preserves two 18th century sets of vestments which were gifts from Mexico. These include two miters with a base of flax paper and silk with white feathers glued onto it. Against this background are small pieces of paper sewn on, then with colored feathers glued to these to form floral wreath patterns.[82]

Notes[]

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 18

- ^ Meneses, p. 22

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 17

- ^ a b Meneses, p. 19

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 33

- ^ Russo, p. 3

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 27

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 82

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 19

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 238

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 20

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 143

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 81

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 27, 35

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 35

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 33–36

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 65

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 196–196

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 28

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 207

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 235

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 14

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 56

- ^ Meneses, p. 18

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 57

- ^ a b c Russo, p. 25

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 70

- ^ a b c d e Russo, p. 5

- ^ a b c d e Castello Yturbide, p. 202

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 203

- ^ a b Russo, p. 27

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 202–203

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 77

- ^ Meneses, p. 88

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 11

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 40

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 104

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 12

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 103

- ^ a b Russo, p. 6

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 186

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 21

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 145

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 175

- ^ a b c Russo, p. 17

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 207-208

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 125

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 21-22

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 160

- ^ Russo, p. 19-20

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 152

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 147–152

- ^ Russo, pp. 5–6

- ^ Russo, p. 14

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 22

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 200

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 128

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 208

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 130

- ^ Russo, p. 29

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 209

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 213

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 214

- ^ a b c Castello Yturbide, p. 221

- ^ Meneses, pp. 25–26

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 222

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 225

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 222–223

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 226

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 227

- ^ Meneses, p. 11

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 118–119

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 138

- ^ a b Castello Yturbide, p. 120

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 126

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 135

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 85

- ^ Meneses, pp. 11–12

- ^ Castello Yturbide, pp. 88–89

- ^ Meneses, p. 24

- ^ Meneses, p. 12-14

- ^ Castello Yturbide, p. 98

Bibliography[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mexican feather art. |

- Castello Yturbide, Teresa (1993). The Art of Featherwork in Mexico. Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex. ISBN 968 7009 37 3.

- Meneses Lozano, Hector Manuel (2008). Un paño novohispano, tesoro del arte plumaria (in Spanish). Mexico City: Apoyo al Desarrollo de Archivos y Bibliotecas de Mexico, A.C. ISBN 978 968 9068 44 0.

- Russo, Alessandra (2011). El Vuelo de las imágenes: Arte Plumario en México y Europa/Images Take Flight: Feather Art in Mexico and Europe. Gerhard Wolf and Diana Fane. Mexico City: Museo Nacional de Arte/Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. ISBN 978 607 605 044 6.

- Arts in Mexico

- Featherwork

- Mesoamerican art