Moctezuma II

| Moctezuma

Xocoyotzin | |

|---|---|

| De Facto Ruler of the Aztec Triple Alliance | |

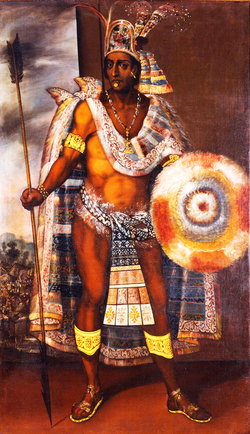

"The Emperor Moctezuma", belonging to the work "The discovery and conquest of the new world : containing the life and voyages of Christopher Columbus", published in the United States in 1892. | |

| 9th tlatoani of Tenochtitlan | |

| Reign | 1502 or 1503–1520 |

| Predecessor | Ahuitzotl |

| Successor | Cuitláhuac |

| Born | c. 1466 |

| Died | June 29, 1520 (aged 53–54) Tenochtitlan, Mexico |

| Consort | Teotlalco Tlapalizquixochtzin |

| Issue | Isabel Moctezuma Pedro Moctezuma Mariana Leonor Moctezuma Chimalpopoca Tlaltecatzin |

| Father | Axayacatl |

| Mother | |

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin (c. 1466 – 29 June 1520) [moteːkʷˈsoːma ʃoːkoˈjoːtsin] ![]() modern Nahuatl pronunciation (help·info)),[N.B. 1] variant spellings include Motecuhzomatzin, Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma, Motēuczōmah, Muteczuma, and referred to retroactively in European sources as Moctezuma II, was the ninth Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan and the sixth Huey Tlatoani or Emperor of the Aztec Empire, reigning from 1502 or 1503 to 1520. The first contact between the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica and Europeans took place during his reign, and he was killed during the initial stages of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, when conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men fought to take over the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. During his reign, the Aztec Empire reached its greatest size. Through warfare, Moctezuma expanded the territory as far south as Xoconosco in Chiapas and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and incorporated the Zapotec and Yopi people into the empire.[1] He changed the previous meritocratic system of social hierarchy and widened the divide between pipiltin (nobles) and macehualtin (commoners) by prohibiting commoners from working in the royal palaces.[1]

modern Nahuatl pronunciation (help·info)),[N.B. 1] variant spellings include Motecuhzomatzin, Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma, Motēuczōmah, Muteczuma, and referred to retroactively in European sources as Moctezuma II, was the ninth Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan and the sixth Huey Tlatoani or Emperor of the Aztec Empire, reigning from 1502 or 1503 to 1520. The first contact between the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica and Europeans took place during his reign, and he was killed during the initial stages of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, when conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men fought to take over the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. During his reign, the Aztec Empire reached its greatest size. Through warfare, Moctezuma expanded the territory as far south as Xoconosco in Chiapas and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and incorporated the Zapotec and Yopi people into the empire.[1] He changed the previous meritocratic system of social hierarchy and widened the divide between pipiltin (nobles) and macehualtin (commoners) by prohibiting commoners from working in the royal palaces.[1]

Though two other Aztec rulers succeeded Moctezuma after his death, their reigns were short-lived and the empire quickly collapsed under them. Historical portrayals of Moctezuma have mostly been colored by his role as ruler of a defeated nation, and many sources have described him as weak-willed, superstitious, and indecisive.[2] His story remains one of the most well-known conquest narratives from the history of European contact with Native Americans, and he has been mentioned or portrayed in numerous works of historical fiction and popular culture.

Name[]

The Nahuatl pronunciation of his name is [motekʷˈsoːma]. It is a compound of a noun meaning "lord" and a verb meaning "to frown in anger", and so is interpreted as "he is one who frowns like a lord"[3] or "he who is angry in a noble manner."[4] His , shown in the upper left corner of the image from the Codex Mendoza above, was composed of a diadem (xiuhuitzolli) on straight hair with an attached earspool, a separate nosepiece, and a speech scroll.[5]

Regnal number[]

The Aztecs did not use regnal numbers; they were given retroactively by historians to more easily distinguish him from the first Moctezuma, referred to as Moctezuma I.[2] The Aztec chronicles called him Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, while the first was called Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina or Huehuemotecuhzoma ("Old Moctezuma"). Xocoyotzin (IPA: [ʃokoˈjotsin]) means "honored young one" (from "xocoyotl" [younger son] + suffix "-tzin" added to nouns or personal names when speaking about them with deference[6]).

Coronation[]

The year in which Moctezuma was crowned is uncertain. Most historians suggest the year of 1502 to be most likely, though some have argued in favor of the year 1503. A work currently held at the Art Institute of Chicago known as the Stone of the Five Suns is an inscription written in stone representing the Five Suns and a date in the Aztec calendar, 1 crocodile 11 reed, which is the equivalent to 15 July 1503 in the Gregorian calendar. Some historians believe this to be the exact date in which the coronation took place.[7] However, most documents say Moctezuma's coronation happened in the year 1502, and therefore most historians believe this to have been the actual date.[8]

Reign[]

After his coronation he set up thirty-eight more provincial divisions, largely to centralize the empire. He sent out bureaucrats, accompanied by military garrisons. They made sure tax was being paid, national laws were being upheld, and served as local judges in case of disagreement.[9]

Contact with the Spanish[]

First interactions with the Spanish[]

In 1517, Moctezuma received the first reports of Europeans landing on the east coast of his empire; this was the expedition of Juan de Grijalva who had landed on San Juan de Ulúa, which although within Totonac territory was under the auspices of the Aztec Empire. Moctezuma ordered that he be kept informed of any new sightings of foreigners at the coast and posted extra watch guards to accomplish this.[10]

When Cortés arrived in 1519, Moctezuma was immediately informed and he sent emissaries to meet the newcomers; one of them was an Aztec noble named Tentlil in the Nahuatl language but referred to in the writings of Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo as "Tendile". As the Spaniards approached Tenochtitlán they made an alliance with the Tlaxcalteca, who were enemies of the Aztec Triple Alliance, and they helped instigate revolt in many towns under Aztec dominion. Moctezuma was aware of this and sent gifts to the Spaniards, probably in order to show his superiority to the Spaniards and Tlaxcalteca.[11]

On 8 November 1519, Moctezuma met Cortés on the causeway leading into Tenochtitlán and the two leaders exchanged gifts. Moctezuma gave Cortés the gift of an Aztec calendar, one disc of crafted gold and another of silver. Cortés later melted these down for their monetary value.[12]

According to Cortés, Moctezuma immediately volunteered to cede his entire realm to Charles V, King of Spain. Though some indigenous accounts written in the 1550s partly support this notion, it is still unbelievable for several reasons. As Aztec rulers spoke an overly polite language that needed translation for his subjects to understand, it is difficult to find out what Moctezuma really said. According to an indigenous account, he said to Cortés: "You have come to sit on your seat of authority, which I have kept for a while for you, where I have been in charge for you, for your agents the rulers..." However, these words might be a polite expression that was meant to convey the exact opposite meaning, which was common in Nahua culture; Moctezuma might actually have intended these words to assert his own stature and multigenerational legitimacy. Also, according to Spanish law, the king had no right to demand that foreign peoples become his subjects, but he had every right to bring rebels to heel. Therefore, to give the Spanish the necessary legitimacy to wage war against the indigenous people, Cortés might just have said what the Spanish king needed to hear.[13]

Host and prisoner of the Spaniards[]

Moctezuma brought Cortés to his palace where the Spaniards lived as his guests for several months. Moctezuma continued to govern his empire and even undertook conquests of new territory during the Spaniards' stay at Tenochtitlán.[citation needed]

At some time during that period, Moctezuma became a prisoner in his own house. Exactly why this happened is not clear from the extant sources. The Aztec nobility reportedly became increasingly displeased with the large Spanish army staying in Tenochtitlán, and Moctezuma told Cortés that it would be best if they left. Shortly thereafter, Cortés left to fight Pánfilo de Narváez, who had landed in Mexico to arrest Cortés. During his absence, tensions between Spaniards and Aztecs exploded into the Massacre in the Great Temple, and Moctezuma became a hostage used by the Spaniards to ensure their security.[N.B. 2]

Death[]

In the subsequent battles with the Spaniards after Cortés' return, Moctezuma was killed. The details of his death are unknown, with different versions of his demise given by different sources.

In his Historia, Bernal Díaz del Castillo states that on 29 June 1520, the Spanish forced Moctezuma to appear on the balcony of his palace, appealing to his countrymen to retreat. Four leaders of the Aztec army met with Moctezuma to talk, urging their countrymen to cease their constant firing upon the stronghold for a time. Díaz states: "Many of the Mexican Chieftains and Captains knew him well and at once ordered their people to be silent and not to discharge darts, stones or arrows, and four of them reached a spot where Montezuma could speak to them."[14]

Díaz alleges that the Aztecs informed Moctezuma that a relative of his had risen to the throne and ordered their attack to continue until all of the Spanish were annihilated, but expressed remorse at Moctezuma's captivity and stated that they intended to revere him even more if they could rescue him. Regardless of the earlier orders to hold fire, however, the discussion between Moctezuma and the Aztec leaders was immediately followed by an outbreak of violence. The Aztecs, disgusted by the actions of their leader, renounced Moctezuma and named his brother Cuitláhuac tlatoani in his place. In an effort to pacify his people, and undoubtedly pressured by the Spanish, Moctezuma was struck dead by a rock.[15] Díaz gives this account:

"They had hardly finished this speech when suddenly such a shower of stones and darts were discharged that (our men who were shielding him having neglected for a moment their duty, because they saw how the attack ceased while he spoke to them) he was hit by three stones, one on the head, another on the arm and another on the leg, and although they begged him to have the wounds dressed and to take food, and spoke kind words to him about it, he would not. Indeed, when we least expected it, they came to say that he was dead."[16]

Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún recorded two versions of the conquest of Mexico from the Tenochtitlán-Tlatelolco viewpoint. In Book 12 of the twelve-volume Florentine Codex, the account in Spanish and Nahuatl is accompanied by illustrations by natives. One is of the death of Moctezuma II, which the indigenous assert was due to the Spaniards. According to the Codex, the bodies of Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin were cast out of the Palace by the Spanish; the body of Moctezuma was gathered up and cremated at .

Aftermath[]

The Spaniards were forced to flee the city and they took refuge in Tlaxcala, and signed a treaty with the natives there to conquer Tenochtitlán, offering to the Tlaxcalans control of Tenochtitlán and freedom from any kind of tribute.[17]

Moctezuma was then succeeded by his brother Cuitláhuac, who died shortly after during a smallpox epidemic. He was succeeded by his adolescent nephew, Cuauhtémoc. During the siege of the city, the sons of Moctezuma were murdered by the Aztecs, possibly because they wanted to surrender. By the following year, the Aztec Empire had fallen to an army of Spanish and their Native American allies, primarily Tlaxcalans, who were traditional enemies of the Aztecs.

Contemporary depictions[]

Bernal Díaz del Castillo[]

|

| Aztec civilization |

|---|

| Aztec society |

| Aztec history |

The firsthand account of Bernal Díaz del Castillo's True History of the Conquest of New Spain paints a portrait of a noble leader who struggles to maintain order in his kingdom after he is taken prisoner by Hernán Cortés. In his first description of Moctezuma, Díaz del Castillo writes:

The Great Montezuma was about forty years old, of good height, well proportioned, spare and slight, and not very dark, though of the usual Indian complexion. He did not wear his hair long but just over his ears, and he had a short black beard, well-shaped and thin. His face was rather long and cheerful, he had fine eyes, and in his appearance and manner could express geniality or, when necessary, a serious composure. He was very neat and clean, and took a bath every afternoon. He had many women as his mistresses, the daughters of chieftains, but two legitimate wives who were Caciques[N.B. 3] in their own right, and only some of his servants knew of it. He was quite free from sodomy. The clothes he wore one day he did not wear again till three or four days later. He had a guard of two hundred chieftains lodged in rooms beside his own, only some of whom were permitted to speak to him.[18]

When Moctezuma was allegedly killed by being stoned to death by his own people, "Cortés and all of us captains and soldiers wept for him, and there was no one among us that knew him and had dealings with him who did not mourn him as if he were our father, which was not surprising, since he was so good. It was stated that he had reigned for seventeen years, and was the best king they ever had in Mexico, and that he had personally triumphed in three wars against countries he had subjugated. I have spoken of the sorrow we all felt when we saw that Montezuma was dead. We even blamed the Mercedarian friar for not having persuaded him to become a Christian."[19]

Hernán Cortés[]

Unlike Bernal Díaz, who was recording his memories many years after the fact, Cortés wrote his Cartas de relación (Letters from Mexico) to justify his actions to the Spanish Crown. His prose is characterized by simple descriptions and explanations, along with frequent personal addresses to the King. In his Second Letter, Cortés describes his first encounter with Moctezuma thus:

Moctezuma [sic] came to greet us and with him some two hundred lords, all barefoot and dressed in a different costume, but also very rich in their way and more so than the others. They came in two columns, pressed very close to the walls of the street, which is very wide and beautiful and so straight that you can see from one end to the other. Moctezuma came down the middle of this street with two chiefs, one on his right hand and the other on his left. And they were all dressed alike except that Moctezuma wore sandals whereas the others went barefoot; and they held his arm on either side.[20]

Anthony Pagden and Eulalia Guzmán have pointed the Biblical messages that Cortés seems to ascribe to Moctezuma's retelling of the legend of Quetzalcoatl as a vengeful Messiah who would return to rule over the Mexica. Pagden has written that "There is no preconquest tradition which places Quetzalcoatl in this role, and it seems possible therefore that it was elaborated by Sahagún and Motolinía from informants who themselves had partially lost contact with their traditional tribal histories".[21][22]

Bernardino de Sahagún[]

The Florentine Codex, made by Bernardino de Sahagún, relied on native informants from Tlatelolco, and generally portrays Tlatelolco and Tlatelolcan rulers in a favorable light relative to those of Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma in particular is depicted unfavorably as a weak-willed, superstitious, and indulgent ruler.[23] Historian James Lockhart suggests that the people needed to have a scapegoat for the Aztec defeat, and Moctezuma naturally fell into that role.[24]

Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc[]

Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, who may have written the Crónica Mexicayotl, was possibly a grandson of Moctezuma II. It is possible that his chronicle relates mostly the genealogy of the Aztec rulers. He described Moctezuma's issue and estimates them to be nineteen – eleven sons and eight daughters.[25]

Depiction in early post-conquest literature[]

Some of the Aztec stories about Moctezuma describe him as being fearful of the Spanish newcomers, and some sources, such as the Florentine Codex, comment that the Aztecs believed the Spaniards to be gods and Cortés to be the returned god Quetzalcoatl. The veracity of this claim is difficult to ascertain, though some recent ethnohistorians specialising in early Spanish/Nahua relations have discarded it as post-conquest mythicalisation.[26]

Much of the idea of Cortés being seen as a deity can be traced back to the Florentine Codex, written some 50 years after the conquest. In the codex's description of the first meeting between Moctezuma and Cortés, the Aztec ruler is described as giving a prepared speech in classical oratorical Nahuatl, a speech which as described verbatim in the codex (written by Sahagún's Tlatelolcan informants) included such prostrate declarations of divine or near-divine admiration as, "You have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached your water, your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your mat, your throne, which I have briefly kept for you, I who used to keep it for you," and, "You have graciously arrived, you have known pain, you have known weariness, now come on earth, take your rest, enter into your palace, rest your limbs; may our lords come on earth." While some historians such as Warren H. Carroll consider this as evidence that Moctezuma was at least open to the possibility that the Spaniards were divinely sent based on the Quetzalcoatl legend, others such as Matthew Restall argue that Moctezuma politely offering his throne to Cortés (if indeed he did ever give the speech as reported) may well have been meant as the exact opposite of what it was taken to mean, as politeness in Aztec culture was a way to assert dominance and show superiority.[27] Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans believed the conquistadors to be gods, most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta.[28] Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled the Florentine Codex, was also a Franciscan priest.

Indigenous accounts of omens and Moctezuma's beliefs[]

Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590) includes in Book 12 of the Florentine Codex eight events said to have occurred prior to the arrival of the Spanish. These were purportedly interpreted as signs of a possible disaster, e.g. a comet, the burning of a temple, a crying ghostly woman, and others. Some speculate that the Aztecs were particularly susceptible to such ideas of doom and disaster because the particular year in which the Spanish arrived coincided with a "tying of years" ceremony at the end of a 52-year cycle in the Aztec calendar, which in Aztec belief was linked to changes, rebirth, and dangerous events. The belief of the Aztecs being rendered passive by their own superstition is referred to by Matthew Restall as part of "The Myth of Native Desolation" to which he dedicates chapter 6 in his book Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest.[29] These legends are likely a part of the post-conquest rationalization by the Aztecs of their defeat, and serve to show Moctezuma as indecisive, vain, and superstitious, and ultimately the cause of the fall of the Aztec Empire.[24]

Ethnohistorian Susan Gillespie has argued that the Nahua understanding of history as repeating itself in cycles also led to a subsequent rationalization of the events of the conquests. In this interpretation the description of Moctezuma, the final ruler of the Aztec Empire prior to the Spanish conquest, was tailored to fit the role of earlier rulers of ending dynasties—for example Quetzalcoatl, the mythical last ruler of the Toltecs.[30] In any case it is within the realm of possibility that the description of Moctezuma in post-conquest sources was colored by his role as a monumental closing figure of Aztec history.[citation needed]

Legacy[]

Wives, concubines, and children[]

Moctezuma had numerous wives and concubines by whom he fathered an enormous family, but only two women held the position of queen – Tlapalizquixochtzin and Teotlalco. His partnership with Tlapalizquixochtzin also made him a king consort of Ecatepec since she was queen of that city.

Of his many wives may be named the princesses Teitlalco, Acatlan, and Miahuaxochitl, of whom the first named appears to have been the only legitimate consort. By her he left a son, Asupacaci, who fell during the Noche Triste, and a daughter, Tecuichpoch, later baptized as Isabel Moctezuma. By the Princess Acatlan were left two daughters, baptized as Maria and Mariana (also known as Leonor);[31] the latter alone left offspring, from whom descends the Sotelo-Montezuma family.[32]

Though the exact number of his children is unknown and the names of most of them have been lost to history, according to a Spanish chronicler, by the time he was taken captive, Moctezuma had fathered 100 children and fifty of his wives and concubines were then in some stage of pregnancy, though this estimate may have been exaggerated.[33] As Aztec culture made class distinctions between the children of senior wives, lesser wives, and concubines, not all of his children were considered equal in nobility or inheritance rights. Among his many children were Princess Isabel Moctezuma, Princess Mariana Leonor Moctezuma [34] and sons Chimalpopoca (not to be confused with the previous huey tlatoani) and Tlaltecatzin.[35]

Descendants in Mexico and the Spanish nobility[]

Several lines of descendants exist in Mexico and Spain through Moctezuma II's son and daughters, notably Tlacahuepan Ihualicahuaca, or Pedro Moctezuma, and Tecuichpoch Ixcaxochitzin, or Isabel Moctezuma. Following the conquest, Moctezuma's daughter, Techichpotzin (or Tecuichpoch), became known as Isabel Moctezuma and was given a large estate by Cortés, who also fathered a child by her, Leonor Cortés Moctezuma, who in turn was the mother of Isabel de Tolosa Cortés de Moctezuma.[36][37] Isabel married consecutively to Cuauhtémoc (the last Mexican sovereign), to a conquistador in Cortés' original group, Alonso Grado (died c. 1527), a poblador (a Spaniard who had arrived after the fall of Tenochtitlán), to Pedro Andrade Gallego (died c. 1531), and to conquistador Juan Cano de Saavedra, who survived her.[38] She had children by the latter two, from whom descend the illustrious families of Andrade-Montezuma and Cano-Montezuma. A nephew of Moctezuma II was Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin.

The grandson of Moctezuma II, Pedro's son, Ihuitemotzin, baptized as Diego Luis de Moctezuma, was brought to Spain by King Philip II. There he married Francisca de la Cueva de Valenzuela.[39] In 1627, their son Pedro Tesifón de Moctezuma was given the title Count of Moctezuma (later altered to Moctezuma de Tultengo), and thus became part of the Spanish nobility. In 1766, the holder of the title became a Grandee of Spain. In 1865 (coincidentally during the Second Mexican Empire), the title, which was held by Antonio María Moctezuma-Marcilla de Teruel y Navarro, 14th Count of Moctezuma de Tultengo, was elevated to that of a Duke, thus becoming Duke of Moctezuma, with de Tultengo again added in 1992 by Juan Carlos I.

Descendants of Pedro Tesifón de Moctezuma included (through an illegitimate child of his son Diego Luis) General Jerónimo Girón-Moctezuma, 3rd Marquess de las Amarilas (1741–1819), a ninth-generation descendant of Moctezuma II, who was commander of the Spanish forces at the Battle of Fort Charlotte, and his grandson, Francisco Javier Girón y Ezpeleta, 2nd Duke of Ahumada and 5th Marquess of the Amarillas who was the founder of the Guardia Civil in Spain.[40] Other holders of Spanish noble titles that descend from the Aztec emperor include Dukes of Atrisco.[41]

Indigenous mythology and folklore[]

Many indigenous peoples in Mexico are reported to worship deities named after the Aztec ruler, and often a part of the myth is that someday the deified Moctezuma shall return to vindicate his people. In Mexico, the contemporary Pames, Otomi, Tepehuán, Totonac, and Nahua peoples are reported to worship earth deities named after Moctezuma.[42] His name also appears in Tzotzil Maya ritual in Zinacantán where dancers dressed as a rain god are called "Moctezumas".[43]

Hubert Howe Bancroft, writing in the 19th century (Native Races, Volume #3), speculated that the name of the historical Aztec emperor Moctezuma had been used to refer to a combination of different cultural heroes who were united under the name of a particularly salient representative of Mesoamerican identity.

Symbol of indigenous leadership[]

As a symbol of resistance against the Spanish, the name of Moctezuma has been invoked in several indigenous rebellions.[citation needed] One such example was the rebellion of the Virgin Cult in Chiapas in 1721, where the followers of the Virgin Mary rebelled against the Spanish after having been told by an apparition of the virgin that Moctezuma would be resuscitated to assist them against their Spanish oppressors. In the Quisteil rebellion of the Yucatec Maya in 1761, the rebel leader Jacinto Canek reportedly called himself "Little Montezuma".[44]

Portrayals and cultural references[]

Art, music, and literature[]

The Aztec emperor is the title character in several 18th-century operas: Motezuma (1733) by Antonio Vivaldi;[45] Motezuma (1771) by Josef Mysliveček; Montezuma (1755) by Carl Heinrich Graun; and Montesuma (1781) by Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli. He is also the subject of Roger Sessions' dodecaphonic opera Montezuma (1963), and the protagonist in the modern opera La Conquista (2005) by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero, where his part is written in the Nahuatl language.

Numerous other works of popular culture have mentioned or referred to Moctezuma:

- Moctezuma (spelled Montezuma) is portrayed in Lew Wallace's first novel The Fair God (1873). He is portrayed as influenced by the belief that Cortés was Quetzalcoatl returned, and as a weak and indecisive leader, saving the conquistadores from certain defeat in one battle by ordering the Aztecs to stop.[46]

- The Marines' Hymn's opening line "From the Halls of Montezuma" refers to the Battle of Chapultepec in Mexico City during the Mexican–American War, 1846–1848.

- Montezuma is mentioned in Neil Young's song "Cortez the Killer", from the 1975 album Zuma (the title of which is also believed to derive from "Montezuma"). The song's lyrics paint a heavily romanticized portrait of Montezuma and his empire.

- On the facade of the Royal Palace of Madrid there is a statue of the emperor Moctezuma II, along with another of the Inca emperor Atahualpa, among the statues of the kings of the ancient kingdoms that formed Spain.

- In the alternate history of Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy stories, where the Aztecs were conquered by an Anglo-French Empire rather than by Spain, Moctezuma II was converted to Christianity and retained his rule of Mexico as a vassal of the London-based king, and Moctezuma's descendants were still ruling in this capacity in the equivalent of the 20th century.

- The video game Age of Empires II: The Conquerors contains a six-chapter campaign titled "Montezuma".

Other references[]

- Moctezuma River and Mount Moctezuma, a volcano in Mexico City, are named after him.

- Montezuma Falls in Tasmania is named after him.

- Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma Brewery, a brewery of Heineken International in Monterrey, Mexico, is named after Moctezuma II and his nephew, Cuauhtémoc.

- Montezuma Castle and Montezuma Well, 13th-century Sinagua dwellings in central Arizona, were named by 19th-century American pioneers who mistakenly thought they were built by the Aztecs.

- Montezuma is a playable ruler for the Aztec in several of the video games of the Civilization series.

- Several species of animals and plants such as Montezuma quail, Montezuma oropendola, Argyrotaenia montezumae, and Pinus montezumae have been named after him.

- An elementary school in Albuquerque, New Mexico is named Montezuma Elementary School, after him.

- "Montezuma's Revenge" is a colloquialism for traveler's diarrhea in visitors to Mexico. The urban legend states that Montezuma II initiated the onslaught of diarrhea on "gringo" travelers to Mexico in retribution for the slaughter and subsequent enslavement of the Aztec people by Hernán Cortés in 1521.[47]

See also[]

- Historic recurrence

- List of unsolved murders

- Moctezuma I

- Moctezuma's Table

- Montezuma's headdress

- Qualpopoca

- Emperor

Notes[]

- ^ Classical Nahuatl: Motēuczōmah Xōcoyōtzin [moteːkʷˈsoːma ʃoːkoˈjoːtsin]

- ^ See the account of Moctezuma's captivity, as given in Díaz del Castillo (1963, pp. 245–299).

- ^ Cacique is a hispanicized word of Caribbean origins, meaning "hereditary lord/chief" or "(military) leader". After first encountering the term and office in the Caribbean, conquest-era writers such as Díaz often used it to describe indigenous rulers generally.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec warfare: imperial expansion and political control. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 188. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1. OCLC 17106411.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williamson, Edwin (1992). The Penguin history of Latin America. New York: Penguin Books. p. 18. ISBN 0-14-012559-0. OCLC 29998568.

- ^ Andrews, J. Richard (2003) [1975]. Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Revised Edition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 599.

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G. (1890). Ancient Nahuatl Poetry.

- ^ British Museum Exhibition Guide for Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler (2009)

- ^ http://whp.uoregon.edu/dictionaries/nahuatl/index.lasso

- ^ "Coronation Stone of Motecuhzoma II". Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Moctezuma II Xocoyotl". Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Townsend, Camilla (2019). Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-19-067306-2.

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Translated by J.M. Cohen, New York: Penguin, 1963, p. 220

- ^ Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press (2003), ISBN 0-19-516077-0

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Translated by J.M. Cohen, New York: Penguin, 1963, pp. 216-219

- ^ Townsend, Camilla. Malintzins choices: an Indian woman in the conquest of Mexico. Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2007, Page 86–88.

- ^ Díaz, Bernal (2008). Carrasco, Davíd (ed.). The History of the Conquest of New Spain. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-8263-4287-4. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (October 10, 2013). "Montezuma". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Díaz, Bernal (2008). Carrasco, Davíd (ed.). The History of the Conquest of New Spain. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8263-4287-4. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Nardo, Don (2009). The Spanish Conquistadors. Lucent Books. p. 57.

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Translated by J.M. Cohen, New York: Penguin, 1963, pp. 224–225.

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Translated by J.M. Cohen, New York: Penguin, 1963, p. 294.

- ^ Hernan Cortes: Letters from Mexico. Translated by Anthony Pagden. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Hernan Cortes: Letters from Mexico. Translated by Anthony Pagden. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1986:467.

- ^ Guzman, Eulalia. Relaciones de Hernan Cortes a Carlos V sobre la invasion de Anáhuac. Vol. I. Mexico, 1958, p. 279.

- ^ Restall 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lockhart 1993, pp. 17–19

- ^ Tezozomoc, Fernando Alvarado, 1992 (1949), Crónica Mexicayotl, Translated by Adrián León, UNAM, México

- ^ Restall 2003, chapter 6

- ^ Restall, 2003, p. 97

- ^ Martínez 1980

- ^ Restall, 2003, chapter 6

- ^ Gillespie, 1989, Chapter 5.

- ^ Chipman, D. (2005). The Patrimony of Mariana and Pedro Moctezuma. In Moctezuma's Children: Aztec Royalty under Spanish Rule, 1520–1700 (pp. 75-95). University of Texas Press. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/706286.8

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1883) History of Mexico, Vol. L 1516–1521.

- ^ Sweet, David G. & Gary B. Nash, Luis (1981). Struggle and Survival in Colonial America (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04110-0., page 215

- ^ Chipman, D. (2005). The Patrimony of Mariana and Pedro Moctezuma. In Moctezuma's Children: Aztec Royalty under Spanish Rule, 1520–1700 (pp. 75-95). University of Texas Press. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/706286.8

- ^ González-Obregón, Luis (1992). Las Calles de México (1st ed.). Ciudad de México, DF: Editorial Porrúa. ISBN 968-452-299-1.

- ^ Robert Himmerich y Valencia, The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521-1555. Austin: University of Texas Press 1991, p.196.

- ^ Donald E. Chipman, Moctezuma's Children: Aztec Royalty Under Spanish Rule, 1520-1700. Austin: University of Texas Press 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Robert Himmerich y Valencia, ibid. p.195, 134–35.

- ^ "Project MUSE". Muse.jhu.edu. doi:10.1353/tam.2007.0045. S2CID 144939572. Retrieved 16 November 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "A Descendant of Moctezuma at the Battle of Mobile, 1780". Book-smith.tripod.com. 4 January 2001. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Chipman, Donald E (2005). Moctezuma's children: Aztec royalty under Spanish rule, 1520–1700. ISBN 978-0-292-70628-6.

- ^ Gillespie 1989:165–66

- ^ Bricker,1981:138–9

- ^ Bricker,1981:73

- ^ "La ópera sobre Moctezuma compuesta por Antonio Vivaldi". México Desconocido (in Spanish). 13 October 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Wallace, Lew (1873). The Fair God or the Last of the 'Tzins. New York: Grosset and Dunlap.

- ^ http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/aztec-capital-falls-to-corts

Further reading[]

- Bueno Bravo,Isabel (2006). "Moctezuma Xocoyotzin y Hernán Cortés: dos visiones de una misma realidad" (PDF). Revista Española de Antropología Americana (in Spanish). 36 (2): 17–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-01.

- Chipman, Donald E. (2005). Moctezuma's Children: Aztec Royalty Under Spanish rule, 1520-1700. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72597-3.

- Cohen, Sara E. "How the Aztecs Appraised Montezuma." History Teacher (1972): 21-30. online

- González-Obregón, Luis (1992). Las Calles de México (1st ed.). Ciudad de México, DF: Editorial Porrúa. ISBN 968-452-299-1.

- Graulich, Michel (1994). Montezuma ou l'apogée et la chute de l'empire aztèque (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- Hajovsky, Patrick Thomas. On the Lips of Others: Moteuczoma's Fame in Aztec Monuments and Rituals. Austin: University of Texas Press 2015.

- Lockhart, James (ed. and trans.) (1993);We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Martínez, Jose Luis (1980). "Gerónimo de Mendieta". Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl, UNAM, Mexico. 14: 131–197.

- McEwan Colin and Leonardo López Luján (eds) (2009). Moctezuma Aztec Ruler. London: The British Museum Press.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Phelan, John Leddy (1970) [1956]. The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World: A Study of the Writings of Gerónimo de Mendieta (1525–1604) (2nd edition, revised ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01404-9. OCLC 88926.

- Sanchez, Gonzalo M. (2015). "Did Emperor Moctezuma II's head injury and subsequent death hasten the fall of the Aztec nation?". Neurosurgical Focus. 39 (1): E2. doi:10.3171/2015.4.FOCUS1593. PMID 26126401.

- Thomas, Hugh (2013) [1993]. Conquest, Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico. Touchstone; Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439127254.

- Townsend, Richard F. (2000). The Aztecs (2nd edition, revised ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28132-7. OCLC 43337963.

- Tsouras, Peter. Montezuma: Warlord of the Aztecs (Potomac Books, 2005). excerpt

- Vazquez Chamorro, Germán (1981). "Las reformas socio-económicas de Motecuhzoma II". Revista española de antropología americana (in Spanish). 11: 207–218. ISSN 0556-6533.

- Vazquez Chamorro, Germán (2006). Moctezuma (in Spanish). EDAF. ISBN 978-84-96107-53-3.

- Weaver, Muriel Porter (1993). The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-739065-0. OCLC 25832740.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moctezuma II. |

- A reconstructed portrait of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, based on historical sources, in a contemporary style.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Tenochca tlatoque

- Moctezuma family

- 16th-century rulers

- 16th-century monarchs in North America

- 15th-century indigenous people of the Americas

- 16th-century indigenous people of the Americas

- 16th-century Mexican people

- 1460s births

- 1520 deaths

- 16th-century murdered monarchs

- 1520 crimes

- 1500s in the Aztec civilization

- 1510s in the Aztec civilization

- 1520s in the Aztec civilization

- 15th century in the Aztec civilization

- 16th century in the Aztec civilization

- 1520 in North America

- Dethroned monarchs