Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin 30 May 1814 Pryamukhino, Tver Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Kuvshinovsky District, Tver Oblast, Russia) |

| Died | 1 July 1876 (aged 62) Bern, Switzerland |

| Era | 19th century philosophy |

| Region |

|

| School | |

show

Influences | |

show

Influenced | |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

|

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin[a] (/bəˈkuːnɪn/;[4] 30 May [O.S. 18 May] 1814 – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary socialist and social anarchist tradition.[5] Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

Bakunin grew up in Pryamukhino, a family estate in Tver Governorate. From 1840, he studied in Moscow, then in Berlin hoping to enter academia. Later in Paris, he met Karl Marx and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who deeply influenced him. Bakunin's increasing radicalism ended hopes of a professorial career. He was expelled from France for opposing Russia's occupation of Poland. In 1849, he was arrested in Dresden for his participation in the Czech rebellion of 1848 and deported to Russia, where he was imprisoned first in Saint Petersburg, then in the Shlisselburg fortress from 1854 and finally exiled to Siberia in 1857. He escaped via Japan to the United States and then to London, where he worked with Alexander Herzen on the journal Kolokol (The Bell). In 1863, Bakunin left to join the insurrection in Poland, but he failed to reach it and instead spent time in Switzerland and Italy.

In 1868, Bakunin joined the International Working Men's Association, leading the anarchist faction to rapidly grow in influence. The 1872 Hague Congress was dominated by a struggle between Bakunin and Marx, who was a key figure in the General Council of the International and argued for the use of the state to bring about socialism. On the other hand, Bakunin and the anarchist faction argued for the replacement of the state by federations of self-governing workplaces and communes. Bakunin could not reach the Netherlands and the anarchist faction lost the debate in his absence. Bakunin was expelled from the International for maintaining, in Marx's view, a secret organisation within the International and founded the Anti-Authoritarian International in 1872. From 1870 until his death in 1876, Bakunin wrote his longer works such as Statism and Anarchy and God and the State, but he continued to directly participate in European worker and peasant movements. In 1870, he was involved in an insurrection in Lyon, France. Bakunin sought to take part in an anarchist insurrection in Bologna, Italy, but his declining health forced him to return to Switzerland in disguise.

Bakunin is remembered as a major figure in the history of anarchism, an opponent of Marxism, especially of the dictatorship of the proletariat and for his predictions that Marxist regimes would be one-party dictatorships over the proletariat, not by the proletariat. His book God and the State has been widely translated and remains in print. Bakunin continues to influence anarchists such as Noam Chomsky.[6] Bakunin has had a significant influence on thinkers such as Peter Kropotkin, Errico Malatesta, Herbert Marcuse, E. P. Thompson, Neil Postman and A. S. Neill as well as syndicalist organizations such as the Wobblies, the anarchists in the Spanish Civil War and contemporary anarchists involved in the modern-day anti-globalization movement.[7]

Biography[]

Early years[]

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was born to a Russian noble family in the village situated between Torzhok and Kuvshinovo. His father (1768–1854) was a career diplomat who served in Italy and France, and upon his return settled down at the paternal estate and became a Marshal of Nobility. According to the family legend, the Bakunin dynasty was founded in 1492 by one of the three brothers of the noble Báthory family who left Hungary to serve under Vasili III of Russia.[8] But the first documented ancestor was a 17th-century Moscow dyak (clerk) Nikifor Evdokimov nicknamed Bakunya (from the Russian bakunya, bakulya meaning "chatterbox, phrase monger").[9][10] Alexander's mother, knyazna Lubov Petrovna Myshetskaya, belonged to the impoverished Upper Oka Principalities branch of the Rurik dynasty founded by Mikhail Yurievich Tarussky, grandson of Michael of Chernigov.[11]

In 1810, Alexander married Varvara Alexandrovna Muravyova (1792—1864), who was 24 years younger than him. She came from the ancient noble founded in the 15th century by the Ryazan boyar Ivan Vasilievich Alapovsky nicknamed Muravey (meaning "ant") who was granted land in Veliky Novgorod.[12][13] Her second cousins included Nikita Muravyov and Sergey Muravyov-Apostol, key figures in the Decembrist revolt. Alexander's liberal beliefs led to his involvement in a Decembrist club. After Nicolas I became Emperor, Alexander gave up politics and devoted himself to the estate and his children—five girls and five boys, the oldest of whom was Mikhail.[14]

At age 14, Bakunin left for Saint Petersburg and became a Junker at the Artillery School, today called Mikhailovskaya Military Artillery Academy. In 1833, he received a rank of Praporshchik and was seconded to serve in an artillery brigade in the Minsk and Grodno Governorates.[15] He did not enjoy the army, and having free time, he spent it on self-education. In 1835, he was seconded to Tver and from there returned to his village. Although his father wanted him to continue in either the military or civil service, Bakunin traveled to Moscow to study philosophy.[15]

Interest in philosophy[]

In Moscow, Bakunin soon became friends with a group of former university students. According to E. H. Carr, they studied idealist philosophy grounded in the poet Nikolay Stankevich, "the bold pioneer who opened to Russian thought the vast and fertile continent of German metaphysics". They also studied Immanuel Kant, then Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. By autumn 1835, Bakunin conceived of forming a philosophical circle in his home town of Pryamukhino. By early 1836 he was back in Moscow, where he published translations of Johann Gottlieb Fichte's Some Lectures Concerning the Scholar's Vocation and The Way to a Blessed Life, which became his favorite book. With Stankevich, Bakunin also read Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller and E. T. A. Hoffmann.

Bakunin became increasingly influenced by Hegel and made the first Russian translation of his work. During this period, he met Slavophile Konstantin Aksakov, Pyotr Chaadayev and socialists Alexander Herzen and Nikolay Ogarev. He developed his pan-Slavic views. After long wrangles with his father, Bakunin went to Berlin in 1840. His stated plan was to become a university professor (a "priest of truth" as he and his friends imagined it), but he soon met and joined students of the Young Hegelians and the socialist movement. In his 1842 essay "The Reaction in Germany", he argued for the revolutionary role of negation, summed up in the phrase "the passion for destruction is a creative passion".[16]

After three semesters in Berlin, Bakunin went to Dresden where he became friends with Arnold Ruge. Here, he also read Lorenz von Stein's Der Sozialismus und Kommunismus des heutigen Frankreich and developed a passion for socialism. He abandoned his interest in an academic career, and devoted more and more time to promoting revolution. The Russian government, becoming aware of this activity, ordered him to return to Russia. On his refusal, his property was confiscated. Instead, he went with Georg Herwegh to Zürich, Switzerland.

Early nationalism[]

In his pre-anarchist years, Bakunin's politics were essentially a left-wing form of nationalism, specifically a focus on East Europe and Russian affairs. While at this time he located the national liberation and democratic struggles of the Slavs in a larger European revolutionary process, Bakunin did not pay much attention to other regions. This aspect of his thought dates from before he became an anarchist and his anarchist works consistently envisaged a global social revolution, including Africa and Asia. As an anarchist, Bakunin continued to stress the importance of national liberation, but he now insisted that this issue had to be solved as part of the social revolution. The same problem that in his view dogged Marxist revolutionary strategy (the capture of revolution by small elite which would then oppress the masses) would also arise in independence struggles led by nationalism, unless the working class and peasantry created an anarchy, arguing:

I feel myself always the patriot of all oppressed fatherlands. [...] Nationality [...] is a historic, local fact which, like all real and harmless facts, has the right to claim general acceptance. [...] Every people, like every person, is involuntarily that which it is and therefore has a right to be itself. [...] Nationality is not a principle; it is a legitimate fact, just as individuality is. Every nationality, great or small, has the incontestable right to be itself, to live according to its own nature. This right is simply the corollary of the general principal of freedom.[17]

When Bakunin visited Japan after his escape from Siberia, he was not really involved in its politics or with the Japanese peasants.[18] This might be taken as evidence of a basic disinterest in Asia, but that would be incorrect as Bakunin stopped over briefly in Japan as part of a hurried flight from 12 years of imprisonment, a marked man racing across the world to his European home. Bakunin had neither Japanese contacts nor any facility in the Japanese language and the small number of expatriate newspapers by Europeans published in China and Japan provided no insights into local revolutionary conditions or possibilities.[19] Furthermore, Bakunin's conversion to anarchism came in 1865, towards the end of his life and four years after his time in Japan.[citation needed]

Switzerland, Brussels, Prague, Dresden and Paris[]

During his six-month stay in Zürich , Bakunin associated with German communist Wilhelm Weitling. Until 1848, he was friendly with the German communists, occasionally calling himself communist and writing articles on communism in the Schweitzerische Republikaner. He moved to Geneva soon before Weitling's arrest. His name had appeared often in Weitling's correspondence seized by the police. This led to reports to the imperial police. The Russian ambassador in Bern ordered Bakunin to return to Russia. Instead, he went to Brussels, where he met many leading Polish nationalists, such as Joachim Lelewel, co-member with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Lelewel greatly influenced him, but he clashed with the Polish nationalists over their demand for a historic Poland based on the borders of 1776 (before the Partitions of Poland) as he defended the right of autonomy for the non-Polish peoples in these territories. He also did not support their clericalism and they did not support his calls for the emancipation of the peasantry.

In 1844, Bakunin went to Paris, then a centre of the European political current. He made contact with Karl Marx and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who greatly impressed him and with whom he formed a personal bond. In December 1844, Emperor Nicholas I issued a decree that stripped Bakunin of his privileges as a noble, confiscated his land in Russia, and exiled him for life in Siberia. He responded with a long letter to La Réforme, denouncing the Emperor as a despot and calling for democracy in Russia and Poland (Carr, p. 139).

In another letter to the Constitutionel in March 1846, he defended Poland after the repression of Catholics there. After the defeat of the uprising in Kraków, Polish refugees from there invited him to speak[20] at the November 1847 meeting commemorating the Polish November Uprising of 1830. In his speech, Bakunin called for an alliance of the Polish and Russian peoples against the Emperor, and looked forward to "the definitive collapse of despotism in Russia". As a result, he was expelled from France and went to Brussels.

Bakunin failed to draw Alexander Herzen and Vissarion Belinsky into revolutionary action in Russia. In Brussels, he renewed contacts with revolutionary Poles and Karl Marx. He spoke at a meeting organised by Lelewel in February 1848 about a great future for the Slavs, who would rejuvenate the Western world. Around this time, the Russian embassy circulated rumours that Bakunin was a Russian agent who had exceeded his orders.

The break out of the revolutionary movement of 1848 made Bakunin ecstatic, but he was disappointed that little was happening in Russia. Bakunin received funding from some socialists in the Provisional Government, Ferdinand Flocon, Louis Blanc, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin and Alexandre Martin, for a project for a Slav federation liberating those under the rule of Prussia, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. He left for Germany, travelling through Baden to Frankfurt and Cologne.

Bakunin supported the , led by Herwegh, in an abortive attempt to join Friedrich Hecker's insurrection in Baden. He broke with Marx over the latter's criticism of Herwegh. Much later, in 1871, Bakunin was to write: "I must openly admit that in this controversy Marx and Engels were in the right. With characteristic insolence, they attacked Herwegh personally when he was not there to defend himself. In a face-to-face confrontation with them, I heatedly defended Herwegh, and our mutual dislike began then."[21]

Bakunin went on to Berlin, but was stopped by police from traveling to Posen, part of Polish territories gained by Prussia in the Partitions of Poland, where a nationalist insurrection was taking place. Instead, Bakunin went to Leipzig and Breslau and then on to Prague, where he participated in the First Pan Slav Congress. The Congress was followed by an abortive insurrection that Bakunin had promoted, but which was violently suppressed.

Richard Wagner's autobiography recounts Bakunin's visit:[22]

First of all, however, with the view of adapting himself to the most Philistine culture, he had to submit his huge beard and bushy hair to the tender mercies of the razor and shears. As no barber was available, Rockel had to undertake the task. A small group of friends watched the operation, which had to be executed with a dull razor, causing no little pain, under which none but the victim himself remained passive. We bade farewell to Bakunin with the firm conviction that we should never see him again alive. But in a week he was back once more, as he had realised immediately what a distorted account he had received as to the state of things in Prague, where all he found ready for him was a mere handful of childish students. These admissions made him the butt of Rockel's good-humoured chaff, and after this he won the reputation among us of being a mere revolutionary, who was content with theoretical conspiracy. Very similar to his expectations from the Prague students were his presumptions with regard to the Russian people.

Bakunin published his Appeal to the Slavs[23] in the fall of 1848, in which he proposed that Slav revolutionaries unite with Hungarian, Italian and German revolutionaries to overthrow the three major European autocracies, the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia.

Bakunin played a leading role in the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849, helping to organize the defense of the barricades against Prussian troops with Richard Wagner and Wilhelm Heine. Bakunin was captured in Chemnitz and held for 13 months, then condemned to death by the government of Saxony. His sentence was commuted to life to allow his extradition to Russia and Austria, both of whom sought to prosecute him. In June 1850, he was handed to the Austrian authorities. Eleven months later he received a further death sentence but this too was commuted to life imprisonment. Finally, in May 1851, Bakunin was handed over to the Russian authorities.

Imprisonment, "confession" and exile[]

Bakunin was taken to the Peter and Paul Fortress. At the beginning of his captivity, Alexey Fyodorovich Orlov, an emissary of the Tsar, visited Bakunin and told him that the Tsar requested a written confession.[24][25]

After three years in the dungeons of the fortress, he spent another four years in the castle of Shlisselburg. Due to his diet, he suffered from scurvy and all his teeth fell out. Later, he recounted that he found relief in mentally re-enacting the legend of Prometheus. His continuing imprisonment in these awful conditions led him to entreat his brother to supply him with poison.

Novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago (published in 1973) recounts that Bakunin "abjectly groveled before Nicholas I — thereby avoiding execution. Was this wretchedness of soul? Or revolutionary cunning?"[26][relevant?]

Following the death of Nicholas I, the new Tsar Alexander II personally struck Bakunin's name off the amnesty list. In February 1857, his mother's pleas to the Tsar were finally heeded and he was allowed to go into permanent exile in the western Siberian city of Tomsk. Within a year of arriving in Tomsk, Bakunin married Antonina Kwiatkowska, the daughter of a Polish merchant. He had been teaching her French. In August 1858, Bakunin was visited by his second cousin, General Count Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, who had been governor of Eastern Siberia for ten years.

Muravyov was a liberal and Bakunin, as his relative, became a particular favourite. In the spring of 1859 Muravyov helped Bakunin with a job for Amur Development Agency which allowed him to move with his wife to Irkutsk, the capital of Eastern Siberia. This brought Bakunin to the circle of political discussion at Muravyov's colonial headquarters. Saint Petersburg's treatment of the colony, including the dumping of malcontents there, fostered resentment. This inspired a proposal for a United States of Siberia, independent of Russia and federated into a new United States of Siberia and America, following the example of the United States of America. The circle included Muravyov's young Chief of Staff Kukel, who Peter Kropotkin related had the complete works of Alexander Herzen; the civil governor Izvolsky, who allowed Bakunin to use his address for correspondence; and Muravyov's deputy and eventual successor, General Alexander Dondukov-Korsakov.

When Herzen criticised Muravyov in The Bell, Bakunin wrote vigorously in his patron's defence.[27] Bakunin tired of his job as a commercial traveller, but thanks to Muravyov's influence, was able to keep his sinecure (worth 2,000 roubles a year) without having to perform any duties. Muravyov was forced to retire from his post as governor general, partly because of his liberal views and partly due to fears he might take Siberia towards independence. He was replaced by Korsakov, who perhaps was even more sympathetic to the plight of the Siberian exiles. Korsakov was also related to Bakunin, Bakunin's brother Paul having married his cousin. Taking Bakunin's word, Korsakov gave him a written permission to board all ships on the Amur River and its tributaries as long as he was back in Irkutsk when the ice came.

Escape from exile and return to Europe[]

On 5 June 1861, Bakunin left Irkutsk under cover of company business, ostensibly employed by a Siberian merchant to make a trip to Nikolaevsk. By 17 July, he was aboard the Russian warship Strelok bound for Kastri, in Greece. However, in the port of Olga, he persuaded the American captain of the SS Vickery to take him aboard. Despite encountering the Russian Consul on board, Bakunin sailed away under the nose of the Russian Imperial Navy. By 6 August, he had reached Hakodate in the northernmost Japanese island of Hokkaidō and continued south to Yokohama.

In Japan, Bakunin, by happenstance, met Wilhelm Heine, a comrade-in-arms from Dresden. He also met the German botanist Philipp Franz von Siebold who had been involved in opening up Japan to Europeans (particularly the Russians and the Dutch) and was a friend of Bakunin's patron Muraviev.[28] Von Siebold's son wrote some 40 years later:

In that Yokohama boarding-house we encountered an outlaw from the Wild West Heine, presumably as well as many other interesting guests. The presence of the Russian revolutionist Michael Bakunin, in flight from Siberia, was as far as one could see being winked at by the authorities. He was well-endowed with money, and none who came to know him could fail to pay their respects.

With his ideas still developing, Bakunin left Japan from Kanagawa on the SS Carrington. He was one of 16 passengers, including Heine, Rev. P. F. Koe, and Joseph Heco. Heco was a Japanese American, who eight years later played a significant role giving political advice to Kido Takayoshi and Itō Hirobumi during the revolutionary overthrow of the feudal Tokugawa shogunate.[29] They arrived in San Francisco on 15 October. Bakunin boarded the Orizaba for Panama (the quickest route to New York), and after waiting two weeks boarded the Champion for New York.

In Boston, Bakunin visited , a partisan of Ludwik Mieroslawski during the 1848 Revolution in Paris, and caught up with other "Forty-Eighters", veterans of the 1848 revolutions in Europe, such as Friedrich Kapp.[30] He then sailed for Liverpool, arriving on December 27. Bakunin immediately went to London to see Herzen. That evening he burst into the drawing-room where the family was having supper. "What! Are you sitting down eating oysters! Well! Tell me the news. What is happening, and where?!"[31]

Relocation to Italy and influence in Spain[]

Having re-entered Western Europe, Bakunin immediately immersed himself in the revolutionary movement. In 1860, while still in Irkutsk, Bakunin and his political associates had been greatly impressed by Giuseppe Garibaldi and his expedition to Sicily, during which he declared himself dictator in the name of Victor Emmanuel II. After his return to London, he wrote to Garibaldi on 31 January 1862: "If you could have seen as I did the passionate enthusiasm of the whole town of Irkutsk, the capital of Eastern Siberia, at the news of your triumphal march across the possession of the mad king of Naples, you would have said as I did that there is no longer space or frontiers."[32]

Bakunin asked Garibaldi to participate in a movement encompassing Italians, Hungarians and South Slavs against both Austria and Turkey. Garibaldi was preparing for the Expedition against Rome. By May, Bakunin's correspondence focused on Italian-Slavic unity and the developments in Poland. By June, he had resolved to move to Italy, but waited for his wife to join him. When he left for Italy in August, Mazzini wrote to Maurizio Quadrio, one of his key supporters, that Bakunin was a good and dependable person. However, with the news of the defeat at Aspromonte, Bakunin paused in Paris where he was briefly involved with Ludwik Mierosławski. However, Bakunin rejected Mieroslawski's chauvinism and refusal to grant any concessions to the peasants.

In September, Bakunin returned to England and focussed on Polish affairs. When the Polish insurrection broke out in January 1863, he sailed to Copenhagen to join the Polish insurgents. They planned to sail across the Baltic in the SS Ward Jackson to join the insurrection. This attempt failed, and Bakunin met his wife in Stockholm before returning to London.

Bakunin focussed again on going to Italy and his friend Aurelio Saffi wrote him letters of introduction to revolutionaries in Florence, Turin, and Milan. Mazzini wrote him letters of commendation to in Genoa and in Florence. Bakunin left London in November 1863, travelled via Brussels, Paris and Vevey, (Switzerland), and arrived in Italy on 11 January 1864. It was here that he first developed his anarchist ideas. Bakunin planned a secret organization of revolutionaries to carry out propaganda and prepare for direct action. He recruited Italians, Frenchmen, Scandinavians and Slavs into the International Brotherhood, also called the Alliance of Revolutionary Socialists.

By July 1866, Bakunin was informing Herzen and Ogarev about the fruits of his work over the previous two years. His secret society then had members in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Britain, France, Spain, and Italy, as well as Polish and Russian members. Among his Polish associates was the former insurgent, Walery Mroczkowski, who became a friend and translator into French.[33] In his Catechism of a Revolutionary of 1866, he opposed religion and the state, advocating the "absolute rejection of every authority including that which sacrifices freedom for the convenience of the state."[34]

Giuseppe Fanelli met Bakunin at Ischia in 1866.[35] In October 1868, Bakunin sponsored Fanelli to travel to Barcelona to share his libertarian visions and recruit revolutionists to the International Workingmen's Association.[36] Fanelli's trip and the meeting he organised during his travels was the catalyst for the Spanish exiles, the largest workers' and peasants' movement in modern Spain and the largest Anarchist movement in modern Europe.[37] Fanelli's tour took him first to Barcelona, where he met and stayed with Elisée Reclus.[37] Reclus and Fanelli disagreed about Reclus' friendships with Spanish republicans, and Fanelli soon left Barcelona for Madrid.[37][38] Fanelli stayed in Madrid until the end of January 1869, conducting meetings to introduce Spanish workers, including Anselmo Lorenzo, to the First International.[39] In February 1869 Fanelli left Madrid, journeying home via Barcelona.[35] While in Barcelona again, he met with painter Josep Lluís Pellicer and his cousin, Rafael Farga Pellicer along with others who were to play an important role establishing the International in Barcelona,[35] as well as the Alliance section.

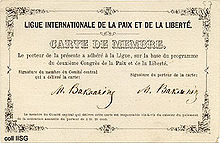

During the 1867–1868 period, Bakunin responded to Émile Acollas's call and became involved in the French League of Peace and Freedom (LPF), for which he wrote a lengthy essay, Federalism, Socialism, and Anti-Theologism.[40] Here, he advocated a federalist socialism, drawing on the work of Proudhon. He supported freedom of association and the right of secession for each unit of the federation, but emphasized that this freedom must be joined with socialism, for "[l]iberty without socialism is privilege, injustice; socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality".

Bakunin played a prominent role in the Geneva Conference of the LPF (September 1867), and joined the Central Committee. The founding conference was attended by 6,000 people. As Bakunin rose to speak, "the cry passed from mouth to mouth: 'Bakunin!' Garibaldi, who was in the chair, stood up, advanced a few steps and embraced him. This solemn meeting of two old and tried warriors of the revolution produced an astonishing impression. [...] Everyone rose and there was a prolonged and enthusiastic clapping of hands".[citation needed] At the Berne Congress of the LPF in 1868, Bakunin and other socialists, Élisée Reclus, , Jaclard, Giuseppe Fanelli, N. Joukovsky, V. Mratchkovsky, and others, found themselves in a minority. They seceded from the LPF, establishing their own International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which adopted a revolutionary socialist program.

First International and rise of the anarchist movement[]

In 1868, Bakunin joined the Geneva section of the First International, in which he remained very active until he was expelled from the International by Karl Marx and his followers at the Hague Congress in 1872. Bakunin was instrumental in establishing the Italian and Spanish branches of the International.

In 1869, the Social Democratic Alliance was refused entry to the First International on the grounds that it was an international organisation in itself, and only national organisations were permitted membership in the International. The Alliance dissolved and the various groups which it comprised joined the International separately.

Between 1869 and 1870, Bakunin became involved with the Russian revolutionary Sergey Nechayev in a number of clandestine projects. However, Bakunin publicly broke with Nechaev over what he described as the latter's "Jesuit" methods, by which all means were justified to achieve revolutionary ends,[citation needed] but privately attempted to maintain contact.[41]

In 1870-1871, Bakunin led a failed uprising in Lyon and Besançon on the principles later exemplified by the Paris Commune, calling for a general uprising in response to the collapse of the French government during the Franco-Prussian War, seeking to transform an imperialist conflict into social revolution. In his Letters to A Frenchman on the Present Crisis, he argued for a revolutionary alliance between the working class and the peasantry, advocated a system of militias with elected officers as part of a system of self-governing communes and workplaces and argued the time was ripe for revolutionary action, stating that "we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda".[42]

These ideas corresponded strikingly closely with the program of the Paris Commune of 1871, much of which was developed by followers of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as the Marxist and Blanquist factions had voted for confrontation with the army while the Proudhonions had supported a truce. Bakunin was a strong supporter of the Commune which was brutally suppressed by the French government. He saw the Commune as above all a "rebellion against the State" and commended the Communards for rejecting not only the state but also revolutionary dictatorship.[43] In a series of powerful pamphlets, he defended the Commune and the First International against the Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini, thereby winning over many Italian republicans to the International and the cause of revolutionary socialism.

Bakunin's disagreements with Marx, which led to the attempt by the Marx party to expel him at the Hague Congress (see below), illustrated the growing divergence between the "anti-authoritarian" sections of the International which advocated the direct revolutionary action and organization of the workers and peasants in order to abolish the state and capitalism and the sections allied with Marx which advocated the conquest of political power by the working class. Bakunin was "Marx’s flamboyant chief opponent" and "presciently warned against the emergence of a communist authoritarianism that would take power over working people."[44]

Bakunin's maxim[]

The anti-authoritarian majority which included most sections of the International created their own International at the 1872 St. Imier Congress, adopted a revolutionary anarchist program, and repudiated the Hague resolutions, rescinding Bakunin's alleged expulsion.[45] Although Bakunin accepted elements of Marx’s class analysis and theories regarding capitalism, acknowledging "Marx’s genius", he thought Marx's analysis was one-sided, and that Marx's methods would compromise the social revolution. More importantly, Bakunin criticized "authoritarian socialism" (which he associated with Marxism) and the concept of dictatorship of the proletariat which he adamantly refused, stating: "If you took the most ardent revolutionary, vested him in absolute power, within a year he would be worse than the Tsar himself".[46]

Personal life[]

In 1874, Bakunin retired with his young wife Antonia Kwiatkowska and three children to Minusio (near Locarno in Switzerland), in a villa called La Baronata that the leader of the Italian anarchists Carlo Cafiero had bought for him by selling his own estates in his native town Barletta (Apulia). His daughter Maria Bakunin (1873–1960) became a chemist and biologist. His daughter Sofia was the mother of Italian mathematician Renato Caccioppoli.

Bakunin died in Bern on 1 July 1876. His grave can be found in Bremgarten Cemetery of Bern, box 9201, grave 68. His original epitaph reads: "Remember he who sacrificed everything for the freedom of his country". In 2015, the commemorative plate was replaced in form of a bronze portrait of Bakunin by Swiss artist Daniel Garbade containing Bakunin's quote: "By striving to do the impossible, man has always achieved what is possible". It was sponsored by the Dadaists of Cabaret Voltaire Zurich, who adopted Bakunin post mortem.

Freemasonry[]

Bakunin joined the Scottish Lodge of the Grand Orient de France in 1845.[47]:128 However his involvement with freemasonry lapsed until he was in Florence in the summer of 1864. Garibaldi had attended first real Italian Masonic Constituent Assembly in Florence in May of that year, and been elected Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy.[48] Here, the local head of the Mazzinist party was also grand master of the local lodge. Although he was soon to dismiss freemasonry, it was in this period that he abandoned his previous belief in a god and embraced atheism. He formulated the phrase "God exists, therefore man is a slave. Man is free, therefore there is no God. Escape this dilemma who can!" which appeared in his unpublished Catechism of a freemason.[49] It was during this period that he established the International Revolutionary Association, he did so with Italian revolutionaries who had broken with Mazzini because they rejected his Deism as well as his purely ‘political’ conception of the revolution, which they saw as being bourgeois with no element of a social revolution.[50]

Thought[]

Bakunin's political beliefs rejected statist and hierarchical systems of power in every name and shape, from the idea of God downwards, and every form of hierarchical authority, whether emanating from the will of a sovereign or even from a state that allowed universal suffrage. He wrote in God and the State that "[t]he liberty of man consists solely in this, that he obeys the laws of nature because he has himself recognized them as such, and not because they have been imposed upon him externally by any foreign will whatsoever, human or divine, collective or individual".[51]

Bakunin similarly rejected the notion of any privileged position or class, since the social and economic inequality implied by class systems were incompatible with individual freedom. Whereas liberalism insisted that free markets and constitutional governments enabled individual freedom, Bakunin insisted that both capitalism and the state in any form were incompatible with the individual freedom of the working class and peasantry, stating that "it is the peculiarity of privilege and of every privileged position to kill the intellect and heart of man. The privileged man, whether he be privileged politically or economically, is a man depraved in intellect and heart". Bakunin's political beliefs were based on several interrelated concepts: (1) liberty; (2) socialism; (3) federalism; (4) anti-theism; and (5) materialism. He also developed a critique of Marxism, predicting that if the Marxists were successful in seizing power, they would create a party dictatorship "all the more dangerous because it appears as a sham expression of the people's will", adding that "[w]hen the people are being beaten with a stick, they are not much happier if it is called 'the People's Stick'".[52]

Authority and freethought[]

Bakunin thought that "[d]oes it follow that I reject all authority? Far from me such a thought. In the matter of boots, I refer to the authority of the bootmaker; concerning houses, canals, or railroads, I consult that of the architect or the engineer. For such or such special knowledge I apply to such or such a savant. But I allow neither the bootmaker nor the architect nor savant to impose his authority upon me. I listen to them freely and with all the respect merited by their intelligence, their character, their knowledge, reserving always my incontestable right of criticism and censure. I do not content myself with consulting a single authority in any special branch; I consult several; I compare their opinions, and choose that which seems to me the soundest. But I recognise no infallible authority, even in special questions; consequently, whatever respect I may have for the honesty and the sincerity of such or such individual, I have no absolute faith in any person".[53]

Bakunin saw that "there is no fixed and constant authority, but a continual exchange of mutual, temporary, and, above all, voluntary authority and subordination. This same reason forbids me, then, to recognise a fixed, constant and universal authority, because there is no universal man, no man capable of grasping in all that wealth of detail, without which the application of science to life is impossible, all the sciences, all the branches of social life".[53]

Anti-theologism[]

| This article is of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

According to political philosopher Carl Schmitt, "in comparison with later anarchists, Proudhon was a moralistic petit bourgeois who continued to subscribe to the authority of the father and the principle of the monogamous family. Bakunin was the first to give the struggle against theology the complete consistency of an absolute naturalism. [...] For him, therefore, there was nothing negative and evil except the theological doctrine of God and sin, which stamps man as a villain in order to provide a pretext for domination and the hunger for power."[54]

Bakunin believed that religion originated from the human ability for abstract thought and fantasy.[43][55] According to Bakunin, religion is sustained by indoctrination and conformism. Other factors in the survival of religion are poverty, suffering and exploitation, from which religion promises salvation in the afterlife. Oppressors take advantage of religion because many religious people reconcile themselves with injustice on earth by the promise of happiness in heaven.[51]

Bakunin argued that oppressors receive authority from religion. Religious people are in many cases obedient to the priests, because they believe that the statements of priests are based on direct divine revelation or scripture. Obedience to divine revelation or scripture is considered the ethical criterion by many religious people because God is considered as the omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. Therefore, each statement considered derived from an infallible God cannot be criticized by humans. According to this religious way of thinking, humans cannot know by themselves what is just, but that only God decides what is good or evil. People who disobey the "messengers of God" are threatened with punishment in hell.[51] According to Bakunin, the alternative for a religious power monopoly is the acknowledgement that all humans are equally inspired by God, but that means that multiple contradictory teachings are assigned to an infallible God which is logically impossible. Therefore, Bakunin considers religion as necessarily authoritarian.[51]

Bakunin argued in his book God and the State that "the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory and practice". Consequently, Bakunin reversed Voltaire's famous aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him, writing instead that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish Him".[51] Political theology is a branch of both political philosophy and theology that investigates the ways in which theological concepts or ways of thinking underlie political, social, economic and cultural discourses. Bakunin was an early proponent of the term political theology in his 1871 text "The Political Theology of Mazzini and the International",[56] to which Schmitt's eponymous book responded.[57][58]

Class struggle strategy for social revolution[]

Bakunin's methods of realizing his revolutionary program were consistent with his principles. The working class and peasantry were to organize from below through local structures federated with each other, "creating not only the ideas, but also the facts of the future itself."[59] Their movements would prefigure the future in their ideas and practices, creating the building blocks of the new society. This approach was exemplified by syndicalism, an anarchist strategy championed by Bakunin, according to which trade unions would provide both the means to defend and improve workers' conditions, rights and incomes in the present, and the basis for a social revolution based upon workplace occupations. The syndicalist unions would organize the occupations as well as provide the radically democratic structures through which workplaces would be self-managed, and the larger economy coordinated. Thus, for Bakunin, the workers' unions would "take possession of all the tools of production as well as buildings and capital."[60]

Nevertheless, Bakunin did not reduce the revolution to syndicalist unions, stressing the need to organize working-class neighborhoods as well as the unemployed. Meanwhile, the peasants were to "take the land and throw out those landlords who live by the labor of others".[42] Bakunin did not dismiss the skilled workers as is sometimes claimed and the watchmakers of the Jura region were central to the St. Imier International's creation and operations. However, at a time when unions largely ignored the unskilled, Bakunin placed great emphasis on the need to organize as well among "the rabble" and "the great masses of the poor and exploited, the so-called "lumpenproletariat" to "inaugurate and bring to triumph the Social Revolution."[61]

Collectivist anarchism[]

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

|

Bakunin's socialism was known as "collectivist anarchism", where "socially: it seeks the confirmation of political equality by economic equality. This is not the removal of natural individual differences, but equality in the social rights of every individual from birth; in particular, equal means of subsistence, support, education, and opportunity for every child, boy or girl, until maturity, and equal resources and facilities in adulthood to create his own well-being by his own labor."[62]

Collectivist anarchism advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production. Instead, it envisions the means of production being owned collectively and controlled and managed by the producers themselves. For the collectivization of the means of production, it was originally envisaged that workers would revolt and forcibly collectivize the means of production.[63] Once collectivization takes place, money would be abolished to be replaced with labour notes and workers' salaries would be determined in democratic organizations based on job difficulty and the amount of time they contributed to production. These salaries would be used to buy goods in a communal market.[64]

Critique of Marxism[]

The dispute between Bakunin and Karl Marx highlighted the differences between anarchism and Marxism. He strongly rejected Marx's concept of the "dictatorship of the proletariat" in which the new state would be unopposed and would, theoretically, represent the workers.[65] He argued that the state should be immediately abolished because all forms of government eventually lead to oppression.[65] He also vehemently opposed vanguardism, in which a political elite of revolutionaries guide the workers. Bakunin insisted that revolutions must be led by the people directly while any "enlightened elite" must only exert influence by remaining "invisible [...] not imposed on anyone [...] [and] deprived of all official rights and significance".[66] Bakunin claimed that Marxists "maintain that only a dictatorship—their dictatorship, of course—can create the will of the people, while our answer to this is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but that of self-perpetuation, and it can beget only slavery in the people tolerating it; freedom can be created only by freedom, that is, by a universal rebellion on the part of the people and free organization of the toiling masses from the bottom up".[67] Bakunin further stated that "we are convinced that liberty without socialism is privilege and injustice; and that socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality".[68]

While both anarchists and Marxists share the same final goal, the creation of a free, egalitarian society without social classes and government, they strongly disagree on how to achieve this goal. Anarchists believe that the classless, stateless society should be established by the direct action of the masses, culminating in social revolution and refuse any intermediate stage such as the dictatorship of the proletariat on the basis that such a dictatorship will become a self-perpetuating fundament. For Bakunin, the fundamental contradiction is that for the Marxists "anarchism or freedom is the aim, while the state and dictatorship is the means, and so, in order to free the masses, they have first to be enslaved."[66] However, Bakunin also wrote of meeting Marx in 1844: "As far as learning was concerned, Marx was, and still is, incomparably more advanced than I. I knew nothing at that time of political economy, I had not yet rid myself of my metaphysical observations. [...] He called me a sentimental idealist and he was right; I called him a vain man, perfidious and crafty, and I also was right".[69] Bakunin found Marx's economic analysis very useful and began the job of translating Das Kapital into Russian. In turn, Marx wrote of the rebels in the Dresden insurrection of 1848 that "they found a capable and cool headed leader" in the "Russian refugee Michael Bakunin."[70] Marx wrote to Friedrich Engels of meeting Bakunin in 1864 after his escape to Siberia, stating: "On the whole he is one of the few people whom I find not to have retrogressed after 16 years, but to have developed further."[71]

Bakunin has sometimes been called the first theorist of the "new class", meaning that a class of intellectuals and bureaucrats running the state in the name of the people or the proletariat, but in reality in their own interests alone. Bakunin argued that "[t]he State has always been the patrimony of some privileged class: a priestly class, an aristocratic class, a bourgeois class. And finally, when all the other classes have exhausted themselves, the State then becomes the patrimony of the bureaucratic class and then falls—or, if you will, rises—to the position of a machine."[61]

Federalism[]

By federalism, Bakunin meant the organization of society "from the base to the summit—from the circumference to the center—according to the principles of free association and federation."[62] Consequently, society would be organized "on the basis of the absolute freedom of individuals, of the productive associations, and of the communes", with "every individual, every association, every commune, every region, every nation" having "the absolute right to self-determination, to associate or not to associate, to ally themselves with whomever they wish."[62]

Liberty[]

By liberty, Bakunin did not mean an abstract ideal but a concrete reality based on the equal liberty of others. In a positive sense, liberty consists of "the fullest development of all the faculties and powers of every human being, by education, by scientific training, and by material prosperity." Such a conception of liberty is "eminently social, because it can only be realized in society", not in isolation. In a negative sense, liberty is "the revolt of the individual against all divine, collective, and individual authority."[72]

Materialism[]

Bakunin denied religious concepts of a supernatural sphere and advocated a materialist explanation of natural phenomena, for "the manifestations of organic life, chemical properties and reactions, electricity, light, warmth and the natural attraction of physical bodies, constitute in our view so many different but no less closely interdependent variants of that totality of real beings which we call matter." For Bakunin, The "mission of science is, by observation of the general relations of passing and real facts, to establish the general laws inherent in the development of the phenomena of the physical and social world."[72]

Proletariat, lumpenproletariat and the peasantry[]

Bakunin differed from Marx's on the revolutionary potential of the lumpenproletariat and the proletariat, for "[b]oth agreed that the proletariat would play a key role, but for Marx the proletariat was the exclusive, leading revolutionary agent while Bakunin entertained the possibility that the peasants and even the lumpenproletariat (the unemployed, common criminals, etc.) could rise to the occasion."[73] According to Nicholas Thoburn, "Bakunin considers workers' integration in capital as destructive of more primary revolutionary forces. For Bakunin, the revolutionary archetype is found in a peasant milieu (which is presented as having longstanding insurrectionary traditions, as well as a communist archetype in its current social form — the peasant commune) and amongst educated unemployed youth, assorted marginals from all classes, brigands, robbers, the impoverished masses, and those on the margins of society who have escaped, been excluded from, or not yet subsumed in the discipline of emerging industrial work – in short, all those whom Marx sought to include in the category of the lumpenproletariat."[74]

Influence[]

Bakunin has had a major influence on labour, peasant and left-wing movements, although this was overshadowed from the 1920s by the rise of Marxist regimes. With the collapse of those regimes—and growing awareness of how closely those regimes corresponded to the dictatorships Bakunin predicted—Bakunin's ideas have rapidly gained ground amongst activists, in some cases again overshadowing neo-Marxism. Bakunin is remembered as a major figure in the history of anarchism and as an opponent of Marxism, especially of Marx's idea of dictatorship of the proletariat and for his astute predictions that Marxist regimes would be one-party dictatorships over the proletariat, not of the proletariat itself. God and the State was translated multiple times by other anarchists such as Benjamin Tucker, Marie Le Compte and Emma Goldman. Bakunin continues to influence modern-day anarchists such as Noam Chomsky.[6]

Mark Leier, Bakunin's biographer, writes that "Bakunin had a significant influence on later thinkers, ranging from Peter Kropotkin and Errico Malatesta to the Wobblies and Spanish anarchists in the Civil War to Herbert Marcuse, E.P. Thompson, Neil Postman, and A.S. Neill, down to the anarchists gathered these days under the banner of 'anti-globalization.'"[7]

Criticism[]

Violence, revolution and invisible dictatorship[]

According to McLaughlin, Bakunin has been accused of being a closet authoritarian. In his letter to Albert Richard, he wrote that "[t]here is only one power and one dictatorship whose organisation is salutary and feasible: it is that collective, invisible dictatorship of those who are allied in the name of our principle".[75] According to Madison, Bakunin "rejected political action as a means of abolishing the state and developed the doctrine of revolutionary conspiracy under autocratic leadership– disregarding the conflict of this principle with his philosophy of anarchism".[76]:48 According to Peter Marshall, "[i]t is difficult not to conclude that Bakunin's invisible dictatorship would be even more tyrannical than a Blanquist or Marxist one, for its policies could not be openly known or discussed."[77]

Madison contended that it was Bakunin's scheming for control of the First International that brought about his rivalry with Karl Marx and his expulsion from it in 1872: "His approval of violence as a weapon against the agents of oppression led to nihilism in Russia and to individual acts of terrorism elsewhere– with the result that anarchism became generally synonymous with assassination and chaos."[76]:48 However, Bakunin's supporters argue that this "invisible dictatorship" is not a dictatorship in any conventional sense of the word. Their influence would be ideological and freely accepted, stating: "Denouncing all power, with what sort of power, or rather by what sort of force, shall we direct a people's revolution? By a force that is invisible [...] that is not imposed on anyone [...] [and] deprived of all official rights and significance."[78]

Bakunin was also criticized by Marx[79] and the delegates of the International specifically because his methods of organization were similar to those of Sergey Nechayev, with whom Bakunin was closely associated.[80] While Bakunin rebuked Nechayev upon discovery of his duplicity as well as his amoral politics, he did retain a streak of ruthlessness, as indicated by a 2 June 1870 letter: "Lies, cunning [and] entanglement [are] a necessary and marvelous means for demoralising and destroying the enemy, though certainly not a useful means of obtaining and attracting new friends."[81]

Nevertheless, Bakunin began warning friends about Nechayev's behavior and broke off all relations with Nechayev. Moreover, others note that Bakunin never sought to take personal control of the International, that his secret organisations were not subject to his autocratic power, and that he condemned terrorism as counter-revolutionary.[82] Robert M. Cutler goes further, pointing out that it is impossible fully to understand either Bakunin's participation in the League of Peace and Freedom or the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, or his idea of a secret revolutionary organisation that is immanent in the people, without seeing that they derive from his interpretation of Hegel's dialectic from the 1840s. Cutler argues that the script of Bakunin's dialectic gave the Alliance the purpose of providing the International with a real revolutionary organisation. Cutler further states:

Marx's advocacy of participation in bourgeois politics, including parliamentary suffrage, would have been proof of [his being a "compromising Negative" in the language of the 1842 "Reaction in Germany" article]. It would have been Bakunin's duty, following the script defined by his dialectic, to bring the [International Working-Men's Association] to a recognition of its true role. [Bakunin's] desire to merge first the League and then the Alliance with the International derived from a conviction that the revolutionaries in the International should never cease to be penetrated to every extremity by the spirit of Revolution. Just as, in Bakunin's dialectic, the consistent Negatives needed the compromisers in order to vanquish them and thereby realize the Negative's true essence, so Bakunin, in the 1860s, needed the International in order to transform its activity into uncompromising Revolution.[83]

Antisemitism[]

Sociologist Marcel Stoetzler claims that Bakunin "put the existence of a Jewish conspiracy to control the world at the center of his political thinking." He points out that, in Bakunin's Appeal to Slavs (1848), "he wrote that the 'Jewish sect' was a 'veritable power in Europe,' reigning despotically over commerce and banking and invading most areas of journalism. 'Woe to him who makes the mistake of displeasing it!'" Stoetzler explains that "Conspiracy thinking, cult of violence, hatred of law, fecundity of destruction, Slavic ethnonationalism and antisemitism ... were inseparable from Bakunin’s revolutionary anarchism."[84][85]

Alvin Rosenfeld, the Director of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism, agrees that Bakunin's antisemitism is intertwined with his anarchist ideology. In his attacks on Marx, for instance, Bakunin states:

- “the communism of Marx wants a mighty centralization by the state, and where this exists there must nowadays be a central State Bank and where such a bank exists, the parasitical Jewish nation, which speculates on the labor of the peoples, will always find a means to sustain itself.”[86][87]

In Bakunin's view, wherever “such a bank exists the parasitic Jewish nation, which speculates in the labor of the people will always find means to exist.”[88] Rosenfeld points out how Bakunin's antisemitic views were tied to his anarchist disdain for a strong centralized bank. Steve Cohen, as well, argues that "Bakuninʹs own justification of anarchy was remarkable in that it was founded explicitly on his own belief in the world Jewish conspiracy. He saw both capitalism and communism as being based on centralised state structures at all times controlled by Jews."[89]

For Bakunin, the Jewish people is not a social demographic, but rather is an exploitative class in and of itself. In letters to the Bologna section of the International, Bakunin writes:

- "This whole Jewish world, comprising a single exploiting sect, a kind of bloodsucking people, a kind of organic destructive collective parasite, going beyond not only the frontiers of states, but of political opinion, this world is now, at least for the most part, at the disposal of Marx on the one hand, and of Rothschild on the other."[90][91][92]

Rosenfeld explains that Bakunin's antisemitism has fed into anti-Jewish populism in 19th century Russia and has left an antisemitic legacy in the anarchist ideological tradition.[88] Rosenfeld brings up the example of a Jewish narodnik who complained about his comrades: “They make no distinction between Jews and gentry; they were "preaching the extermination of both."[88] Rosenfeld explains that radicals often also failed to condemn anti-Jewish populist riots that arose in the 1880s due to their perceived "revolutionary" and "mass" character.[88] Some even went so far as to use popular anti-Jewish sentiment in their ideological advocacy. 'While the reactionaries would use Jewish blood to put out the fire of rebellion," it was noted, "their adversaries were not averse to using it to feed the flames."'[88] Indeed, the Narodnaia Volya of Russia, a pre-Bolshevick organization with Bakuninist and popularist tendencies, called for the masses to revolt against the "Jewish Tzar," for "soon over the whole Russian land there will arise a revolt against the Tsar, the lords and the Jews."[93][94][89]

Bakunin's biographer Mark Leir claimed in an interview with Iain McKay that "Bakunin’s anti-Semitism has been greatly misunderstood. At virtually every talk I’ve given on Bakunin, I’m asked about it. Where it exists, it is repellent, but it takes up about 5 pages of the thousands of pages he wrote, was written in the heat of his battles with Marx, where Bakunin was slandered viciously, and needs to be understood in the context of the 19th century."[95]

Rosenfeld responded that Bakunin's ideas have been since valued independently of his antisemitism, and many of the movements that followed him and many of his greatest admirers, such as Peter Kropotkin, Gustav Landauer, and Rudolf Rocker, harbored no antisemitic belief; Leir's "attitude to situating Proudhon and Bakunin’s politics, however, easily underestimates the force of anti-Jewish prejudice, and how it unconsciously shapes less extrovert aspects of Bakunin's ideology."[96]

Translations[]

English translations of Bakunin's texts are rare compared to the comprehensive editions in French by Arthur Lehning or those in German and Spanish. AK Press is producing an eight-volume complete works in English. Madelaine Grawitz’s biography (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 2000) remains to be translated.

Works[]

Books[]

- God and the State, ISBN 0-486-22483-X

Pamphlets[]

- Stateless Socialism: Anarchism (1953)

- Marxism, Freedom, and the State (1950)

- The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State (1871)

- The Immorality of the State (1953)

- Statism and Anarchy (1990), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521361826

- Revolutionary Catechism (1866)

- The Commune, the Church, and the State (1947)

- Founding of the First International (1953)

- On Rousseau (1972)

- No Gods No Masters (1998) by Daniel Guérin, Edinburgh: AK Press, ISBN 1873176643

Articles[]

- "Power Corrupts the Best" (1867)

- "The Class War" (1870)

- "What is Authority?" (1870)

- "Recollections on Marx and Engels" (1869)

- "The Red Association" (1870)

- "Solidarity in Liberty" (1867)

- "The German Crisis" (1870)

- "God or Labor" (1947)

- "Where I Stand" (1947)

- "Appeal to my Russian Brothers" (1896)

- "The Social Upheaval" (1947)

- "Integral Education, Part I" (1869)

- "Integral Education, Part II" (1869)

- "The Organization of the International" (1869)

- "Polish Declaration" (1896)

- "Politics and the State" (1871)

- "Workers and the Sphinx" (1867)

- "The Policy of the Council" (1869)

- "The Two Camps" (1869)

Collections[]

- Bakunin on Anarchism (1971). Edited, translated and with an introduction by Sam Dolgoff.[97] Preface by Paul Avrich. New York: Knopf Originally published as Bakunin on Anarchy, it includes James Guillaume's Bakunin: A Biographical Sketch. ISBN 0043210120.[98]

- Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings (1974). A. Lehning (ed.). New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0802100201.

- Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume 1: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE-1939) (2005). Robert Graham (ed.). Montreal and New York: Black Rose Books. ISBN 1551642514.

- The Political Philosophy of Bakunin (1953). G. P. Maximoff (ed.). It includes Mikhail Bakunin: A Biographical Sketch by Max Nettlau.

- The Basic Bakunin: Writings 1869–1871 (1992). Robert M. Cutler (ed.). New York: Prometheus Books, 1992. ISBN 0879757450.

- Mikhail Bakunin: The Philosophical Basis of his Anarchism (2002). Paul McLaughlin. New York: Algora Publishing. Paperback edition. ISBN 1-892941-84-8.

- Michała Bakunina filozofia negacji (2007). Jacek Uglik (in Polish). Warsaw: Aletheia. ISBN 9788361182085.

- Bakunin's ideas are examined in depth in Lucien van der Walt and Michael Schmidt's global study of anarchism and syndicalism, Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism (Counter-Power vol. 1), with Bakunin described (along with his compatriot Peter Kropotkin) as one of the two most important figures in anarchist history.

See also[]

- Anarchism in Russia

- List of Russian anarchists

Notes[]

- ^ Russian: Михаил Александрович Бакунин, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ɐlʲɪkʲsɐnʲtrəˈfit͡ɕ bɐˈkunʲɪn]

References[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

- ^ Scanlan, James P. (1998). "Russian Materialism: 'the 1860s'". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-E050-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

- ^ Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James; Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1994). Russian Philosophy Volume II: the Nihilists, The Populists, Critics of Religion and Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 3.

Bakunin himself was a Westernizer

- ^ "Bakunin". Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. 2010.

- ^ Masters, Anthony (1974), Bakunin, the Father of Anarchism, Saturday Review Press, ISBN 0-8415-0295-1

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chomsky, Noam (1970). For Reasons of State. New York: Pantheon Books. (See especially title page and "Notes on Anarchism".)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sale, Kirkpatrick (2006-11-06) An Enemy of the State Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The American Conservative

- ^ Bakunin coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 5, October 22, 1800 (in Russian)

- ^ Bakulyt' article from the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language (in Russian)

- ^ The Bakunins noble family article from the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary at Wikisource (in Russian)

- ^ The Myshetskys article from the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary at Wikisource (in Russian)

- ^ Muravyov coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 1, January 1, 1798 (in Russian

- ^ The Muravyovs, the Russian noble and graf family article from the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary at Wikisource (in Russian)

- ^ Leier, Mark (2006). . Seven Stories Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-58322-894-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Natalia Pirumova (2017). Mikhail Bakunin. Life and Work. — Moscow: Lenand, p. 5-8 ISBN 978-5-9710-4532-8

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail (1842). "The Reaction in Germany". In: Sam Dolgoff (1971, 1980), Bakunin on Anarchy.

- ^ Bonanno, Alfredo M. Anarchism and the National Liberation Struggle. pp. 19–20.

- ^ Library, libcom.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Bakunin's Stop-Over in Japan, Librero International, no, 5, 1978: CIRA-Japan, retrieved February 15, 2013

- ^ On the 17th Anniversary of the Polish Insurrection of 1830, Mikhail Bakunin, La Réforme, December 14, 1847

- ^ Michael Bakunin A Biographical Sketch by James Guillaume

- ^ Richard Wagner, My Life — Volume 1, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Appeal to the Slavs, Mikhail Bakunin, 1848, Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971.

- ^ Voegelin, Eric (2002). The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Volume 6: Anamnesis: On the Theory and History of Politics. Translated by Hanak, M. J. University of Missouri Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780826213501.

- ^ Confession to Tsar Nicholas I, Mikhail Bakunin, 1851

- ^ Translation by Thomas P. Whitney, p.132.

- ^ Bakunin, Yokohama and the Dawning of the Pacific Archived June 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine by Peter Billingsley

- ^ Edgar Franz, Philipp Franz von Siebold and Russian Policy and Action on Opening Japan to the West in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century, Munich: Iudicum 2005

- ^ Joseph Heco (Narrative Writer) James Murdoch (Editor), The Narrative of a Japanese: What He Has Seen and the People He Has Met in the Course of the Last 40 Years, Yokohama, Yokohama Publishing Company (Tokyo, Maruzen), 1895, Vol II, pp 90–98

- ^ Robert M. Cutler,"An Unpublished Letter of M.A. Bakunin to R. Solger", International Review of Social History 33, no. 2 (1988): 212–217

- ^ "Bakunin, Yokohama, and the dawning of the Pacific era". libcom.org. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ Pier Carlo Massini and Gianni Bosio, "Bakunin, Garibaldi e gli affari slavi 1862–1863." Movimento Operaio year 4, No. 1 (Jan–Feb, 1952), p 81

- ^ Lettre de Bakounine, Bakunin's correspondence with Mroczkowski, archive.org

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin, "Revolutionary Catechism", 1866. In Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bookchin 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Bookchin 1998, pp. 12–15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bookchin 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (2010). New Perspectives on Anarchism. ISBN 9780739132418.

- ^ Bookchin 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin, "Federalism, Socialism, Anti-Theologism". September 1867.

- ^ Wheen, Francis Karl Marx pp. 346–7

- ^ Jump up to: a b Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis, Mikhail Bakunin, 1870

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State, Mikhail Bakunin, 1871

- ^ Verslius, Arthur (2005-06-20) Death of the Left?, The American Conservative

- ^ Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE to 1939), Robert Graham, Black Rose Books, March 2005

- ^ Quoted in Daniel Guérin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Car, E. H. (1975). Michael Bakunin (PDF). MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- ^ Politics and the Occult: The Left, the Right, and the Radically Unseen, Gary Lachman page 118

- ^ Mikhail, Bakunin E. H. Carr

- ^ "Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1866". www.marxists.org. Marxist Internet archive. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e God and the State, Michael Bakunin, 1882

- ^ Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, ed. A. Lehning (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. 268.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What is Authority?" by Mikhail Bakunin

- ^ Carl Schmitt (2005). Political Theology. University of Chicago Press. pg. 64

- ^ Michail Bakunin: Political Theology of Mazzinni; (1871); from the book: Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings published in 1973.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (1992). Demanding the Impossible. Harper Collins. pp. 300–1. ISBN 0002178559.

- ^ Maier, Henrich (1995). Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss: The hidden dialogue. University of Chicago Press. pp. 75–6. ISBN 0226518884.

- ^ Schmitt, Carl (1922). Political theology. University of Chicago Press. pp. 64–66. ISBN 0226738892.

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin, Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1871, Marxists.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin, Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1870, Marxists.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b On the International Workingmen's Association and Karl Marx, Mikhail Bakunin, 1872

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Revolutionary Catechism, Mikhail Bakunin, 1866

- ^ Patsouras, Louis. 2005. Marx in Context. iUniverse. p. 54

- ^ Bakunin Mikail. Bakunin on Anarchism. Black Rose Books. 1980. p. 369

- ^ Jump up to: a b Woodcock, George (1962, 1975). Anarchism, 158. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-020622-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mikhail Bakunin, Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1873, Marxists.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Anarchist Theory FAQ Version 5.2, Gmu.edu, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin (1867). "Federalism, Socialism, Anti-Theologism". Marxists.org.

- ^ Quoted in Brian Morris, Bakunin: The Philosophy of Freedom, 1993, p14

- ^ New York Daily Tribune (October 2, 1852) on 'Revolution and Counter Revolution in Germany'

- ^ Quoted in Brian Morris, Bakunin: The Philosophy of Freedom, 1993, p. 29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bakunin, Mikhail. Selected Writings. p. 219.

- ^ "Marxism and Anarchism: The Philosophical Roots of the Marx-Bakunin Conflict – Part Two" by Ann Robertson.

- ^ Nicholas Thoburn. "The lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnameable" in Deleuze, Marx and Politics

- ^ McLaughlin, P Anarchism and authority: a philosophical introduction to classical anarchism, page 19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madison, Charles A. (1945), "Anarchism in the United States", Journal of the History of Ideas, University of Pennsylvania Press, 6 (1): 46–66, doi:10.2307/2707055, JSTOR 2707055

- ^ Marshall, Peter H. (1993). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Fontana. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.

- ^ Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, pp. 191-2

- ^ [1] Marxism versus Anarchism (2001), p. 88.

- ^ David Adam. "Marx, Bakunin, and the Question of Authoritarianism". libcom.org. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Michael Bakunin, “M. Bakunin to Sergey Nechayev,” in Michael Confino, Daughter of a Revolutionary: Natalie Herzen and the Bakunin-Nechayev Circle (London: Alcove Press, 1974), 268. Emphasis added.

- ^ Bakunin, "Program of the International Brotherhood"(1868), reprinted in Bakunin on Anarchism, ed. S. Dolgoff

- ^ Cutler, Robert M., "Introduction" to (Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1992), p. 27, http://www.robertcutler.org/bakunin/basic/intro.html, retrieved 2010-12-29. Cutler also cites Bakunin's "Letter to Pablo," reproduced in Max Nettlau, Michael Bakunin: Eine Biographie (London: By the Author, 1896–1900), p. 284, where Bakunin maintains that the "powerful but always invisible revolutionary collectivity" leaves the "full development [of the revolution] to the revolutionary movement of the masses and the most absolute liberty to their social organization,... but always seeing to it that this movement and this organization should never be able to reconstitute any authorities, governments, or States and always combatting all ambitions collective (such as Marx's) [sic in the original] as well as individual, by the natural, never official, influence of every member of our [International] Alliance [of Socialist-Democracy]."

- ^ Stoetler, Marcel (2014). Antisemitism and the constitution of sociology. University of Nebraska Press. p. 139.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail. Oeuvres Vol 5. pp. 234–244.

- ^ Wistrich, Robert S. (2012). From Ambivalence to Betrayal_ The Left, the Jews, and Israel. University of Nebraska Press. p. 46.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail. Rapports personnels avec Marx, Oeuvres Vol 3. pp. 209–99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (2015). Deciphering the New Antisemitism. Indiana University Press. p. 210.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cohen, Steve (1984). Thatʹs Funny You Donʹt Look Anti‐Semitic. p. 94.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (2015). Deciphering the New Antisemitism. Indiana University Press. pp. 209–210.

- ^ Stoetler, Marcel (2014). Antisemitism and the constitution of sociology. University of Nebraska Press. p. 140.

- ^ Lehning, A; Rüter, A.C.J; Scheibert, P (1963). Bakunin-Archiv vol 1 part 2. Leiden. pp. 124–26.

- ^ Wistrich, Robert S. (2012). From Ambivalence to Betrayal_ The Left, the Jews, and Israel. University of Nebraska Press. p. 187.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (2015). Deciphering the New Antisemitism. Indiana University Press. p. 234.

- ^ Iain, McKay (2009). "Black Flag" (PDF). Bakunin for the 21th century (229). p. 29.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (2015). Deciphering the New Antisemitism. Indiana University Press. p. 235.

- ^ Mikhail Bakunin Reference Archive, Marxists.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

- ^ Karl Marx, Michael Bakunin by James Guillaume, Marxists.org, retrieved September 8, 2009

Bibliography[]

- Bookchin, Murray (1998), The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868–1936, Canada: AK Press, ISBN 1-873176-04-X

- Judaica (1950), Historia judaica, Volumes 12–14, Verlag von Julius Kittls Nachfolger

- Wheen, Francis (1999), Karl Marx, Fourth Estate, ISBN 1-85702-637-3

Further reading[]

- Carr, E. H. Michael Bakunin. London: Macmillan And Co., 1937

- Leier, Mark. Bakunin: The Creative Passion: A Biography. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-312-30538-9).

- Angaut, Jean-Christophe."Revolution and the Slav question : 1848 and Mikhail Bakunin" in Douglas Moggach and Gareth Stedman Jones (eds.) The 1848 revolutions and European political thought. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Guérin, Daniel. Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970 (paperback, ISBN 0-85345-175-3).

- MacLaughlin, Paul. Mikhail Bakunin: the philosophical basis of his anarchism. New York: Algora Publishing, 2002 (ISBN 1-892941-85-6).

- Stoppard, Tom. The Coast of Utopia. New York: Grove Press, 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-8021-4005-X).

- David, Zdeněk V. "Frič, Herzen, and Bakunin: the Clash of Two Political Cultures." East European Politics and Societies 12.1 (1997): 1–30.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikhail Bakunin. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mikhail Bakunin |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Mikhail Bakunin |

- Bakunin Archive at RevoltLib

- Bakunin archive at Anarchy Archives

- Archive of Michail Aleksandrovič Bakunin Papers at the International Institute of Social History

- Writings of Bakunin at Marxist Internet Archive

- Works by Mikhail Aleksandrovic Bakunin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mikhail Bakunin at Internet Archive

- Works by Mikhail Bakunin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Mikhail Bakunin

- 1814 births

- 1876 deaths

- 19th-century atheists

- 19th-century Russian philosophers

- 19th-century Russian writers

- Anarchist theorists

- Anarchist writers

- Antisemitism in the Russian Empire

- Aphorists

- Atheist philosophers

- Collectivist anarchism

- Collectivist anarchists

- Critics of Freemasonry

- Critics of Judaism

- Critics of Marxism

- Critics of religions

- Critics of work and the work ethic

- Cultural critics

- Escapees from Russian detention

- Former Russian Orthodox Christians

- Atheists of the Russian Empire

- Libertarian socialists

- People from Kuvshinovsky District

- People from Lugano

- People from Novotorzhsky Uyezd

- People of the Revolutions of 1848

- Materialists

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- Philosophers of culture

- Philosophers of economics

- Philosophers of history

- Philosophers of nihilism

- Philosophers of religion

- Philosophy writers

- Revolution theorists

- Russian anarchists

- Russian anti-capitalists

- Russian atheism activists

- Russian atheist writers

- Russian escapees

- Russian nihilists

- Russian nobility

- Russian non-fiction writers

- Russian political philosophers

- Russian political writers

- Russian revolutionaries

- Russian socialists

- Russian writers

- Social critics

- Social philosophers

- Theorists on Western civilization

- Russian duellists