Military of the Nguyễn dynasty

The military of the Nguyễn dynasty (Vietnamese: Quân thứ; Chữ Nôm: 軍次) were the military forces of the Nguyễn dynasty from 1802 to August 1945 when it was dismantled. The military was formed in 1790 by loyalists to the Nguyễn lords under the exiled Nguyễn Phúc Ánh. Following the Nguyễn's victory over the Tây Sơn dynasty, it became the national military of Vietnam.

After June 1885 the independent military of the Nguyễn was converted into colonial units under French command with only a small number of leftover forces remaining for provincial defense and the imperial guard.

History[]

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh[]

The Nguyen army was formed in 1790 by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, the former Nguyễn prince in Saigon, with the help and training of several French advisors, though the treaty between Nguyễn Phúc Ánh and Louis XVI in 1787 was never ratified. The Nguyễn loyalists overcame the Taysons in Binh Thuan (1794), Qui Nhon (1799 and 1801), Hue (June 1802), Hanoi (July 1802) to become the first force that able to unify the Vietnamese nation that stretched from Guangxi, China to the Gulf of Thailand, after three centuries of .

Independent period[]

The Imperial army numbered 13,000 men invaded Cambodia in 1809 and 1813 in order to protect the faction of the king Ang Chan II of Cambodia, established the Viceroy of Cambodia, with Trương Tấn Bửu held the title Viceroy. In 1827 they were mobilized for the intervention in the Vientiane Kingdom in Laos. In 1833 when the Chakri Siamese army invaded Cambodia, much of the Nguyen army stationing in Cambodia had to withdraw back to suppress the Lê Văn Khôi revolt and Nông Văn Vân's Rebellion. In 1834 emperor Minh Mang launched the annexation of Cambodia after the Siamese army had been forced to retreat. Minh Mang died in early 1841. Siam launched the second invasion of Cambodia. Although the Nguyen army successfully retook Phnom Penh in 1845, the emperor of Vietnam Thieu Tri sought to make peace with Siam. A peace treaty between Siam and Vietnam was signed in March 1847, which resulted in the independence of Cambodia in 1848. Between 1802 to 1862, the Nguyen army also had faced 405 internal rebellions and revolts from small to large scales, mostly were the Lê Loyalists, ethnic minorities, and princely.[4] The Imperial army gradually lost to France and Spain during the Cochinchina Campaign (1858–1862). After the Treaty of Saigon (1874), Vietnamese military units in Tonkin were eliminated and replaced by police forces.

Under French rule[]

By the time when the French Republic consolidating its rule over Indochina in July 1885, the Imperial army was dismantled, left only 8,000-men royal guards and the colonial army, commanded by French officers.

Organisation[]

The Vietnamese army in 1802 had around 150,000 men served as provincial soldiers (linh co) plus 12,000 royal guards (linh ve), total numbered 162,000 men. During the reign of Minh Mạng (r. 1820–1841), the provincial army was decreased down to 50,000 to 60,000 men. During the reign of Tự Đức (r. 1848–1883), the army reduced itself further to a 44,000 man army (32,000 linh co and 12,000 linh ve), with only ten percent of the linh co soldiers were fully armed and well-disciplined at that time.

Centre army (linh ve)[]

The emperor had about 12,000 centre army soldiers (lính vệ, permanent soldiers, royal guards), obligated to protect the royal capital of Hue and its adjacent areas. They were armed with European muskets, rifles, and bayonets. Linh ve soldiers wore black gauze tunics with flower decorations, red insignia in front and back with characters on them; small hats made of lacquered redwood; sometimes white boots, but most soldiers wore slippers or barefoot.[5]

Provincial army (linh co)[]

| Army structure in 1830[6] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Title | Unit |

| Nhất phẩm | Ngũ quân Đô Thống chưởng phủ sự, Ngũ quân Đô Thống (Marshals, maréchal) | đạo (army, 10,000 soldiers) |

| Nhị phẩm | Thống chế, Đề đốc, Chưởng vệ (generals) | doanh (2,500–4,800 soldiers) |

| Tam phẩm | Lãnh binh, Vệ úy, phó Vệ úy, Đốc binh (imperial colonels) | vệ (500 soldiers) bataillon |

| Tứ phẩm | Quản cơ, phó Quản cơ, Hiệp quản (provincial colonels) | cơ (500 soldiers) régiment |

| Ngũ phẩm | Cai đội (captains) | đội (50 soldiers) compagnie |

| Lục phẩm | Chánh đội trưởng suất đội (lieutenants) | |

| Thất phẩm | Chánh đội trưởng suất thập (sergǣnts) | thập (10 soldiers) escouade |

| Bát phẩm | Đội trưởng suất thập (corporals) | ngũ (5 soldiers) section |

| Cửu phẩm | Thơ lại | individual clerk |

The provincial army had five armies called trung quân (centre army), tả quân (left army), hữu quân (right army), tiền quân (first army), and hậu quân (rear army). Each division was commanded by a Ngũ quân Đô Thống (French: maréchal, rank 1A). The maréchal of the trung quân was the commander-in-chief held responsible for the defensive of the royal city of Hue and surrounding areas, while other four armies Below a maréchal were Thống chế and Đề đốc (general, rank 2A), each commanded a doanh (2,500 men). Under a general, there were Lãnh binh (French: colonel, rank 3A/B), commanded vệ (each had 500 soldiers, French: bataillon) and Quản cơ (French: chef de régiment provincial, rank 4A/B), commanded cơ (each also had 500 soldiers, French: régiment) Each vệ and cơ had ten đội (50 soldiers) headed by a Cai đội (French: capitaine, rank 5A/B), assisted by a trưởng suất đội (French: lieutenant) and a thợ lại (company clerk). The smallest army unit were squads thập (9 soldiers, French: escouade), commanded by a Chánh đội trưởng suất thập/đội trưởng officer (French: sergent, rank 7A/B) and had a bếp soldier (French: caporal).[7] A normal soldier (lính cơ) during the reign of Minh Mạng received the minimum monthly salary of one quan or a string of cash coins (about 500 coins), which would purchase about 48.9 pounds (22 kilograms) of husked rice, which was only half of what a tenant peasant earned per month.[8]

The soldiers wore red tunics, while officers dressed like common gentlemen with a black aodai, even during wartime.[9] Each officer often carried a sword or a pistol. Regulations said during ceremonies, the officers had to wear green silk robes, specific animal decorations based upon ranks, and black silk turbans. Known animal texture decorations are listed below:[10]

- Unicorn for marshals

- "fantastic animals" for generals

- Lion for imperial colonels

- Tiger for colonels

- Black panther for captains

- Bear for lieutenants

- Leopard for senior sergǣnts

- Seahorse for sergǣnts

- Rhinoceros for corporals

The size of the provincial army depended on each period. During the reign of Gia Long, the provincial army numbered up to 150,000 to 200,000 men. During the reign of Minh Mang, it was 36,000 to 60,000.[11] During a later period under Thieu Tri and Tu Duc (1841–1883), the army was practically undisciplined 32,000 peasant-soldiers, with only 10% of them armed with muskets or rifles. The rest had to use spears or knives. Training was very limited. When the French attacked Saigon, there were about 7,000 Vietnamese combatants instead of the reported 12,000, and there weren't reserves and mobilization to deal with the casualties rather than local recruits.[12] The artillery organ had only 200 cannons, which almost were exceedingly heavy, outdated, and no match to European guns.[13]

Tirailleurs[]

During the French conquest, thousands of Vietnamese and Muong volunteers included many Christians formed auxiliaries and professional military groups known as tirailleurs that helped the French to suppress and subjugate rebellions, campaigns in Tonkin, Cambodia, and Laos.[14] The majority of these tirailleur units were commanded by French officers. Each tirailleur soldier was armed with a musket, and later a chassepot rifle and bayonet.[15]

[]

The navy was part of the Vietnamese military and its bureaus. J. H. Moor in his 1837 account reported that in 1823, the Nguyen navy consisted of 50 schooners with 14 guns, 80 gunboats (sloop-of-war), 100 vessels, 300 galleys with 80 to 100 rowing oars, and 500 galleys with 40 to 80 oars.[16] Another two hundred galleys owned by the emperor in Hue, "were built based on European and European-Vietnamese mixed styles, with fourteen guns on each."[17] John White, an American lieutenant and naval captain that visited Saigon in 1819, had once commented: "Cochinchina [Southern Vietnam] is perhaps, of all the powers in Asia, the best adapted to maritime adventure."[18][19]

Later during the reign of Thieu Tri and Tu Duc, Vietnamese naval superiority was no longer. Lacking a view that interested in the military, and financial support, the court quickly abandoned the great navy. Gunships gradually were transformed into trading ships to serve the failing economy.[20] Technology drastically falling behind Europe. In 1880, the Vietnamese royal navy had seven corvettes, 300 junks, two old British steamers, and five French HP boats, all were later absorbed by the French Indochinese navy.[21]

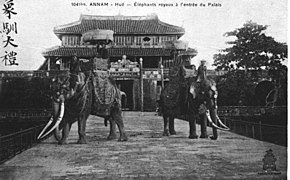

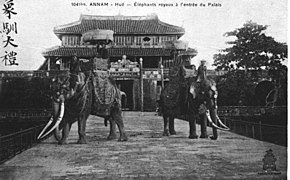

War elephants[]

War elephants were recruited in the military like the previous Vietnamese military. Established by Gia Long in 1803, the Royal Elephant Corp Elephants of the Guard (Tượng Quân) served the emperor's escort when he needs. Commanded by a Chưởng tượng quân, the corp was divided into fives regiments (515 men per regiment), each regiment had five companies, each company had four squads. The Elephants of the Guard later was renamed to Elephants of the Inner Guard (Thị Nội Tượng) in 1815, and then in 1829 it became known as the Elephants of the Capital (Kinh Tượng). The local army also had its own elephant corps.[22] In 1840s, the Vietnamese employed about 280 elephants with 2,340 men of 55 elephant companies in military service.[23]

Vietnamese war elephants were relatively small, ranging from 1.8m (5.9 ft) to 2.8m (9.2 ft) in height. Each elephant carries a red hemp bridle, a howdah, a chain crupper, belly-strap, a silk flag, two leather belts, 30 arrows, 30 javelins, an iron hook. The howdah usually depicted a lion or a dragon.[24]

The last war elephant battle was raged on 5 July 1885, when French troops of 11th battalion chasseurs a Pied were charged by Vietnamese war elephants from within the Hue citadel, which forced the French to retreat to an embankment where they fire back in cover and eventually drove the elephants back.[25]

Citadels[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (August 2021) |

Gallery[]

Elephant army.

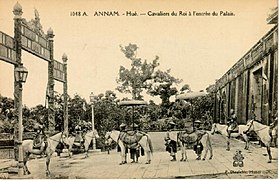

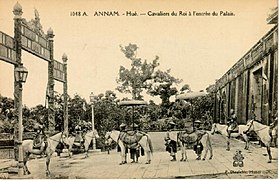

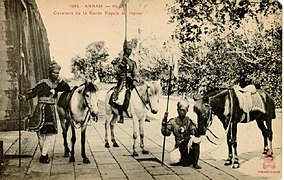

Royal guard of Palace.

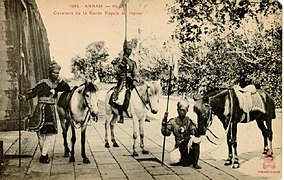

cavalier soldier of Huế.

Royal guard of Huế.

Royal guard of Palace.

Footnotes[]

- ^ Hoàng Cơ Thụy. Việt sử khảo luận. Paris: Nam Á, 2002. Page 976.

- ^ Karl Hack and Tobias Rettig. (2006). Colonial armies in Southeast Asia. New York: Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-33413-6.

- ^ De Rode Leeuw - Armorial of Vietnam § Imperial Guard by Hubert de Vries. Retrieved: 16 August 2021.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 163.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 195.

- ^ Bezacier (1941), p. 332.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 176.

- ^ Choi (2004a), p. 171.

- ^ Gutzlaff (1849), p. 141.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 196.

- ^ Gutzlaff (1849), p. 140.

- ^ Chapuis (2000), p. 14.

- ^ McLeod (1991), p. 47.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 202.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 203.

- ^ Li (2004b), p. 127.

- ^ White (1824), p. 264.

- ^ White (1824), p. 265.

- ^ Li (2004b), p. 120.

- ^ Li (2004b), p. 131.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 184.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 180.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 182.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 181.

- ^ Heath (2003), p. 183.

Sources[]

- Bezacier, Louis (1941), L'Art et les constructions militaires annamites, Hanoi: Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hue No 4 Oct-Dec 1941

- Chapuis, Oscar (2000). The Last Emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31170-6.

- Choi, Byung Wook (2004a), Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response, SEAP Publications, ISBN 978-1-501-71952-3

- ——— (2004b), "The Nguyen dynasty's policy toward Chinese on the Water Frontier in the first half of the Nineteenth Century", in Nola, Cooke (ed.), The Water Frontier, Singapore University Press, pp. 85–99

- Crawfurd, John (1828). Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China: Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of Those Kingdoms. H. Colburn.

- Gutzlaff, Karl (1849). "Geography of the Cochin-Chinese Empire". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 19: 85–143. doi:10.2307/1798088. JSTOR 1798088.

- Heath, Ian (2003) [1998]. Armies of the Nineteenth Century: Burma and Indo-China. Foundry Books. ISBN 978-1-90154-306-3.

- Li, Tana (2004a), "The Water Frontier: In Introduction", in Nola, Cooke (ed.), The Water Frontier, Singapore University Press, pp. 1–20, ISBN 978-0-74253-082-9

- ——— (2004b), "Ships and ship building in the Mekong delta, 1750–1840", in Nola, Cooke (ed.), The Water Frontier, Singapore University Press, pp. 119–135

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese response to French intervention, 1862–1874. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93562-0.

- Rivas, Manuel de (1859). Idea del imperio de Annam, ó de los reinos unidos de Tunquin y Cochinchina. Imprenta y Libreria de E. Eusebio Aguado.

- Rhins, Jules-Léon Dutreuil de (1879). Le royaume d'Annam et les Annamites: journal de voyage. E. Plon.

- White, John (1824). A Voyage to Cochinchina. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

- Woodside, Alexander (1988) [1971]. Vietnam and the Chinese model: a comparative study of Vietnamese and Chinese government in the first half of the nineteenth century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-93721-X.