French assistance to Nguyễn Ánh

| Foreign alliances of France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

French assistance to Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (name later changed to Gia Long), the future Emperor of Vietnam and the founder of the Nguyễn Dynasty, covered a period from 1777 to 1820. From 1777, Mgr Pigneau de Behaine, of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, had taken to protecting the young Vietnamese prince who was fleeing from the offensive of the Tây Sơn. Pigneau de Behaine went to France to obtain military aid, and secured a France-Vietnam alliance that was signed through the 1787 Treaty of Versailles between the king of France, Louis XVI, and Prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh. As the French regime was under considerable strain at the eve of the French Revolution, France was unable to follow through with the application of the treaty. However, Mgr Pigneau de Behaine persisted in his efforts and, with the support of French individuals and traders, mounted a force of French soldiers and officers that would contribute to the modernization of the armies of Nguyễn Ánh, making possible his victory and his reconquest of all of Vietnam by 1802. A few French officers would remain in Vietnam after the victory, becoming prominent mandarins. The last of them left in 1824 following the enthronement of Minh Mạng, Gia Long's successor. The terms of the 1787 Treaty of Alliance would still remain one of the justifications of French forces when they demanded the remittance of Đà Nẵng in 1847.

Protection of Nguyễn Ánh[]

The French first intervened in the dynastic battles of Vietnam in 1777 when 15-year-old Prince Nguyễn Ánh, fleeing from an offensive of the Tây Sơn, received shelter from Mgr Pigneau de Behaine in the southern Principality of Hà Tiên.[1] Pigneau de Behaine and his Catholic community in Hà Tiên then helped Nguyễn Ánh take refuge in the island of .[1]

These events created a strong bond between Nguyễn Ánh and Pigneau de Behaine, who took a role of protector over the young prince. Following this ordeal, Nguyễn Ánh was able to recapture Saigon in November 1777 and the whole of Cochinchina, and took the title of Commander in Chief in 1778.

Intervention in the Cambodian conflict (1780–1781)[]

In neighbouring Cambodia, a pro-Cochinchinese revolt erupted to topple the pro-Siam king Ang Non. In 1780, the Cochinchinese troops of Nguyễn Ánh intervened, and Pigneau helped them obtain weapons from the Portuguese. The Bishop was even accused by the Portuguese of manufacturing weapons for the Cochinchinese, especially grenades, a new weapon for Southeast Asia.[2] Pigneau de Behaine also organized the supply of three Portuguese warships for Nguyễn Ánh.[3] In his activities, Pigneau was supported by a French adventurer, Manuel.[3] Contemporary witnesses clearly describe Pigneau's military role:

"Bishop Pierre Joseph Georges, of French nationality, has been chosen to deal with certain matters of war"

— J. da Fonceca e Sylva, 1781.[4]

1782-1783-1785 Tây Sơn offensives[]

The French adventurer Manuel, in the service of Mgr Pigneau, took part in the battles against the 1782 offensive of the Tây Sơn. He fought commanding a warship against the Tây Sơn in the Saigon River, but he blew himself up with his warship rather than surrender to the more numerous Tây Sơn navy.[5] In October 1782, Nguyễn Ánh was able to recapture Saigon, only to be expelled again by the Tây Sơn in March 1783.

In March 1783, the Nguyễn were again defeated, and Nguyễn Ánh and Pigneau fled to the island of Phú Quốc. They had to escape again when their hideout was discovered, being chased from island to island until they reached Siam. Pigneau de Behaine visited the Siamese court in Bangkok end 1783.[6] Nguyễn Ánh also reached Bangkok in February 1784, where he obtained that an army would accompany him back to Vietnam.[7] In January 1785 however, the Siamese fleet met with disaster against the Tây Sơn in the Mekong.[7]

Nguyễn Ánh again took refuge with the Siamese court, and again tried to obtain help from the Siamese.[8] Nguyễn Ánh also resolved to obtain any help he could from Western countries.[9] He asked Pigneau to appeal for French aid, and allowed Pigneau to take his five-year-old son Prince Cảnh with him. Pigneau also tried to obtain help from Manila, but the party of Dominicans he sent was captured by the Tây Sơn.[9] From Pondicherry, he also sent a request for help to the Portuguese Senate in Macao, which would ultimately lead to the signature of a Treaty of Alliance between Nguyễn Ánh and the Portuguese on 18 December 1786 in Bangkok.[10]

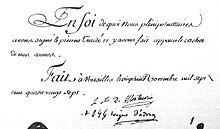

Treaty of Versailles (1787)[]

Mgr Pigneau de Behaine arrived in Pondicherry with Prince Cảnh in February 1785.[11] The French administration in Pondicherry, led by the interim Governor , successor of Bussy, seconded by Captain d'Entrecasteaux, was resolutely opposed to intervening in southern Vietnam, stating that it was not in the national interest. In July 1786, Pigneau was allowed to travel to France to ask the royal court directly for assistance. News of his activities reached Rome where he was denounced by the Spanish Franciscans, and offered Prince Cảnh and his political mandate to the Portuguese. They left Pondicherry for France in July 1786.[12] which they reached in February 1787.[13]

Arriving in February 1787 with the child prince Canh at the court of Louis XVI in Versailles,[14] Pigneau had difficulty in gathering support for a French expedition to install Nguyễn Ánh on the throne. This was due to the poor financial state of the country prior to the French Revolution.

Eventually, he was able to seduce the technicians of military action with his precise instructions as to the conditions of warfare in Indochina and the equipment for the proposed campaign. He explained how France would be able to "dominate the seas of China and of the archipelago." The party met with King Louis XVI, Minister of the Navy de Castries and Minister of Foreign Affairs Montmorin on May 5 or 6, 1787.[15] Prince Cảnh created a sensation at the court of Louis XVI, leading the famous hairdresser Léonard to create a hairstyle in his honour "au prince de Cochinchine".[16] His portrait was made in France by Maupérin, and is now on display at the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères in Paris. Prince Cảnh dazzled the Court and even played with the son of Louis XVI, Louis-Joseph, Dauphin of France, who was about the same age.[17][18]

By November, his constant pressure had proved effective. On 21 November 1787, the Treaty of Versailles was concluded between France and Cochinchina in Nguyễn Ánh's name. Four frigates, 1650 fully equipped French soldiers and 250 Indian sepoys were promised in return for Pulo Condore and harbour access at Tourane (Da Nang). De Fresne was supposed to be the leader of the expedition.[20]

The French government, on the eave of the French Revolution, was in tremendous financial trouble,[21] and saw its position weakened following the outbreak of civil war in Holland, theretofore a strategic ally in Asia.[22] These elements strongly dampened its enthusiasm for Pigneau's plan between his arrival and the signature of the Treaty in November.[23] A few days after the treaty was signed, the foreign minister sent instructions on 2 December 1787 to the Governor of Pondicherry Thomas Conway, which left the execution of the treaty to his own appreciation of the situation in Asia, stating that he was "free not to accomplish the expedition, or to delay it, according to his own opinion"[24]

Military assistance (1789–1802)[]

The party would leave France in December 1787 on board the Dryade,[25] commanded by M. de Kersaint and accompanied by the Pandour, commanded by M. de Préville. They would again stay in Pondicherry from May 1788 to July 1789.[26] The Dryade was ordered by Conway to continue to Poulo Condor to meet with Nguyễn Ánh and deliver him 1,000 muskets bought in France and Father , a Cochinchinese missionary devoted to Mgr Pigneau.

However, Pigneau found the governor of Pondicherry unwilling to further fulfill the agreement. Although the Royal Council had already decided in October 1788 to endorse Conway, Pigneau was not informed until April. Pigneau was forced to use funds raised in France and enlist French volunteers. Pigneau was unaware of this duplicity. He defiantly noted: "I shall make the revolution in Cochinchina alone." He rejected an offer from the English, and raised money from French merchants in the region.

Conway finally provided two ships to Pigneau, the Méduse, commanded by Rosily,[27] and another frigate to bring Pigneau back to Cochinchina.[28]

Pigneau used the funds he had accumulated to equip two more ships with weapons and ammunition, which he named the Long phi ("Le Dragon"), commanded by Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, and the Phung phi ("Le Phénix"), commanded by Philippe Vannier, and he hired volunteers and deserters.[27] Jean-Marie Dayot deserted the Pandour and was put in charge of supplies, transporting weapons and ammunitions on his ship the St. Esprit. Rosily, who had been commanding the Méduse deserted with 120 of his men, and was put in charge of recruitments.[27]

Pigneau's expedition left for Vietnam on June 19, 1789, and arrived at Vũng Tàu on 24 July 1789.[27] The forces gathered by Pigneau helped consolidate southern Vietnam and modernized its army, navy and fortifications. At the highest point, the total French military presence in Vietnam seems to have consisted in about 14 officers and about 80 men.[29]

Land forces[]

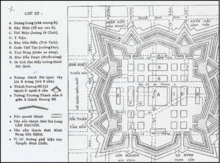

Olivier de Puymanel, a former officer of the Dryade who has deserted in Poulo Condor, built in 1790 the Citadel of Saigon and in 1793 the Citadel of Dien Khanh according to the principles of Vauban. He also trained Vietnamese troops in the modern use of artillery, and implemented European infantry methods in the Vietnamese army of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh.[30]

In 1791, the French missionary Boisserand demonstrated to Nguyễn Ánh the usage of balloons and electricity. Puymanel suggested that these be used to bombard cities under siege such as Qui Nhơn, but Nguyễn Ánh refused to use these contraptions.[31]

In 1792, Olivier de Puymanel was commanding an army of 600 men who had been trained with European techniques.[31] Puymanel is said to have trained the 50,000 men of Nguyen's army.[32] French bombs were used at the siege of Qui Nhơn in 1793.[33]

From 1794, Pigneau himself participated to all the campaigns, accompanying Prince Cảnh. He organized the defense of Dien Khanh when it was besieged by a vastly more numerous Tây Sơn army in 1794.[34]

[]

French Navy officers such as Jean-Marie Dayot and Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau were used to train the navy. By 1792, a large Navy was built, with two European warships and 15 frigates of composite design.[35]

In 1792, Dayot forced the harbour of Qui Nhơn, opening the way to the Cochinchinese fleet which then defeated the Tây Sơn fleet.[36]

In 1793, Dayot led a raid in which 60 Tây Sơn galleys were destroyed.[36]

In 1799, the Englishman Berry witnessed the departure of the Nguyễn fleet, composed of three sloops of war commanded by French officers, each of them with 300 men, 100 galleys with troops, 40 war junks, 200 smallers ships, and 800 transport boats.[35]

Jean-Marie Dayot also did considerable hydrographic work, making numerous maps of the Vietnamese coast, which were drawn by his talented brother.[37]

Arms trade[]

Nguyễn Ánh and Mgr Pigneau de Behaine also relied on French officers to obtain weapons and ammunitions throughout Asia through trade.[38]

In 1790, Jean-Marie Dayot was sent by Nguyễn Ánh to Manila and Macao to trade for military supplies.[38]

Olivier de Puymanel, after having built several fortresses for Nguyễn Ánh, focused on the trading of weapons from 1795. In 1795 and 1796, he made two trips to Macao, where he sold Cochinchinese agricultural products in exchange for weapons and ammunitions. In 1795 he also travelled to Riau to trade rice received from Nguyễn Ánh. In 1797–98, he travelled to Madras to obtain the remittance of the Armida, a warship belonging to Barizy, in the service of Nguyễn Ánh, which had been captured by the East India Company in 1797.[38]

Barizy, who had entered the service of Nguyễn Ánh in 1793, also sailed to Malacca and Pulau Pinang to exchange Cochinchinese products against weapons. His ship, the Armida was captured by the East India Company, but finally returned. In 1800, Nguyễn Ánh sent him to trade with Madras to obtain weapons.[38] According to one missionary, he was:

"Agent and deputy of the king of Cochinchina with the various governors of India, in order to obtain all that he needed".

— Letter by , 24 April 1800.[39]

Death of Pigneau de Behaine (1799)[]

Pigneau died at the siege of Qui Nhơn in October 1799. Pigneau de Behaine was the object of several funeral orations on behalf of emperor Gia Long and his son Prince Cảnh.[40] In a funeral oration dated 8 December 1799, Gia Long praised Pigneau de Behaine's involvement in the defense of the country, as well as their personal friendship:

"(...) Pondering without end the memory of his virtues, I wish to honour him again with my kindness, his Highness Bishop Pierre, former special envoy of the kingdom of France mandated to obtain a sea-based and land-based military assistance sent by decree by warships, him, this eminent personality of the Occident received as a guest of honour at the court of Nam-Viet (...) Although he went to his own country to address a plea for help and rally the opinion in order to obtain military assistance, he was met with adverse conditions midway through his endeavour. At that time, sharing my resentment, he decided to act like the men of old: we rather rallied together and outshone each other in the accomplishment of duty, looking for ways to take advantage of opportunities to launch operations (...) Everyday intervening constantly, many times he marvelously saved the situation with extraordinary plans. Although he was preoccupied with virtue, he did not lack humour. Our agreement was such that we always desired to be together (...) From the beginning to the end, we were but one heart (...)"

— Funeral oration of emperor Gia Long to Pigneau de Behaine, 8 December 1799.[41]

The French forces in Vietnam continued the fight without him, until the complete victory of Nguyễn Ánh in 1802.

Qui Nhơn battle (1801)[]

The Tây Sơn suffered a major naval defeat at Qui Nh��n in February 1801. The French took an active part in the battle.[42] Chaigneau described the battle in a letter to his friend Barizy:

"We have just burnt all the navy of the enemies, so that not even the smallest ship escaped. This was the bloodiest fight the Cochinchinese had ever seen. The enemies fought to the death. Our people behaved in a superior manner. We have many dead and wounded, but this is nothing compared to the advantages the king is receiving. Mr Vannier, Forsanz and myself were there, and came back safely. Before seeing the enemy navy, I used to despise it, but I assure you this was misconceived, they had vessels with 50 to 60 cannons.

— Letter from Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau to Barizy, 2 March 1801.[43]

On June 5, 1801, Nguyen left with his fleet for the north, and ten days later succeeded in capturing Huế.[44] On 20 July 1802, Nguyễn Ánh captured Hanoi and thus completed his reconquest of Vietnam.[45]

Continued French presence in Vietnam[]

Once Nguyễn Ánh became emperor Gia Long, several Frenchmen remained at the court to become mandarins, such as Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau.[46] Chaigneau received the title of truong co, together with Philippe Vannier, de Forsans and Despiau, meaning second-class second-degree military mandarins, and later received the title of Grand Mandarin once Gia Long became emperor, with personal escorts of 50 soldiers.[47]

Several also married into a Vietnamese Catholic mandarin family, such as Chaigneau, Vannier or Laurent Barizy.[48]

The results of these French efforts at the modernization of Vietnamese forces were attested by John Crawfurd, who visited Huế in 1822:

"In Cochin China a military organization has been established through the example and assistance of the French refugees in the country which has at least a very imposing appearance. The army consists of about forty thousand men uniformely clothed in British broad cloth, officered after the European manner and divided up into battalions under brigades. The park of artillery is numerous and excellent."

— Narrative of the Crawfurd mission....[49]

With the death of Gia Long and the advent of Minh Mạng, relations strained considerably, and French advisors left the country. The last two of them, Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau and Philippe Vannier left Vietnam for France in 1824, together with their Vietnamese families.

Seclusion and persecutions[]

Only Catholic missionaries, mostly members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, remained in Vietnam, although their activities were soon prohibited and they became persecuted.

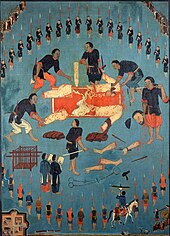

In Cochinchina, the Lê Văn Khôi revolt (1833–1835) united Vietnamese Catholics, missionaries and Chinese settlers in a major revolt against the ruling emperor, in which they were defeated. Persecutions would follow, leading to the killing of numerous missionaries such as Joseph Marchand in 1835, Jean-Charles Cornay in 1837, or Pierre Borie in 1838, as well as local Catholics.

In 1847, French warships under and Charles Rigault de Genouilly demanded that persecutions cease, and that Da Nang be remitted to them in application of the 1787 Treaty of Versailles. The French sank the Vietnamese fleet in Da Nang in the Bombardment of Đà Nẵng (1847), and negotiation with Emperor Thiệu Trị broke down.[50]

Persecutions of Catholics, combined with French desire for colonial expansion, would trigger ever stronger military interventions from France. The dispatch of an expeditionary force under Rigault de Genouilly would mark the return of the French military on Vietnamese soil, with the Siege of Đà Nẵng (1858) and the Capture of Saigon (1859), origin of the establishment of French Indochina.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.77

- ^ Mantienne, p.78

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.81

- ^ Quoted in Mantienne, p.79–80

- ^ Mantienne, p.81–82

- ^ Mantienne, p.83

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.84

- ^ Mantienne, pp.84–85

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.85

- ^ Mantienne, p.87

- ^ Mantienne, p.84, p.200

- ^ Mantienne, p.92

- ^ Mantienne, p.93

- ^ Dragon Ascending by Henry Kamm p.86-87

- ^ Mantienne, p.96

- ^ Viet Nam by Nhung Tuyet Tran, Anthony Reid, p.293

- ^ "He dazzled the Louis XVI court at Versailles with Nguyen Canh, ... dressed in red and gold brocade, to play with the Dauphin, the heir apparent." in The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies by Sheridan Prasso, p.40

- ^ "The Dauphin, about his age, played with him." French Policy and Developments in Indochina – Page 27 by Thomas Edson Ennis

- ^ Mantienne, pp.97, 204

- ^ Mantienne, p.97

- ^ Mantienne, p.106

- ^ Mantienne, p.104

- ^ Mantienne, p.103-108

- ^ Mantienne, p.98. Original French: "il était "maître de ne point entreprendre l'opération ou de la retarder, d'après son opinion personnele""

- ^ Mantienne, pp.109–110

- ^ Mantienne, p.110

- ^ a b c d Chapuis, p.178

- ^ "Conway finally provided the frigate Meduse and another vessel to repatriate the mission" in The Roots of French Imperialism in Eastern Asia – Page 14 by John Frank Cady 1967 [1]

- ^ Mantienne, p.152

- ^ McLeod, p.11

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.153

- ^ Colonialism by Melvin Eugene Page, Penny M. Sonnenburg, p.723

- ^ Mantienne, p.132

- ^ Mantienne, p.135

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.129

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.130

- ^ Mantienne, p.156

- ^ a b c d Mantienne, pp.158–159

- ^ Quoted in Mantienne, p.158. Original French:"Agent et député du roi de Cochinchine auprès des différents gouverneurs etc... de l'Inde, pour lui procurer tout ce dont il a besoin"

- ^ Mantienne, pp.219–228

- ^ In Mantienne, p.220. Original French (translated by M.Verdeille from the Vietnamese): "Méditant sans cesse le souvenir de ses vertus, je tiens à honorer à nouveau de mes bontés, sa grandeur l'évèque Pierre, ancien envoyé spécial du royaume de France mandaté pour disposer d'une assistance militaire de terre et de mer dépèchée par décret par navires de guerre, [lui] éminente personnalité d'Occident reçue en hôte d'honneur à la cour du Nam-Viet (...) Bien qu'il fut allé dans son propre pays élever une plainte et rallier l'opinion en vue spécialement de ramener des secours militaires, à mi-chemin de ses démarches survinrent des événements adverses à ses intentions. Alors, partageant mes ressentiments, il prit le parti de faire comme les anciens: plutôt nous retrouver et rivaliser dans l'accomplissement du devoir, en cherchant le moyen de profiter des occasions pour lancer des opérations (...) Intervenant constamment chaque jour, maintes fois il a merveilleusement sauvé la situation par des plans extraordinaires. Tout en étant préoccupe de vertu, il ne manquait pas de mots d'humour. Notre accord était tel que nous avions toujours hâte d'être ensemble (...) Du début a la fin, nous n'avons jamais fait qu'un seul coeur."

- ^ Mantiene, p.130

- ^ Quoted in Mantienne, p.130

- ^ Pirates of the South China Coast, 1790–1810 Murray – Page 47

- ^ Pirates of the South China Coast, 1790–1810 Murray – Page 48

- ^ Tran, p.16

- ^ McLeod, p.20

- ^ Tran and Reid, p.207

- ^ In Alastair Lamb The Mandarin Road to old Huế, p.251, quoted in Mantienne, p.153

- ^ Chapuis, p.194

References[]

- Chapuis, Oscar (2000). The Last Emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31170-6.

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese response to French intervention, 1862–1874. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93562-0.

- Mantienne, Frédéric (1999). Monseigneur Pigneau de Béhaine. 128 Rue du Bac, Paris: Editions Eglises d'Asie. ISBN 2-914402-20-1. ISSN 1275-6865.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Salles, André (2006). Un Mandarin Breton au service du roi de Cochinchine. Les Portes du Large. ISBN 2-914612-01-X.

- Tran, My-Van (2005). A Vietnamese royal exile in Japan: Prince Cường Để (1882–1951). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29716-8.

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet; Reid, Anthony (2006). Việt Nam: borderless histories. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-21774-4.