First Madagascar expedition

| First Madagascar expedition (1883–1885) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Hova Wars | |||||||

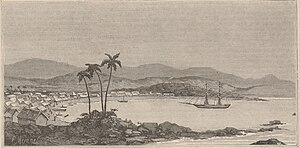

Tamatave, bombarded and occupied by the French under Admiral Pierre, on 11 June 1883. Le Monde Illustré, 1883. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 cruisers (Flore, Forfait) 1 scout ship (Vaudreuil) 1 aviso (Boursait) 1 gunboat (Pique) 1 aviso transport (Nièvre) | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

| unknown | |||||||

The First Madagascar expedition was the beginning of the Franco-Hova War and consisted of a French military expedition against the Merina Kingdom on the island of Madagascar in 1883. It was followed by the Second Madagascar expedition in 1895.

British influence[]

Following their capture of Mauritius from the French in 1810 during the Napoleonic Wars, with ownership confirmed by the 1814 Treaty of Paris, the British saw Madagascar as a natural expansion of their influence in the Indian Ocean.[1] The Merina King, Radama I, managed to unite Madagascar under one rule, benefiting from British weapons and military instructors.[1] He signed treaties with the British, allowing Protestant missionaries and outlawing the slave trade.[2]

When Queen Ranavalona I took power in 1828, relationships with foreign powers gradually soured. By the mid-1830s, nearly all foreigners had chosen to leave or were expelled, and British influence was largely suppressed.[1][2] An exception, the Frenchman Jean Laborde, was able to remain in the island to build foundries and an armament industry.

Meanwhile, the Queen's son Prince Rakoto (future King Radama II) had been under the influence of French nationals at Antananarivo. In 1854, a letter destined for Napoleon III that he dictated and signed was utilized by the French government as a basis for future invasion of Madagascar.[2] He further signed the Lambert Charter on 28 June 1855, a document that granted Frenchman Joseph-François Lambert numerous lucrative economic privileges on the island,[2] including exclusive right to all mining and forestry activities, and exploitation of unoccupied land, in exchange for a 10% fee to the Merina monarchy.[2] A coup to topple the Queen and replace her by her son was also planned, in which Laborde and Lambert were involved. Upon the death of the queen, her son took over as King Radama II in 1861, but he only ruled two years before ending by an assassination attempt. This assassination was treated as successful at the time, although later evidence suggests Radama survived the attack and lived to old age as a regular citizen outside the capital. He was succeeded to the throne by his apparent widow Rasoherina.

The Prime Minister Rainivoninahitriniony revoked the Lambert Treaty in 1863. From 1864, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony endeavored to modernize the state by putting an end to slavery in 1877, modernizing the legal system in 1878 and setting up a new constitution in 1881.[3] Under the anglophile Rainilaiarivony, British influence grew considerably in the economic and religious fields.[1]

Growing French interests[]

In the early 1880s however, the French colonial faction, the right-wing Catholic lobby and Réunion parliamentarians all advocated an invasion of Madagascar in order to suppress British influence there.[3] The non-respect of the Lambert Charter and the letter to Napoleon III were used by the French as the pretext to invade Madagascar in 1883.[2] Various disputes also helped trigger the intervention: the minority Sakalavas remained faithful to a French protectorate in the north of the island, a French national was killed in Antananarivo, and the Merina placed an order for the French flag to be replaced by the Madagascar flag in French concessions.[1] This triggered the first phase of the Franco-Hova War.

Expedition[]

The decision was taken to send the naval division of Admiral .[1] The French under Admiral Pierre[4] bombarded the northwestern coast and occupied Majunga in May 1885.[5] A column brought an ultimatum to Antananarivo, asking for recognition of French rights in northeastern Madagascar, a French protectorate over the Sakalava, recognition of French property principles and an indemnity of 1,500,000 francs.[1][5]

When the ultimatum was refused, France bombarded the east coast, occupied Toamasina, and arrested the English missionary Shaw.[3][5] Meanwhile, Queen Ranavalona II died, as did Admiral Pierre, who succumbed to the fatigue of the campaign.[1] Admiral Pierre was replaced by Admiral Galiber, and then Counter-Admiral Miot.[1]

Aftermath[]

A Treaty was signed in December 1885, the French interpreting it as a Protectorate Treaty, while Queen Ranavalona III and Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony denied it.[3] The Treaty included the acceptance of a French resident in Antananarivo and the payment of an indemnity of 10 million.[1]

The Treaty however remained without effect, and would lead to the Second Madagascar expedition in 1895, which resulted in French colonization of Madagascar.[1]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Randier, Jean (2006), La Royale, La Falaise: Babouji, p. 400, ISBN 2-35261-022-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Van Den Boogaerde, Pierre (2008), Shipwrecks of Madagascar, AEG Publishing Group, p. 7, ISBN 978-1-60693-494-4.

- ^ a b c d Boahen, A. Adu (1 January 1990), Africa under colonial domination 1880-1935, p. 108, ISBN 978-0-85255-097-7.

- ^ Johnston, Harry Hamilton (1969), A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-543-95979-9.

- ^ a b c Priestley, Herbert Ingram (26 May 1967), France overseas: a study of modern imperialism, p. 305, ISBN 978-0-7146-1024-5.

- Conflicts in 1883

- Conflicts in 1884

- Conflicts in 1885

- 1883 in Africa

- Madagascar expeditions

- Military expeditions

- Expeditions from France