Second French intervention in Mexico

| Second French intervention in Mexico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

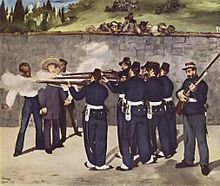

Clockwise from left: French assault during the Second Battle of Puebla; French cavalry seize the Republican flag during the Battle of San Pablo del Monte; The Execution of Emperor Maximilian by Édouard Manet | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by |

Initially supported by Supported by | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Supported by |

Initially supported by Supported by | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

31,962 killed 8,304 wounded 33,281 captured 11,000 executed[12] |

14,000 killed[12] show

Details | ||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Second French Intervention in Mexico (Spanish: Segunda intervención Francesa en México), 1861–1867;[15] was an invasion of Mexico, launched in late 1861, by the Second French Empire (1852–1870), aiming to establish in Mexico a regime favorable to French interests.

On 31 October 1861, France, the United Kingdom, and Spain agreed to the Convention of London, a joint effort to ensure that debt repayments from Mexico would be forthcoming. On 8 December 1861, the three navies disembarked their troops at the port city of Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mexico. When the British and the Spanish discovered that France had an ulterior motive and unilaterally planned to seize Mexico, they peacefully negotiated an agreement with Mexico to settle the debt issues. Simultaneously, Britain and Spain withdrew from the military coalition agreed to in London, and recalled their forces from Mexico. The subsequent French invasion took Mexico City and created the Second Mexican Empire (1861–1867), a client state of the French Empire. Many nations acknowledged the political legitimacy of the newly created nation state.[16]

In Mexican politics, the French intervention allowed active political reaction against the liberal policies of social and socio-economic reform of president Benito Juárez (1858–1872), thus the Mexican Catholic Church, upper-class conservatives, much of the Mexican nobility, and some Native American communities welcomed and collaborated with the French empire's installation of Maximilian von Habsburg as Emperor of Mexico.[17] In European politics, the French intervention in Mexico reconciled the Second French Empire and the Austrian Empire, whom the French had defeated in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859. French imperial expansion into Mexico counterbalanced the geopolitical power of the Protestant Christian United States, by developing a powerful Catholic empire in Latin America, and the exploitation of the mineral wealth of the Mexican north-west. After much guerrilla warfare that continued after the Capture of Mexico City in 1863, the French Empire withdrew from Mexico and abandoned the Austrian emperor of Mexico; subsequently, the Mexicans executed Emperor Maximilian I, on 19 June 1867, and restored the Mexican Republic.[17]

Background[]

The French intervention in Mexico, initially supported by the United Kingdom and Spain, was a consequence of Mexican President Benito Juárez's imposition of a two-year moratorium of loan-interest payments from July 1861 to French, British, and Spanish creditors. To extend the influence of Imperial France, Napoleon III instigated the intervention in Mexico by claiming that the military adventure was a foreign policy commitment to free trade. The establishment of a European-derived monarchy in Mexico would ensure European access to Mexican resources, particularly French access to Mexican silver. To realize his ambitions without interference from other European nations, Napoleon III of France entered into a coalition with the United Kingdom and Spain.

French invasion[]

The fleets of the Tripartite Alliance arrived at Veracruz between 8 and 17 December 1861, intending to pressure the Mexican government into settling its debts.[18] The Spanish fleet seized San Juan de Ulúa and subsequently the capital Veracruz[18] on 17 December. The European forces advanced to Orizaba, Cordoba and Tehuacán, as they had agreed in the Convention of Soledad.[18] The city of Campeche surrendered to the French fleet on 27 February 1862, and a French army, commanded by Charles de Lorencez, arrived on 5 March. The Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Manuel Doblado met with the Spanish general Juan Prim (who was the nominal commander of the tripartite alliance) and explained to him the country's economic complications and persuaded him that the suspension of the debts was only going to be temporary. For the governments of Spain and Great Britain this explanation was sufficient, and along with their realisation of the French ambition to conquer Mexico, the two governments made the decision to peacefully withdraw their forces on 9 April, with the last British and Spanish troops leaving on 24 April without a shot being fired by either army. In May, the French man-of-war Bayonnaise blockaded Mazatlán for a few days.

Mexican forces commanded by General Ignacio Zaragoza managed to win an unexpected victory against the French army in the Battle of Puebla on 5 May 1862 (commemorated by the Cinco de Mayo holiday) halting the French advance for some time. The pursuing Mexican army was contained by the French at Orizaba, Veracruz, on 14 June. More French troops arrived on 21 September, and General Bazaine arrived with French reinforcements on 16 October. The French occupied the port of Tampico on 23 October, and unopposed by Mexican forces took control of Xalapa, Veracruz on 12 December.[19]

The Battle of Puebla, 5 May 1862

Capture of Mexico City by the French[]

The French bombarded Veracruz on 15 January 1863. Two months later, on 16 March, General Forey and the French Army began the siege of Puebla.

On 30 April, the French Foreign Legion earned its fame in the Battle of Camarón (or Camerone in French), when an infantry patrol unit of 62 soldiers and three officers, led by the one-handed Captain Jean Danjou, was attacked and besieged by Mexican infantry and cavalry units numbering three battalions, about 3000 men. They were forced to make a defence in a nearby hacienda. Danjou was mortally wounded at the hacienda, and his men mounted an almost suicidal bayonet attack, fighting to nearly the last man; only three French Legionnaires survived. To this day, the anniversary of 30 April remains the most important day of celebration for Legionnaires.

The French army of General François Achille Bazaine defeated the Mexican army led by General Comonfort in its campaign to relieve the siege of Puebla, at San Lorenzo, to the south of Puebla. Puebla surrendered to the French shortly afterward, on 17 May. On 31 May, President Juárez fled the city with his cabinet, retreating northward to Paso del Norte and later to Chihuahua. Having taken the treasure of the state with them, the government-in-exile remained in Chihuahua until 1867.

French troops under Bazaine entered Mexico City on 7 June 1863. The main army entered the city three days later led by General Forey. General Almonte was appointed the provisional President of Mexico on 16 June, by the Superior Junta (which had been appointed by Forey). The Superior Junta with its 35 members met on 21 June and proclaimed a Catholic Empire on 10 July. The crown was offered to Maximilian, following pressures by Napoleon. Maximilian accepted the crown on 3 October, at the hands of the Comisión Mexicana, sent by the Superior Junta.

Arrival of Maximilian[]

On 28 and 31 March 1864, men from the French man-of-war Cordelière tried to take Mazatlán, but were initially repelled by Mexicans commanded by Colonel .

The French under Bazaine occupied Guadalajara on 6 January 1864, and troops under Douay occupied Zacatecas on 6 February. Further decisive French victories continued with the fall of Acapulco on 3 June, occupation of Durango on 3 July, and the defeat of republicans in the states of Sinaloa and Jalisco in November.

Maximilian formally accepted the crown on 10 April, signing the Treaty of Miramar, and landed at Veracruz on 28 May (or possibly 29 May) 1864 in the SMS Novara. He was enthroned as Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico, with his wife Charlotte of Belgium, known by the Spanish form of her name, Carlota. In reality, Maximilian was a puppet monarch of the Second French Empire.

Maximilian expressed progressive European political ideas, favouring the establishment of a limited monarchy sharing powers with a democratically elected congress. He inspired passage of laws to abolish child labour, limit working hours, and abolish a system of land tenancy that virtually amounted to serfdom among the Indians. This was too liberal to please Mexico's conservatives, and the nation's liberals refused to accept a monarch, leaving Maximilian with few enthusiastic allies within Mexico.

On Sunday, 13 November 1864, three French men-of-war (Victoire, D'Assas and Diamante) shelled Mazatlán 13 times, and Imperial Mexican forces under Manuel Lozada entered and captured the city.

Early Republican victories[]

The French continued with victories in 1865, with Bazaine capturing Oaxaca on 9 February (defeating the city's defenders under General Porfirio Díaz). The French fleet landed soldiers who captured Guaymas on 29 March.

On 11 April, republicans defeated Imperial forces at Tacámbaro in Michoacán. In April and May the republicans had many forces in the states of Sinaloa and Chihuahua. Most towns along the Rio Grande were also occupied by republicans. Throughout the country, the French were now harassed by guerrilla warfare, the kind of fighting that Mexican forces were well used with.

The decree known as the "Black Decree" was issued by Maximilian on 3 October, which threatened any Mexican captured in the war with immediate execution. The decree led to around 11,000 executions. This was later the basis for the next government to order his own execution. Several high-ranking republican officials were executed under this order on 21 October.

France had conquered the heart of Mexico but rebels were still persisting, logistics were being stretched, and the Mexican armies had simply kept fighting to exist.

U.S. diplomacy and involvement[]

As early as 1859, U.S. and Mexican efforts to ratify the McLane-Ocampo Treaty had failed in the bitterly divided U.S. Senate, where tensions were high between the North and the South over slavery issues. Such a treaty would have allowed U.S. construction in Mexico and protection from European forces in exchange for a payment of $4 million to the heavily indebted government of Benito Juárez. On 3 December 1860, President James Buchanan had delivered a speech stating his displeasure at being unable to secure Mexico from European interference:

European governments would have been deprived of all pretext to interfere in the territorial and domestic concerns of Mexico. We should have thus been relieved from the obligation of resisting, even by force, should this become necessary, any attempt of these governments to deprive our neighboring Republic of portions of her territory, a duty from which we could not shrink without abandoning the traditional and established policy of the American people.[20]

United States policy did not change during the French occupation as it had to use its resources for the American Civil War, which lasted 1861 to 1865. President Abraham Lincoln expressed his sympathy to Latin American republics against any European attempt to establish a monarchy. Shortly after the establishment of the Imperial government in April 1864, United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, while maintaining U.S. neutrality, expressed U.S. discomfort at the imposition of a monarchy in Mexico: "Nor can the United States deny that their own safety and destiny to which they aspire are intimately dependent on the continuance of free republican institutions throughout America."[21]

On 4 April 1864, Congress passed a joint resolution:

Resolved, &c., That the Congress of the United States are unwilling, by silence, to leave the nations of the world under the impression that they are indifferent spectators of the deplorable events now transpiring in the Republic of Mexico; and they therefore think fit to declare that it does not accord with the policy of the United States to acknowledge a monarchical government, erected on the ruins of any republican government in America, under the auspices of any European power.[22]

Near the end of the American Civil War, representatives at the 1865 Hampton Roads Conference briefly discussed a proposal for a north–south reconciliation by a joint action against the French in Mexico. In 1865, through the selling of Mexican bonds by Mexican agents in the United States, the Juarez Administration raised between $16-million and $18-million dollars for the purchase of American war material.[23] Between 1865 and 1868, General Herman Sturm acted as an agent to deliver guns and ammunition to the Mexican Republic led by Juarez.[24] In 1866 General Philip Sheridan was in charge of transferring additional supplies and weapons to the Liberal army, including some 30,000 rifles directly from the Baton Rouge Arsenal in Louisiana.[25]

By 1867, Seward shifted American policy from thinly veiled sympathy to the republican government of Juárez to open threat of war to induce a French withdrawal. Seward had invoked the Monroe Doctrine and later stated in 1868, "The Monroe Doctrine, which eight years ago was merely a theory, is now an irreversible fact."[26]

French withdrawal and Republican victories[]

In 1866, choosing Franco-American relations over his Mexican monarchy ambitions, Napoleon III announced the withdrawal of French forces beginning 31 May, abandoning years of hard fought land. The Republicans won a series of crippling victories against Maximilian’s army taking immediate advantage of the end of French military support to the Imperial troops, occupying Chihuahua on 25 March,[27] taking Guadalajara on 8 July,[28] further capturing Matamoros, Tampico and Acapulco in July.[28] Napoleon III urged Maximilian to abandon Mexico and evacuate with the French troops. The French evacuated Monterrey on 26 July,[28] Saltillo on 5 August,[28] and the whole state of Sonora in September.[28] Maximilian's French cabinet members resigned on 18 September.[28] The Republicans defeated imperial troops in the Battle of Miahuatlán in Oaxaca in October, occupying the whole of Oaxaca in November, as well as parts of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato. The combined Austro-Belgian Volunteer Corps was formally disbanded at the end of 1866. Approximately 1,000 of these Austrian and Belgian volunteers chose to enlist in Maximilian's Imperial Army while the remaining 3,428 embarked for Europe.[29] The separate Belgian Legion was also dissolved in December 1866 and 754 returned to their homeland.[30]

On 13 November, Ramón Corona and the French agreed to terms for the withdrawal of the latter forces from Mazatlán. At noon, the French boarded three men-of-war, Rhin, Marie and Talisman and departed Mexico defeated.

Republican triumph, execution of Maximilian[]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2019) |

The Republicans occupied the rest of the states of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato in January. The French evacuated the capital on 5 February.

On 13 February 1867, Maximilian withdrew to Querétaro. The Republicans began a siege of the city on 9 March, and Mexico City on 12 April. An imperial sortie from Querétaro failed on 27 April. Despite hard resistance by the defenders, the siege was bound to end with a Republican victory.

On 11 May, Maximilian resolved to try to escape through the enemy lines. He was intercepted on 15 May. Following a court-martial, he was sentenced to death. Many of the crowned heads of Europe and other prominent figures (including liberals Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi) sent telegrams and letters to Mexico pleading for Maximilian's life to be spared, but Juárez refused to commute the sentence. He believed he had to send a strong message that Mexico would not tolerate any government imposed by foreign powers.

Maximilian was executed on 19 June (along with his generals Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía) on the Cerro de las Campanas, a hill on the outskirts of Querétaro, by the forces loyal to President Benito Juárez, who had kept the federal government functioning during the French intervention. Mexico City surrendered the day after Maximilian was executed.

The republic was restored, and President Juárez was returned to power in the national capital. He made few changes in policy, given that the progressive Maximilian had upheld most of Juárez's liberal reforms.

After the victory, the Conservative party was so thoroughly discredited by its alliance with the invading French troops that it effectively became defunct. The Liberal party was almost unchallenged as a political force during the first years of the "restored republic". In 1871, however, Juárez was re-elected to yet another term as president in spite of a constitutional prohibition of re-elections. The French intervention had ended with the Republican led government being more stable and both internal and external forces were now kept at bay.

Porfirio Díaz (a Liberal general and a hero of the French war, but increasingly conservative in outlook), one of the losing candidates, launched a rebellion against the president. Supported by conservative factions within the Liberal party, the attempted revolt (the so-called Plan de la Noria) was already at the point of defeat when Juárez died in office on 19 July 1872, making it a moot point. Díaz ran against interim president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, lost the election, and retired to his hacienda in Oaxaca. Four years later, in 1876, when Lerdo ran for re-election, Díaz launched a second, successful revolt (the Plan de Tuxtepec) and captured the presidency. He held it through eight terms until 1911 now known as the Porfiriato. After many decades of civil wars, Mexico had finally exhausted itself and the general Porfirio Diaz had forced peace through his regime with no big rebellions or coups occurring.

France's adventure in Mexico had improved relations with Austria through Maximilian but produced no result as France had alienated itself in the international community. During 1866, Prussia went to war with France's indirect ally Austria, which was promptly defeated while French troops were still in Mexico unable to affect the situation in Europe. As for Napoleon's empire, it would later collapse in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian war.

Divisions and disembarkation of allied troops[]

French expeditionary force, 31 December 1862[]

At its peak in 1863, the French expeditionary force counted 38,493 men[7] :740 (which represented 16.25% of the French army).[31] 6,654[8] :231 French died, including 4,830 from disease.[8]:231 Among these losses, 1,918 of the deaths were from the regiment of the French Foreign Legion.[32]:267

Général de Division Forey

1ère Division d'Infanterie (GdD Bazaine)[]

- 1ère Brigade (GdB de Castagny)

- 2e Brigade (GdB ?)

- 20e Bataillon de Chasseurs

- 3ème Régiment de Zouaves

- 95e Régiment d'Infanterie légère

- Bataillon de Tirailleurs algériens

- 2x Marine artillery batteries

2e Division d'Infanterie (GdB Douay – acting)[]

- 1ère Brigade (Col Hellier – acting)

- 1er Bataillon de Chasseurs

- 2e Régiment de Zouaves

- 99e Régiment d'Infanterie légère

- 2e Brigade (GdB Berthier)

- 7e Bataillon de Chasseurs

- 51e Régiment de Ligne

- 62e Régiment de Ligne

- 2x Army artillery batteries

Brigade de Cavallerie (GdB de Mirandol)[]

- 1er Régiment de Marche (2 squadrons each of 1er and 2e Chasseurs d'Afrique)

- 2e Régiment de Marche (2 squadrons each of 3e Chasseurs d'Afrique and 12e Chasseurs)

[]

- Bataillon de Fusiliers-Marins

- 2e Régiment d'Infanterie de Marine

[33]:95–96

Units not yet arrived:

- 7e Régiment de Ligne (2000 men)[34]

- 1e Régiment Étranger (4000 men)[34]

- 2e Bataillon d'Infanterie legère d'Afrique (900 men)[34]

- Bataillon Egyptien

- detachment/ 5e Régiment de Hussards

Belgian Voluntary Troops 1864–65[]

This corps was officially designated as the "Belgian Volunteers", but generally known as the "Belgian Legion".[35]

- Bataillon de l'Impératrice Charlotte (grenadiers)

- Bataillon Roi des Belges (voltigeurs)

16 October 1864[]

- 1st Grenadier Company

- 4 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 125 grenadiers, 6 musicians, 1 canteener

- 2nd Grenadier Company "Bataillon de l'Impératrice"

- 4 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 122 grenadiers, 4 musicians, 1 canteener

- 1st voltigeur Company

- 4 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 122 voltigeurs, 4 musicians, 1 canteener

- 2nd voltigeur Company

- 4 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 121 voltigeurs, 4 musicians, 1 canteener

14 November 1864[]

- 3rd Grenadier Company

- 4 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 68 grenadiers, 6 musicians, 1 canteener

- 4th Grenadier Company

- 4 Officers, 15 Non-commissioned officers, 67 grenadiers, 6 musicians, 1 canteener

- 3rd voltigeur Company

- 3 Officers, 16 Non-commissioned officers, 61 voltigeurs, 3 musicians, 1 canteener

- 4th voltigeur Company

- 3 Officers, 15 Non-commissioned officers, 69 voltigeurs, 4 musicians, 1 canteener

16 December 1864[]

- 5th Grenadier Company

- 6th Grenadier Company

- 5th voltigeur Company

- 6th voltigeur Company

Defense of the Belgian battalion in the Battle of Tacámbaro.

Defense of the Belgian battalion in the Battle of Tacámbaro.- 362 volunteers

27 January 1865[]

- 189 volunteers

15 April 1866[]

- 1st Mounted Company

- 70–80 horsemen (formed from Regiment "Impératrice Charlotte")

16 July 1866[]

- 2nd Mounted Company

- 70–80 horsemen (formed from Regiment "Roi des Belges")

Austrian Voluntary Corps December 1864[]

While officially designated as the Austrian Voluntary Corps, this foreign contingent included Hungarian, Polish and other volunteers from the Danube Monarchy.[37]

- 159 officers

- 403 infantry and jägers (Austrian)

- 366 hussars (Hungarian)

- 16 uhlans (Polish)

- 67 bombardiers (mixed)

- 30 pioneers (mixed)

- several doctors

Egyptian Auxiliary Corps January 1863[]

This unit was commonly designated as the "Egyptian Battalion". It consisted of 453 men (including troops recruited from the Sudan), who were placed under the command of French commandant Mangin of the 3rd Zouave Regiment. Operating effectively in the Veracruz region, the Corps suffered 126 casualties until being withdrawn to Egypt in May 1867.[38] Maximilian protested the loss of the Egyptian Corps, ostensibly to suppress a rebellion in the Sudan, because they were "extremely helpful in the hot lands".[39]

- A battalion commander

- A captain

- A lieutenant

- 8 sergeants

- 15 corporals

- 359 soldiers

- 39 recruits

Spanish Expeditionary Force January 1862[]

- 5373 infantry (two brigades)

- 26 pieces of artillery,

- 490 bombardiers

- 208 engineers

- 100 administrators

- 173 cavalry

[8]:103

Captain Yarka, Romanian volunteer (1863)[]

At least one Romanian, an officer, served with the French forces. Captain Yarka of the Romanian Army served with the 3rd Regiment of Chasseurs d'Afrique as a volunteer, keeping the same rank. In April 1863, Yarka engaged a Republican ("Juariste") Colonel in one-on-one combat, killing him. Yarka himself was wounded. In contemporary French sources, he is referred to as Wallachian ("Valaque").[40][41]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert Ryal Miller (1961). "The American Legion of Honor in Mexico". Pacific Historical Review. Berkeley, California, United States: University of California Press. 30 (3): 229–241. doi:10.2307/3636920. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3636920.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Péter Torbágyi (2008). Magyar kivándorlás Latin-Amerikába az első világháború előtt (PDF) (in Hungarian). Szeged, Hungary: University of Szeged. p. 42. ISBN 978-963-482-937-9. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Richard Leroy Hill (1995). A Black corps d'élite: an Egyptian Sudanese conscript battalion with the French Army in Mexico, 1863-1867, and its survivors in subsequent African history. East Lansing, United States: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9780870133398.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Walter Klinger (2008). Für Kaiser Max nach Mexiko- Das Österreichische Freiwilligenkorps in Mexiko 1864/67 (in German). Munich, Germany: Grin Verlag. ISBN 978-3640141920. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Louis Noir, Achille Faure, 1867, Campagne du Mexique: Mexico (souvenirs d'un zouave), p. 135

- ^ Le moniteur de l'armée: 1863

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gustave Niox (1874). Expédition du Mexique, 1861-1867; récit politique & militaire (in French). Paris, France: J. Dumaine. ASIN B004IL4IB4. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jean-Charles Chenu (1877). "Expédition du Mexique" [Mexican expedition]. Aperçu sur les expéditions de Chine, Cochinchine, Syrie et Mexique : Suivi d'une étude sur la fièvre jaune par le Dr Fuzier [Overview of the expeditions in China, Cochinchina, Syria and Mexico: A Follow-up study on the yellow fever by Dr. Fuzier] (in French). Paris, France: Masson. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Martín de las Torres (1867). El Archiduque Maximiliano de Austria en Méjico (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain: Luis Tasso. ISBN 9781271445400. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Louis Noir, Achille Faure, 1867, Campagne du Mexique: Mexico (souvenirs d'un zouave), p. 135

- ^ Le moniteur de l'armée: 1863

- ^ Jump up to: a b Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. p. 305.

- ^ René Chartrand (1994). Lee Johnson (ed.). The Mexican Adventure 1861–67. Men-at-arms. 272. Illustrated by Richard Hook. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 185532430X.

- ^ Richard Leslie Hill; Peter C. Hogg (1995). A Black corps d'élite: an Egyptian Sudanese conscript battalion with the French Army in Mexico, 1863–1867, and its survivors in subsequent African history. East Lansing, United States: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9780870133398.

- ^ known as Expédition du Mexique in France at the time and today as Intervention française au Mexique

- ^ "Mexico and the West Indies" (pdf). Daily Alta California. San Francisco, United States: Robert B. Semple. XVI. (5310): 1. 16 September 1864. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kohn, George Childs, ed. (2007). Dictionary of Wars (3rd ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7. OCLC 466183689.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Henry Jarvis Raymond (12 July 1867). "The history of foreign intervention in Mexico II" (pdf). The New York Times: 1. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. p. 4. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ Manning, William R.; James Morton Callahan; John H. Latané; Philip Brown; James L. Slayden; Joseph Wheless; James Brown Scott (25 April 1914). "Statements, Interpretations, and Applications of the Monroe Doctrine and of More or Less Allied Doctrines". American Society of International Law. 8: 90. JSTOR 25656497.

- ^ Manning, William R.; James Morton Callahan; John H. Latané; Philip Brown; James L. Slayden; Joseph Wheless; James Brown Scott (25 April 1914). "Statements, Interpretations, and Applications of the Monroe Doctrine and of More or Less Allied Doctrines". American Society of International Law. 8: 101. JSTOR 25656497.

- ^ McPherson, Edward (1864). The Political History of the United States of America During the Great Rebellion: From November 6, 1860, to July 4, 1864; Including a Classified Summary of the Legislation of the Second Session of the Thirty-sixth Congress, the Three Sessions of the Thirty-seventh Congress, the First Session of the Thirty-eighth Congress, with the Votes Thereon, and the Important Executive, Judicial, and Politico-military Facts of that Eventful Period; Together with the Organization, Legislation, and General Proceedings of the Rebel Administration. Philip & Solomons. p. 349.

- ^ Hart, John Mason (2002). Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico Since the Civil War. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-520-90077-4.

- ^ Robert H. Buck, Captain, Recorder. Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States Commandery of the state of Colorado, Denver. 10 April 1907. Indiana State Library.

- ^ Hart, James Mason (2002). Empire and Revolution: The American in Mexico Since the Civil War. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-520-90077-4.

- ^ Manning, William R.; Callahan, James Morton; Latané, John H.; Brown, Philip; Slayden, James L.; Wheless, Joseph; Scott, James Brown (25 April 1914). "Statements, Interpretations, and Applications of the Monroe Doctrine and of More or Less Allied Doctrines". American Society of International Law. 8: 105. JSTOR 25656497.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. p. 4. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. p. 5. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ Rene Chartrand, page 36 "The Mexican Adventure 1861-67", ISBN 1-85532-430-X

- ^ Rene Chartrand, page 37 "The Mexican Adventure 1861-67", ISBN 1-85532-430-X

- ^ Raymond, Henry Jarvis, ed. (10 July 1862). "The military force of France.; The Actual Organization of the Army Its Strength and Effectiveness. The Imperial Guard, the Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, Administration, Gen D'Armerie. General Staff of the army. The Military Schools, the invalids, the government of the army, Annual cost of the French Army". The New York Times. New York, United States: The Times. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Pénette, Marcel; Castaingt, Jean (1962). La Legión Extranjera en la Intervención Francesa [The Foreign Legion in the French Intervention] (PDF) (in Spanish). Ciudad de México, Mexico: Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Falcke Martin, Percy (1914). Maximilian in Mexico. The story of the French intervention (1861–1867). New York, United States: C. Scribner's sons. ISBN 9781445576466. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Mexican expedition" (pdf). Lyttelton Times. Thorndon, New Zealand: Papers Past. XIX. (1090): 9. 22 April 1863. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. pp. 35–36. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ Fren Funcken; Lilian Funcken (1981). Burgess, Donald (ed.). "The Forgotten Legion" (PDF). Campaigns Magazine – International Magazine of Military Miniatures. Los Angeles, United States: Marengo Publications. 6 (32): 31–34. ISBN 9780803919235. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. p. 37. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861-67. p. 37. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota. Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Louis Noir, Achille Faure, 1867, Campagne du Mexique: Mexico (souvenirs d'un zouave), p. 135

- ^ Le moniteur de l'armée: 1863

Further reading[]

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico: being a popular history of the Mexican people from the Earliest Civilization to the Present Time The Bancroft Company, New York, 1914, pp. 466–506

- Brittsan, Zachary. Popular Politics and Rebellion in Mexico: Manuel Lozada and La Reforma, 1855-1876. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press 2015.

- Corti, Egon Caesar. Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico (2 vol 1968). 976 pages

- Cunningham, Michele. Mexico and the Foreign Policy of Napoleon III, Palgrave Macmillan, 2001

- Garay, Lerma. Antonio. Mazatlán Decimonónico, Autoedición. 2005. ISBN 1-59872-220-4.

- Sheridan, Philip H. Personal Memoirs of P.H. Sheridan[permanent dead link], Charles L. Webster & Co., 1888, ISBN 1-58218-185-3 (vol. 2, part 5, Chapter IX)

- Topik, Steven C. "When Mexico Had the Blues: A Transatlantic Tale of Bonds, Bankers, and Nationalists, 1862–1910," American Historical Review, June 2000, Vol. 105 Issue 3, pp 714–40

External links[]

- Second French intervention in Mexico

- 1860s in Mexico

- 19th-century colonization of the Americas

- 19th century in Mexico

- 19th-century guerrilla wars

- 1861 in the French colonial empire

- 1862 in the French colonial empire

- 1863 in the French colonial empire

- 1864 in the French colonial empire

- 1865 in the French colonial empire

- 1866 in the French colonial empire

- 1867 in the French colonial empire

- 1861 in Mexico

- 1862 in Mexico

- 1863 in Mexico

- 1864 in Mexico

- 1865 in Mexico

- 1866 in Mexico

- 1867 in Mexico

- Conflicts in 1861

- Conflicts in 1862

- Conflicts in 1863

- Conflicts in 1864

- Conflicts in 1865

- Conflicts in 1866

- Conflicts in 1867

- Expeditions from France

- French colonization of the Americas

- Foreign intervention

- Foreign relations during the American Civil War

- History of Mexico

- Independent Mexico

- Invasions by France

- Invasions of Mexico

- Maximilian I of Mexico

- Napoleon III

- Proxy wars

- Second French Empire

- Wars involving Austria

- Wars involving Belgium

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving Mexico

- Wars involving Spain

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- Wars involving the United States

- France–Mexico relations