Minix

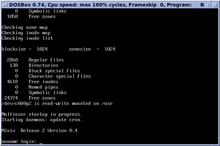

The MINIX 3.3.0 login prompt | |

| Developer | Andrew S. Tanenbaum et al. |

|---|---|

| Written in | C |

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open-source |

| Initial release | 1987 |

| Latest release | 3.3.0[1] / 16 September 2014 |

| Latest preview | 3.4.0rc6[2] / 9 May 2017 |

| Repository | |

| Marketing target | Teaching (v1, v2) Embedded systems (v3) |

| Available in | English |

| Platforms | PC compatibles, PC, PC/AT, PS/2, Motorola 68000, SPARC, Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, Macintosh, SPARCstation, Intel 386, NS32532, ARM, Inmos transputer, Intel Management Engine[3] |

| Kernel type | Microkernel |

| License | 2005: BSD-3-Clause[a][4] 2000: BSD-3-Clause[5][6] 1995: Proprietary[7] 1987: Proprietary[8] |

| Official website | www |

Minix (from "mini-Unix") is a POSIX-compliant (since version 2.0),[9][10] Unix-like operating system based on a microkernel architecture.

Early versions of MINIX were created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum for educational purposes. Starting with MINIX 3, the primary aim of development shifted from education to the creation of a highly reliable and self-healing microkernel OS. MINIX is now developed as open-source software.

MINIX was first released in 1987, with its complete source code made available to universities for study in courses and research. It has been free and open-source software since it was re-licensed under the BSD-3-Clause license in April 2000.[5]

Implementation[]

Minix 1.0[]

Andrew S. Tanenbaum created MINIX at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam to exemplify the principles conveyed in his textbook, Operating Systems: Design and Implementation (1987).

An abridged 12,000 lines of the C source code of the kernel, memory manager, and file system of MINIX 1.0 are printed in the book. Prentice-Hall also released MINIX source code and binaries on floppy disk with a reference manual. MINIX 1 was system-call compatible with Seventh Edition Unix.[11]

Tanenbaum originally developed MINIX for compatibility with the IBM PC and IBM PC/AT 8088 microcomputers available at the time.

Minix 1.5[]

MINIX 1.5, released in 1991, included support for MicroChannel IBM PS/2 systems and was also ported to the Motorola 68000 and SPARC architectures, supporting the Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, Apple Macintosh[12] and Sun SPARCstation computer platforms. There were also unofficial ports to Intel 386 PC compatibles (in 32-bit protected mode), National Semiconductor NS32532, ARM and Inmos transputer processors. Meiko Scientific used an early version of MINIX as the basis for the MeikOS operating system for its transputer-based Computing Surface parallel computers. A version of MINIX running as a user process under SunOS and Solaris was also available, a simulator named SMX (operating system) or just SMX for short.[13][14]

Minix 2.0[]

Demand for the 68k-based architectures waned, however, and MINIX 2.0, released in 1997, was only available for the x86 and Solaris-hosted SPARC architectures. It was the subject of the second edition of Tanenbaum's textbook, cowritten with Albert Woodhull and was distributed on a CD-ROM included with the book. MINIX 2.0 added POSIX.1 compliance, support for 386 and later processors in 32-bit mode and replaced the Amoeba network protocols included in MINIX 1.5 with a TCP/IP stack.

Version 2.0.3 was released in May 2001. It was the first version after MINIX had been relicensed under the BSD-3-Clause license, which was retroactively applied to all previous versions.[15]

Minix-vmd[]

Minix-vmd is a variant of MINIX 2.0 for Intel IA-32-compatible processors, created by two Vrije Universiteit researchers, which adds virtual memory and support for the X Window System.

Minix 3[]

Minix 3 was publicly announced on 24 October 2005 by Tanenbaum during his keynote speech at the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP). Although it still serves as an example for the new edition of Tanenbaum's textbook -coauthored by Albert S. Woodhull-, it is comprehensively redesigned to be "usable as a serious system on resource-limited and embedded computers and for applications requiring high reliability."[16]

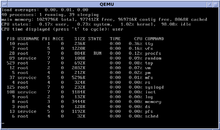

Minix 3 currently supports IA-32 and ARM architecture systems. It is available in a Live CD format that allows it to be used on a computer without installing it on the hard drive, and in versions compatible with hardware emulating and virtualizing systems, including Bochs, QEMU, VMware Workstation/Fusion, VirtualBox, and Microsoft Virtual PC.

Version 3.1.2 was released on 18 April 2006. It was the first version after MINIX had been relicensed under the BSD-3-Clause license with a new fourth clause.[17]

Version 3.1.5 was released on 5 November 2009. It contains X11, emacs, vi, cc, gcc, perl, python, ash, bash, zsh, ftp, ssh, telnet, pine, and over 400 other common Unix utility programs. With the addition of X11, this version marks the transition away from a text-only system. In many cases it can automatically restart a crashed driver without affecting running processes. In this way, MINIX is self-healing and can be used in applications demanding high reliability. MINIX 3 also has support for virtual memory management, making it suitable for desktop OS use.[18] Desktop applications such as Firefox and OpenOffice.org are not yet available for MINIX 3 however.

As of version 3.2.0, the userland was mostly replaced by that of NetBSD and support from pkgsrc became possible, increasing the available software applications that MINIX can use. Clang replaced the prior compiler (with GCC now having to be manually compiled), and GDB, the GNU debugger, was ported.[19][20]

Minix 3.3.0, released in September 2014, brought ARM support.

Minix 3.4.0RC, Release Candidates became available in January 2016;[21] however, a stable release of MINIX 3.4.0 is yet to be announced.

Minix supports many programming languages, including C, C++, FORTRAN, Modula-2, Pascal, Perl, Python, and Tcl.

Minix 3 still has an active development community with over 50 people attending MINIXCon 2016, a conference to discuss the history and future of MINIX.[22]

All Intel chipsets post-2015 are running MINIX 3 internally as the software component of the Intel Management Engine.[23][24]

Relationship with Linux[]

Early influence[]

Linus Torvalds used and appreciated Minix,[25] but his design deviated from the Minix architecture in significant ways, most notably by employing a monolithic kernel instead of a microkernel. This was disapproved of by Tanenbaum in the Tanenbaum–Torvalds debate. Tanenbaum explained again his rationale for using a microkernel in May 2006.[26]

Early Linux kernel development was done on a Minix host system, which led to Linux inheriting various features from Minix, such as the Minix file system.

Samizdat claims[]

In May 2004, Kenneth Brown of the Alexis de Tocqueville Institution made the accusation that major parts of the Linux kernel had been copied from the MINIX codebase, in a book named Samizdat.[27] These accusations were rebutted universally—most prominently by Tanenbaum, who strongly criticised Brown and published a long rebuttal on his own personal Web site, also claiming that Brown was funded by Microsoft.[9][10]

Licensing[]

At the time of MINIX's original development, its license was relatively liberal. Its licensing fee was very small ($69) relative to those of other operating systems. Tanenbaum wished for MINIX to be as accessible as possible to students, but his publisher was unwilling to offer material (such as the source code) that could be copied freely, so a restrictive license requiring a nominal fee (included in the price of Tanenbaum's book) was applied as a compromise. This prevented the use of MINIX as the basis for a freely distributed software system.

When free and open-source Unix-like operating systems such as Linux and 386BSD became available in the early 1990s, many volunteer software developers abandoned MINIX in favor of these. In April 2000, MINIX became free and open-source software under the BSD-3-Clause license, which was retroactively applied to all previous versions.[15][6] However, by this time other operating systems had surpassed its capabilities, and it remained primarily an operating system for students and hobbyists. In late 2005, MINIX was relicensed with a fourth clause added to the BSD-3-Clause license.[4]

See also[]

- MINIX file system

- Minix-vmd

- MINIX 3

- Redox —an operating system in Rust using a Minix-like kernel

- Xinu

Notes[]

- ^ BSD-3-Clause with a fourth clause.

References[]

- ^ Michael Larabel (2014-09-16). "Minix 3.3 Released With Cortex-A8 ARM Support, NetBSD Userland Compatibility". Phoronix.

- ^ MINIX 3.4 RC6 Released - Phoronix

- ^ "Intel ME: The Way of Static Analysis". Retrieved 2017-07-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Minix license". Archived from the original on 2005-11-24. Retrieved 2005-11-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MINIX is now available under the BSD license". Archived from the original on 2006-05-08. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Minix". Archived from the original on 2006-10-13. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

The Minix license changed in April 2000, and applies retroactively to all previous Minix distributions, even though they still carry the old, more restrictive license within.

- ^ "LICENSE (1.7.0 to 2.0.2)". Archived from the original on 1997-07-26. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ "Minix versions and their use in teaching". Archived from the original on 2006-07-11. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanenbaum, Andrew S (20 May 2004). "Some Notes on the "Who wrote Linux" Kerfuffle, Release 1.5". Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Woodhull, Albert S.; Sambuc, Lionel (March 11, 2015). "MINIX 3 FAQ". Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Woodhull, Albert S. (1997) [1986]. Operating Systems Design and Implementation (Second ed.). ISBN 0-13-638677-6. OCLC 35792209. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "MacMinix".

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Woodhull, Albert S.; Bot, Kees (July 22, 2005). "Welcome to MINIX" (TXT). Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ Flouris, M. "Installing and running MINIX for Solaris (SMX)". Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BSD-3-Clause". Archived from the original on 2000-04-14. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ Herder, J. N.; Bos, H.; Gras, B.; Homburg, P.; Tanenbaum, A. S. (2006). "Minix 3". ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review. 40 (3): 80. doi:10.1145/1151374.1151391. S2CID 30216714.

- ^ "LICENSE". Archived from the original on 2021-06-15. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ Schmidt, Ulrich (November 10, 2010). "New to minix". Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "MINIX Releases". wiki.minix3.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ MINIX 3.2: A microkernel with NetBSD applications [LWN.net]

- ^ "Index of /iso/snapshot/". download.minix3.org. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- ^ "MINIXCon 2016". www.minix3.org. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- ^ "Positive Technologies research". blog.ptsecurity.com. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ Minix: Intel's hidden in-chip operating system

- ^ Moody, Glyn (2015-08-25). "How Linux was born, as told by Linus Torvalds himself". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (May 12, 2006). "Tanenbaum-Torvalds Debate: Part II". Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ Brown, Kenneth (June 4, 2004). "Samizdat's critics… Brown replies". Alexis de Tocqueville Institution. Archived from the original on October 22, 2004. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

External links[]

- MINIX

- 1987 software

- ARM operating systems

- Computer science in the Netherlands

- Dutch inventions

- Educational operating systems

- Free software operating systems

- Information technology in the Netherlands

- Lightweight Unix-like systems

- Microkernel-based operating systems

- Microkernels

- Operating system distributions bootable from read-only media

- Software using the BSD license

- Unix variants