Monotonic function

In mathematics, a monotonic function (or monotone function) is a function between ordered sets that preserves or reverses the given order.[1][2][3] This concept first arose in calculus, and was later generalized to the more abstract setting of order theory.

In calculus and analysis[]

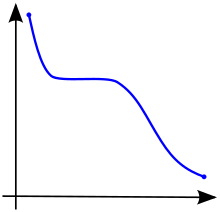

In calculus, a function defined on a subset of the real numbers with real values is called monotonic if and only if it is either entirely non-increasing, or entirely non-decreasing.[2] That is, as per Fig. 1, a function that increases monotonically does not exclusively have to increase, it simply must not decrease.

A function is called monotonically increasing (also increasing or non-decreasing),[3] if for all and such that one has , so preserves the order (see Figure 1). Likewise, a function is called monotonically decreasing (also decreasing or non-increasing)[3] if, whenever , then , so it reverses the order (see Figure 2).

If the order in the definition of monotonicity is replaced by the strict order , then one obtains a stronger requirement. A function with this property is called strictly increasing (also increasing).[3][4] Again, by inverting the order symbol, one finds a corresponding concept called strictly decreasing (also decreasing).[3][4] A function may be called strictly monotone if it is either strictly increasing or strictly decreasing. Functions that are strictly monotone are one-to-one (because for not equal to , either or and so, by monotonicity, either or , thus .)

If it is not clear that "increasing" and "decreasing" are taken to include the possibility of repeating the same value at successive arguments, one may use the terms weakly monotone, weakly increasing and weakly decreasing to stress this possibility.

The terms "non-decreasing" and "non-increasing" should not be confused with the (much weaker) negative qualifications "not decreasing" and "not increasing". For example, the function of figure 3 first falls, then rises, then falls again. It is therefore not decreasing and not increasing, but it is neither non-decreasing nor non-increasing.

A function is said to be absolutely monotonic over an interval if the derivatives of all orders of are nonnegative or all nonpositive at all points on the interval.

Inverse of function[]

A function that is monotonic, but not strictly monotonic, and thus constant on an interval, doesn't have an inverse. This is because in order for a function to have an inverse, there needs to be a one-to-one mapping from the range to the domain of the function. Since a monotonic function has some values that are constant in its domain, this means that there would be more than one value in the range that maps to this constant value.

However, a function y = g(x) that is strictly monotonic, has an inverse function such that x = h(y) because there is guaranteed to always be a one-to-one mapping from range to domain of the function. Also, a function can be said to be strictly monotonic on a range of values, and thus have an inverse on that range of value. For example, if y = g(x) is strictly monotonic on the range [a, b], then it has an inverse x = h(y) on the range [g(a), g(b)], but we cannot say the entire range of the function has an inverse.

Note, some textbooks[which?] mistakenly state that an inverse exists for a monotonic function, when they really mean that an inverse exists for a strictly monotonic function.

Monotonic transformation[]

The term monotonic transformation (or monotone transformation) can also possibly cause some confusion because it refers to a transformation by a strictly increasing function. This is the case in economics with respect to the ordinal properties of a utility function being preserved across a monotonic transform (see also monotone preferences).[5] In this context, what we are calling a "monotonic transformation" is, more accurately, called a "positive monotonic transformation", in order to distinguish it from a “negative monotonic transformation,” which reverses the order of the numbers.[6]

Some basic applications and results[]

The following properties are true for a monotonic function :

- has limits from the right and from the left at every point of its domain;

- has a limit at positive or negative infinity () of either a real number, , or .

- can only have jump discontinuities;

- can only have countably many discontinuities in its domain. The discontinuities, however, do not necessarily consist of isolated points and may even be dense in an interval (a, b). For example, for any summable sequence of positive numbers and any enumeration of the rational numbers, the monotonically increasing function is continuous exactly at every irrational number (cf. picture). It is the cumulative distribution function of the discrete measure on the rational numbers, where is the weight of .

These properties are the reason why monotonic functions are useful in technical work in analysis. Some more facts about these functions are:

- if is a monotonic function defined on an interval , then is differentiable almost everywhere on ; i.e. the set of numbers in such that is not differentiable in has Lebesgue measure zero. In addition, this result cannot be improved to countable: see Cantor function.

- if this set is countable, then is absolutely continuous.

- if is a monotonic function defined on an interval , then is Riemann integrable.

An important application of monotonic functions is in probability theory. If is a random variable, its cumulative distribution function is a monotonically increasing function.

A function is unimodal if it is monotonically increasing up to some point (the mode) and then monotonically decreasing.

When is a strictly monotonic function, then is injective on its domain, and if is the range of , then there is an inverse function on for . In contrast, each constant function is monotonic, but not injective,[7] and hence cannot have an inverse.

In topology[]

A map is said to be monotone if each of its fibers is connected; i.e. for each element in the (possibly empty) set is connected.

In functional analysis[]

In functional analysis on a topological vector space , a (possibly non-linear) operator is said to be a monotone operator if

Kachurovskii's theorem shows that convex functions on Banach spaces have monotonic operators as their derivatives.

A subset of is said to be a monotone set if for every pair and in ,

is said to be maximal monotone if it is maximal among all monotone sets in the sense of set inclusion. The graph of a monotone operator is a monotone set. A monotone operator is said to be maximal monotone if its graph is a maximal monotone set.

In order theory[]

Order theory deals with arbitrary partially ordered sets and preordered sets as a generalization of real numbers. The above definition of monotonicity is relevant in these cases as well. However, the terms "increasing" and "decreasing" are avoided, since their conventional pictorial representation does not apply to orders that are not total. Furthermore, the strict relations < and > are of little use in many non-total orders and hence no additional terminology is introduced for them.

Letting ≤ denote the partial order relation of any partially ordered set, a monotone function, also called isotone, or order-preserving, satisfies the property

- x ≤ y implies f(x) ≤ f(y),

for all x and y in its domain. The composite of two monotone mappings is also monotone.

The dual notion is often called antitone, anti-monotone, or order-reversing. Hence, an antitone function f satisfies the property

- x ≤ y implies f(y) ≤ f(x),

for all x and y in its domain.

A constant function is both monotone and antitone; conversely, if f is both monotone and antitone, and if the domain of f is a lattice, then f must be constant.

Monotone functions are central in order theory. They appear in most articles on the subject and examples from special applications are found in these places. Some notable special monotone functions are order embeddings (functions for which x ≤ y if and only if f(x) ≤ f(y)) and order isomorphisms (surjective order embeddings).

In the context of search algorithms[]

In the context of search algorithms monotonicity (also called consistency) is a condition applied to heuristic functions. A heuristic h(n) is monotonic if, for every node n and every successor n' of n generated by any action a, the estimated cost of reaching the goal from n is no greater than the step cost of getting to n' plus the estimated cost of reaching the goal from n' ,

This is a form of triangle inequality, with n, n', and the goal Gn closest to n. Because every monotonic heuristic is also admissible, monotonicity is a stricter requirement than admissibility. Some heuristic algorithms such as A* can be proven optimal provided that the heuristic they use is monotonic.[8]

In Boolean functions[]

With the nonmonotonic function "if a then both b and c", false nodes appear above true nodes. |

Hasse diagram of the monotonic function "at least two of a, b, c hold". Colors indicate function output values. |

In Boolean algebra, a monotonic function is one such that for all ai and bi in {0,1}, if a1 ≤ b1, a2 ≤ b2, ..., an ≤ bn (i.e. the Cartesian product {0, 1}n is ordered coordinatewise), then f(a1, ..., an) ≤ f(b1, ..., bn). In other words, a Boolean function is monotonic if, for every combination of inputs, switching one of the inputs from false to true can only cause the output to switch from false to true and not from true to false. Graphically, this means that an n-ary Boolean function is monotonic when its representation as an n-cube labelled with truth values has no upward edge from true to false. (This labelled Hasse diagram is the dual of the function's labelled Venn diagram, which is the more common representation for n ≤ 3.)

The monotonic Boolean functions are precisely those that can be defined by an expression combining the inputs (which may appear more than once) using only the operators and and or (in particular not is forbidden). For instance "at least two of a, b, c hold" is a monotonic function of a, b, c, since it can be written for instance as ((a and b) or (a and c) or (b and c)).

The number of such functions on n variables is known as the Dedekind number of n.

See also[]

- Monotone cubic interpolation

- Pseudo-monotone operator

- Spearman's rank correlation coefficient - measure of monotonicity in a set of data

- Total monotonicity

- Cyclical monotonicity

- Operator monotone function

Notes[]

- ^ Clapham, Christopher; Nicholson, James (2014). Oxford Concise Dictionary of Mathematics (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Stover, Christopher. "Monotonic Function". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ^ a b c d e "Monotone function". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ^ a b Spivak, Michael (1994). Calculus. 1572 West Gray, #377 Houston, Texas 77019: Publish or Perish, Inc. p. 192. ISBN 0-914098-89-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ See the section on Cardinal Versus Ordinal Utility in Simon & Blume (1994).

- ^ Varian, Hal R. (2010). Intermediate Microeconomics (8th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 56. ISBN 9780393934243.

- ^ if its domain has more than one element

- ^ Conditions for optimality: Admissibility and consistency pg. 94-95 (Russell & Norvig 2010).

Bibliography[]

- Bartle, Robert G. (1976). The elements of real analysis (second ed.).

- Grätzer, George (1971). Lattice theory: first concepts and distributive lattices. ISBN 0-7167-0442-0.

- Pemberton, Malcolm; Rau, Nicholas (2001). Mathematics for economists: an introductory textbook. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3341-1.

- Renardy, Michael & Rogers, Robert C. (2004). An introduction to partial differential equations. Texts in Applied Mathematics 13 (Second ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 356. ISBN 0-387-00444-0.

- Riesz, Frigyes & Béla Szőkefalvi-Nagy (1990). Functional Analysis. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-66289-3.

- Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2010). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-604259-4.

- Simon, Carl P.; Blume, Lawrence (April 1994). Mathematics for Economists (first ed.). ISBN 978-0-393-95733-4. (Definition 9.31)

External links[]

- "Monotone function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Convergence of a Monotonic Sequence by Anik Debnath and Thomas Roxlo (The Harker School), Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Monotonic Function". MathWorld.

- Functional analysis

- Order theory

- Real analysis

- Types of functions

![\left[a, b\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f30926fb280a9fdf66fd931e14d4363cb824feaa)

![{\displaystyle [u_{1},w_{1}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/42f2c67bc4887974d491ba4a419dc798ed50d8cd)

![{\displaystyle [u_{2},w_{2}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32202d66739c2039a8b74e861330c713a44db704)