Mormon art

Mormon art comprises all visual art created to depict the principles and teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), as well as art deriving from the inspiration of an artist's LDS religious views. Mormon art includes painting, sculpture, quilt work, photography, graphic art, and other mediums, and shares common attributes reflecting Latter-day Saint teachings and values.

Mormon themes and aesthetic[]

Themes[]

Numerous thematic components may be found in Mormon art. These range from being only inclusive of the Mormon faith to the simple underlying theme of spirituality that a Mormon artist attempts to render in a landscape or more general subject matter.

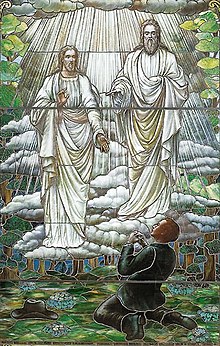

Most Mormon art is both Christian-themed and specific to the Mormon faith. It includes biblical depictions from the Old Testament and the life of Jesus Christ in the New Testament, as well as Book of Mormon scenes and the history of the LDS Church. Many of these LDS historical accounts depicted in art include, what Mormons believe to be, the restoration of the Gospel of Jesus in the mid-19th century, scenes from the life of Joseph Smith, Jr. such as his First Vision and his death, and the migration of the Mormon pioneers from Nauvoo, Illinois to Utah. LDS gospel principles, values, and the teachings of the church are also important art themes, especially to the latter half of the 20th century. These are often represented literally or allegorically as in landscape paintings representing spirituality, personal inspiration, God's love, and the wonders of God.

Although the most common themes in Mormon art are historical and principle-based, specific to the LDS faith, the decade following the founding of the church on April 6, 1830, and continuing on through the end of second half of the 19th century, revealed little of these themes. Most artists who converted to the Mormon faith came from England and primarily exercised their talents by depicting the surrounding landscapes of the Mormon pioneer migration route. Their British art education concentrated on the traditional English Romantic style and theme rather than genre and historical themes.[1] These themes are a rarity during the initial growth of the church. One of the few exceptions that strays from this category of Romantic art is a painting by William Armitage (1817–1890) of London. The painting depicts LDS founder Joseph Smith preaching to the Native Americans, and was commissioned by the church for the Salt Lake Temple.

One British artist associated with the English Romantic tradition was Frederick Piercy (1830–1891), who converted to the church in 1853. His contribution to Mormon art history is his sketches and paintings of the western landscape as he migrated to Utah. He compiled these renderings into an LDS emigrant record of the Mormon route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts holds a number of his original works.

It was not until the late 1850s and after, particularly in the beginning of World War One, when Mormon artists began to depict historical and genre-based paintings to celebrate their faith in the church.

One of the first artists to begin this historical trend in Mormon art was Scandinavian-born artist C. C. A. Christensen (1831–1912). He had trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and used his talents to create one of his most famous series of paintings, Mormon Panorama, made up of 23 paintings depicting the church's history.

Other artists that followed Christesen's thematic choice were Minerva Teichert, LeConte Stewart, and Arnold Friberg. Of these, Friberg is known for depictions of Book of Mormon stories and history of the United States. One of his most recognizable paintings is The Prayer at Valley Forge, featuring George Washington kneeling at Valley Forge, completed in 1975.

Due to the religion's rapid membership growth in the 20th century, Mormon art created during this period reflects the diverse cultural styles within the church and range from depicting the historical to the personal interpretation of the historical, and also contain a spiritual and faithful basis.

The LDS Church places great importance on the power and use of art.[2] Mormon art is circulated primarily within the church community via monthly magazines published by the church and church posters used for teaching Sunday School classes, Home and Visiting, and missionary work. The magazines that are distributed monthly to members with a subscription are the Ensign, the Liahona, the New Era, and The Friend. The purpose of Mormon art creation and circulation is to provide inspiration and encouragement to LDS members, and to instruct and remind them of the teaching and values of the church.[3]

A popular method of reaching out to the youth is through "Mormonads" (posters with social or religious messages), which are available through the New Era (the LDS Church's youth magazine), the church's website, and independent church bookstores. Mormonads are available in poster-size and index-card sizes.[4]

Aesthetic diversity and commonality[]

Mormon art does not claim a particular style or aesthetic. Considered a young religion, Mormonism is not quite 200 years old and has primarily expanded in the 20th century, when artistic and cultural freedom concurrently increased. Today, there are more members of the LDS church outside of the United States than within. Accordingly, Mormon art varies widely in style.

Richard G. Oman, expert on LDS art and curator of acquisitions for the LDS Church History Museum prior to 2010, states in an excerpt on visual artists in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism that the church purposefully holds no limitations on LDS artistic style to promote stylistic diversity:

"The absence of an official liturgical art has kept the Church from directing its artists into specified stylistic traditions. This has been especially conducive to variety in art as the Church has expanded into many different cultures, with differing artistic styles and traditions."[1]

The LDS church recognizes the diverse demography and cultural differences within the church. Oman says that the church consequently embraces and promotes the various artistic attributes to "broaden [perspectives] so the Saints all over the world would be celebrated."[5]

One way the church showed their support for worldwide Mormon art was by establishing and hosting the International Art Competition in 1987.[6] The Church History Museum advertises that:

"Latter-day Saint artists are citizens of many lands and come from many walks of life—and their diverse experiences are reflected in their art, for art is an important part of Latter-day Saint life and communication. The Church History Museum continues to encourage artists worldwide to express their faith through their native traditions."[7]

The juried competition and exhibition is held every three years, inviting LDS artists worldwide to create and submit works of art related to a gospel theme dedicated to the year in which it is held. A number of art pieces are then exhibited at the Church History Museum. The most recent was the Ninth International Art Competition, running from March 16, 2012 – October 14, 2012. The theme was "Make Known His Wonderful Works." More than 1,150 artists entered, and the museum displayed 198 works. Prizes were awarded to 20, and 15 artworks have been purchased by the museum, adding to the church's already vast collection of artwork.[8]

The collection, dispersed throughout temples of the world and also held in the Church History Museum, includes a collection of Rembrandt etchings. In 2005, the museum exhibited 48 of Rembrandt's 70 biblical etchings. The museum had acquired 17, with the remaining having been loaned by the Museum of Art at Brigham Young University and by a private collector. The biblical-themed exhibit, Rembrandt: The Biblical Etchings,[9] included Old Testament stories such as that of Abraham, and scenes from the life of Jesus Christ in the New Testament. The collection was exhibited from May 14, 2005, through December 14, 2005, and online for a short period after the museum exhibition. Some etchings acquired for the collection were Self-Portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill, 1639; Christ and the Woman of Samaria, 1658; and Christ Ministering, about 1640–49.[10]

Despite this variety of styles produced by LDS artists from around the globe, all LDS art is interrelated by means of a shared religious belief. Oman also wrote of aesthetic uniformity:

"While the work of LDS artists encompasses many historical and cultural styles, its unity derives from their shared religious beliefs and from recurring LDS religious themes in their works ... Some of the aesthetic constants of LDS artists are the narrative tradition in painting, a reverence for nature, absence of nihilism, support of traditional societal values, respect for the human body, a strong sense of aesthetic structure, and rigorous craftsmanship ... The artists' shared religious faith and values have constantly infused that tradition with meaning."[1]

Another contributor to the Encyclopedia of Mormonism is Martha Moffitt Peacock, Professor in Art History and Associate Director for the Center for the Study of Europe at Brigham Young University. In regards to Mormon art and its spiritual commonality, she wrote that this spirituality also encourages aesthetic diversity:

"Much discussion about a "Mormon aesthetic" has taken place in recent years, but it seems that the very personal nature of this spiritual artistic quest prevents the attainment of a prevalent aesthetic."[3]

Notable Mormon artists[]

- C. C. A. Christensen

- James C. Christensen, American illustrator[11]

- Caitlin Connolly, American painter and sculptor[12]

- Rose Datoc Dall, American painter[13]

- Avard Fairbanks

- Arnold Friberg, American illustrator and painter noted for his religious and patriotic works[14]

- Brian Kershisnik, American painter[15]

- Del Parson

- Walter Rane, American painter and illustrator[16]

- Jorge Cocco Santángelo, painter and professor of art from Argentina[17]

- Liz Lemon Swindle, painter and artist known for her religious paintings[18]

- Minerva Teichert, American painter and muralist[19]

- Stanley J. Watts

- Janis Mars Wunderlich, ceramic artist and professor of art at Monmouth College[20]

Popular non-Mormon artists used by the LDS Church[]

- Harry Anderson

- Carl Heinrich Bloch

- Heinrich Hofmann

See also[]

- List of Latter Day Saints: artists

- List of Utah artists

- List of Mormon Cartoonists

- Mormon folklore: Material objects

- Mormon literature

- Mormon music

- Phrenology's impact on Mormon artwork

- Symbolism in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Oman, Richard G. (1992), "Artists, Visual", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 70–73, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- ^ Niebergall, Chelsee, Worshiping through Art Archived May 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Church News and Events, August 5, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peacock, Martha Moffit (1992), "Art in Mormonism", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 73–75, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- ^ "Mormonads", churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ Strange, Corey, Interview of Richard Oman by Corey Strange, Mormon Artist.net

- ^ LDS International Art Competition

- ^ Church History Museum

- ^ Ninth International Art Competition,

- ^ Exhibit of Rare Rembrandt Etchings Opens at Church Museum, MormonNews Room.org,

- ^ Davis, Robert O., Rembrandt: The Biblical Etchings, The Ensign, Oct. 2005

- ^ Tad Walch and Scott Taylor. "Of Fantasy and Faith: LDS Artist James C. Christensen dies at age 74", Deseret News, Jan. 9, 2017

- ^ Jones, Morgan (April 25, 2018). "'A work in progress': Utah artist Caitlin Connolly on what art and infertility taught her about the worth of a soul". Deseret News. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Schmuhl, Emily. "LDS artist surprised at huge response to ad campaign", Deseret News, September 16, 2010. Retrieved on March 15, 2020.

- ^ Fulton, Ben. "Famed LDS/patriotic artist Friberg dead at 96". KSL.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Stack, Peggy Fletcher (April 5, 2014). "Angelic painting reminds Mormon mom she is not alone". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Merritt, Brett. "Book of Mormon stories: Paintings depict tender scenes of scripture", Daily Herald (Utah), September 4, 2004. Retrieved on April 9, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Ashely (June 5, 2018). "Argentine artist's paintings provide 'fresh' look at Christ's ministry". Deseret News. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Autry, Jennifer. "Life, challenges and art of Liz Lemon Swindle". Deseret News. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, Peter B. (Winter 2008). "Painting the Mormon Story". BYU Magazine. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (October 16, 2016). "The Competing Demands of Muse and Family". The New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

Further reading[]

- Compton, Todd (1992), "Symbolism", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 1428–1430, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- Cooper, Rex E. (1992), "Symbols, Cultural and Artistic", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 1430–1431, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- Savage, C. R. (1992), "Architecture", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 63–65, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

External links[]

- American art

- Mormon art