Moscone–Milk assassinations

| Moscone–Milk assassinations | |

|---|---|

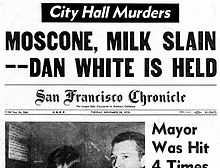

San Francisco Chronicle's front page for November 28, 1978 | |

City Hall Moscone–Milk assassinations (San Francisco) | |

| Location | City Hall, San Francisco, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 37°46′45″N 122°25′10″W / 37.77917°N 122.41944°WCoordinates: 37°46′45″N 122°25′10″W / 37.77917°N 122.41944°W |

| Date | November 27, 1978 |

| Target | George Moscone, Harvey Milk |

Attack type | Assassination, spree shooting |

| Weapons | .38-caliber Smith & Wesson Model 36 Chief's Special[1] |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Perpetrator | Dan White |

San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk were shot and killed in San Francisco City Hall by former Supervisor Dan White on November 27, 1978. White was angry that Moscone had refused to reappoint him to his seat on the Board of Supervisors, from which he had just resigned, and that Milk had lobbied heavily against his reappointment. These events helped bring national notice to then-Board President Dianne Feinstein, who became the first female mayor of San Francisco and eventually U.S. Senator for California.

White was subsequently convicted of voluntary manslaughter, rather than first-degree murder. The verdict sparked the "White Night riots" in San Francisco, and led to the state of California abolishing the diminished capacity criminal defense. It also led to the urban legend of the "Twinkie defense", as many media reports had incorrectly described the defense as having attributed White's diminished capacity to the effects of sugar-laden junk food.[2][3] White committed suicide in 1985, a little more than a year after his release from prison.

Preceding events[]

White had been a San Francisco police officer, and then later became a firefighter. He and Milk were each elected to the Board of Supervisors in the 1977 elections, which introduced district-based seats and ushered in the "most diverse Board the city has ever seen". The city charter prohibited anyone from retaining two city jobs simultaneously, so White resigned from his higher paying job with the fire department.[4]

With regard to business development issues, the 11-member board was split roughly 6–5 in favor of pro-growth advocates including White, over those who advocated the more neighborhood-oriented approach favored by Mayor Moscone. Debate among the Board members was sometimes acrimonious and saw White verbally sparring with other supervisors, including Milk and Carol Ruth Silver. Much of Moscone's agenda of neighborhood revitalization and increased city support programs was thwarted or modified in favor of the business-oriented agenda supported by the pro-growth majority on the Board.[citation needed]

Further tension between White and Milk arose with Milk's vote in favor of placing a group home within White's district. Subsequently, White would cast the only vote in opposition to San Francisco's landmark gay rights ordinance, passed by the Board and signed by Moscone in 1978. Dissatisfied with the workings of city politics, and in financial difficulty due to his failing restaurant business and his low salary as a supervisor, White resigned from the Board on November 10, 1978. The mayor would appoint his successor, which alarmed some of the city's business interests and White's constituents, as it indicated Moscone could tip the balance of power on the Board and appoint a liberal representative for the more conservative district. White's supporters urged him to rescind his resignation by requesting reappointment from Moscone and promised him some financial support. Meanwhile, some of the more liberal city leaders, most notably Milk, Silver, and then-California Assemblyman Willie Brown, lobbied Moscone not to reappoint White.[2][5]

On November 18, news broke of the mass deaths of members of Peoples Temple in Jonestown. Prior to the group's move to Guyana, Peoples Temple had been based in San Francisco, so most of the dead were recent Bay Area residents, including Leo Ryan, the United States Congressman who was murdered in the incident. The city was plunged into mourning, and the issue of White's vacant Board of Supervisors seat was pushed aside for several days.[6]

Assassinations[]

George Moscone[]

Moscone ultimately decided to appoint , a more liberal federal housing official, rather than reappoint White. On Monday, November 27, 1978, the day Moscone was set to formally appoint Horanzy to the vacant seat, White had an unsuspecting friend drive him to San Francisco City Hall. He was carrying a five-round .38-caliber Smith & Wesson Model 36 Chief's Special loaded with hollow-point bullets,[1] his service revolver from his work as a police officer, with ten extra rounds of ammunition in his coat pocket. White slipped into City Hall through a first floor window, avoiding the metal detectors. He proceeded to the mayor's office, where Moscone was conferring with Willie Brown.[7]

White requested a meeting with the mayor and was permitted to meet with him after Moscone's meeting with Brown ended. As White entered Moscone's outer office, Brown exited through another door. Moscone met White in the outer office, where White requested again to be reappointed to his former seat on the Board of Supervisors. Moscone refused, and their conversation turned into a heated argument over Horanzy's pending appointment.[8]

Wishing to avoid a public scene, Moscone suggested they retreat to a private lounge adjacent to the mayor's office, so they would not be overheard by those waiting outside. As Moscone lit a cigarette and proceeded to pour two drinks, White pulled out the revolver. He then fired shots at the mayor's shoulder and chest, tearing his lung. Moscone fell to the floor and White approached Moscone, pointed his gun 6 inches (150 mm) from the mayor's head, and fired two additional bullets into Moscone's ear lobes, killing him instantly.[9] While standing over the slain mayor, White reloaded his revolver. Witnesses later reported that they heard Moscone and White arguing, later followed by the gunshots that sounded like a car backfiring.[10][11]

Harvey Milk[]

Dianne Feinstein, who was then President of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, saw White immediately exit Mayor Moscone's office from a side door and called after him. White sharply responded with "I have something to do first."[9]

White proceeded to his former office, and intercepted Harvey Milk on the way, asking him to step inside for a moment. Milk agreed to join him.[12] Once the door to the office was closed, White positioned himself between the doorway and Milk, pulled out his revolver and opened fire on Milk. The first bullet hit Milk's right wrist as he tried to protect himself. White continued firing rapidly, hitting Milk twice more in the chest, then fired a fourth bullet at Milk's head, killing him, followed by a fifth shot into his skull at close range.[13]

White fled the scene as Feinstein entered the office where Milk lay dead. She felt Milk's neck for a pulse, her finger entering a bullet wound.[14] Horrified, Feinstein was shaking so badly she required support from the police chief after identifying both bodies.[15] Feinstein then announced the murders to a stunned public, stating: "As President of the Board of Supervisors, it's my duty to make this announcement. Both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed. The suspect is Supervisor Dan White."[16][17][18]

White left City Hall unchallenged and eventually turned himself in to Frank Falzon and another detective, former co-workers at his former precinct. He then recorded a statement in which he acknowledged shooting Moscone and Milk, but denied premeditation.[19]

Aftermath of the shootings[]

An impromptu candlelight march started in the Castro leading to the City Hall steps. Tens of thousands attended. Joan Baez led "Amazing Grace", and the San Francisco Gay Men's Chorus sang a solemn hymn by Felix Mendelssohn. Upon learning of the assassinations, singer/songwriter Holly Near composed "Singing for Our Lives", also known as "Song for Harvey Milk".[citation needed]

Moscone and Milk both lay in state at San Francisco City Hall. Moscone's funeral at St Mary's Cathedral was attended by 4,500 people. He was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma. Milk was cremated and his ashes were spread across the Pacific Ocean. Dianne Feinstein, as president of the Board of Supervisors, acceded to the Mayor's office, becoming the first female to serve in that office.

The coroner who worked on Moscone and Milk's bodies later concluded that the wrist and chest bullet wounds were not fatal, and that both victims probably would have survived with proper medical attention. However, the head wounds brought instant death without question, particularly because White fired at very close range.[20]

Trial and its aftermath[]

White was charged with first-degree murder with special circumstance, a crime which potentially carried the death penalty. White's defense team claimed that he was depressed at the time of the shootings, evidenced by many changes in his behavior, including changes in his diet. Inaccurate media reports said White's defense had presented junk food consumption as the cause of his mental state, rather than a symptom of it, leading to the derisive term "Twinkie defense"; this became a persistent myth when, in fact, defense lawyers neither argued junk food caused him to commit the shootings and Twinkies were only mentioned in passing. Rather, the defense argued that White's depression led to a state of mental diminished capacity, leaving him unable to have formed the premeditation necessary to commit first-degree murder. The jury accepted these arguments, and White was convicted of the lesser crime of voluntary manslaughter.[21]

The verdict proved to be highly controversial, and many felt that the punishment so poorly matched the deed and circumstances that most San Franciscans believed White essentially got away with murder.[22] In particular, many in the gay community were outraged by the verdict and the resulting reduced prison sentence. Since Milk had been homosexual, many felt that homophobia had been a motivating factor in the jury's decision. This groundswell of anger sparked the city's White Night riots.[21]

The unpopular verdict also ultimately led to changes by the legislature in 1981 and statewide voters in 1982 that ended California's diminished-capacity defense and substituted a somewhat different and slightly more limited "diminished actuality" defense.[23]

White was paroled in 1984 and committed suicide less than two years later.[24] In 1998, the San Jose Mercury News and San Francisco magazine reported that Frank Falzon, a homicide detective with the San Francisco police, said that he met with White in 1984. Falzon said that at that meeting, White confessed that not only was his killing of Moscone and Milk premeditated, but that he had actually planned to kill Silver and Brown as well. Falzon quoted White as having said, "I was on a mission. I wanted four of them. Carol Ruth Silver, she was the biggest snake ... and Willie Brown, he was masterminding the whole thing."[5][25] Falzon, who had been a friend of White's and who had taken White's initial statement at the time White turned himself in, said that he believed White's confession.[citation needed] White only made one statement of remorse. In a 1983 interview, he stated, "I guess they were nice guys. Too bad it happened."[26]

San Francisco Weekly has referred to White as "perhaps the most hated man in San Francisco's history".[22]

The revolver used, serial number 1J7901,[1] has gone missing from police evidence storage, possibly having been destroyed.[27]

Cultural depictions[]

Journalist Randy Shilts wrote a biography of Milk in 1982, The Mayor of Castro Street, which discussed the assassinations, trial and riots in detail.[28] The 1984 documentary film The Times of Harvey Milk won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[29]

Execution of Justice, a play by Emily Mann, chronicles the events leading to the assassinations.[30] The play opened on Broadway in March 1986 and in 1999, it was adapted to film for cable network Showtime, with Tim Daly portraying White.[31]

The Moscone–Milk assassinations and the trial of Dan White were lampooned by the Dead Kennedys with their re-written version of "I Fought the Law" which appeared in their 1987 compilation album Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death. The photo on the front cover of their 1980 album Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, which shows several police cars on fire, was taken during the White Night riots of May 21, 1979.[32]

The assassinations were the basis for a scene in the 1987 science fiction movie RoboCop in which a deranged former municipal official holds the mayor and others hostage and demands his job back.[33]

In 2003, the story of Milk's assassination and of the White Night Riot was featured in an exhibition created by the GLBT Historical Society, a San Francisco museum, archives and research center to which the estate of Scott Smith donated Milk's personal belongings that were preserved after his death. "Saint Harvey: The Life and Afterlife of a Modern Gay Martyr" was shown in the main gallery in the Society's former Mission Street location. The centerpiece was a section displaying the suit Milk was wearing at the time of his death.[34] The suit is currently on display in the Society's permanent museum space in the Castro.[35]

In 2008 the film Milk depicted the assassinations as part of a biographical story about the life of gay rights activist and politician Harvey Milk. The movie was a critical and commercial success, with Victor Garber portraying Moscone, Sean Penn playing Milk and Josh Brolin playing White. Penn won an Oscar for his performance and Brolin was nominated.[36]

In January 2012, the Berkeley Repertory Theater premiered Ghost Light, a play exploring the effect of Moscone's assassination on his son Jonathan, who was 14 at the time of his father's death. The production was directed by Jonathan Moscone himself and written by Tony Taccone.[37]

See also[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Weiss, Mike (December 8, 2002). "A CASE OF THE MISSING GUN / When famous murder weapons walk out of police evidence rooms, where do they go? We follow the disappearance of Dan White's gun". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pogash, Carol (November 23, 2003). "Myth of the 'Twinkie defense': The verdict in the Dan White case wasn't based on his ingestion of junk food". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- ^ "The Twinkie Defense". Snopes. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Geluardi, John (January 30, 2008). "Dan White's Motive More About Betrayal Than Homophobia – By – SF Weekly". SF Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weiss, Mike. (September 18, 1998). "Killer of Moscone, Milk had Willie Brown on List", San Jose Mercury News, p. A1.

- ^ Rapaport, Richard (November 16, 2003). "Jonestown and City Hall slayings eerily linked in time and memory / Both events continue to haunt city a quarter century later". SFGate. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Willie (November 18, 2008). "Brown remembers close call on tragic day". SFGate. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Turner, Wallace (November 28, 1978). "Suspect Sought Job", The New York Times, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street. Macmillan Publishing, p. 268.

- ^ Getlin, Josh (November 23, 2008). "Remembering George Moscone". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Gazis-Sax, Joel (1996). "The Martyrdom of Mayor George Moscone". www.notfrisco.com. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ "findarticles.com". findarticles.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street. Macmillan Publishing, p. 269.

- ^ Bruck, Connie (June 15, 2015). "Dianne Feinstein vs. the C.I.A." The New Yorker. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ Flintwick, James (November 28, 1978). "Aide: White 'A Wild Man'", The San Francisco Examiner, p. 1.

- ^ "The Times of Harvey Milk". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NikqzmwbgU for Dianne's announcement.

- ^ 1978 Year in Review: Assassination of Harvey Milk and George Moscone-http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1978/Assasination-of-Harvey-Milk-and-George-Moscone/12309251197005-13/

- ^ Kohler, Will (November 27, 2019). "In Memoriam: November 27, 1978: Harvey Milk Assassinated In San Francisco". Back2Stonewall. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street. Macmillan Publishing, p. 282.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pogash, Carol (November 23, 2003). "Myth of the 'Twinkie defense'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dan White's Motive More About Betrayal Than Homophobia. By John Geluardi. San Francisco Weekly. Published January 29, 2008.

- ^ Weinstock, MD, Robert; Leong, MD, Gregory B.; Silva, MD, J. Arturo (September 1, 1996). "California's Diminished Capacity Defense: Evolution and Transformation" (PDF). The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 24 (3): 347–366. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Lindsey, Robert (October 22, 1985). "DAN WHITE, KILLER OF SAN FRANCISCO MAYOR, A SUICIDE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Weiss, Mike. (October 1998). "Dan White's Last Confession", San Francisco Magazine

- ^ Gorney, Cynthia; parts, Second of two (January 4, 1984). "The Legacy of Dan White". Thr Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Mike (January 24, 2003). "Ex-clerk says he destroyed White's gun / Weapon used in assassinations was considered missing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ^ "The Mayor of Castro Street". Macmillian Publishers. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Murray, Noel. "The Times Of Harvey Milk documented the early days of a still-raging culture war". AV Club. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ ""Execution of Justice" Closes". NY Times. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Oxman, Steven. "Execution of Justice". Variety. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Lefebvre, Sam. "How San Francisco Punk Reacted to Harvey Milk and George Moscone's Deaths". KQED. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Booker, M. Keith (2006). Alternate Americas: Science Fiction Film and American Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 205. ISBN 0-275-98395-1.

- ^ Delgado, Ray (June 6, 2003). "Museum opens downtown with look at 'Saint Harvey'; exhibitions explore history of slain supervisor, rainbow flag". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ Sokol, Robert. "Castro museum reopens its door to LGBTQ history". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Gorman, Steve. "'Milk' screenwriter straddles two clashing worlds". Reuters. Retrieved November 25, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ Hurwitt, Robert. "'Ghost Light' review: Moscone haunted by events". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

References[]

- "Another Day of Death". Time Magazine. December 11, 1978. Archived from the original on March 10, 2008. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- "Dan White: SFPD Interrogation Audio (Nov. 27, 1978)". Bay Area Radio Museum, Gene D'Accardo/KNBR Collection. 1978. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- GAzis-SAx, Joel (1996). "The Martyrdom of George Moscone". notfrisco.com. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- Weiss, Mike (2010). Double Play: The Hidden Passions Behind the Double Assassination of George Moscone and Harvey Milk, Vince Emery Productions. ISBN 978-0-9825650-5-6.

- Milk, Harvey (2012). The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words, Vince Emery Productions. ISBN 978-0-9725898-8-8.

- 1978 in California

- 1978 in LGBT history

- 1978 in San Francisco

- 1978 murders in the United States

- Assassinations in the United States

- Crimes in San Francisco

- Harvey Milk

- LGBT history in San Francisco

- Murder in the San Francisco Bay Area

- November 1978 events in the United States

- Political history of the San Francisco Bay Area

- Violence against gay men