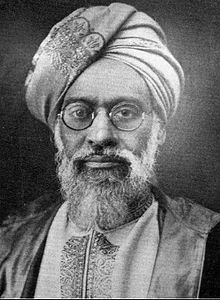

Mufti Muhammad Sadiq

Mufti Muhammad Sadiq | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | January 11, 1872 |

| Died | January 13, 1957 |

| Religion | Ahmadiyya Islam |

| Alma mater | University of London |

| Known for | Spreading Islam in North America |

| Occupation | Muslim Missionary, Religious Scholar, and Civil Rights Activist |

| hidePart of a series on

Ahmadiyya |

|---|

|

Mufti Muhammad Sadiq was a companion of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and the first Ahmadi missionary in the United States,[1] converted over seven hundred Americans to Ahmadism directly and over thousand indirectly.[2][3] His purpose, as a representative of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, was to convert Americans to Ahmadism and clear general misconceptions about it. Something that separated Mutfi Muhammad Sadiq from his contemporaries was the belief in racial integration between all racial and ethnic groups not just African Americans.[4][5] He was also important in trying to unite a hodgepodge of Muslim immigrants from Arabs to Bosnians to build mosques and have congregational prayer especially in Detroit and Chicago.[6]

Sadiq entered the US without any financial resources and embarked upon spreading the message of Islam in an area that was completely alien to his native culture. Consequently, he faced many difficulties, trials, and tribulations due to his skin color and religion. Sadiq also managed to establish the Moslem Sunrise the longest-running Muslim publication in America as well as writing many articles on Islam in various American periodicals and newspapers[7]

Missionary work[]

This section does not cite any sources. (May 2014) |

When Sadiq was in England, the second Ahmadi caliph directed him to establish the first Ahmadiyya mission in America. Sadiq sailed from England on January 26, 1920, and reached Philadelphia in the second week of February. The immigration department blocked his entry into the USA on the grounds that he was not allowed to polygyny in an effort to stop him to preach in America. He faced the situation with courage and patience and filed an appeal to the Department of Justice in Washington for entry. Sadiq made a distinction between commandments and permissions in Islam. He stated that all Muslims must follow the commandments of their religion, but may avoid the permissions. Polygyny is permitted only in countries whose laws sanction its practice. In countries that prohibit polygyny, permission for its practice is disallowed under the commandment that all Muslims must obey the laws of the country in which they live.

A dark-skinned man with a heavy grey beard, wearing a bright green turban and a grey coat with flowing sleeves, Sadiq presented quite a striking picture to the American public. He came at a time when race riots against black Americans rocked the nation's cities. Racial discrimination against Indian and Asian immigrants was also at an all-time high. Many racially oriented uprisings were directed against immigrants from the Punjab, whom white American called "ragheads" because they wore turbans. This was the challenging climate into which Sadiq came to win the people's hearts for Islam.

Sadiq was well suited for his role as preacher, writer and public speaker for the Ahmadiyya Movement in the United States. He had served as a missionary in England for a number of years and was a very learned man. He was a graduate of the University of London, a philologist of international repute and an expert in Arabic and Hebrew. He spoke seven languages and held six doctorate degrees.

Sadiq set up his first headquarters in April 1920 at 1897 Madison Avenue in New York City. By the end of May, he had made twelve new converts to the Ahmadiyya Movement: six from the Christian community and six from the Islamic immigrant community. S.W. Sobolewski was the first American woman converted by Sadiq to Islam in New York. He named her Fatima Mustafa, in fulfilment of a dream he had in England about an American female convert.

During his three years in America, Sadiq converted over seven hundred to Islam, from all racial, ethnic and religious groups. His missionary work was done through preaching and writing. By May 10, 1920, he had contributed twenty articles on Islam to various American periodicals and newspapers, among them The New York Times.

In October 1920, Sadiq moved the headquarters of the Ahmadiyya mission to Chicago because of its central location. He purchased a house in an affluent area of Chicago, at 4448 S. Wabash, and converted it to a mosque. In July 1921, he published the first issue of the Moslem Sunrise. This journal appeared every three months. Its purpose was to teach Islam and refute the misrepresentations of Islam that appeared in the American press.

Like many immigrants from the "darker races," Indian Muslims suffered discrimination in the United States. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community pointed to the race problem in the United States as proof that Americans needed Islam. The Ahmadis said that it was pitiful that the Christian teachings of brotherhood and equality had not been able to eliminate the evils of racism. Furthermore, the Ahmadis claimed that in Muslim countries people of all colours worshipped together so that there were never seats or mosques, which separated people based on race.

Because of its teaching and practice of universal brotherhood, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community attracted many black Americans, who assumed leadership roles within the movement. During this period, Mufti Muhammad Sadiq became friends with Jamaican born Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, (UNIA).

In 1923, Sadiq gave five lectures at the UNIA meetings in Detroit. Eventually, he converted forty Garveyites to the Ahmadiyya Muslim faith, among whom was Christian minister Sutton. Renamed Sheik Abdus Salaam, he was appointed leader of the Detroit branch of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Black Americans were told that Islam was the religion of their fore-parents before slavery. Apparently, through their connection with the UNIA's internationalist perspective, the Ahmadi Muslims had acquired a keen understanding of the ordinary black man that enabled them to connect Islam with Pan-Africanism and race pride. The adoption of Muslim names by all new converts was a further commitment to the Islamic world view as was the wearing of veils by some of the female converts.

References[]

- ^ Berg 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Turner 2003, pp. 124-125, 130.

- ^ Majid, Anouar. We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Others. p. 81.

- ^ Turner 2003, p. 116.

- ^ Berg 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Turner 2003, p. 121.

- ^ "The Muslim Sunrise - Mufti Muhammad Sadiq". muslimsunrise.com. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

Bibliography[]

- Berg, Herbert (2009). Elijah Muhammad and Islam.

- Turner, Richard Brent (2003). Islam in the African-American Experience.

- 1872 births

- Punjabi people

- Muslim missionaries

- People from Rabwah

- Pakistani Ahmadis