Museum of Art and Archeology of Périgord

Entrance to the museum | |

| |

| Established | 1835 |

|---|---|

| Location | 22, Cours Tourny 24000 Périgueux, France |

| Coordinates | 45°11′10″N 0°43′25″E / 45.18598°N 0.723671°ECoordinates: 45°11′10″N 0°43′25″E / 45.18598°N 0.723671°E |

| Type | Art museum |

| Website | www |

The Museum of Art and Archeology of Périgord, often abbreviated MAAP, is a municipal museum located in Périgueux. It is the oldest museum in the Dordogne department[1] and it includes over 2,000 square metres of permanent exhibition.

History[]

A first museum was established in 1804 in the city's Jesuit chapel by Count Wlgrin de Taillefer. In 1808, the increasing collection was moved to the Vomitorium of the arena of Périgueux and thence took the name of Vésunien Museum. Count Wlgrin de Taillefer died on February 2, 1833. In his will, he bequeathed his antiquities to Joseph de Mourcin, provided they be deposited in a museum which was to be built near the tower of Vésone, or in a museum in Paris.[2]

In 1835, upon the proposal of the mayor of Périgueux, the Museum of antiques and objets d'art's collection was transferred to the chapel of the White Penitents,[3] to the south of the cloister of the Saint-Front Cathedral. The museum took the name of "Archaeological Museum of Dordogne" in 1836 and became departmental thereafter. It was run by Joseph de Mourcin with the assistance of Abbé Audierne and Doctor Édouard Galyuntil until Mourcin's death. Doctor Galy succeeded Joseph de Mourcin upon his death.[4] He set up the museum in its current location, in the former Augustinian convent[5][6][7] used as a prison from 1808 to 1866, when it became in fact the museum's new site. The archaeological collection was gradually transferred there between 1869 and 1874.[8] Michel Hardy, president of the Historical and Archaeological Society of Périgord, succeeded Édouard Galy upon his death.

In 1857, a section dedicated to the fine arts was added to the museum's archaeological nucleus. It was then the only public collection of this nature in Dordogne. Mayor Alfred Bardy-Delisle created a municipal museum for painting and sculpture in Périgueux in 1859.[9][10] In 1891, upon the consistent bequeath of the Marquis de Saint-Astier of over 150 paintings (Flemish, French and Italian, from the 16th to the 19th century), the city decided to buy the old Augustinian convent, where the collection of the archaeological museum of the Dordogne department is now exhibited, and the buildings around it to create a new structure. On June 27, 1891, Gérard de Fayolle became curator of the municipal museum. In 1893, Gérard de Fayolle was appointed curator of the archaeological museum of the Dordogne department, replacing Michel Hardy who had been curator of that museum since 1887. The two museums were then in the old buildings of the Augustinian convent. In 1895, the General Council ceded the archaeological collection of the departmental museum to the city and made a significant financial contribution for the construction of a new museum.

The architectural competition for the new museum's house was launched in 1893. The current museum was built between 1895 and 1898 on the plans of the architect Charles Planckaert. The first stone was laid by the President of the Republic Félix Faure. In 1903, Gérard de Fayolle was appointed curator of the new museum of art and archaeology of Périgord, which he organized with the help of his assistant, Maurice Féaux, who had previously assisted Michel Hardy in organizing the collection of the department's archaeological museum.[11]

The archaeological collection was quickly expanded with geology, mineralogy, and prehistory collections as well as pieces from the medieval period resulting from research in Périgord. Archaeological pieces from North Africa (Egypt, Tunisia), Greece, Italy, Oceania, and the Americas were later added to the museum's main collection.

The museum has been a Monument historique of France since 2020.[12]

Collection[]

East wing[]

The east wing presents major works of medieval art such as a diptych from Rabastens dating to 1280[13] and a stained glass from the now lost 14th-century church of Saint-Silan;[14] works of art ranging from the 16th to the 20th century, which evoke the quality and characteristics of the works on display and the collections of non-European ethnography (seventh most important collection in France, with objects from Africa and Oceania).[15]

On the first floor are exhibited the collections of prehistory (fourth most important collection in France)[15] with numerous flint tools testifying to the human occupation in Périgord more than 400,000 years ago (Neanderthal fossil skeleton from the cave of Le Regourdou, Montignac, about 95,000 years old; a sapiens fossil skeleton , the so-called Chancelade man, about 12,000 years old; painted and carved blocks from the Blanchard des Roches shelter of the prehistoric site of Castel-Merle in Sergeac, 35,000 years old; stone with carved woman-figures from the prehistoric site of Termo-Pialat in Saint-Avit-Sénieur; the carved reindeer of Limeuil; a collection of Magdalenian bone carvings, including a carved rib from the Cro-Magnon shelter in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil and the bison bone pendant from the Raymonden shelter in Chancelade.[16][17]

Cloister[]

The cloister is a garden space that connects the east wing and the west wing of the museum, conceived for the presentation of the lapidary collection from the Gallo-Roman, medieval and Renaissance periods. It houses the remains of buildings from Périgueux and the Dordogne that have now disappeared (Romanesque sculptures from the disappeared church of San Frontone, dossals, decorations of private buildings, Merovingian and Carolingian sarcophagi, 13th and 14th century rhombus stones). The setting was inspired by a romantic envisioning of the ruins, typical of the time of their discovery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

West wing[]

The west wing of the museum houses the fine arts section, created in 1857 and enriched thanks to donations and purchases from local collections, from state deposits of artworks from the Louvre collection and from purchases of works from the exhibitions of the Paris Salons.

In 1891, after the aforementioned substantial donation from the Marquis of Saint-Astier, the wing meant to host this section was built, then renovated in 2002 with an installation in which the colors of the walls of the rooms were linked to the chronological period of the works: yellow for the hall of the eighteenth century and green for the hall in the Empire style of the early nineteenth century, light gray or bluish gray for the rooms dedicated to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with progressively lighter colors. In each room there are paintings, sculptures, furniture and art objects of the period, both local and illustrating the art of France, Flanders and Italy.

- 17th century French artworks: Siege of Namur by Jean-Baptiste Martin and two Battle Scenes by Jacques Courtois

- French works of the eighteenth century: Landscapes by Hubert Robert and Pierre Patel; End of a Storm by Adrien Manglard; Madonna and Child by Charles Antoine Coypel and other works by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Charles-Joseph Natoire and Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes

- Nineteenth-century French works: Adolphe Appian, Léon Bonnat, William Adolphe Bouguereau and Paul Guigou

- French works of the twentieth century: by the painters Maurice Marinot and Emile Othon Friesz and by the sculptors Jane Poupelet and Étienne Hajdu ;

- Flemish works: The Extraction of the Stone of Madness by Pieter Huys, still lifes by Jan Davidsz. de Heem and Jan van Huysum, works by Frans Floris and Abraham Bloemaert , Hooded Falcon by Jan Fyt, King Solomon Pays Homage to the God Moloch on Request of His Hundred Women, by Frans II Francken and Allegory of the Occasion, attributed to the latter's workshop; Landscape with Ruins by Bartholomeus Breenbergh

- Italian operas: Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus by Luca Giordano; artworks by Francesco Cairo; Seller of Fish by Giuseppe Recco; Muzio Scevola by Gaspare Diziani; The Wedding Feast at Cana by Sebastiano Ricci; The Grand Canal by Canaletto

- Spanish works: two paintings by Luis de Morales

- Porcelain: Capodimonte porcelain, 17th-century Chinese porcelain, Delftware, Chinese and Japanese porcelain dating to the nineteenth century; Limoges porcelain; works by the ceramist Pierre-Adrien Dalpayrat

Collection highlights[]

Saint James and Saint John the Evangelist by Luis de Morales. Early 16th century

Saint John the Baptist and Saint Paul by Luis de Morales. Early 16th century

A Surgeon Extracting the Stone of Folly by Pieter Huys. 1545-1577

Portrait de Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme. Anonyme by Unknown master. 16th century

Portrait d'un homme cuirassé by Unknown Florentine master. 16th century

Une fête de divinités marines by Frans Floris. 16th century

Allegorie de l'Occasion by Frans Francken the Younger. 1628

Saint Catherine of Siena by Francesco Cairo. Early 17th century

Fruits, dishes and lobster by Jan Davidszoon de Heem. Early 17th century

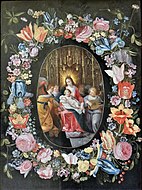

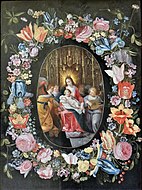

Madonna and Child in a Wreath of Flowers by Unknown Netherlandish master. Early 17th century

Le roi Salomon rendant grâce au dieu Moloch à la demande de ses cent femmes by Frans Francken the Younger. Early 17th century

Paysage au bord d'un fleuve by Abraham Bloemaert. Early 17th century

Décapitation de Saint Janvier by Scipione Compagno. Early 17th century

View of a Snowy Village by Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraaten. Early 17th century

Venus and Adonis by Unknown Venetian master. 17th century

Noces de Cana by Unknown Venetian master. 17th century

Still Life with Apples, a Lemon and Grapes by Juriaen van Streeck. 17th century

Siege of Namur by Jean-Baptiste Martin. 1693

Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus by Luca Giordano. ca. 1700

The End of the Storm by Adrien Manglard. Early 18th century

Portrait of Jean Nicolas de Boullongne by Louis Vigée. 1726-1787

The Unwinder by Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié. 18th century

Danaë by Charles-Joseph Natoire. 18th century

Vierge à l'Enfant by Charles Antoine Coypel. 1740

Le vieux pont sur le torrent by Hubert Robert. Late 18th century

Mars désarmé par les Grâces, circle of Jacques-Louis David. Late 18th century or early 19th century

Portrait of Madame Alfred Magne by Karl Ferdinand Sohn. Early 19th century

Maison des Consuls à Périgueux by Jules Coignet. 1833

Bétail au pâturage by Jacques Raymond Brascassat. Early 19th century

Chaumière sous les arbres à Auvers by Jean Achard. 19th century

View of Toledo by Adrien Dauzats. 19th century

Soul Carried to Heaven by William-Adolphe Bouguereau. ca. 1878

Notes[]

- ^ Petit Futé Dordogne. Petit Futé. 2009. ISBN 978-2-7469-2438-3..

- ^ Claude Lacombe, « Wlgrin de Taillefer (1761-1833), architecte utopiste et pionnier de l'archéologie périgourdine », dans Mémoire de la Dordogne, 1998, No. 11, p. 11 (lire en ligne).

- ^ The White Penitents obtained in 1817 to occupy the Small Mission, or former Small Seminary, which was located between the episcopal palace, the cloister of the cathedral, the attic of the chapter, the rue du Séminaire, the gardens and the courtyards. La Petite Mission gave the first formation to priests of the diocese before the Major Seminary (Guy Mandon, « Les séminaires du diocèse de Périgueux au XVIIIe siècle », in Annales du Midi, 1979, tome 91, No. 144, p. 497-500).

A private chapel was built there in the 18th century. In addition to the Petit Séminaire, the White Penitents also occupied the south wing of the cloister. The Black Penitents were installed in the southwest corner between 1817 and 1826. In 1821, the administration of the department ceded to the bishop most of the buildings remaining around the cloister to install the bishopric there. These buildings were destroyed in 1898 as part of the restoration work of the cathedral (Hélène Mousset, « Petit séminaire, Petite mission », in Hervé Gaillard, Hélène Mousset (dir.), Périgueux, Ausonius (collection Atlas historique des villes de France No. 53), Pessac, 2018, tome 2, Sites et Monuments, p. 444 ISBN 978-2-35613241-3). - ^ , « Visites au Musée d'antiquités de Périgueux », dans Congrès archéologique de France. 25e session. Périgueux et Cambrai. 1858, Société française d'archéologie, Paris, 1859, p. 259-282 (lire en ligne).

- ^ Le premier couvent des Augustins avait été fondé en 1484, hors les murs de la ville. Il a été détruit au

XVI. Il a été refondé en 1615 intra-muros. Saisi à la Révolution, il a servi de prison (Wlgrin de Taillefer, Antiquités de Vésone, tome 2, p. 593). - ^ , « Le couvent des Augustins de Périgueux », dans Bulletin de la , 1895, tome 22, p. 140-144 (lire en ligne).

- ^ Hélène Mousset, « Couvent des Augustins 2 », dans Hervé Gaillard, Hélène Mousset (dir.), Périgueux, Ausonius (collection Atlas historique des villes de France No. 53), Pessac, 2018, tome 2, Sites et Monuments, p. 407-408 ISBN 978-2-35613241-3.

- ^ Musée du Périgord : histoire

- ^ Catalogue des tableaux, dessins, statues, gravures et œuvres d'art du musée de la ville de Périgueux, imprimerie Dupont et Cie, Périgueux, 1875 (lire en ligne).

- ^ Édouard Galy, Suite du catalogue du Musée des tableaux et objets d'art de la ville de Périgueux, Imprimerie E. Laporte, Périgueux, 1886 (lire en ligne).

- ^ Michel Soubeyran, « À Périgueux, le Musée du Périgord », dans Paléo, Revue d'Archéologie Préhistorique, 1990, H-S Une histoire de la préhistoire en Aquitaine, p. 96-99 (lire en ligne).

- ^ Tiphanie Naud, « L'architecture du Maap reconnue », Sud Ouest édition Dordogne/Lot-et-Garonne, 22 mai 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Marquis de Fayolle, « Tableau de la confrérie de Rabastens », in Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 1922, p. 73-85 (read online).

- ^ , « Saint Sile (Silain), l'un des patrons de Périgueux (vitrail peint du XIVe siècle) », in Bulletin de la , 1875, tome 2, p. 264-266 (read online).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Le musée", at the museum's official website

- ^ Marquis de Fayolle, « Tableau de la confrérie de Rabastens », dans Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 1922, p. 73-85 (lire en ligne).

- ^ , « Saint Sile (Silain), l'un des patrons de Périgueux (vitrail peint du XIVe siècle) », dans Bulletin de la , 1875, tome 2, p. 264-266 (lire en ligne).

Bibliography[]

- , Catalogue du musée archéologique du département de la Dordogne, Imprimerie Dupont et Cie, Périgueux, 1862 (lire en ligne)

- , Suite du catalogue du Musée des tableaux et objets d'art de la ville de Périgueux, imprimerie E. Laporte, Périgueux, 1886 (lire en ligne)

- , « Verrerie gallo-romaine et grecque - Acquisitions pour la Musée de Périgueux », dans Bulletin de la , 1884, tome 11, p. 481 (lire en ligne)

- Auguste Allmer, « Périgueux », dans Revue épigraphique du Midi de la France, 1878, tome 1, p. 12-15, 37-46 (lire en ligne)

- « Inscriptions du musée lapidaire de Périgord. Civitas Petrucoriorum », dans Bulletin de la , 1882, tome 9, p. 80, 191-192, 294-296, 414-416, 515-520 (lire en ligne)

- , « Inscription du Musée de Périgueux mentionnant les Primani », dans Bulletin de la , 1878, tome 5, p. 176-185 (lire en ligne)

- Émile Espérandieu, Musée de Périgueux. Inscriptions antiques, imprimerie de la Dordogne, Périgueux, 1893 (lire en ligne)

- Maurice Féaux, Ville de Périgueux. Musée du Périgord. Catalogue de la série A : collections préhistoriques, Imprimerie D. Joucla, Périgueux, 1905 (lire en ligne)

- , Le Musée du Périgord, dans Congrès archéologique de France. 90e session. Périgueux. 1927, Société française d'archéologie, Paris, 1928, p. 128-134 (lire en ligne)

- André Coffyn, « L'Âge du Bronze au Musée du Périgord », , 1969, tome 12, fascicule 1, p. 83-120 (lire en ligne).

- M. et G. Ponceau, « La voûte en bois de la chapelle des Augustins à Périgueux », dans Bulletin de la , 1968, tome 95, 2e livraison, p. 130-132 (lire en ligne)

- Michel Soubeyran, Le Musée du Périgord, , 1971

- Christian Chevillot, « Le mobilier du tumulus de Chalagnac au Musée du Périgord et son contexte : le groupe tumulaire de Coursac », dans Bulletin de la , 1976, tome 103, 4e livraison, p. 285-299 (lire en ligne)

- Michel Soubeyran, « À Périgueux, le Musée du Périgord », , 1990, hors série, Lartet, Breuil, Peyroni et les autres. Une histoire de la préhistoire en Aquitaine, p. 96-99 (lire en ligne).

- Le Musée du Périgord, éditeur

- Michel Soubeyran, 1984, tome 1, « Vue d'ensemble »

- Françoise Soubeyran, 1986, tome 2, « Préhistoire »

- Michel Soubeyran, 1985, tome 3, « Antiquité et Gaule romaine »

- Françoise Soubeyran, 1989, tome 4, « Ethnographie exotique »

- Françoise Soubeyran, « Un reportage en direct : Le défilé au bison ? Historique de la pièce », dans Bulletin de la , 1994, tome 121, 2e livraison, p. 171-188 (lire en ligne)

- Sous la direction de J.-P. Bost, F. Didierjean, L. Maurin, J.-M. Roddaz, « Le Musée du Périgord », dans Guide archéologique de l'Aquitaine. De l'Aquitaine celtique à l'Aquitaine romane (VIe siècle av. J.-C.-XIe siècle apr. J.-C.), Éditions Ausonius, Pessac, 2004, p. 157-159 ISBN 978-2-910023-44-7

External links[]

- Art museums and galleries in France

- Museums in France

- 1st arrondissement of Lyon

- Archaeological museums in France

- Egyptological collections in France

- Museums in Dordogne

- Museums established in 1835

- 1835 establishments in France