National Day of Mourning (United States protest)

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (November 2020) |

The National Day of Mourning is an annual protest organized since 1970 by Native Americans of New England on the fourth Thursday of November, the same day as Thanksgiving in the United States. It coincides with an unrelated similar protest and counter-celebration, Unthanksgiving Day, held on the West Coast.

The organizers consider the national holiday of Thanksgiving Day as a reminder of the genocide and continued suffering of the Native American peoples. Participants in the National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. They want to educate Americans about history. The event was organized in a period of Native American activism and general cultural protests.[1] The protest is organized by the United American Indians of New England (UAINE). Since it was first organized, social changes have resulted in revisions to the portrayal of United States history,[citation needed] the government's and settlers' relations with Native American peoples,[citation needed] and a renewed appreciation for Native American culture.[citation needed]

Background[]

United American Indians of New England[]

The United American Indians of New England (UAINE) is a self-supporting and Native-led organization.[2] Their mission is to confront racism and fight for the freedom of political prisoners like Leonard Peltier.[2] Specifically, the UAINE fights back at "the racism of Pilgrim mythology perpetuated in Plymouth and the U.S. government's assault on poor people."[2] They also challenge the racist use of team names and mascots in sports. The UAE also wants to grow awareness of the Native struggle by speaking to classes in school and universities.[2] The United American Indians of New England argue that the Native American and colonial experience is misrepresented. They argue that the Pilgrims, rather than being portrayed as people fleeing persecution to an empty land and establishing a mutually beneficial relationship with the local inhabitants, arrived in North America and claimed tribal land for their own. In doing so, as part of a commercial venture, the UAINE believe that these settlers introduced sexism, racism, anti-homosexual bigotry, jails, and the class system.[3]

The UAINE also questions why the "First Thanksgiving" is not associated with Virginia, the first colony to hold such a celebration. They argue that the national myth of Thanksgiving cannot be built around the first harvest celebration because in doing so, we disregard the terrible circumstances that prevailed in the colony: settlers turning to cannibalism to survive. The UAINE argues that the only true element of the Thanksgiving story is that the Pilgrims would not have survived their first years in New England without the aid of the Wampanoag people or their already existing crops.[4]

Neither the UAINE nor the National Day of Mourning is sponsored by Wampanoag tribal leadership, although the tribe does not discourage members from participating. In his November 2014 message to the tribe, Mashpee Wampanoag Chief Qaqeemasq wrote "Historically, Thanksgiving represents our first encounter with the eventual erosion of our sovereignty and there is nothing wrong with mourning that loss. As long as we don't wallow in regret and resentment, it's healthy to mourn. It is a necessary part of the healing process."[5]

Initial protest[]

For the 350th anniversary in 1970 of the Pilgrim's arrival in North America (landing on Wampanoag land), the Commonwealth of Massachusetts planned to celebrate friendly relations between their ancestors and the Wampanoag. Wampanoag leader Wamsutta, also known as Frank James, was invited to make a speech at the celebration.[6] When his speech was reviewed by the anniversary planners,[7] they decided it would not be appropriate. The reason is given: "...the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place."[8]

Wamsutta based his speech on a Pilgrim's account of the first year in North America: a recollection of opening of graves, taking existing supplies of corn and bean and selling Wampanoag as slaves for 220 shillings each.[citation needed] After receiving a revised speech, written by a public relations person, Wamsutta decided he would not attend the celebration. To protest the attempted silencing of his position detailing the uncomfortable truth of the First Thanksgiving, he and his supporters went to neighboring Cole's Hill. Near the statue of Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag when the Pilgrims landed, and overlooking Plymouth Harbour and the Mayflower replica, Wamsutta gave his original speech. This was the first National Day of Mourning.[9]

Later protests[]

As a result, the UAINE organized an annual National Day of Mourning to be held in the same location. The objective is an effort to educate people about the history of the Wampanoag people,[4] raise awareness about the continued misrepresentation of Native American people and the colonial experience and the belief that people need to be educated about what happened rather than the national myth. The protest has also been used as a platform to address ongoing and contemporary struggles, as well as historical ones.

Attracting several hundred protestors each year, the National Day of Morning generally begins at noon and includes a march through the historic district of Plymouth. This is followed by speeches, although speakers are by invitation only. While the UAINE encourages people of all backgrounds to attend the protests, only Native speakers are invited to give these speeches about the past and current obstacles their people have overcome.[10] The protest concludes with a social time: Guests are asked to bring non-alcoholic beverages, desserts, fresh fruits and vegetables, or pre-cooked items. The protest is all-inclusive and open to anyone, and over the years has attracted other minority activists.

In 1996, the 'Latinos for Social Change' marched to the Plymouth Commons at the same time the Mayflower Society had their Pilgrim Progress parade, to show support for the UAINE. Police re-routed the Pilgrim parade to avoid conflict. In 1997, the Pilgrim Progress parade was held earlier and went undisturbed. Those who gathered to commemorate the 28th National Day of Mourning, in 1997, were met by police and state troopers. Some accounts allege that pepper spray was used on children and the elderly.[11][12] Twenty-five people were arrested on charges ranging from battery of a police officer to assembling without a permit. To avoid another conflict, the state settled with UAINE in October 1998.[12] The settlement stated that the UAINE is allowed to march without a permit, as long as advanced notice is provided to Plymouth.[13][14]

The 35th National Day of Mourning was held on November 25, 2004, and was dedicated to Leonard Peltier, a Native American activist convicted and sentenced to two consecutive terms of life imprisonment for first-degree murder in the shooting of two FBI agents. Many American Indians and supporters gathered again at the top of Coles Hill. They honored their Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. The 50th National Day of Mourning was held on November 28, 2019.[15] A 51st Annual National Day of Mourning (50th anniversary) march and speaker's program is planned for November 26, 2020, although the usual accompanying pot-luck social was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The event will also be streamed online with substantial prerecorded content on the UAINE.org website and elsewhere.[needs update][16][17]

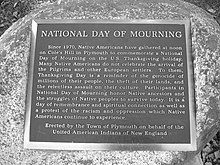

National Day of Mourning plaque[]

The town of Plymouth, Massachusetts has erected a plaque for National Day of Mourning. It is a rectangular metal plaque with beveled edges set in stone which reads:

NATIONAL DAY OF MOURNING

Since 1970, Native Americans have gathered at noon on Cole's Hill in Plymouth to commemorate a National Day of Mourning on the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday. Many Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers. To them, Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their cultures. Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression which Native Americans continue to experience.

Erected by the Town of Plymouth on behalf of the United American Indians of New England

References[]

- ^ Blansett, Kent (2018). A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "UAINE: background information". www.uaine.org. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ "United American Indians of New England". Uaine.org. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "First 'National Day of Mourning' Held in Plymouth". Mass Moments. Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. January 1, 2005. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ Cromwell, Cedric (November 4, 2014). "Tribal Health, Happiness and Prosperity…For that, I am Thankful". Archived from the original on November 24, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "The National Day of Mourning". Pilgrim Hall Museum. Archived from the original on July 2, 2003.

- ^ The suppressed speech of Wamsutta. To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970. (http://www.uaine.org/wmsuta.htm)

- ^ Source: UAINE

- ^ Kurtiş, Tuğçe; Adams, Glenn; Yellow Bird, Michael (2010). "Generosity or genocide? Identity implications of silence in American Thanksgiving commemorations". Memory. 18 (2): 208–224. doi:10.1080/09658210903176478. ISSN 0965-8211. PMID 19693724. S2CID 8270632.

- ^ Ritschel, Chelsea (November 22, 2018). "National Day of Mourning: How many Native Americans observe Thanksgiving?". The Independent. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Mehren, Elizabeth (December 3, 1997). "The Peace Pipe Eludes Modern 'Pilgrims' and Indians". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Karath, Mike (October 10, 1998). "Plymouth, Indian protesters settle over melee". Cape Cod Times.

- ^ Da Costa-Fernandes, Manuela (November 27, 1998). "American Indians stage peaceful Thanksgiving protest in Plymouth". The Standard-Times. New Bedford, Massachusetts. Associated Press.

- ^ Hanson, Fred (November 26, 2014). "Organizer of Day of Mourning protest in Plymouth says he won't quit". The Patriot Ledger. Quincy, Massachusetts.

- ^ "Native Americans holding 50th annual Day of Mourning on Thanksgiving". New York Post. Associated Press. November 26, 2019.

- ^ "National Day of Mourning". United American Indians of New England. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "United American Indians of New England". Facebook.

Additional reading[]

- Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond (1997).

- "Death by Disease" by Ann F. Ramenofsky in Archaeology (March/April 1992).

- Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War by Nathaniel Philbrick (2006).

- "Frank James (Wamsutta, 1923-2001) National Day of Mourning," in Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England edited by Siobhan Senior (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 455–458.

- David J. Silverman, This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving (New York: Bloomsbury, 2019).

- "Timeline," Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, https://mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/timeline.

- "Wampanoag History," Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), https://wampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/wampanoag-history.

- Christine M. DeLucia, Memory Lands: King Philip's War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018).

External links[]

- Public holidays in the United States

- Indigenous rights protests

- Observances based on the date of Thanksgiving (United States)

- Native American genocide

- Annual protests

- Thursday observances