Prejudice

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Prejudice[1] can be an affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership.[2] The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification of another person based on that person's perceived political affiliation, sex, gender, gender identity, beliefs, values, social class, age, disability, religion, sexuality, race, ethnicity, language, nationality, complexion, beauty, height, occupation, wealth, education, criminality, sport-team affiliation, music tastes or other personal characteristics.[3]

The word "prejudice" can also refer to unfounded or pigeonholed beliefs[4][5] and it may apply to "any unreasonable attitude that is unusually resistant to rational influence".[6] Gordon Allport defined prejudice as a "feeling, favorable or unfavorable, toward a person or thing, prior to, or not based on, actual experience".[7] Auestad (2015) defines prejudice as characterized by "symbolic transfer", transfer of a value-laden meaning content onto a socially-formed category and then on to individuals who are taken to belong to that category, resistance to change, and overgeneralization.[8]

Etymology[]

Historical approaches[]

The first psychological research conducted on prejudice occurred in the 1920s. This research attempted to prove white supremacy. One article from 1925 which reviewed 73 studies on race concluded that the studies seemed "to indicate the mental superiority of the white race".[9] These studies, along with other research, led many psychologists to view prejudice as a natural response to races believed to be inferior.

In the 1930s and 1940s, this perspective began to change due to the increasing concern about anti-Semitism due to the ideology of the Nazis. At the time, theorists viewed prejudice as pathological and they thus looked for personality syndromes linked with racism. Theodor Adorno believed that prejudice stemmed from an authoritarian personality; he believed that people with authoritarian personalities were the most likely to be prejudiced against groups of lower status. He described authoritarians as "rigid thinkers who obeyed authority, saw the world as black and white, and enforced strict adherence to social rules and hierarchies".[10]

In 1954, Gordon Allport, in his classic work The Nature of Prejudice, linked prejudice to categorical thinking. Allport claimed that prejudice is a natural and normal process for humans. According to him, "The human mind must think with the aid of categories... Once formed, categories are the basis for normal prejudgment. We cannot possibly avoid this process. Orderly living depends upon it."[11]

In the 1970s, research began to show that prejudice tends to be based on favoritism towards one's own groups, rather than negative feelings towards another group. According to Marilyn Brewer, prejudice "may develop not because outgroups are hated, but because positive emotions such as admiration, sympathy, and trust are reserved for the ingroup".[12]

In 1979, Thomas Pettigrew described the ultimate attribution error and its role in prejudice. The ultimate attribution error occurs when ingroup members "(1) attribute negative outgroup behavior to dispositional causes (more than they would for identical ingroup behavior), and (2) attribute positive outgroup behavior to one or more of the following causes: (a) a fluke or exceptional case, (b) luck or special advantage, (c) high motivation and effort, and (d) situational factors"/[10]

Youeng-Bruehl (1996) argued that prejudice cannot be treated in the singular; one should rather speak of different prejudices as characteristic of different character types. Her theory defines prejudices as being social defences, distinguishing between an obsessional character structure, primarily linked with anti-semitism, hysterical characters, primarily associated with racism, and narcissistic characters, linked with sexism.[13]

Contemporary theories and empirical findings[]

The out-group homogeneity effect is the perception that members of an out-group are more similar (homogenous) than members of the in-group. Social psychologists Quattrone and Jones conducted a study demonstrating this with students from the rival schools Princeton University and Rutgers University.[14] Students at each school were shown videos of other students from each school choosing a type of music to listen to for an auditory perception study. Then the participants were asked to guess what percentage of the videotaped students' classmates would choose the same. Participants predicted a much greater similarity between out-group members (the rival school) than between members of their in-group.

The justification-suppression model of prejudice was created by Christian Crandall and Amy Eshleman.[15] This model explains that people face a conflict between the desire to express prejudice and the desire to maintain a positive self-concept. This conflict causes people to search for justification for disliking an out-group, and to use that justification to avoid negative feelings (cognitive dissonance) about themselves when they act on their dislike of the out-group.

The realistic conflict theory states that competition between limited resources leads to increased negative prejudices and discrimination. This can be seen even when the resource is insignificant. In the Robber's Cave experiment,[16] negative prejudice and hostility was created between two summer camps after sports competitions for small prizes. The hostility was lessened after the two competing camps were forced to cooperate on tasks to achieve a common goal.

Another contemporary theory is the integrated threat theory (ITT), which was developed by Walter G Stephan.[17] It draws from and builds upon several other psychological explanations of prejudice and ingroup/outgroup behaviour, such as the realistic conflict theory and symbolic racism.[18] It also uses the social identity theory perspective as the basis for its validity; that is, it assumes that individuals operate in a group-based context where group memberships form a part of individual identity. ITT posits that outgroup prejudice and discrimination is caused when individuals perceive an outgroup to be threatening in some way. ITT defines four threats:

- Realistic threats

- Symbolic threats

- Intergroup anxiety

- Negative stereotypes

Realistic threats are tangible, such as competition for a natural resource or a threat to income. Symbolic threats arise from a perceived difference in cultural values between groups or a perceived imbalance of power (for example, an ingroup perceiving an outgroup's religion as incompatible with theirs). Intergroup anxiety is a feeling of uneasiness experienced in the presence of an outgroup or outgroup member, which constitutes a threat because interactions with other groups cause negative feelings (e.g., a threat to comfortable interactions). Negative stereotypes are similarly threats, in that individuals anticipate negative behaviour from outgroup members in line with the perceived stereotype (for example, that the outgroup is violent). Often these stereotypes are associated with emotions such as fear and anger. ITT differs from other threat theories by including intergroup anxiety and negative stereotypes as threat types.

Additionally, social dominance theory states that society can be viewed as group-based hierarchies. In competition for scarce resources such as housing or employment, dominant groups create prejudiced "legitimizing myths" to provide moral and intellectual justification for their dominant position over other groups and validate their claim over the limited resources.[19] Legitimizing myths, such as discriminatory hiring practices or biased merit norms, work to maintain these prejudiced hierarchies.

Prejudice can be a central contributing factor to depression.[20] This can occur in someone who is a prejudice victim, being the target of someone else's prejudice, or when people have prejudice against themselves that causes their own depression.

Paul Bloom argues that while prejudice can be irrational and have terrible consequences, it is natural and often quite rational. This is because prejudices are based on the human tendency to categorise objects and people based on prior experience. This means people make predictions about things in a category based on prior experience with that category, with the resulting predictions usually being accurate (though not always). Bloom argues that this process of categorisation and prediction is necessary for survival and normal interaction, quoting William Hazlitt, who stated "Without the aid of prejudice and custom, I should not be able to find my way my across the room; nor know how to conduct myself in any circumstances, nor what to feel in any relation of life".[21]

In recent years, researchers have argued that the study of prejudice has been traditionally too narrow. It is argued that since prejudice is defined as a negative affect towards members of a group, there are many groups against whom prejudice is acceptable (such as rapists, men who abandon their families, pedophiles, neo-Nazis, drink-drivers, queue jumpers, murderers etc.), yet such prejudices aren't studied. It has been suggested that researchers have focused too much on an evaluative approach to prejudice, rather than a descriptive approach, which looks at the actual psychological mechanisms behind prejudiced attitudes. It is argued that this limits research to targets of prejudice to groups deemed to be receiving unjust treatment, while groups researchers deem treated justly or deservedly of prejudice are overlooked. As a result, the scope of prejudice has begun to expand in research, allowing a more accurate analysis of the relationship between psychological traits and prejudice. [22][excessive citations]

Some researchers had advocated looking into understanding prejudice from the perspective of collective values than just as biased psychological mechanism and different conceptions of prejudice, including what lay people think constitutes prejudice.[23][24] This is due to concerns that the way prejudice has been operationalised does not fit its psychological definition and that it is often used to indicate a belief is faulty or unjustified without actually proving this to be the case.[25][26]

Types of Prejudice[]

One can be prejudiced against or have a preconceived notion about someone due to any characteristic they find to be unusual or undesirable. A few commonplace examples of prejudice are those based on someone's race, gender, nationality, social status, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation, and controversies may arise from any given topic.[citation needed]

Gender Identity[]

Transgender and non-binary people can be discriminated against because they identify with a gender that does not align with the their assigned sex at birth. Refusal to call them by their preferred pronouns, or claims that they are not the gender they identify as could be considered discrimination if it occurs in the right circumstances. Especially if the victim of this discrimination has expressed repetitively what their preferred identity is.[citation needed]

Gender Identity is now considered a protected category of discrimination. Therefore, severe cases of this discrimination can lead to criminal penalty or prosecution[citation needed](not to be confused with persecution; a term that is synonymous with discrimination.[citation needed]), and workplaces are required to protect against discrimination based on Gender Identity.[citation needed]

Sexism[]

Sexism, also called gender discrimination, is prejudice or discrimination based on a person's sex or gender(while related, these two concepts are not the same. Sex is based on an assessment of biological factors, while gender relates to one’s identity.[citation needed].) Sexism can affect any gender, but it is particularly documented as affecting women and girls more often (more broadly, the female[citation needed] [relates to sex, but can be used to describe the correlated gender of Homo sapiens. Although, it does not always match. See: Transgender, Non-binary, Gender identity, or the Gender identity section of this page for more information[citation needed]]).[27] The discussion of such sentiments, and actual gender differences and stereotypes continue to be controversial topics. Throughout history, women have been thought of as being subordinate to men, often being ignored in areas like the academia or belittled altogether. Traditionally, men were thought of as being more capable than women, mentally and physically.[28] In the field of social psychology, prejudice studies like the "Who Likes Competent Women" study led the way for gender-based research on prejudice.[28] This resulted in two broad themes or focuses in the field: the first being a focus on attitudes toward gender equality, and the second focusing on people's beliefs about men and women.[28] Today, studies based on sexism continue in the field of psychology as researchers try to understand how people's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors influence and are influenced by others.[citation needed]

Misandry (prejudice or discrimination towards men) and misogyny(prejudice or discrimination towards women) are two separate forms of sexism based on the gender of the victim.[citation needed] Although, misandry is more rarely used, and its existence is more up to debate than misogyny, it is still a form of sexism.[citation needed]

Nationalism[]

Nationalism is a sentiment based on common cultural characteristics that binds a population and often produces a policy of national independence or separatism.[29] It suggests a "shared identity" amongst a nation's people that minimizes differences within the group and emphasizes perceived boundaries between the group and non-members.[30] This leads to the assumption that members of the nation have more in common than they actually do, that they are "culturally unified", even if injustices within the nation based on differences like status and race exist.[30] During times of conflict between one nation and another, nationalism is controversial since it may function as a buffer for criticism when it comes to the nation's own problems since it makes the nation's own hierarchies and internal conflicts appear to be natural.[30] It may also serve a way of rallying the people of the nation in support of a particular political goal.[30] Nationalism usually involves a push for conformity, obedience, and solidarity amongst the nation's people and can result not only in feelings of public responsibility but also in a narrow sense of community due to the exclusion of those who are considered outsiders.[30] Since the identity of nationalists is linked to their allegiance to the state, the presence of strangers who do not share this allegiance may result in hostility.[30]

Classism[]

Classism is defined by dictionary.com as "a biased or discriminatory attitude on distinctions made between social or economic classes".[31] The idea of separating people based on class is controversial in itself. Some argue that economic inequality is an unavoidable aspect of society, so there will always be a ruling class.[32] Some also argue that, even within the most egalitarian societies in history, some form of ranking based on social status takes place. Therefore, one may believe the existence of social classes is a natural feature of society.[33]

Others argue the contrary. According to anthropological evidence, for the majority of the time the human species has been in existence, humans have lived in a manner in which the land and resources were not privately owned.[33] Also, when social ranking did occur, it was not antagonistic or hostile like the current class system.[33] This evidence has been used to support the idea that the existence of a social class system is unnecessary. Overall, society has neither come to a consensus over the necessity of the class system, nor been able to deal with the hostility and prejudice that occurs because of the class system.

Sexual discrimination[]

One's sexual orientation is the "direction of one's sexual interest toward members of the same, opposite, or both sexes".[34] Like most minority groups, homosexuals and bisexuals are not immune to prejudice or stereotypes from the majority group. They may experience hatred from others due to their sexual orientation; a term for such intense hatred based upon one's sexual orientation is homophobia. "Queer" may be used as an umbrella term for individuals in the LGBT+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and others). However, more specific words for discrimination directed towards specific sexualities exist under other names, such as biphobia.[35]

Due to what social psychologists call the vividness effect, a tendency to notice only certain distinctive characteristics, the majority population tends to draw conclusions like gays flaunt their sexuality.[36] Such images may be easily recalled to mind due to their vividness, making it harder to appraise the entire situation.[36] The majority population may not only think that homosexuals flaunt their sexuality or are "too gay", but may also erroneously believe that homosexuals are easy to identify and label as being gay or lesbian when compared to others who are not homosexual.[37]

The idea of heterosexual privilege has been known to flourish in society. Research and questionnaires are formulated to fit the majority; i.e., heterosexuals. The status of assimilating or conforming to heterosexual standards may be referred to as "heteronormativity", or it may refer to ideology that the primary or only social norm is being heterosexual.[citation needed]

In the US legal system, all groups are not always considered equal under the law. The gay or queer panic defense is a term for defenses or arguments used to defend the accused in court cases, that defense lawyers may use to justify their client's hate crime against someone that the client thought was LGBT. The controversy comes when defense lawyers use the victim's minority status as an excuse or justification for crimes that were directed against them. This may be seen as an example of victim blaming. One method of this defense, homosexual panic disorder, is to claim that the victim's sexual orientation, body movement patterns (such as their walking patterns or how they dance), or appearance that is associated with a minority sexual orientation provoked a violent reaction in the defendant. This is not a proven disorder, is no longer recognized by the DSM, and, therefore, is not a disorder that is medically recognized, but it is a term to explain certain acts of violence.[38]

Research shows that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a powerful feature of many labor markets. For example, studies show that gay men earn 10–32% less than heterosexual men in the United States, and that there is significant discrimination in hiring on the basis of sexual orientation in many labor markets.[39]

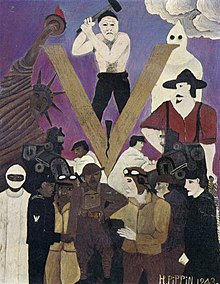

Racism[]

Racism is defined as the belief that physical characteristics determine cultural traits, and that racial characteristics make some groups superior.[40] By separating people into hierarchies based upon their race, it has been argued that unequal treatment among the different groups of people is just and fair due to their genetic differences.[40] Racism can occur amongst any group that can be identified based upon physical features or even characteristics of their culture.[40] Though people may be lumped together and called a specific race, everyone does not fit neatly into such categories, making it hard to define and describe a race accurately.[40]

Scientific Racism[]

Scientific racism began to flourish in the eighteenth century and was greatly influenced by Charles Darwin's evolutionary studies, as well as ideas taken from the writings of philosophers like Aristotle; for example, Aristotle believed in the concept of "natural slaves".[40] This concept focuses on the necessity of hierarchies and how some people are bound to be on the bottom of the pyramid. Though racism has been a prominent topic in history, there is still debate over whether race actually exists,[citation needed] making the discussion of race a controversial topic. Even though the concept of race is still being debated, the effects of racism are apparent. Racism and other forms of prejudice can affect a person's behavior, thoughts, and feelings, and social psychologists strive to study these effects.

Religious discrimination[]

While various religions teach their members to be tolerant of those who are different and to have compassion, throughout history there have been wars, pogroms and other forms of violence motivated by hatred of religious groups.[41]

In the modern world, researchers in western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic countries have done various studies exploring the relationship between religion and prejudice; thus far, they have received mixed results. A study done with US college students found that those who reported religion to be very influential in their lives seem to have a higher rate of prejudice than those who reported not being religious.[41] Other studies found that religion has a positive effect on people as far as prejudice is concerned.[41] This difference in results may be attributed to the differences in religious practices or religious interpretations amongst the individuals. Those who practice "institutionalized religion", which focuses more on social and political aspects of religious events, are more likely to have an increase in prejudice.[42] Those who practice "interiorized religion", in which believers devote themselves to their beliefs, are most likely to have a decrease in prejudice.[42]

Linguistic discrimination[]

Individuals or groups may be treated unfairly based solely on their use of language. This use of language may include the individual's native language or other characteristics of the person's speech, such as an accent or dialect, the size of vocabulary (whether the person uses complex and varied words), and syntax. It may also involve a person's ability or inability to use one language instead of another.[citation needed]

In the mid-1980s, linguist Tove Skutnabb-Kangas captured this idea of discrimination based on language as the concept of linguicism. Kangas defined linguicism as the ideologies and structures used to "legitimate, effectuate, and reproduce unequal division of power and resources (both material and non-material) between groups which are defined on the basis of language".[43]

Neurological discrimination[]

High-Functioning[]

Broadly speaking, attribution of low social status to those who do not conform to neurotypical expectations of personality and behaviour. This can manifest through assumption of 'disability' status to those who are high functioning enough to exist outside of diagnostic criteria, yet do not desire to (or are unable to) conform their behaviour to conventional patterns. This is a controversial and somewhat contemporary concept; with various disciplinary approaches promoting conflicting messages what normality constitutes, the degree of acceptable individual difference within that category, and the precise criteria for what constitutes medical disorder. This has been most prominent in the case of high-functioning autism,[44] where direct cognitive benefits increasingly appear to come at the expense of social intelligence.[45]

Discrimination may also extend to other high functioning individuals carrying pathological phenotypes, such as those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders. In these cases, there are indications that perceived (or actual) socially disadvantageous cognitive traits are directly correlated with advantageous cognitive traits in other domains, notably creativity and divergent thinking,[46] and yet these strengths might become systematically overlooked. The case for "neurological discrimination" as such lies in the expectation that one's professional capacity may be judged by the quality of ones social interaction, which can in such cases be an inaccurate and discriminatory metric for employment suitability.

Since there are moves by some experts to have these higher-functioning extremes reclassified as extensions of human personality,[47] any legitimisation of discrimination against these groups would fit the very definition of prejudice, as medical validation for such discrimination becomes redundant. Recent advancements in behavioural genetics and neuroscience have made this a very relevant issue of discussion, with existing frameworks requiring significant overhaul to accommodate the strength of findings over the last decade.[citation needed]

Low-Functioning[]

Assumptions may be made about the intelligence or value of individuals who have or exhibit behaviors of mental disorders or conditions. Individuals who have a difficult time assimilating or fitting into neurotypical standards and society may be label "Low-Functioning".

People with neurological disorders or conditions observed to have low intelligence, lack of self-control, suicidal behavior, or any number of factors may be discriminated on this basis. Institutions such as mental asylums, Nazi Concentration Camps, unethical pediatric research/care facilities, and eugenics labs have been used to carry out dangerous experiments or to torture the individuals involved.

Most discrimination today is characterized by individuals making comments towards low-functioning individuals or by harming them physically by themselves, but some institutions practice unsafe activities on these individuals.

Multiculturalism[]

Humans have an evolved propensity to think categorically about social groups, manifested in cognitive processes with broad implications for public and political endorsement of multicultural policy, according to psychologists Richard J. Crisp and Rose Meleady.[48] They postulated a cognitive-evolutionary account of human adaptation to social diversity that explains general resistance to multiculturalism, and offer a reorienting call for scholars and policy-makers who seek intervention-based solutions to the problem of prejudice.

Reducing prejudice[]

The contact hypothesis[]

The contact hypothesis predicts that prejudice can only be reduced when in-group and out-group members are brought together.[49][50] In particular, there are six conditions that must be met to reduce prejudice, as were cultivated in Elliot Aronson's "jigsaw" teaching technique.[49] First, the in- and out-groups must have a degree of mutual interdependence. Second, both groups need to share a common goal. Third, the two groups must have equal status. Fourth, there must be frequent opportunities for informal and interpersonal contact between groups. Fifth, there should be multiple contacts between the in- and the out-groups. Finally, social norms of equality must exist and be present to foster prejudice reduction.

Empirical research[]

Academics Thomas Pettigrew and Linda Tropp conducted a meta-analysis of 515 studies involving a quarter of a million participants in 38 nations to examine how intergroup contact reduces prejudice. They found that three mediators are of particular importance: Intergroup contact reduces prejudice by (1) enhancing knowledge about the outgroup, (2) reducing anxiety about intergroup contact, and (3) increasing empathy and perspective-taking. While all three of these mediators had mediational effects, the mediational value of increased knowledge was less strong than anxiety reduction and empathy.[51] In addition, some individuals confront discrimination when they see it happen, with research finding that individuals are more likely to confront when they perceive benefits to themselves, and are less likely to confront when concerned about others' reactions.[52]

Problems with psychological models[]

One problem with the notion that prejudice evolved because of a necessity to simplify social classifications because of limited brain capacity and at the same time can be mitigated through education is that the two contradict each other, the combination amounting to saying that the problem is a shortage of hardware and at the same time can be mitigated by stuffing even more software into the hardware one just said was overloaded with too much software.[53] The distinction between men's hostility to outgroup men being based on dominance and aggression and women's hostility to outgroup men being based on fear of sexual coercion is criticized with reference to the historical example that Hitler and other male Nazis believed that intergroup sex was worse than murder and would destroy them permanently which they did not believe that war itself would, i.e. a view of outgroup male threat that evolutionary psychology considers to be a female view and not a male view.[54][better source needed]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prejudice. |

| Look up prejudice, prejudgment, or bigotry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Prejudice |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: bigotry |

- Ambivalent prejudice

- Benevolent prejudice

- Bias

- Collective responsibility

- Common ingroup identity

- Conformity

- Fascism

- Hate crime

- Hostile prejudice

- Idée fixe (psychology)

- Milgram experiment

- Nazism

- Political correctness

- Prejudice from an evolutionary perspective

- Presumption of guilt

- Reverse discrimination

- Social influence

- Stigma management

- Suspension of judgment

- Terrorism

- Tolerance

- Totalitarianism

References[]

- ^ Douglas (Ph.D.), James (1872). English etymology. p. 67.

- ^ "Definition of PREJUDICE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Bethlehem, Douglas W. (2015-06-19). A Social Psychology of Prejudice. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-317-54855-3.

- ^ Turiel, Elliot (2007). "Commentary: The Problems of Prejudice, Discrimination, and Exclusion". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 31 (5): 419–422. doi:10.1177/0165025407083670. S2CID 145744721.

- ^ William James wrote: "A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices." Quotable Quotes – Courtesy of The Freeman Institute.

- ^ Rosnow, Ralph L. (March 1972). "Poultry and Prejudice". Psychologist Today. 5 (10): 53–6.

- ^ Allport, Gordon (1979). The Nature of Prejudice. Perseus Books Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-201-00179-2.

- ^ Auestad, Lene (2015). Respect, Plurality, and Prejudice (1 ed.). London: Karnac. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 9781782201397.

- ^ Garth, T. Rooster. (1930). "A review of race psychology". Psychological Bulletin. 27 (5): 329–56. doi:10.1037/h0075064.

- ^ a b Plous, S. "The Psychology of Prejudice". Understanding Prejudice.org. Web. 07 Apr. 2011.[verification needed]

- ^ Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.[page needed]

- ^ Brewer, Marilynn B. (1999). "The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love and Outgroup Hate?". Journal of Social Issues. 55 (3): 429–44. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00126.

- ^ Young-Bruehl, Elizabeth (1996). An Anatomy of Prejudices. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780674031913.

- ^ Quattrone, George A.; Jones, Edward E. (1980). "The perception of variability within in-groups and out-groups: Implications for the law of small numbers". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 38: 141–52. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.1.141.

- ^ Crandall, Christian S.; Eshleman, Amy (2003). "A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (3): 414–46. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.414. PMID 12784937.

- ^ Sherif, Muzafer; Harvey, O. J.; White, B. Jack; Hood, William R.; Sherif, Carolyn W. (1988). The Robbers Cave Experiment: Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6194-7.[page needed]

- ^ Stephan, Cookie White; Stephan, Walter C.; Demitrakis, Katherine M.; Yamada, Ann Marie; Clason, Dennis L. (2000). "Women's Attitudes Toward Men: an Integrated Threat Theory Approach". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 24: 63–73. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01022.x. S2CID 143906177.

- ^ Riek, Blake M.; Mania, Eric W.; Gaertner, Samuel L. (2006). "Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (4): 336–53. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4. PMID 17201592. S2CID 144762865.

- ^ Sidanius, Jim; Pratto, Felicia; Bobo, Lawrence (1996). "Racism, conservatism, Affirmative Action, and intellectual sophistication: A matter of principled conservatism or group dominance?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 70 (3): 476–90. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.474.1114. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.476.

- ^ Cox, William T. L.; Abramson, Lyn Y.; Devine, Patricia G.; Hollon, Steven D. (2012). "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression: The Integrated Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (5): 427–49. doi:10.1177/1745691612455204. PMID 26168502. S2CID 1512121.

- ^ Bloom, Paul "Can prejudice ever be a good thing" January 2014, accessed 02/12/17

- ^ Crandell, Christian S.; Ferguson, Mark A.; Bahns, Angela J. (2013). "Chapter 3: When We See Prejudice". In Stangor, Charles; Crendeall, Christian S. (eds.). Stereotyping and Prejudice. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1848726444.

- < Crawford, Jarret, and Mark J. Brandt. 2018. “Big Five Traits and Inclusive Generalized Prejudice.” PsyArXiv. June 30. doi:10.31234/osf.io/6vqwk.

- Brandt, Mark, and J. T. Crawford. "Studying a heterogeneous array of target groups can help us understand prejudice." Current Directions in Psychological Science (2019).

- Ferguson, Mark A., Nyla R. Branscombe, and Katherine J. Reynolds. "Social psychological research on prejudice as collective action supporting emergent ingroup members." British Journal of Social Psychology (2019).

- Brandt, Mark J., and Jarret T. Crawford. "Worldview conflict and prejudice." In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 61, pp. 1-66. Academic Press, 2020.

- Crawford, Jarret T., and Mark J. Brandt. "Who is prejudiced, and toward whom? The big five traits and generalized prejudice." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 45, no. 10 (2019): 1455-1467.

- ^ Platow, Michael J., Dirk Van Rooy, Martha Augoustinos, Russell Spears, Daniel Bar-Tal, and Diana M. Grace."Prejudice is about Collective Values, not a Biased Psychological System." Editor’s Introduction 48, no. 1 (2019): 15.

- ^ Billig, Michael. "The notion of “prejudice”: Some rhetorical and ideological aspects." Beyond prejudice: Extending the social psychology of conflict, inequality, and social change (2012): 139-157.

- ^ Brown, Rupert. Prejudice: Its social psychology. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- ^ Crawford, Jarret T., and Lee Jussim, eds. Politics of Social Psychology. Psychology Press, 2017.

- ^ There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism usually refers to discrimination against women, and primarily affects women. See, for example:

- "Sexism". New Oxford American Dictionary (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 9780199891535. Defines sexism as "prejudice, stereotyping, or discrimination, typically against women, on the basis of sex."

- "Sexism". Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Academic Edition. 2015. Defines sexism as "prejudice or discrimination based on sex or gender, especially against women and girls." Notes that "sexism in a society is most commonly applied against women and girls. It functions to maintain patriarchy, or male domination, through ideological and material practices of individuals, collectives, and institutions that oppress women and girls on the basis of sex or gender."

- Cudd, Ann E.; Jones, Leslie E. (2005). "Sexism". A Companion to Applied Ethics. London: Blackwell. Notes that "'Sexism' refers to a historically and globally pervasive form of oppression against women."

- Masequesmay, Gina (2008). "Sexism". In O'Brien, Jodi (ed.). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. SAGE. Notes that "sexism usually refers to prejudice or discrimination based on sex or gender, especially against women and girls." Also states that "sexism is an ideology or practices that maintain patriarchy or male domination."

- Hornsby, Jennifer (2005). "Sexism". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (2 ed.). Oxford. Defines sexism as "thought or practice which may permeate language and which assume's women's inferiority to men."

- "Sexism". Collins Dictionary of Sociology. Harper Collins. 2006. Defines sexism as "any devaluation or denigration of women or men, but particularly women, which is embodied in institutions and social relationships."

- "Sexism". Palgrave MacMillan Dictionary of Political Thought. Palgrave MacMillan. 2007. Notes that "either sex may be the object of sexist attitudes... however, it is commonly held that, in developed societies, women have been the usual victims."

- "Sexism". The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Love, Courtship, and Sexuality through History, Volume 6: The Modern World. Greenwood. 2007. "Sexism is any act, attitude, or institutional configuration that systematically subordinates or devalues women. Built upon the belief that men and women are constitutionally different, sexism takes these differences as indications that men are inherently superior to women, which then is used to justify the nearly universal dominance of men in social and familial relationships, as well as politics, religion, language, law, and economics."

- Foster, Carly Hayden (2011). "Sexism". In Kurlan, George Thomas (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Political Science. CQ Press. ISBN 9781608712434. Notes that "both men and women can experience sexism, but sexism against women is more pervasive."

- Johnson, Allan G. (2000). "Sexism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology. Blackwell. Suggests that "the key test of whether something is sexist... lies in its consequences: if it supports male privilege, then it is by definition sexist. I specify 'male privilege' because in every known society where gender inequality exists, males are privileged over females."

- Lorber, Judith (2011). Gender Inequality: Feminist Theories and Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 5. Notes that "although we speak of gender inequality, it is usually women who are disadvantaged relative to similarly situated men."

- Wortman, Camille B.; Loftus, Elizabeth S.; Weaver, Charles A (1999). Psychology. McGraw-Hill. "As throughout history, today women are the primary victims of sexism, prejudice directed at one sex, even in the United States."

- ^ a b c Dovidio, John, Peter Glick, and Laurie Rudman. On the Nature of Prejudice. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. 108. Print.

- ^ "Nationalism", dictionary.com

- ^ a b c d e f Blackwell, Judith; Smith, Murray; Sorenson, John (2003). Culture of Prejudice: Arguments in Critical Social Science. Toronto: Broadview Press. pp. 31–2. ISBN 9781551114903.

- ^ "Classism", dictionary.com

- ^ Blackwell, Judith, Murray Smith, and John Sorenson. Culture of Prejudice: Arguments in Critical Social Science. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2003. 145. Print.

- ^ a b c Blackwell, Judith, Murray Smith, and John Sorenson. Culture of Prejudice: Arguments in Critical Social Science. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2003. 146. Print.

- ^ "Sexual Orientation", dictionary.com

- ^ Fraïssé, C.; Barrientos, J. (November 2016). "The concept of homophobia: A psychosocial perspective". Sexologies. 25 (4): e65–e69. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2016.02.002. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Anderson, Kristin. Benign Bigotry: The Psychology of Subtle Prejudice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 198. Print.

- ^ Anderson, Kristin. Benign Bigotry: The Psychology of Subtle Prejudice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 200. Print.

- ^ Helmers, Matthew T. (June 2017). "Death and Discourse: The History of Arguing Against the Homosexual Panic Defense". Law, Culture and the Humanities. 13 (2): 285–301. doi:10.1177/1743872113479885. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Tilcsik, A (2011). "Pride and Prejudice: Employment Discrimination against Openly Gay Men in the United States". American Journal of Sociology. 117 (2): 586–626. doi:10.1086/661653. hdl:1807/34998. PMID 22268247. S2CID 23542996.

- ^ a b c d e Blackwell, Judith, Murray Smith, and John Sorenson. Culture of Prejudice: Arguments in Critical Social Science. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2003. 37–38. Print.

- ^ a b c Dovidio, John, Peter Glick, and Laurie Rudman. On the Nature of Prejudice. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. 413. Print.

- ^ a b Dovidio, John, Peter Glick, and Laurie Rudman. On the Nature of Prejudice. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. 414. Print.

- ^ Quoted in Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Phillipson, Robert, "'Mother Tongue': The Theoretical and Sociopolitical Construction of a Concept". In Ammon, Ulrich (ed.) (1989), Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties, p. 455. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 3-11-011299-X.

- ^ NeuroTribes: The legacy of autism and how to think smarter about people who think differently. Allen & Unwin. Print.

- ^ Iuculano, Teresa (2014). "Brain Organization Underlying Superior Mathematical Abilities in Children with Autism". Biological Psychiatry. 75 (3): 223–230. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.018. PMC 3897253. PMID 23954299.

- ^ Carson, Shelley (2011). "Creativity and Psychopathology: A Shared Vulnerability Model". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 56 (3): 144–53. doi:10.1177/070674371105600304. PMID 21443821.

- ^ Wakabayashi, Akio (2006). "Are autistic traits an independent personality dimension? A study of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) and the NEO-PI-R". Personality and Individual Differences. 41 (5): 873–883. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.003.

- ^ Crisp, Richard J.; Meleady, Rose (2012). "Adapting to a Multicultural Future". Science. 336 (6083): 853–5. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..853C. doi:10.1126/science.1219009. PMID 22605761. S2CID 21624259.

- ^ a b Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Akert, R. M. (2010). Social Psychology (7th edition). New York: Pearson.

- ^ Paluck, Elizabeth Levy; Green, Seth A; Green, Donald P (10 July 2018). "The contact hypothesis re-evaluated". Behavioural Public Policy. 3 (2): 129–158. doi:10.1017/bpp.2018.25.

- ^ Pettigrew, Thomas F.; Tropp, Linda R. (2008). "How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators". European Journal of Social Psychology. 38 (6): 922–934. doi:10.1002/ejsp.504.

- ^ Good, J. J.; Moss-Racusin, C. A.; Sanchez, D. T. (2012). "When do we confront? Perceptions of costs and benefits predict confronting discrimination on behalf of the self and others". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 36 (2): 210–226. doi:10.1177/0361684312440958. S2CID 143907822.

- ^ Rolf Pfeifer, Josh Bongard (2006). How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence

- ^ David Buller (2005). Adapting Minds: Evolutionary Psychology and the Persistent Quest for Human Nature

Further reading[]

- Adorno, Th. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J. and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

- BACILA, Carlos Roberto. Criminologia e Estigmas: Um estudo sobre os Preconceitos. São Paulo: Gen Atlas, 2016.

- Dorschel, A., Rethinking prejudice. Aldershot, Hampshire – Burlington, Vermont – Singapore – Sydney: Ashgate, 2000 (New Critical Thinking in Philosophy, ed. Ernest Sosa, Alan H. Goldman, Alan Musgrave et alii). – Reissued: Routledge, London – New York, NY, 2020.

- Eskin, Michael, The DNA of Prejudice: On the One and the Many. New York: Upper West Side Philosophers, Inc. 2010. (Next Generation Indie Book Award for Social Change)

- MacRae, C. Neil; Bodenhausen, Galen V. (2001). "Social cognition: Categorical person perception". British Journal of Psychology. 92 (Pt 1): 239–55. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.4390. doi:10.1348/000712601162059. PMID 11256766.

- Sherman, Jeffrey W.; Lee, Angela Y.; Bessenoff, Gayle R.; Frost, Leigh A. (1998). "Stereotype efficiency reconsidered: Encoding flexibility under cognitive load". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (3): 589–606. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.589. PMID 9781404.

- Kinder, Donald R.; Sanders, Lynn M. (1997). "Subtle Prejudice for Modern Times". Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. American Politics and Political Economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 92–160. ISBN 978-0-226-43574-9.

- Brandt, M; Crawford, J (2016). "Answering Unresolved Questions About the Relationship Between Cognitive Ability and Prejudice". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 7 (8): 884–892. doi:10.1177/1948550616660592. S2CID 147715632.

- Paluck, Elizabeth Levy; Porat, Roni; Clark, Chelsey S.; Green, Donald P. (2021). "Prejudice Reduction: Progress and Challenges". Annual Review of Psychology. 72 (1). doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-071620-030619.

- Amodio, David M.; Cikara, Mina (2021). "The Social Neuroscience of Prejudice". Annual Review of Psychology. 72 (1). doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050928.

- Prejudices

- Abuse

- Anti-social behaviour

- Barriers to critical thinking

- Prejudice and discrimination