Woke

Woke (/ˈwoʊk/ WOHK) is an English adjective meaning 'alert to racial prejudice and discrimination' that originated in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE). Beginning in the 2010s, it came to encompass a broader awareness of social inequalities such as sexism, and has also been used as shorthand for left-wing ideas involving identity politics and social justice, such as the notion of white privilege and slavery reparations for African Americans.

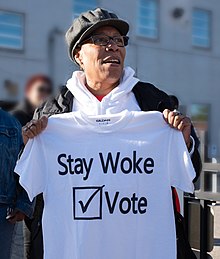

The phrase stay woke had emerged in AAVE by the 1930s, in some contexts referring to an awareness of the social and political issues affecting African Americans. The phrase was uttered in a recording by Lead Belly and later by Erykah Badu. Following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, the phrase was popularised by Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists seeking to raise awareness about police shootings of African Americans. After seeing use on Black Twitter, the term woke became an Internet meme and was increasingly used by white people, often to signal their support for BLM, which some commentators have criticised as cultural appropriation. Mainly associated with the millennial generation, the term spread internationally and was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2017.

The terms woke capitalism and woke-washing have arisen to describe companies who signal support for progressive causes as a substitute for genuine reform. By 2020, parts of the political center and right wing in several Western countries were using the term woke, often in an ironic way, as an insult for various progressive or leftist movements and ideologies perceived as over-zealous, performative, or insincere. In turn, some commentators came to consider it an offensive term with negative associations to those who promote political ideas involving identity and race.[1][2]

Origins and usage

"Wake Up Ethiopia! Wake up Africa! Let us work towards the one glorious end of a free, redeemed and mighty nation." —Marcus Garvey, Philosophy and Opinions (1923)[3][4][5]

In some varieties of African-American English, woke is used in place of woken, the usual past participle form of wake.[6] This has led to the use of woke as an adjective equivalent to awake, which has become mainstream in the United States.[6][7] To "stay woke" can express the intensified continuative and habitual grammatical aspect of African American Vernacular English (functioning like habitual be), in essence to always be awake, or to be ever vigilant.[8]

20th century

Black American folk singer-songwriter Huddie Ledbetter, a.k.a. Lead Belly, uses the phrase near the end of the recording of his 1938 song "Scottsboro Boys", which tells the story of nine black teenagers accused of raping two white women, saying: "I advise everybody, be a little careful when they go along through there – best stay woke, keep their eyes open."[9][10] Aja Romano writes at Vox that this represents "Black Americans' need to be aware of racially motivated threats and the potential dangers of white America".[4] J. Saunders Redding recorded a comment from an African American United Mine Workers official in 1940, stating: "Let me tell you buddy. Waking up is a damn sight harder than going to sleep, but we'll stay woke up longer."[11]

By the mid-20th century, woke had come to mean 'well-informed' or 'aware',[12] especially in a political or cultural sense.[6] The Oxford English Dictionary traces the earliest such usage to a 1962 New York Times Magazine article titled "If You're Woke You Dig It" by African-American novelist William Melvin Kelley, describing the appropriation of African American slang by white beatniks.[6]

Woke had gained more political connotations by 1971 when the play Garvey Lives! by Barry Beckham included the line: "I been sleeping all my life. And now that Mr. Garvey done woke me up, I'm gon' stay woke. And I'm gon help him wake up other black folk."[13][14] Marcus Garvey had himself exhorted his early 20th century audiences, "Wake up Ethiopia! Wake up Africa!"[5] Romano describes this as "a call to global Black citizens to become more socially and politically conscious".[4]

2000s and early 2010s, #Staywoke hashtag

Through the 2000s and early 2010s, woke was used either as a term for not literally falling asleep, or as slang for one's suspicions of being cheated on by a romantic partner.[4] In November 2016, the singer Childish Gambino released the song "Redbone", which used the term stay woke in reference to infidelity.[15] In the 21st century's first decade, the use of woke encompassed the earlier meaning with an added sense of being "alert to social and/or racial discrimination and injustice".[6]

This usage was popularized by soul singer Erykah Badu's 2008 song "Master Teacher",[7][12] via the song's refrain, "I stay woke".[13] Merriam-Webster defines the expression stay woke in Badu's song as meaning, "self-aware, questioning the dominant paradigm and striving for something better"; and, although within the context of the song, it did not yet have a specific connection to justice issues, Merriam-Webster credits the phrase's use in the song with its later connection to these issues.[7][17]

Songwriter Georgia Anne Muldrow, who composed "Master Teacher" in 2005, told Okayplayer news and culture editor Elijah Watson that while she was studying jazz at New York University, she learned the invocation Stay woke from Harlem alto saxophonist Lakecia Benjamin, who used the expression in the meaning of trying to "stay woke" because of tiredness or boredom, "talking about how she was trying to stay up – like literally not pass out". In homage, Muldrow wrote stay woke in marker on a T-shirt, which over time became suggestive of engaging in the process of the search for herself (as distinct from, for example, merely personal productivity).[18]

According to The Economist, as the term woke and the #Staywoke hashtag began to spread online, the term "began to signify a progressive outlook on a host of issues as well as on race".[19] In a tweet mentioning the Russian feminist rock group Pussy Riot, whose members had been imprisoned in 2012,[20][21] Badu wrote: "Truth requires no belief. Stay woke. Watch closely. #FreePussyRiot".[22][23][24] This has been cited by Know Your Meme as a one of the first examples of the #Staywoke hashtag.[25]

2010s: Black Lives Matter

Following the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, The phrase stay woke was used by activists of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement to urge awareness of police abuses.[4][26][25] The BET documentary Stay Woke, which covered the movement, aired in May 2016.[27] Within the decade of the 2010s, the word woke (the colloquial, passively voiced past participle of wake) obtained the meaning 'politically and socially aware'[28] among BLM activists.[6][26]

Broadening usage

While there is no single agreed-upon definition of woke, it came to be largely associated with ideas that involve identity and race and which are promoted by progressives, such as the notion of white privilege or slavery reparations for African Americans.[1] Vox's Aja Romano writes that woke evolved into a "single-word summation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice politics and critical race theory".[4] Columnist David Brooks wrote in 2017, "To be woke is to be radically aware and justifiably paranoid. It is to be cognizant of the rot pervading the power structures."[29] Sociologist contrasts woke with cool in the context of maintaining dignity in the face of social injustice: "While coolness is empty of meaning and interpretation and displays no particular consciousness, woke is explicit and direct regarding injustice, racism, sexism, etc."[30]

The term woke became increasingly common on Black Twitter, the community of African American users of the social media platform Twitter.[15] André Brock, a professor of black digital studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology, suggested that the term woke proved popular on Twitter because its brevity suited the platform's 140-character limit.[15] According to , the term began crossing over into general internet usage as early as 2015.[31] The phrase stay woke became an Internet meme,[17] with searches for woke on Google surging in 2015.[32]

The term increasingly came to be identified with members of the millennial generation.[15] In May 2016, MTV News identified woke as being among ten words teenagers "should know in 2016".[33][15] The American Dialect Society voted woke the slang word of the year in 2017.[34][35][36] In the same year, the term was included as an entry in Oxford English Dictionary.[37][6]

Scholars and argue that the phrase stay woke echoes Martin Luther King, Jr.'s exhortation to "to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change".[38]

Linguist Ben Zimmer writes that with mainstream currency, the term's "original grounding in African-American political consciousness has been obscured".[13] The Economist states that as the term came to be used more to describe white people active on social media, black activists "criticised the performatively woke for being more concerned with internet point-scoring than systemic change".[19] Journalist Amanda Hess says social media accelerated the word's cultural appropriation,[26] writing, "The conundrum is built in. When white people aspire to get points for consciousness, they walk right into the cross hairs between allyship and appropriation."[7][26] Hess calls woke "a back-pat from the left, a way of affirming the sensitive".[26]

Writer and activist Chloé Valdary has stated that the concept of being woke is a "double-edged sword" that can "alert people to systemic injustice" while also being "an aggressive, performative take on progressive politics that only makes things worse".[4] Social-justice scholars Tehama Lopez Bunyasi and Candis Watts Smith, in their 2019 book Stay Woke: A People's Guide to Making All Black Lives Matter, argue against what they term as "Woker-than-Thou-itis: Striving to be educated around issues of social justice is laudable and moral, but striving to be recognized by others as a woke individual is self-serving and misguided."[39][40][41] Essayist Maya Binyam, writing in The Awl, ironized about a seeming contest among players who "name racism when it appears" or who disparage "folk who are lagging behind".[26][further explanation needed]

While the term woke initially pertained to issues of racial prejudice and discrimination impacting African Americans, it was appropriated by other activist groups with different causes.[32] Abas Mirzaei, a senior lecturer in branding at Macquarie University says that the term "has been cynically applied to everything from soft drink to razors".[32]

The term woke has gained popularity amid an increasing leftward turn on various issues among the American left; this has partly been a reaction to the right-wing politics of U.S. President Donald Trump, who was elected in 2016, but also to a growing awareness regarding the extent of historical discrimination faced by African Americans.[42] Ideas that have come to be associated with wokeness include a rejection of American exceptionalism; a belief that the United States has never been a true democracy; that people of color suffer from systemic and institutional racism; that white Americans experience white privilege; that African Americans deserve reparations for slavery and post-enslavement discrimination; that disparities among racial groups, for instance in certain professions or industries, are automatic evidence of discrimination; that U.S. law enforcement agencies are designed to discriminate against people of color and so should be defunded, disbanded, or heavily reformed; that women suffer from ; that individuals should be able to identify with any gender or none; that U.S. capitalism is deeply flawed; and that Trump's election to the presidency was not an aberration but a reflection of the prejudices about people of color held by large parts of the U.S. population.[42] Although increasingly accepted across much of the American Left, many of these ideas were nevertheless unpopular among the U.S. population as a whole and among other, especially more centrist parts, of the Democratic Party.[42]

The impact of woke sentiment on society has been criticised from various perspectives. In 2018, the British political commentator Andrew Sullivan described the "Great Awokening", describing it as a "cult of social justice on the left, a religion whose followers show the same zeal as any born-again Evangelical [Christian]" and who "punish heresy by banishing sinners from society or coercing them to public demonstrations of shame".[32] In 2021, the British filmmaker and DJ Don Letts suggested that "in a world so woke you can't make a joke", it was difficult for young artists to make protest music without being accused of cultural appropriation.[43] By 2019 the term woke was increasingly being used in an ironic sense, reflected in two books published that year: Brendan O'Neill's Anti-Woke and the comedian Andrew Doyle's Woke, written as his fictional character Titania McGrath.[44]

In March 2021, Les Echos listed woke among eight words adopted by Generation Z that indicate "un tournant sociétal " ["a societal turning point"] in France.[45]

Woke as a pejorative term

Among American conservatives, woke has come to be used primarily as an insult.[46][1][4] In this pejorative sense, woke means "following an intolerant and moralising ideology."[19] British journalist Steven Poole comments that the term is used to mock "overrighteous liberalism".[47] Romano says that on the American right, "'woke' – like its cousin 'canceled' – bespeaks 'political correctness' gone awry".[4]

Opponents of progressive social movements often use the term mockingly or sarcastically,[4][48] implying that "wokeness" is an insincere form of performative activism.[46][4] Such critics often believe that movements such as Black Lives Matter exaggerate the extent of social problems.[48] Linguist and social critic John McWhorter argues that the history of woke is similar to that of politically correct, another term once used self-descriptively by the left which was appropriated by the right as an insult, in a process similar to the euphemism treadmill.[2]

Members of the U.S. Republican Party have been increasingly using the term to criticize members of the Democratic Party, while more centrist Democrats use it against more left-leaning members of their own party; such critics accuse those on their left of using cancel culture to damage the employment prospects of those who are not considered sufficiently "woke".[1]

FiveThirtyEight writer Perry Bacon Jr. suggests that this "anti-woke posture" is connected to a long-standing promotion of backlash politics by the Republican Party, wherein it promotes white and conservative fear in response to activism by African Americans as well as changing cultural norms.[49][1]

By 2021, woke had become used almost exclusively as a pejorative, with most prominent usages of the word taking place in a disparaging context.[1] The term woke, along with other terms such as cancel culture and critical race theory,[50] became a large part of Republican Party electoral strategy. Former President Donald Trump stated in 2021 that the Biden administration is "destroying" the country "with woke," and Republican Missouri Senator Josh Hawley used the term to promote his upcoming book by saying the "woke mob" was trying to suppress it.[46]

Woke capitalism and woke-washing

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (March 2021) |

By the mid-2010s, language associated with wokeness had entered the mainstream media and was being used for marketing.[37] The term woke capitalism was coined by writer Ross Douthat for brands that used inexpensive messaging as a substitute for genuine reform.[51] According to The Economist, examples of "woke capitalism" include advertising campaigns designed to appeal to millennials, who often hold more socially liberal views than earlier generations.[52] These campaigns were often perceived by customers as insincere and inauthentic and provoked backlashes.[32]

In 2020, cultural scientists Akane Kanai and Rosalind Gill described "woke capitalism" as the "dramatically intensifying" trend to include historically marginalized groups (currently primarily in terms of race, gender and religion) as mascots in advertisement with a message of empowerment to signal progressive values. On the one hand, this creates an individualized and depoliticized idea of social justice, reducing it to an increase in self-confidence. On the other hand, the omnipresent visibility in advertising can also amplify a backlash against the equality of precisely these minorities. These would become mascots not only of the companies using them, but of the unchallenged neoliberal economic system with its socially unjust order itself. For the economically weak, the equality of these minorities would thus become indispensable to the maintenance of this economic system; the minorities would be seen responsible for the losses of this system.[53]

See also

- African-American culture

- Political hip hop

- Social justice warrior

References

- ^ a b c d e f Bacon, Perry Jr. (17 March 2021). "Why Attacking 'Cancel Culture' And 'Woke' People Is Becoming The GOP's New Political Strategy". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ a b McWhorter, John (17 August 2021). "Opinion | How 'Woke' Became an Insult". The New York Times.

- ^ Cauley, Kashana (1 February 2019). "Word: Woke". The Believer. No. 123.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Romano, Aja (9 October 2020). "A history of 'wokeness'". Vox.

- ^ a b Garvey, Marcus; Garvey, Amy Jacques (1986) [first published 1923]. The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, Or, Africa for the Africans. Dover, Mass.: The Majority Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-912469-24-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g "New words notes June 2017". Oxford English Dictionary. 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Stay Woke: The new sense of 'woke' is gaining popularity". Words We're Watching. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2 February 2009). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century Five-volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5.

- ^ Matheis, Frank (August 2018). "Outrage Channeled in Verse". Living Blues. Vol. 49, no. 4. p. 15.

- ^ Lead Belly – "Scottsboro Boys" (song). SmithsonianFolkwaysRecordings. 2 July 2015. Event occurs at 4:26 – via YouTube.

- ^ Redding, J. Saunders (1942). "Southern Awakening". Negro Digest. Vol. 1. p. 43.

- ^ a b Krouse, Tonya; O'Callaghan, Tamara F. (2020). Introducing English Studies. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-350-05542-1.

- ^ a b c Zimmer, Ben (14 April 2017). "'Woke,' From a Sleepy Verb to a Badge of Awareness". Word on the Street. The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Beckham, Barry (1972). Garvey Lives!: A Play. OCLC 19687974.

- ^ a b c d e Marsden, Harriet (25 November 2019). "Whither 'woke': What does the future hold for word that became a weapon?". The New European.

- ^ Badu, Erykah (7 February 2019). "Master Teacher Medley" – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Pulliam-Moore, Charles (8 January 2016). "How 'woke' went from black activist watchword to teen internet slang". Splinter News.

- ^ Watson, Elijah C. (27 February 2018). "The Origin Of Woke: How Erykah Badu And Georgia Anne Muldrow Sparked The 'Stay Woke' Era". Okayplayer.

- ^ a b c "How has the meaning of the word 'woke' evolved?". The Economist explains. The Economist. 30 July 2021.

- ^ Parker, Suzi (14 September 2012). "Pussy Riot should continue their mission even if freed". The Washington Post.

- ^ Parker, Suzi (21 April 2012). "What American women could learn from Pussy Riot, a Russian punk rock girl band". The Washington Post.

- ^ Watson, Elijah C. (25 February 2020). "The Origin Of Woke: How The Death Of Woke Led To The Birth Of Cancel Culture". Okayplayer.

- ^ Holloway, James (31 October 2019). "Obama warns against social media call-out culture". New Atlas.

- ^ Badu, Erykah [@fatbellybella] (8 August 2012). "Truth requires no belief. Stay woke. Watch closely. #FreePussyRiot" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Richardson, Elaine; Ragland, Alice (Spring 2018). "#StayWoke: The Language and Literacies of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement". Community Literacy Journal. 12 (2): 27–56. doi:10.25148/clj.12.2.009099. ISSN 1555-9734.

- ^ a b c d e f Hess, Amanda (19 April 2016). "Earning the 'Woke' Badge". The New York Times Magazine. ISSN 0028-7822.

- ^ Holliday, Nicole (16 November 2016). "How 'Woke' Fell Asleep". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "wake". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Brooks, David (25 July 2017). "Opinion | How Cool Works in America Today". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Quoted in Morgan (2020), p. 277

- ^ Morgan, Marcyliena (2020). "'We Don't Play': Black Women's Linguistic Authority Across Race, Class, and Gender". In Alim, H. Samy; Reyes, Angela; Kroskrity, Paul V. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Language and Race. Oxford University Press. pp. 276–277. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190845995.013.13. ISBN 978-0-19-084599-5.

- ^ Hartley, John (2020). Communication, Cultural and Media Studies: The Key Concepts (5th ed.). Routledge. pp. 290–291. ISBN 978-1-3518-4801-5.

- ^ a b c d e Mirzaei, Abas (8 September 2019). "Where 'woke' came from and why marketers should think twice before jumping on the social activism bandwagon". The Conversation.

- ^ Trudon, Taylor (5 January 2016). "Say Goodbye To 'On Fleek,' 'Basic' And 'Squad' In 2016 And Learn These 10 Words Instead". MTV News.

- ^ Steinmetz, Katy (7 January 2017). "'Dumpster Fire' Is the American Dialect Society's 2016 Word of the Year". Time.

- ^ King, Georgia Frances (7 January 2017). "The American Dialect Society's word of the year is 'dumpster fire'". Quartz.

- ^ Metcalf, Allan (6 January 2017). "2016 Word of the Year is dumpster fire, as voted by American Dialect Society" (PDF) (Press release). American Dialect Society.

- ^ a b Sobande, Francesca (2019). "Woke-washing: 'Intersectional' femvertising and branding 'woke' bravery" (PDF). European Journal of Marketing. 54 (11): 2723–2745. doi:10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0134. ISSN 0309-0566. S2CID 213469381.

adverts span from 2015–2018, which reflects the point at which the language of 'woke(ness)' entered mainstream media and marketing spheres

- ^ Michael B., McCormack; Legal-Miller, Althea (2019). "All Over the World Like a Fever: Martin Luther King Jr.'s World House and the Movement for Black Lives in the United States and United Kingdom". In Crawford, Vicki L.; Baldwin, Lewis V. (eds.). Reclaiming the Great World House: The Global Vision of Martin Luther King Jr. University of Georgia Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8203-5602-0. JSTOR j.ctvfxv9j2.15.

- ^ Worth, Sydney (19 February 2020). "The Language of Antiracism". Yes! Magazine.

- ^ Bunyasi, Tehama Lopez; Smith, Candis Watts (2019). Stay Woke: A People's Guide to Making All Black Lives Matter. NYU Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4798-3648-2.

- ^ Spinelle, Jenna (19 June 2020). "Take Note: Authors Of 'Stay Woke' On Structural Racism, Black Lives Matter & How To Be Anti-Racist". WPSU.

- ^ a b c Bacon, Perry Jr. (16 March 2021). "The Ideas That Are Reshaping The Democratic Party And America". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ Thomas, Tobi (16 March 2021). "'Woke' culture is threat to protest songs, says Don Letts". The Guardian.

- ^ Shariatmadari, David (14 October 2019). "Cancelled for sadfishing: the top 10 words of 2019". The Guardian.

- ^ Belin, Soisic (29 March 2021). "Huit mots pour comprendre la génération Z" [Eight words to understand Generation Z]. Les Echos Start (in French).

- ^ a b c Smith, Allan; Kapur, Sahil (2 May 2021). "Republicans are crusading against 'woke'". NBC News.

- ^ Poole, Steven (25 December 2019). "From woke to gammon: buzzwords by the people who coined them". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Butterworth, Benjamin (21 January 2021). "What does 'woke' actually mean, and why are some people so angry about it?". inews.co.uk.

- ^ Kilgore, Ed (19 March 2021). "Is 'Anti-Wokeness' the New Ideology of the Republican Party?". Intelligencer (in American English). Vox Media.

- ^ Anderson, Bryan (2 November 2021). "Critical race theory is a flashpoint for conservatives, but what does it mean?". PBS NewsHour. Associated Press. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Helen (14 July 2020). "How Capitalism Drives Cancel Culture". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Woke, not broke". Bartleby. The Economist. Vol. 430, no. 9127. 26 January 2019. p. 65. ISSN 0013-0613.

- ^ Kanai, A.; Gill, R. (28 October 2020). "Woke? Affect, neoliberalism, marginalised identities and consumer culture". New Formations: A Journal of Culture, Theory & Politics. 102 (102): 10–27. doi:10.3898/NewF:102.01.2020. ISSN 0950-2378. S2CID 234623282.

Further reading

- Adams, Joshua (5 May 2021). "How 'Woke' Became a Slur". ColorLines.

- Hunt, Kenya (21 November 2020). "How 'woke' became the word of our era". The Guardian.

- Kelley, William Melvin (20 May 1962). "If You're Woke You Dig It; No mickey mouse can be expected to follow today's Negro idiom without a hip assist". Sunday Magazine. The New York Times. p. 45. ISSN 0028-7822.

- McCutcheon, Chuck (25 July 2016). "Speaking Politics word of the week: woke". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Peters, Mark (December 2016). "Woke". 2016 Words of the Year. The Boston Globe.

- "woke adjective earlier than 2008". Oxford English Dictionary. 25 June 2017.

External links

The dictionary definition of woke at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of woke at Wiktionary

- African-American English

- Black Lives Matter

- Social justice terminology

- American political catchphrases

- Political controversies

- 1940s neologisms