Nechells

| Nechells | |

|---|---|

The grade II listed public baths, opened 22 June 1910, on Nechells Park Road. | |

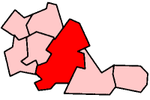

Nechells Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 33,957 (2011 Population Census) |

| • Density | 32.20 per ha |

| OS grid reference | SP095895 |

| Metropolitan borough |

|

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B7 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Nechells is a district ward in central Birmingham, England, whose population in 2011 was 33,957.[1] It is also a ward within the formal district of Ladywood. Nechells local government ward includes areas, for example parts of Birmingham city centre, which are not part of the historic district of Nechells as such, now often referred to in policy documents as "North Nechells, Bloomsbury and Duddeston".[2]

Origins of the name[]

Early recorded versions of the name include Echeles (about 1180), Le Echeles (1290) and Le Necheles (1322). The latter form of the name derives from "atten Eccheles", "belonging to the Eccheles", an Old English word meaning "land added to a village or estate".[3] The philologist Eilert Ekwall speculated that a more precise meaning could be "land added by clearing," or "land added by draining a marsh".[4] In the Middle English period, following the process of language change known as metanalysis, only the "n" in "atten" remained in oral usage and became assimilated to "Eccheles". So, n+Eccheles became the "Nechells" (pronunciation niːt͡ʃl̩z) of modern usage. However, the pronunciation net͡ʃl̩z was also current, as indicated by the spelling of Tomlinson's Map of Duddeston and Netchells, published in 1758.[5] This pronunciation was also to be heard in the 20th century amongst some older inhabitants of the area.[6]

The name "Nechells Green" originally referred to the triangle of land at the meeting point of the present Nechells Park Road, Nechells Place, Bloomsbury Street, Rocky Lane, Charles Arthur Street and Thimble Mill Lane. On Tomlinson's 1758 map the area was indeed shown as a village green surrounded by a few lanes and fields,[7] and a sparse population consisting of a handful of widely-spread homesteads.[8] In the 1950s and 60s the name was adopted for the re-developed area of Ashted, Duddeston and Vauxhall to the south-west of Nechells itself.[9]

History[]

The 19th century[]

Nechells became a densely populated area during the 19th century, with mass development of houses and factories taking place. Mass immigration occurred from Ireland. In 1868 it was described thus:

- ...a hamlet in the parish of Aston and borough of Birmingham, county Warwick. It is united with Duddeston, and forms a populous suburb of Birmingham. Here are extensive workshops for building railway carriages, also a lunatic asylum. The living (i.e. the position of vicar of the parish) is a perpetual curacy in the diocese of Worcester, value £59. The church is dedicated to St Clement.[10]

Developments in the Victorian era include the opening of the aforementioned St Clement's Church, designed by J. A. Chatwin, in 1859;[11] St Joseph's Roman Catholic Church in 1872 (incorporating the former chapel of the Roman Catholic cemetery, designed by A. W. Pugin and opened in 1850). The later church was designed by Pugin's son, E. W. Pugin;[12] a board school situated in Hutton (later Eliot) Street in 1879;[12] the building of almshouses adjacent to St. Clement's church to accommodate "31 inmates, widows, single women, and married couples - whose age is above 60"[13] and Bloomsbury Library of 1892 on Nechells Parkway, described as "a typical vigorous example of the red brick and terracotta school for municipal building at the end of the 19th century.".[14][15]

The London and North Western Railway's line from Stechford to Aston cut across Nechells Park Road and neighbouring streets when it opened in 1880,[18] as had the Grand Junction Railway from Liverpool and Manchester to Birmingham in order to reach its temporary terminus at Vauxhall in 1837.[12][18]

The 20th century and later[]

After World War II, further immigration occurred from parts of the Commonwealth, mostly the Caribbean and the Indian Sub Continent.[19]

By the 1950s, however, many of the homes in Nechells had been reduced to "slums" and were unfit for human habitation. People were living in homes without electricity, running water, bathrooms or indoor toilets. The Gas Works caused a continuous unpleasant smell. The bulk of the area had been designated as a redevelopment area in 1937, but its regeneration was put off by some 20 years due to World War II.[20]

The face of Nechells changed dramatically during the 1960s, with the decaying Victorian terraces being cleared and the area redeveloped with new houses and tower blocks. Some families remained in the new homes that had been built around Nechells, but there were insufficient new homes to rehouse all of the area's original residents, and as a result some families moved to new housing estates like Castle Vale and Chelmsley Wood. The new homes were certainly a big improvement on their predecessors, but the area still suffered from rising unemployment and crime.

The development of high rise flats in Nechells had actually started in the 1950s, and it was the home of Birmingham's very first tower block - Queens Tower, on Great Francis Street[21] - which was completed in 1954 and is still standing today.[22] However, many of the tower blocks in the Nechells area were demolished in the 1990s to make way for new low rise private and rented housing.[23]

The Siege of Austin Street[]

On 8 July 1961, the then vicar of St. Clement's, the Rev. Elwyn Evans, was called upon by police to assist them in negotiating with a man who had barricaded himself in his house and refused to come out until a clergyman was called. He had fired an unloaded air pistol from the window of his house in Austin Street. According to the Birmingham Post, several hundred people people had watched the police try to arrest the man who had effectively laid siege to the street. Rev. Evans eventually persuaded the man to give himself up and accompanied the unemployed man as he surrendered to the police. Rev. Evans, who served in Nechells from 1952 to 1964,[24] told reporters that had been taking a bath when the police arrived at his vicarage on Stanley Road.[25]

Austin Street itself, situated between Aston Church Road and Trevor Street at right angles to Nechells Park Road, no longer exists, having been built over by new housing.

Industrial and commercial development[]

Early evidence of industrial, or rather small-scale craft activity in Nechells is given on Tomlinson's 1758 map which shows a slitting mill used as a stage in the manufacture of nails situated at a point towards the northern end of what was to become Nechells Park Road.

On Ordnance Survey 1:2500 maps of 1902 and 1904 there is much evidence of industry in the early 20th century: Nechells Chemical Works and Birmingham Paper Mill were located adjacent to the Birmingham and Warwick Junction Canal at the eastern end of Cattells Grove; a Tube Works, Stove Works and Varnish Works were situated in an area bounded by the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, Holborn Hill and Long Acre; and a building shown as "Park Mills (Edge Tool)" is shown on Wharton Street, again adjoining the Birmingham and Warwick Junction Canal.

Later in the 20th century Nechells was chosen as the location of two gasworks, in Windsor Street and Nechells Place,

Two coal-fired power stations were situated on land now occupied by the Star City complex. The first power station was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1923 and a larger plant, known as Nechells "B", opened in 1954. The B station had a capacity of 224 megawatts (MW) and generated 52.869 GWh of electricity in 1980–81.[26] A small railway network was used by both power stations for the transport of coal from the main line railway at Saltley and within the plant. The power stations closed in 1982, but a steam locomotive used at the site, "Nechells No.4", has been preserved and is operating on the Chasewater Railway in Staffordshire[27][28]

The second of the two gasworks was the setting - in an "obscure suburb on the eastern side of Birmingham", according to one historian,[29] - for the so-called Battle of Saltley Gate in February 1972, a confrontation between striking mineworkers, the police and the West Midlands Gas Board over the picketing mineworkers' attempt to prevent the transport of coke from the gasworks. In labour history and mythology, the name "Saltley Gate" (or "Gates") has persisted, despite the locale for the incident being in Nechells.[30][31]

Nechells played a part in the development of the petrol-driven internal combustion motor car. At the age of twenty and with no formal qualifications, Frederick William Lanchester so impressed the owner of the Forward Gas Engine Company of Birmingham that he was offered the position of assistant works manager at their factory near Bloomsbury Street where he made various improvements to the equipment produced by this company. Lanchester resigned from the company in 1893 and went on to produce the first all-British four-wheel petrol car.[32] A sculpture, the Lanchester Car Monument, was built in Bloomsbury Village Green to commemorate Lanchester's work.[33]

Nearby, on Lingard Street, close to Bloomsbury Library, was situated another branch of the motor vehicle industry. David Haydon Ltd manufactured bodies for fire engines until the closure of the firm in the 1960s.[34]

Foundry Services Ltd, later FOSECO, moved into premises on Long Acre in 1933. The company had been created by two German Jewish refugees, Eric Weiss and Kossi Strauss, and specialized in the manufacture of fluxes and compounds used in the iron foundry industry. The firm moved to Tamworth in the 1990s and is now a multinational business.[35]

At the corner of Long Acre and Plume Street stood the large factory of Verity's Ltd, a manufacturer of electrical motors, fans and electrical fittings. The company went into voluntary liquidation in 1959.[36]

Flights Hallmark, a coach and corporate vehicle operator, has its head office and a depot on Long Acre, on the site of the former Aston motive power depot.[37]

The privately owned St Clements Nursing Home at the junction of Nechells Park Road and Stanley Road was built on land formerly occupied by St. Clement's Vicarage.[38][39]

A notable feature of the commercial life of present-day Nechells is the headquarters of the Wing Yip Chinese food and restaurant business which occupies a site at Nechells Green bounded by Thimblemill Lane,[40] Long Acre, Nechells Park Road and Railway Terrace.[41] This site opened in 1992, was expanded considerably in 1996 and now includes a business centre serving the Chinese community and a food superstore.[42]

Also on Thimble Mill Lane, the Aston Manor Brewery started production in 1993 and produces beer, cider and perry. It is capable of producing 24,000 bottles per hour.[43]

On 7 July 2016, five workers lost their lives when a concrete wall collapsed at the plant of Hawkeswood Metal Recycling on Trevor Street.[44]

Demographics and health[]

The 2011 Population Census found that 33,957 people lived in the ward with a population density of 3,400 people per km2. The broad ethnic breakdown of the population is: Asian 13.5%; White 15%; Black 65%; Mixed 3.5%; and others 3%. The largest ethnic groups are: White British (12%); Pakistani (9%); African (60%) mainly Somali,Sudanese and Eritrean; Caribbean (8%) and Bangladeshi (11%).

The Census also shows that Nechells has a young population with 29% of residents under 18 years old (compared with 25% in Birmingham as a whole). The median age of Nechells residents is 25 years as opposed to 32 years in Birmingham as a whole. Only 7% of people are 65 years or older (compared with 13% in Birmingham as a whole). More than half of the children growing up in Nechells are in families defined as being in child poverty.

Whilst it is notable in Birmingham for being the area with the highest rate of unemployment, crime and poverty, it has been the focus of a great deal of urban regeneration by Birmingham City Council and the former Birmingham Heartlands Development Corporation.

However, a report published in 2010 by the Birmingham Public Health Information Team concluded that:

- North Nechells, Bloomsbury and Duddeston has a young population compared with Birmingham overall

- The area is made up of multicultural, mixed communities with crime and health problems

- Life expectancy is much worse than the Birmingham average, along with self-reported health status and long term limiting illnesses

- More people die young in North Nechells, Bloomsbury and Duddeston than Birmingham on average, mostly from: chronic liver disease including cirrhosis, suicide, injury undetermined and stroke

- Mortality rates and admission rates (to hospital) are higher than the Birmingham average.[45]

Schools[]

Primary schools[]

Two primary schools in Nechells have acquired academy status. They are Nechells Primary E-ACT Academy[46] (the successor to Nechells Junior and Infants school and Hutton Street Board School before that) and Nechells Church of England Academy (the successor to St Clement's Church of England Primary School which opened next to St Clement's Church in Stuart Street in 1859).[47]

Secondary schools[]

Nechells Secondary Modern school, for pupils aged 11–16, which was incorporated into the existing Eliot Street Junior and Infants site after the passing of the 1944 Education Act, and with additional buildings on the adjoining Crompton Road, was closed and its buildings demolished in the 1980s.

Nechells is currently served by Heartlands Academy, the successor to Heartlands High School and Duddeston Manor School before that.[48]

Transport[]

Nechells is served by Duddeston railway station and Aston railway station. From 1856 to 1869, a station named "Bloomsbury and Nechells " was situated slightly to the north of the present Duddeston station.[49]

Bus service to Nechells began in the 1850s.[50] Osborne's railway timetable for January 1858 lists an omnibus service from the Town Hall to Nechells Green and Bloomsbury consisting of eight return journeys per day and operated by Lamyman and Monk. The fare was four pence.[51] These services were the distant forerunners of the main bus service serving Nechells in 2019, the National Express West Midlands bus route 66 from Birmingham city centre to Sutton Coldfield via Erdington.[52] This route is itself the successor of trolleybus route 7, which ran from the city centre to Nechells from 1922 to 1940 and the motorbus route 43 which replaced it in 1940.[53][54] The West Midlands bus route 8, the "Inner Circle", also serves the western part of the area.[55]

When the planned High Speed 2 rail line from London to Birmingham is constructed, it will skirt the south-eastern edge of Nechells, running alongside the Birmingham-Derby and under the Aston-Stechford railways and Aston Church Road before continuing to Saltley and a new Curzon Street station.[56] The site of the former Metro-Cammell works has been acquired for the construction of a depot and control centre for the new line.[57]

Places of interest[]

Nechells is home to Star City – a vast entertainment complex that houses shops, restaurants, a 22-lane bowling centre (Tenpin, formerly Megabowl), a casino, a hotel and Vue Cinema which, with thirty screens, is one of the largest multiplexes in Europe. Star City has been described as a "palace of pleasure...feeding and entertaining groups from families to young couples to children's parties".[58]

Community activities are now centred around Nechells POD, a charity established in 2015 with the aim of "offering a range of services and activities that will support, help, inspire, nurture and empower Nechells residents".[59] Based on Oliver Street, Nechells POD also offers houses Bloomsbury Library since library services were transferred from the original library Building. Sports facilities are provided at the Heartlands High Community Leisure Centre and the Nechells Community Sports Centre.

The Villa Tavern pub at the junction of Nechells Park Road and Holborn Hill displays the date "1897" as the year in which it was built. However, the present building dates from 1924 to 1925 and is a rebuilding of the original pub on this site by the architect Matthew J. Butcher. It is a Grade II listed building.[60]

Nechells Baths on Nechells Park Road is also Grade II listed. Plans for baths to be constructed in the Nechells ward came about in 1900 when representatives from the ward pressured the council into providing public baths for the ward. However, the Birmingham Baths Committee were already committed to other projects in the city and were unable to immediately attend the matter.

In 1903, a site at the corner of Nechells Park Road and Aston Church Road was acquired and in 1908, approval was given for the construction of baths on the site. Construction commenced that year and the baths were opened 22 June 1910. Facilities provided included a large swimming bath with a spectators' gallery and suites of private baths for men and women. The baths were immediately popular among the locals.

Refurbishment work to the baths was completed in May 2007 by Welconstruct. It cost £5.5 million, with funding from Advantage West Midlands, the Heritage Lottery Fund and ERDF.[61]

People[]

- Vanley Burke, Jamaican-born documentary photographer, best known for his photographs of Birmingham's African-Caribbean communities. In 2015, the contents of Burke's Nechells flat were put on display at the Ikon Gallery.[62][63]

- Paul Davies, Neil Marsh and John Rowlands. These Nechells residents were victims of the Birmingham Pub Bombings in November 1974. They were aged 20, 17 and 46 respectively at the time of their deaths.[64]

- Peter Fell, born in Nechells in 1951. Educated at Eliot Street Junior and Infants School, King Edward's Grammar School, Aston, Manchester University and Manchester Metropolitan University.[65] Fell has degrees in French and social work. He has worked as a teacher and social worker, founding the innovative "Revive" project, which provides support for refugees and asylum seekers, in 2001. He has published a book and papers in this field of social work practice.[66][67][68]

- Frederick William Lanchester (1868–1946), builder of the first British petrol-driven motor car. (See above).

- Catherine O'Flynn. Novelist, winner of the 2008 Costa First Novel Prize for What Was Lost.

- Edith Pitt (1900–66). Born at 68 St Clement's Road, Edith Pitt became an industrial welfare officer for Tubes Ltd. in 1943. She served as a Conservative city councilor for the Small Heath Ward in 1941 and was elected Conservative MP for Birmingham Edgbaston in 1953. She was made OBE in 1953 and DBE in 1962, having lost her post as parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Health in Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's cabinet, a position she had held since 1959.[69]

- Llion Rees, inspirational teacher and then head teacher of Nechells Junior School in the 1960s, described by his future colleague Sir David Winkley as a "brilliant primary head".[70][71]

- Peter Frederick Wagner, Anglican priest, born in 1931 and Vicar of St Clement's Nechells from 1964 to 1970. He later became Archdeacon of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe but was murdered in his church in Masvingo in 2001.[72]

Politics[]

Nechells ward is served by one Labour councillor, Tahir Ali.[73]

Nechells has adopted a Ward Support Officer.

References[]

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Nechells - UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Nechells Community First - Plans for Community First in Nechells 2013-2015" (PDF). thecommunityfirst.net. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ekwall, E. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960, p.169.

- ^ Ekwall, E.,"The English Place-Names Etchells, Nechells" in Mélanges de Philologie, offerts à M. Johan Vising par ses élèves et ses amis scandinaves, à l'occasion du soixante-dixième anniversaire de sa naissance, Gothenburg: N.J Gumperts and Paris: E.Champion, 1925, 105-6.

- ^ Chinn, C. The Streets of Brum, Part 4. Studley:Brewin, 2007, p.3.

- ^ Chinn, C. One Thousand Years of Brum. Birmingham: Birmingham Evening Mail, 1999, p. 103.

- ^ Chinn, The Streets of Brum p.3

- ^ Chinn, C. One Thousand Years of Brum. Birmingham: Birmingham Evening Mail, 1999, p. 103-4.

- ^ "Nechells Green". History of Birmingham Places A to Y. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ The National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland. London: James S. Virtue, 1868.

- ^ Dent, R.K. Old and New Birmingham. Birmingham: Houghton and Hammond 1880, P. 578

- ^ a b c Victoria History of the County of Warwick, Vol. VII. London: Oxford University Press, 1964

- ^ Dent, R.K. Old and New Birmingham. Birmingham: Houghton and Hammond 1880

- ^ Pevsner, N. and Wedgwood, A. The Buildings of England: Warwickshire. London: Penguin, 1966.

- ^ "Library Tickets". The Royal Literary Fund. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Bloomsbury Library Opening Times and Contact Details - Library of Birmingham". www.libraryofbirmingham.com. 1 February 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "The future of Bloomsbury Library in Nechells?". Birmingham Libraries Campaigns @FoLoB_. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ a b Clinker, C.R. Railways of the West Midlands: A Chronology. London: Stephenson Locomotive Society. 1954

- ^ Jones, Philip N. (1976). "Colored Minorities in Birmingham, England". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 66 (1): 89–103. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2562021.

- ^ "Nechells". History of Birmingham Places A to Y.

- ^ Bartlam, N. The Little Book of Birmingham. Stroud: The History Press, 2011, p.108.

- ^ Jones, P. "The suburban high flat in the post-war reconstruction of Birmingham, 1945–71". Urban History (32), pp.308-326 (2005).

- ^ "Nechells". www.emporis.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Crockford's Clerical Directory 1965, Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 384.

- ^ https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002134/19610710/522/0023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ CEGB (1981). CEGB Statistical Yearbook 1980-81. London: CEGB. p. 7.

- ^ "Nechells Power Station". www.warwickshirerailways.com. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Clawley, A. Birmingham Then and Now, Batsford, 2013, p.98

- ^ D.Sandbrook, State of Emergency - The Way We Were: Britain 1970-1974. Allen Lane, 2010, p.121

- ^ "R. Kellaway. Re-examining the Battle of Saltley Gate: interpretations of violence, leadership and legacy. University of Bristol, 2010" (PDF). www.bristol.ac.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) (registration required) - ^ "Battle of Saltley Gate". www.saltleygate.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Clark, C. S. (2004). "Lanchester, Frederick William [pseud. Paul Netherton-Herries] (1868–1946), car and aircraft designer and engineer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34388. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 1 June 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ A. Clawley, Birmingham Then and Now, Batsford, 2013, p.103

- ^ "David Haydon - Graces Guide". www.gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Lest We Forget Exhibition (Jewish Refugees) - Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk. 30 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Graces Guide". www.gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Action Blocked". www.vipcaoch.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Old Ordnance Survey Maps, Gravelly Hill 1902, Alan Godfrey Maps.

- ^ "St Clemens Nursing Home" (PDF). www.housingcare.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ See Chinn, 2007, pp3-4 for the origins of this street name.

- ^ Birmingham - The Photographic Atlas. London: HarperCollins, 2002, p.57.

- ^ "Wing Yip - Chinese Wholesale". www.wingyip.com.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Five men killed as wall collapses at Birmingham recycling centre". The Guardian. 8 July 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Baker, Andrew; Singh, Mohan; Begaj, Irena. "North Nechells, Bloomsbury and Duddeston Health Profile 2010. (PHIT-1011AB0019)" (PDF). www.bhwp.nhs.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Nechells Primary E-ACT Academy". Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Victoria County History of Warwickshire, Vol VII, p.529

- ^ "Heartlands Academy". Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Quick, M. Passenger Railway Stations in Great Britain: A Chronology. Oxford: Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2009

- ^ Jenson, A.G., Birmingham Transport, Birmingham Transport Historical Group, 1978.

- ^ Osborne's Railway Timetable and Literary Companion, January 1858,

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield to Birmingham via Boldmere, Erdington and Nechells" (PDF). nxbus.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Mayou, A., Barker, T. and Stanford, J. Birmingham Corporation Trams and Trolleybuses. Glossop: The Transport Publishing Company, 1982.

- ^ Keeley, M., Russell, M. and Gray, P. Birmingham City Transport. Glossop: The Transport Publishing Company, 1977.

- ^ Hanson, M., Harvey, D. and Drake, P. The Inner Circle - Birmingham's No. 8 Bus Route. Stroud: Tempus, 2002.

- ^ "Draft Environmental Statement | HS2". www.hs2.org.uk. 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Modern Railways, April 2017, p.76.

- ^ Farley, Paul (2012). Edgelands. Michael Symmons Roberts. London: Vintage. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-09-953977-3. OCLC 758982717.

- ^ "Home". Nechells POD.

- ^ "Britain's Historic Pub Interiors - Pub Heritage". pubheritage.camra.org.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Makeover is complete for Nechells Baths". Birmingham Post. 10 May 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "At Home with Vanley Burke | Ikon". www.ikon-gallery.org. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Young, Graham (9 January 2015). "Ikon Gallery: What 2015 has ready for the Brindleyplace gallery". BirminghamLive. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ D. McKittrick, S.Kelters, B. Feeney, C. Thornton and D. McVea, Lost Lives - The stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Mainstream Publishing, 2007, pp.499-500.

- ^ University, Manchester Metropolitan. "Meet Our Alumni, Manchester Metropolitan University". Manchester Metropolitan University. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Fell, P. (2004) "And now it has started to rain: Support and advocacy with adult asylum seekers in the voluntary sector" in Hayes, D. and Humphries, B. (eds) Social Work, Immigration and Asylum: Debates, Dilemmas and Ethical Issues for Social Work and Social Care Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley

- ^ "MAPPING OF MIGRATION, REFUGEE AND ASYLUM WORK IN AND FROM THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITY IN ENGLAND AND WALES – A REPORT SUMMARY". www.csan.org.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Williams, Jennifer (4 February 2016). "What it's really like to be an asylum seeker in Manchester". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Pitt, Dame Edith Maud (1906–1966), politician". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70451. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 1 June 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Knight of Passion, Times Educational Supplement". www.tes.co.uk. 11 May 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Click here to view the tribute page for Llion REES". funeral-notices.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Wagner, Hugh (20 March 2001). "Inside story: As an archdeacon in Zimbabwe, Peter Wagner devoted his life to helping others. Last month he was brutally murdered in his church". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Councillors' Advice Bureaux - Nechells Ward". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

Further reading[]

- Birmingham City Council. Nechells Ward Factsheet.[1]

- Chinn, Carl (ed.) Birmingham - Bibliography of a City. Birmingham: University of Birmingham Press, 2003.

- Chinn, Carl The Streets of Brum, vols 1–4. Studley: Brewin Books 2003–2007.

- Frostick, E. and Harland, L. Take Heart: people, history and change in Birmingham's Heartlands. Beverley: Hutton Press, 1993.

- Moth, J. The City of Birmingham Baths Department 1851 - 1951. Birmingham: Birmingham Corporation, 1951.

- Pevsner, N. and Wedgwood, A. The Buildings of England - Warwickshire. London: Penguin 1966.

- Rudge, T. and Clenton, K. Changing Nechells. Stroud, Fonthill Media, 2015.

- Thomson, N. Where I live - Inner City: Neil Thomson meets Desrene Gentles. London: Watts Books, 1993.

- Twist, Maria Saltley, Duddeston and Nechells. Stroud: Tempus 2001

External links[]

- A brief history of Nechells

- Millennium Point

- Aston University

- Birmingham City Council: Nechells Ward

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nechells. |

- ^ "Nechells Profile | Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk.

- Areas of Birmingham, West Midlands

- Wards of Birmingham, West Midlands