Negrito

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Isolated geographic regions in India and Maritime Southeast Asia | |

| Languages | |

| Andamanese languages, Aslian languages, Philippine Negrito languages | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, folk religions |

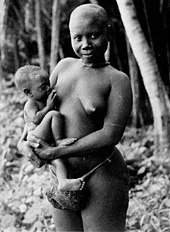

The term Negrito (/nɪˈɡriːtoʊ/) refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Maritime Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations classified as Negrito currenty include: the Andamanese peoples of the Andaman Islands, the Semang peoples (among them, the Batek people) of Peninsular Malaysia, the Maniq people of Southern Thailand, as well as the Aeta of Luzon Island, Ati and Tumandok of Panay Island, Agta of Sierra Madre and Mamanwa of Mindanao Island and about 30 other officially recognized ethnic groups in the Philippines.

Based on their physical similarities, Negritos were once considered a single population of closely related people. However genetic studies suggest that they consist of several separate groups, as well as displaying genetic heterogeneity. Negrito ethnic groups are genetically positioned in between South-Eurasian (Papuan-related) populations and East-Eurasian (East Asian-related) populations. The pre-Neolithic South-Eurasian populations of Southeast Asia were largely replaced by the expansion of various East-Eurasian populations, beginning about 50,000BC to 25,000BC years ago from Mainland Southeast Asia. The remainders, known as Negritos, form small minority groups in geographically isolated regions.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Historically they engaged in trade with the local population but were also often subjected to slave raids while also paying tributes to the local Southeast Asian rulers and kingdoms.[7]

Etymology[]

The word Negrito is the Spanish diminutive of negro, used to mean "little black person." This usage was coined by 16th-century Spanish missionaries operating in the Philippines, and was borrowed by other European travellers and colonialists across Austronesia to label various peoples perceived as sharing relatively small physical stature and dark skin.[8] Contemporary usage of an alternative Spanish epithet, Negrillos, also tended to bundle these peoples with the pygmy peoples of Central Africa, based on perceived similarities in stature and complexion.[8] (Historically, the label Negrito has also been used to refer to African pygmies.)[9] The appropriateness of using the label "Negrito" to bundle peoples of different ethnicities based on similarities in stature and complexion has been challenged.[8]

Many online dictionaries give the plural in English as either "Negritos" or "Negritoes," without preference. The plural in Spanish is "Negritos."[10][11]

Culture[]

Most Negrito groups lived as hunter-gatherers, while some also used agriculture. Today most Negrito groups live assimilated to the majority population of their homeland. Discrimination and poverty are often problems.[12]

Origins[]

Origin and ethnic relations[]

Negrito peoples descend from the first settlers of Southern Asia and Oceania, known as South-Eurasians in population genomics, as well as from early East-Eurasian lineages, which expanded from Mainland Southeast Asia into Insular Southeast Asia between 50,000BC to 25,000BC. Despite being isolated, the different peoples do share genetic similarities with their neighboring populations. They also show relevant phenotypic (anatomic) variations which require explanation.[13][14][4]

A recent genetic study found that unlike other early groups in Oceania, Andamanese Negritos lack Denisovan hominin admixture in their DNA. Denisovan ancestry is found among indigenous Melanesian and Aboriginal Australian populations at between 4–6%.[15][16]

Some studies have suggested that each group should be considered separately, as the genetic evidence refutes the notion of a specific shared ancestry between the "Negrito" groups of the Andaman Islands, the Malay Peninsula, and the Philippines.[17] Indeed, this sentiment is echoed in a more recent work from 2013 which concludes that "at the current level of genetic resolution ... there is no evidence of a single ancestral population for the different groups traditionally defined as 'Negritos'.[18]

Recent studies, concerning the population history of Southeast Asia, suggest that most modern Negrito populations in Southeast Asia show a rather strong East-Eurasian ancestry, ranging between 30% to 50% of their ancestry,[19] but are generally closest to other Oceanian populations, such as Papuans.[3][5]

Haplogroups[]

The main paternal haplogroup of the Negritos is K2b in the form of its rare primary clades K2b1* and K2b2*. Most Aeta males (60%) carry K-P397 (K2b1), which is otherwise uncommon in the Philippines and is strongly associated with the indigenous peoples of Melanesia and New Guinea.[20] Some Negrito populations also belong to sub-lineags of haplogroup D-M174 as well as Haplogroup O-M175, which are common among Andaman Islanders (65%), as well as the Maniq and the Semang in Malaysia.[21]

The Onge and all the Adamanan Islanders belong strictly to the mitochondrial Haplogroup M (a descendant of haplogroup L3, typically found in Africa). Haplogroup M is also the predominant marker of other Negrito tribes from Thailand and Malaysia, as well as Aboriginal Australians and Papuans,[22] and significant in African population of Somalis, Oromo, Tuaregs.[23][24][25][26] A 2009 study by the Anthropological Survey of India and the Texas Biomedical Research Institute identified seven genomes from 26 isolated ethnic groups from the Indian mainland, such as the Baiga tribe, which share "two synonymous polymorphisms with the M42 haplogroup, which is specific to Australian Aborigines". These were specific mtDNA mutations that are shared exclusively by Australian aborigines and these Indian tribes, and no other known human groupings.[27] Bulbeck (2013) shows the Andamanese maternal mtDNA is entirely mitochondrial Haplogroup M.[28][29]

Physical anthropology[]

Based on superficial similarities of a number of physical features – such as short stature, dark skin, scant body hair, and occasional steatopygia (large, curvaceous buttocks and thighs) – some scholars[who?] suggested a common origin for the Negrito and the Pygmies of Central Africa. The claim that the Andamanese more closely resemble African pygmies than other Austronesian populations in their cranial morphology in a study of 1973 added some weight to this theory, before genetic studies pointed to a closer relationship with their neighbours.[13]

Multiple studies also show that Negritos share a closer cranial affinity with Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians, but compared to them, are also strongly shifted towards East Asians.[30][31]

See also[]

Notes[]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Negritos". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References[]

- ^ S. Noerwidi, "Using Dental Metrical Analysis to Determine the Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene Population History of Java", in: Philip J. Piper, Hirofumi Matsumura, David Bulbeck (eds.), New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory (2017), p. 92.

- ^ Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (27 November 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a Regional Genetic Context: Reexamining the Evidence for an Early Peopling of the Archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1): 153–72. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 24297224. S2CID 7774927.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basu, Analabha; Sarkar-Roy, Neeta; Majumder, Partha P. (9 February 2016). "Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (6): 1594–1599. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.1594B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513197113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4760789. PMID 26811443.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Larena, Maximilian; Sanchez-Quinto, Federico; Sjödin, Per; McKenna, James; Ebeo, Carlo; Reyes, Rebecca; Casel, Ophelia; Huang, Jin-Yuan; Hagada, Kim Pullupul; Guilay, Dennis; Reyes, Jennelyn (30 March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13): e2026132118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (August 2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. hdl:10072/407535. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34433944.

- ^ Tagore, Debashree; Aghakhanian, Farhang; Naidu, Rakesh; Phipps, Maude E.; Basu, Analabha (29 March 2021). "Insights into the demographic history of Asia from common ancestry and admixture in the genomic landscape of present-day Austroasiatic speakers". BMC Biology. 19 (1): 61. doi:10.1186/s12915-021-00981-x. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC 8008685. PMID 33781248.

- ^ Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Manickham, Sandra Khor (2009). "Africans in Asia: The Discourse of 'Negritos' in Early Nineteenth-century Southeast Asia". In Hägerdal, Hans (ed.). Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-90-8964-093-2.

- ^ See, for example: Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911: "Second are the large Negrito family, represented in Africa by the dwarf-races of the equatorial forests, the Akkas, Batwas, Wochuas and others..." (p. 851)

- ^ "Definition of NEGRITO". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ "Negrito" – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "The succesful [sic] revival of Negrito culture in the Philippines". Rutu Foundation. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; et al. (21 January 2003), "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population", Current Biology, 13 (2): 86–93, doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01336-2, PMID 12546781, S2CID 12155496

- ^ Stock, JT (2013). "The skeletal phenotype of "negritos" from the Andaman Islands and Philippines relative to global variation among hunter-gatherers". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 67–94. doi:10.3378/027.085.0304. PMID 24297221. S2CID 32964023.

- ^ Reich; et al. (2011). "Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (4): 516–528. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. PMC 3188841. PMID 21944045.

- ^ "Oldest human DNA found in Spain – Elizabeth Landau's interview of Svante Paabo". CNN. 9 December 2013.

About 3% to 5% of the DNA of people from Melanesia (islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean), Australia and New Guinea as well as aboriginal people from the Philippines comes from the Denisovans.

- ^ Catherine Hill; Pedro Soares; Maru Mormina; Vincent Macaulay; William Meehan; James Blackburn; Douglas Clarke; Joseph Maripa Raja; Patimah Ismail; David Bulbeck; Stephen Oppenheimer; Martin Richards (2006), "Phylogeography and Ethnogenesis of Aboriginal Southeast Asians" (PDF), Molecular Biology and Evolution, 23 (12): 2480–91, doi:10.1093/molbev/msl124, PMID 16982817, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008

- ^ Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (1 February 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a regional genetic context: reexamining the evidence for an early peopling of the archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–172. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. ISSN 1534-6617. PMID 24297224. S2CID 7774927.

- ^ Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia - Lipson et al. (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2014/05/27/005603.full.pdf)

- ^ ISOGG, 2016, Y-DNA Haplogroup P and its Subclades – 2016 (20 June 2016).

- ^ Craniodental Affinities of Southeast Asia's "Negritos" and the Concordance with Their Genetic Affinities by David Bulbeck 2013

- ^ Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Lalji Singh, Alla G. Reddy, V. Raghavendra Rao, Subhash C. Sehgal, Peter A. Underhill, Melanie Pierson, Ian G. Frame, and Erika Hagelberg (2002), Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008, retrieved 16 November 2008CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Non, Amy. "ANALYSES OF GENETIC DATA WITHIN AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FRAMEWORK TO INVESTIGATE RECENT HUMAN EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY AND COMPLEX DISEASE" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ Holden. "MtDNA variation in North, East, and Central African populations gives clues to a possible back-migration from the Middle East". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Luísa Pereira; Viktor Černý; María Cerezo; Nuno M Silva; Martin Hájek; Alžběta Vašíková; Martina Kujanová; Radim Brdička; Antonio Salas (17 March 2010). "Linking the sub-Saharan and West Eurasian gene pools: maternal and paternal heritage of the Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.21. PMC 2987384. PMID 20234393.

- ^ Reich, David; Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Nick Patterson; Alkes L. Price; Lalji Singh (24 September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian Population History". Nature. 461 (7263): 489–494. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210. PMID 19779445.

- ^ Satish Kumar; Rajasekhara Reddy Ravuri; Padmaja Koneru; BP Urade; BN Sarkar; A Chandrasekar; VR Rao (22 July 2009), "Reconstructing Indian-Australian phylogenetic link", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 9: 173, doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-173, PMC 2720955, PMID 19624810,

In our completely sequenced 966-mitochondrial genomes from 26 relic tribes of India, we have identified seven genomes, which share two synonymous polymorphisms with the M42 haplogroup, which is specific to Australian Aborigines ... direct genetic evidence of an early colonization of Australia through south Asia

- ^ Bulbeck, David (November 2013). "Craniodental Affinities of Southeast Asia's "Negritos" and the Concordance with Their Genetic Affinities". Human Biology. 85 (1): 95–134. doi:10.3378/027.085.0305. PMID 24297222. S2CID 19981437.

- ^ Ghezzi; et al. (2005). "Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease in Italians". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (6): 748–752. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201425. PMID 15827561.

- ^ William Howells (1993). Getting Here: The Story of Human Evolution. Compass Press.

- ^ David Bulbeck; Pathmanathan Raghavan; Daniel Rayner (2006), "Races of Homo sapiens: if not in the southwest Pacific, then nowhere", World Archaeology, 38 (1): 109–132, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.534.3176, doi:10.1080/00438240600564987, ISSN 0043-8243, JSTOR 40023598, S2CID 84991420

Further reading[]

- Evans, Ivor Hugh Norman. The Negritos of Malaya. Cambridge [Eng.]: University Press, 1937.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2013. 'Why have the Peninsular "Negritos" remained distinct?’ Human Biology 85: 445–484. [ISSN 0018-7143 (print), 1534-6617 (online)]

- Garvan, John M., and Hermann Hochegger. The Negritos of the Philippines. Wiener Beitrage zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik, Bd. 14. Horn: F. Berger, 1964.

- Hurst Gallery. Art of the Negritos. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hurst Gallery, 1987.

- Khadizan bin Abdullah, and Abdul Razak Yaacob. Pasir Lenggi, a Bateq Negrito Resettlement Area in Ulu Kelantan. Pulau Pinang: Social Anthropology Section, School of Comparative Social Sciences, Universití Sains Malaysia, 1974.

- Mirante, Edith (2014). The Wind in the Bamboo: Journeys in Search of Asia's 'Negrito' Indigenous Peoples. Bangkok, Orchid Press.

- Schebesta, P., & Schütze, F. (1970). The Negritos of Asia. Human relations area files, 1–2. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files.

- Armando Marques Guedes (1996). Egalitarian Rituals. Rites of the Atta hunter-gatherers of Kalinga-Apayao, Philippines, Social and Human Sciences Faculty, Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

- Zell, Reg. About the Negritos: A Bibliography. Edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg. Negritos of the Philippines. The People of the Bamboo - Age - A Socio-Ecological Model. Edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg, John M. Garvan. An Investigation: On the Negritos of Tayabas. Edition blurb, 2011.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Negrito. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Negritos. |

- Negritos of Zambales—detailed book written by an American at the turn of the previous century holistically describing the Negrito culture

- Andaman.org: The Negrito of Thailand

- The Southeast Asian Negrito

- Negritos

- Demographics of the Philippines

- Ethnic groups in Malaysia

- Ethnic groups in Thailand

- Ethnic groups in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Ethnic groups in the Philippines

- Indigenous peoples of South Asia

- Indigenous peoples of Southeast Asia

- Austronesian peoples