New Brandeis movement

The New Brandeis or neo-Brandeis movement is an anti-trust academic and political movement in the United States that suggests monopolies naturally concentrate power among several individuals.[1] Also called hipster antitrust, the movement would have United States antitrust law seek to improve business market structures that negatively affect market competition, income inequality, consumer rights, unemployment, and wage growth. It advocates that antitrust laws should reduce focus on short-term price effects of mergers, and instead seek to improve the market conditions necessary to promote real competition.

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

|

| Anti-competitive practices |

|

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

History[]

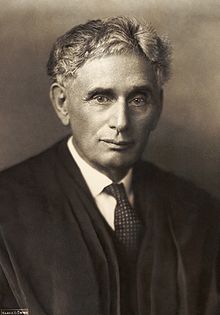

Emerging in the late 2010s,[2] the movement takes inspiration from former US Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, who was known for anti-monopolistic stances.[3][4] Brandeis believed that antitrust action should prevent any one company from maintaining too much power over the economy because monopolies were harmful to innovation, business vitality, and the welfare of workers.[5][6] He labeled high market power concentration as "The Curse of Bigness," believing that large profitable firms use their money to influence politics and create further consolidation and dominance, once stating, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”[6][7]

From World War II until the 1970s, the Brandeisian view that high market concentration leads to anticompetitive behavior was called the Harvard School of thought because the view was primarily associated with Harvard University, including works by economists Edward Mason, Edward Chamberlain, and Joe Bain. In the early late 1970s, this view fell out of favor to be replaced by the Chicago School of thought which advocates that antitrust law should focus on the short term effects of mergers on consumer prices.[6]

The New Brandeis theory was popularized by legal scholar Lina Khan in an article about the negative effects of monopoly power by the company Amazon.[6] The theory would heighten scrutiny of large company mergers.[8] The term "hipster antitrust" originally began as a Twitter hashtag, and rose to prominence when Senator Orrin Hatch used the term during multiple speeches on the United States Senate floor.[9][10][11][12] The movement was perceived to grow in influence during the Biden administration, as compared to the prior Trump and Obama presidencies.[13] The Wall Street Journal described the movement as "a new generation of trustbusters" in 2021, arguing that it represented a shift away from a singular focus on perceived consumer welfare that began with the Reagan administration and the ideas of Robert Bork.[14]

Description[]

The New Brandeis movement suggests that monopoly strength is growing due to the concentration of power between a few big companies.[5] Neo-Brandeisians claim it's problematic that only a few dominant companies determine what political and artistic content are seen by billions of users. They also claim some dominant tech platforms create high barriers for potential competitors and reduce bargaining power of individual merchants, content providers, and app developers.[14] The movement advocates for market structures that prevent anti-competitive practices and would increase scrutiny of vertical mergers between companies that have reached a dominant size in the same supply chain. Proponents believe antitrust laws should focus less on short-term price effects of mergers and more on improving the market conditions necessary to promote real competition.[5][14][15]

Support and opposition[]

Individuals who have been described as being associated with the movement include Lina Khan, Tim Wu, Jonathan Kanter, and Barry Lynn.[13][16][17] Senator Cory Booker has been described as an ally of the movement,[18] and has called on the United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division and Federal Trade Commission to focus their enforcement efforts more on helping workers.[19] Matt Levine of Bloomberg News has written that the term hipster antitrust "appeals to nostalgia for old-fashioned antitrust enforcement".[20] Some proponents of the movement believe the term is pejorative.[21] The term was coined by ,[when?][22] an attorney at Dechert, and popularized by former Federal Trade Commissioner Joshua D. Wright.[23][24] The movement has since been the subject of both academic conferences,[25] research papers,[26] and academic journals.[27]

Critics of the New Brandeis movement believe that promoting competition for its own sake causes inefficient producers to stay in business, preferring a litigation approach based on empirical evidence.[6]

References[]

- ^ "The New Brandeis Ideology (mid 2010s – Present): On the Dangers of Monopoly Power". Unbuilt Labs. 2021-01-06. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ Khan, Lina (2018-03-01). "The New Brandeis Movement: America's Antimonopoly Debate". Journal of European Competition Law & Practice. 9 (3): 131–132. doi:10.1093/jeclap/lpy020. ISSN 2041-7764.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-04-04). "This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ De La Cruz, Peter. "The Antitrust Pendulum Swings to the Populist Pole". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ a b c "What more should antitrust be doing?". The Economist. 2020-08-06. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ a b c d e Eeckhout, Jan (June 2021). The Profit Paradox: How Thriving Firms Threaten the Future of Work. Princeton University Press. pp. 246–248. ISBN 978-0-691-21447-4.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-04-04). "This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Webb, Patterson Belknap; Walter-Warner, Tyler LLP-Jake; Hatch, Jonathan H. (2018-11-08). "A Brief Overview of the "New Brandeis" School of Antitrust Law". Lexology. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ "Hatch Speaks on Growing Controversy Over Antitrust Law in the Tech Sector - Press Releases - United States Senator Orrin Hatch". www.hatch.senate.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-02-08. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Senator Leans Into Avocado Toast Trend to Make a Point". Time. Archived from the original on 2018-03-06. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-08-07). "Orrin Hatch, the Original Antitrust Hipster, Turns on His Own Kind". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 2018-02-22. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Hatch Speaks Again on 'Hipster Antitrust,' Delrahim Confirmation". Orrin Hatch Official site. 2018-02-20. Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ a b Sammon, David Dayen, Alexander (2021-07-21). "The New Brandeis Movement Has Its Moment". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ a b c Ip, Greg (2021-07-07). "Antitrust's New Mission: Preserving Democracy, Not Efficiency". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Khan, Lina M. "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox". www.yalelawjournal.org. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ Nylen, Leah. "Biden launches assault on monopolies". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 2021-07-08. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "The New Brandeis Movement: America's Anti-Monopoly Debate". Open Markets Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "US: 'Hipster Antitrust' ally joins The Senate Judiciary Committee | Competition Policy International". www.competitionpolicyinternational.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Booker calls on antitrust regulators to start paying attention to workers". Vox. Archived from the original on 2018-03-18. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Levine, Matt (2018-09-10). "Keep Your Bitcoins in the Bank". www.bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ "Amazon's Antitrust Antagonist Has a Breakthrough Idea". Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Medvedovsky, Kostya (2017-06-19). "Antitrust hipsterism. Everything old is cool again". @kmedved. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Do Not Mistake Orrin Hatch for #HipsterAntitrust". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Hipster antitrust hits the Senate: The Tipline for 4 August 2017". globalcompetitionreview.com. 2017-08-04. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "George Mason Law Review's 21st Annual Antitrust Symposium – Law & Economics Center". masonlec.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Daly, Angela (2017-08-02). "Beyond 'Hipster Antitrust': A Critical Perspective on the European Commission's Google Decision". SSRN 3012437. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Antitrust Chronicle – Hipster Antitrust | Competition Policy International". www.competitionpolicyinternational.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- Political movements in the United States

- United States law

- United States antitrust law