New Hanseatic League

New Hanseatic League | |

|---|---|

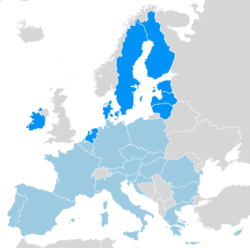

Map of the European Union in light blue with the members of the New Hanseatic League in dark blue | |

| Membership | |

| Establishment | February 2018 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,075,220 km2 (415,140 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 49,510,438[1] |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | $2,499 billion[2] |

The New Hanseatic League, or the Hansa,[3] was established in February 2018 by European Union finance ministers from Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden through the signing of a two-page foundational document[4] which set out the "shared views and values in the discussion on the architecture of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union (EMU)." The name is derived from the Hanseatic League, a Northern European commercial and defensive league which lasted until the 16th century.

The New Hanseatic League developed from an informal cooperation among like-minded fiscally conservative northern European states that has also been referred to at various points as 'The Vikings' and the 'Bad Weather coalition'.[citation needed] The grouping sees clubbing together as a way to make up for the loss of the like-minded United Kingdom in the European political arena after Brexit.[5][6] The countries involved want a more developed European single market, particularly in the services sector (i.e. a so-called 'Capital Markets Union').[5][6] They also want to develop the European Stability Mechanism into a full European Monetary Fund that would redistribute wealth from trade surplus to trade deficit EU member states.[7] A number of think tanks – including Free Trade Europa - support this policy approach[8]

In a speech delivered in the Netherlands, Ireland's Tánaiste (deputy head of government) Simon Coveney suggested cooperation among the countries in the alliance could extend to foreign policy as well, such as the Middle East peace process and the EU's relations with Africa.[9] Some have expressed fears the New Hanseatic League could exacerbate existing north–south political divides in Europe by grouping northern European countries too closely.[7] A more recent fiscally conservative group of EU nations exists in an informal setting, dubbed the Frugal Four. It consists of some of the New Hanseatic League member states plus Austria.

In November 2018, the New Hanseatic group called for the European Stability Mechanism to be given a greater role in scrutinising state budgets. Under the plan, formal tests of a state government's debt sustainability and ability to repay would be carried out before aid could be provided. The call came after the European Commission's rejection of Italy's 2019 budget, and was signed by all eight members of the League, along with two additional signatures from Czechia and Slovakia.[10][11]

See also[]

- Baltic Assembly

- Benelux

- Craiova Group

- EU Med Group

- Frugal Four

- Hanseatic League

- Oslo Agreements, 1930

- Three Seas Initiative

- Visegrád Group

References[]

- ^ "Council Decision of 12 December 2017". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ "World Bank, International Comparison Program database". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ "Subscribe to read | Financial Times". www.ft.com. Cite uses generic title (help)

- ^ "Finance ministers from Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden underline their shared views and values in the discussion on the architecture of the EMU" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The EU's new Hanseatic League picks its next Brussels battle". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "EU's New Hanseatic League picks its next battle". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Why a New Hanseatic League will not be enough". The Clingendael Spectator. 2018-09-25. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "FREE TRADE EUROPA LANSERAR SIN EU-MANIFEST "OUR EUROPE. OUR FUTURE"". Via TT. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Speech by Tánaiste Simon Coveney T.D. at The Hague, The Netherlands". Irish Department of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Hawkish European capitals lobby to beef up eurozone bailout fund". Financial Times. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "The euro 'hawks' want bigger say for crisis fund in cuts and reforms". EURACTIV.com. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Hanseatic League

- European Union

- Foreign relations of Denmark

- Foreign relations of Estonia

- Foreign relations of Finland

- Foreign relations of Ireland

- Foreign relations of Latvia

- Foreign relations of Lithuania

- Foreign relations of the Netherlands

- Foreign relations of Sweden

- International organizations based in Europe

- Bottom-up regional groups within the European Union