Nick Carraway

| Nick Carraway | |

|---|---|

| The Great Gatsby character | |

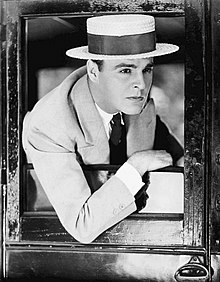

Nick Carraway as portrayed by actor Neil Hamilton in The Great Gatsby (1926) | |

| Created by | F. Scott Fitzgerald |

| Portrayed by | See list |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Bond salesman |

| Family | Daisy Buchanan (cousin) |

| Nationality | American |

Nick Carraway is a fictional character and narrator in F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby.

Character biography[]

In his narration, Nick Carraway explains that he was born in the Middle West. The Carraway family owned a hardware business (opened in 1851) and were something of an established family. Nick served in World War I in the Third Division, or Third Infantry Division. At a young age his father advised him to reserve all judgements on people. After the war he moved from the Midwest to West Egg, a wealthy enclave of Long Island, to learn about the bond business. He takes up residence near his cousin, Daisy Buchanan and her affluent husband Tom, who was Nick's classmate at Yale University. They introduce him to their friend Jordan Baker, a cynical young heiress and golf champion. She and Nick begin a brief romance.

Another neighbor and Daisy Buchanan's former lover, Jay Gatsby, invites Nick to one of his legendary parties. Nick is immediately intrigued by the mysterious socialite, especially when Gatsby introduces him to the gangster Meyer Wolfsheim, who is rumored to have helped Gatsby make his fortune in the bootlegging business. Gatsby takes a liking to Nick, and confesses to him that he has been in love with Daisy since before the war and that his extravagant lifestyle is just an attempt to impress her. He asks Nick for his help in winning her over. Nick invites Daisy over to his house without telling her that Gatsby will be there. When Gatsby and Daisy resume their love affair, Nick serves as their confidant.

Nick later discovers that Daisy struck and killed George's wife (and Tom's lover), Myrtle Wilson, in Gatsby's car. Tom then tells George that Gatsby had been driving the car. George then kills Gatsby and then himself. Nick holds a funeral for Gatsby, breaks up with Jordan, and decides to leave West Egg and return to his native Midwest, reflecting that the era of dreaming which Gatsby represented is over.[1]

Analysis[]

Ian Armstrong believes that "In the character of Nick, Fitzgerald has written an idealized version of someone he wanted to be,"[2] but Carraway is not Fitzgerald. As the narrator of the story, Carraway recounts events occurring two years previously. The other characters are presented as Carraway perceives them, and thus directs the reader's sympathies. He is selective in what information he chooses to disclose. Fitzgerald wrote, "in Gatsby I selected the stuff to fit a given mood of 'hauntedness' or whatever you might call it, rejecting in advance in Gatsby, for instance, all the ordinary material of Long Island".[3] Carraway's status as at first an observer, then a participant, gives rise to questions regarding his reliability as narrator. He says little about a rumored previous engagement, or his wartime experience; both of which are first raised by other characters.

Carraway describes his attraction to Jordan Baker as "I wasn't actually in love, but I felt a sort of tender curiosity."[4]

Queer reading[]

Fitzgerald scholars and fans of The Great Gatsby frequently interpret Nick Carraway as being gay or bisexual.[5] Many queer interpretations of Nick’s character hinge on a scene at the end of Chapter 2, in which an elevator lever is used as a phallic symbol. There are then ellipses followed by a brief scene in which Mr. McKee, described earlier as a “pale, feminine man,” is “sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands.” Frances Kerr points to the phallic symbolism and the unaccounted-for time in this scene as evidence of The Great Gatsby’s “bizarre homoerotic leitmotif.”[6] Additionally, Edward Wasiolek argues that this scene is evidence of Nick’s “homosexual proclivities,” and he claims that “I do not know how one can read the scene in McKee's bedroom in any other way, especially when so many other facts about his behavior support such a conclusion.”[7]

Additional indications of Nick Carraway’s possible homosexuality stem from a comparison of his descriptions of men and women within the novel. For example, the greatest compliment that Nick gives Daisy is that she has a nice voice, and his description of Jordan sounds much like a description of a man. Conversely, Nick’s description of Tom focuses on his muscles and the “enormous power” of his body, and in the passage where Nick first encounters Gatsby, Greg Olear argues that “if you came across that passage out of context, you would probably conclude it was from a romance novel. If that scene were a cartoon, Cupid would shoot an arrow, music would swell, and Nick’s eyes would turn into giant hearts.”[8] Joseph Vogel also points to this passage in arguing in favor of a queer reading of Nick, contrasting the intensity of his relationship with Gatsby to the way Daisy and Jordan “alternately charm and disturb Nick.”[9] Near the end of the novel, Tom also says of Gatsby, “that fellow had it coming to him. He threw dust in your eyes just like he did in Daisy’s,” demonstrating Nick’s attraction to Gatsby and how this attraction prevents him from forming a critical judgment of him.

Different authors draw different conclusions regarding the importance of Nick’s sexuality to the novel - Olear argues that Nick idealizes Gatsby in a similar way to how Gatsby idealizes Daisy, Noah Berlatsky sees Nick’s sexuality as emphasizing both Jordan and Gatsby’s dishonesty,[10] and Tracy Fessenden claims that Nick’s attraction to Gatsby serves to contrast the love story between Gatsby and Daisy.[11] Indeed, as Joseph Vogel puts, it “a strong case can be made that the most compelling story of unrequited love—in both the novel and the film—is not between Jay Gatsby and Daisy, but between Nick and Jay Gatsby.”

Michael Bourne says whether or not Carraway is gay "...can’t be proven one way or the other—but I suspect the queer readings of Nick Carraway say more about the way we read now than they do about Nick or The Great Gatsby."[12] Steve Erickson, writing in LA Magazine, says that Carraway's fascination with Gatsby is less of his being in love with Gatsby than "...Carraway, back from the war and back from the Midwest and wanting nothing more than to be Gatsby himself".[13] Matthew J. Bolton says, "to conclude that the incident with Mr. McKee establishes Nick's homosexuality would probably be a case of what narratologists call "overreading."[3]

Portrayals[]

Film[]

- Neil Hamilton portrays Carraway in the 1926 film The Great Gatsby.

- Macdonald Carey portrays Carraway in the 1949 film The Great Gatsby.

- Sam Waterston portrays Carraway in the 1974 film The Great Gatsby.

- Tobey Maguire portrays Carraway in the 2013 film The Great Gatsby.[14]

Television[]

- Lee Bowman portrays Carraway in the 1955 television adaptation.

- Rod Taylor portrays Carraway in the 1958 television adaptation.

- Paul Rudd portrays Carraway in the 2000 television adaptation.

Radio[]

- In October 2008, the BBC World Service commissioned and broadcast an abridged 10-part reading of the story, read from the view of Nick Carraway by Trevor White.[15]

- Bryan Dick played Carraway in the 2012 two-part BBC Radio 4 Classic Serial production.[16]

In 2021 Michael Farris Smith's novel Nick was released, described as a sort of "prequel" to Gatsby.

See also[]

- Nick (novel), a prequel to The Great Gatsby centering on Nick Carraway

References[]

- ^ Love for Love. Love for Love. 1999-01-29. doi:10.5040/9781408164501.00000015. ISBN 9781408164501.

- ^ Armstrong, Ian. "The Voice of Fitzgerald", Bad & baggage Productions

- ^ a b Bolton, Matthew J., "A Fragment of Lost Words":Narrative Ellipses in The Great Gatsby", Critical Insights p. 193

- ^ "Characters", BBC

- ^ Herman, Daniel (July 28, 2017). "The Great Gatsby's Nick Carraway: His Narration and His Sexuality". Anq: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. ANQ, A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes, and Reviews. 30 (4): 247–250. doi:10.1080/0895769X.2017.1343656. S2CID 164965464. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Kerr, Frances (June 1996). "Feeling "Half Feminine": Modernism and the Politics of Emotion in The Great Gatsby". American Literature. 68 (2): 405–431. doi:10.2307/2928304. JSTOR 2928304. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Sexual Drama of Nick and Gatsby". International Fiction Review. 1992. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Olear, Greg (January 9, 2013). "Nick Carraway is gay and in love with Gatsby". Salon. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Vogel, Joseph (2015). ""Civilization's Going to Pieces": The Great Gatsby, Identity, and Race, From the Jazz Age to the Obama Era". The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. Penn State University Press. 13 (1): 29–54. doi:10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.13.1.0029. JSTOR 10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.13.1.0029. S2CID 170386299. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ Berlatsky, Noah (May 13, 2013). "The Great Gatsby Movie Needed to Be More Gay". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Fessenden, Tracy (2005). "F. Scott Fitzgerald's Catholic Closet". U.S. Catholic Historian. Catholic University of America Press. 23 (3): 19–40. JSTOR 25154963. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ Bourne, Michael. "The Queering of Nick Carraway", The Millions, April 23, 2018

- ^ Erickson, Steve. "In a New Prequel to ‘The Great Gatsby,’ Nick Carraway Gets His Own Mystery", LA Magazine, January 4, 2021

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (May 6, 2013). "A Very Thoughtful Tobey Maguire on The Great Gatsby, Mental Health, and On-Set Injuries". vulture.com. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ "BBC World Service programmes – The Great Gatsby". Bbc.co.uk. 2007-12-10. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "F Scott Fitzgerald - The Great Gatsby, F Scott Fitzgerald - The Great Gatsby, Classic Serial - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Characters in American novels of the 20th century

- Drama film characters

- Fictional characters from Minnesota

- Fictional characters from New York (state)

- Fictional people in finance

- Fictional World War I veterans

- Fictional writers

- Fictional Yale University people

- Literary characters introduced in 1925

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in film

- The Great Gatsby