Nim Chimpsky

Nim Chimpsky (November 19, 1973 – March 10, 2000) was a chimpanzee and the subject of an extended study of animal language acquisition at Columbia University. The project was led by Herbert S. Terrace with the linguistic analysis headed up by psycholinguist Thomas Bever. Within the context of a scientific study, Chimpsky was named as a pun on linguist Noam Chomsky, who posits that humans are "wired" to develop language.[1] Though usually called Nim Chimpsky, his full name was Neam Chimpsky, or Nim for short.[2]

As part of a study intended to challenge Chomsky's thesis that only humans have language,[3] beginning at two weeks old, Nim was raised by a family in a home environment by human surrogate parents.[2] The surrogate parents already had a human child of their own.[4] At the age of two Nim was removed from his surrogate parents, the familiar surrounding of their home and brought to Columbia university due to perceived behavioral difficulties.[5] The project was similar to an earlier study by R. Allen and Beatrix Gardner in which another chimpanzee, Washoe, was raised like a human child.[6] After reviewing the results, Terrace concluded that Nim, who at this point was housed at Columbia University, mimicked symbols of the American Sign Language from his teachers in order to get a reward but did not understand the language nor could he create sentences; Nim used random patterns until receiving a reward. Mainly, Terrace claimed that he had noticed that Nim mimicked the signs used moments before by his teacher, which Terrace, by his own words, had not noticed throughout the duration of the entire study but only moments before thinking of greenlighting the study as a success.[7][8][2] Terrace further argued that all ape-language studies, including Project Nim, were based on misinformation from the chimps, which he also only noticed and examined in such a manner at and after said moment of realization.[9] Terrace's work remains controversial today, with no clear consensus among psychologists and cognitive scientists regarding the extent to which great apes can learn language.[citation needed]

Project Nim[]

Project Nim was an attempt to go further than Project Washoe. Terrace and his colleagues aimed to use more thorough experimental techniques, and the intellectual discipline of the experimental analysis of behavior, so that the linguistic abilities of the apes could be put on a more secure footing.

Roger Fouts wrote:

Since 98.7% of the DNA in humans and chimps is identical, some scientists (but not Noam Chomsky) believed that a chimp raised in a human family, and using American Sign Language (ASL), would shed light on the way language is acquired and used by humans. Project Nim, headed by behavioral psychologist Herbert Terrace at Columbia University, was conceived in the early 1970s as a challenge to Chomsky's thesis that only humans have language.[3]

Attention was particularly focused on Nim's ability to make different responses to different sequences of signs and to emit different sequences in order to communicate different meanings. However, the results, according to Fouts, were not as impressive as had been reported from the Washoe project. Terrace, however, was skeptical of Project Washoe and, according to the critics,[who?] went to great lengths to discredit it.

While Nim did learn 125 signs, Terrace concluded that he had not acquired anything the researchers were prepared to designate worthy of the name "language" (as defined by Noam Chomsky) although he had learned to repeat his trainers' signs in appropriate contexts.[2] Language is defined as a "doubly articulated" system, in which signs are formed for objects and states and then combined syntactically, in ways that determine how their meanings will be understood. For example, "man bites dog" and "dog bites man" use the same set of words but because of their ordering will be understood by speakers of English as denoting very different meanings.

One of Terrace's colleagues, Laura-Ann Petitto, estimated that with more standard criteria, Nim's true vocabulary count was closer to 25 than 125. However, other students who cared for Nim longer than Petitto disagreed with her and with the way that Terrace conducted his experiment. Critics[who?] assert that Terrace used his analysis to destroy the movement of ape-language research. Terrace argued that none of the chimps were using language, because they could learn signs but could not form them syntactically as language.

Terrace and his colleagues[who?] concluded that the chimpanzee did not show any meaningful sequential behavior that rivaled human grammar. Nim's use of language was strictly pragmatic, as a means of obtaining an outcome, unlike a human child's, which can serve to generate or express meanings, thoughts or ideas. There was nothing Nim could be taught that could not equally well be taught to a pigeon using the principles of operant conditioning. The researchers[who?] therefore questioned claims made on behalf of Washoe, and argued that the apparently impressive results may have amounted to nothing more than a "Clever Hans" effect, not to mention a relatively informal experimental approach.

Critics of primate linguistic studies include Thomas Sebeok, American semiotician and investigator of nonhuman communication systems, who wrote:

In my opinion, the alleged language experiments with apes divide into three groups: one, outright fraud; two, self-deception; three, those conducted by Terrace. The largest class by far is the middle one.[10]

Sebeok also made pointed comparisons of Washoe with Clever Hans. Some evolutionary psychologists[who?], in effect agreeing with Chomsky, argue that the apparent impossibility of teaching language to animals is indicative that the ability to use language is an innately human development.[11]

Project Nim, a documentary film by James Marsh about the Nim study, explores the story (and the wealth of archival footage) to consider ethical issues, the emotional experiences of the trainers and the chimpanzee, and the deeper issues the experiment raised. This documentary (produced by BBC Films, Red Box Films, and Passion Films) opened the 2011 Sundance Film Festival.[12] The film was released in theaters on July 8, 2011 by Roadside Attractions,[13] and was released on DVD on 7 February 2012.[14]

Objections[]

Terrace's skeptical approach to the claims that chimpanzees could learn and understand sign language led to heated disputes with and Beatrix Gardner, who initiated the Washoe Project. The Gardners argued that Terrace's approach to training, and the use of many different assistants, did not harness the chimpanzee's full cognitive and linguistic resources.

Roger Fouts, of the Washoe Project, also claims that Project Nim was poorly conducted because it did not use strong enough methodology to avoid comparison to "Clever Hans" and efficiently defend against it. He also shares the Gardners' view that the process of acquiring language skills through natural social interactions gives substantially better results than behavioral conditioning. Fouts argues, based on his own experiments, that pure conditioning can lead to the use of language as a method mainly of getting rewards rather than of raising communication abilities. Fouts later reported, however, that a community of ASL-speaking chimpanzees (including Washoe herself) was spontaneously using this language as a part of their internal communication system. They have even directly taught ASL signs to their children (Loulis) without human help or intervention. This means not only that can they use the language but that it has become a significant part of their lives.[15]

The controversy is still not fully resolved, in part because the financial and other costs of carrying out language-training experiments with apes make replication studies difficult to mount. The definitions of both "language" and "imitation" as well as the question of how language-like Nim's performance was has remained controversial.

Retirement and death[]

When Terrace ended the experiment, Nim was transferred back to the Institute for Primate Studies in Oklahoma, where he struggled to adapt after being treated like a human child for the first decade of his life. He had also never previously met another chimp and had to get used to them.

When Terrace made his one and only visit to see Nim after a year at the Institute of Primate Studies, Nim sprung to Terrace immediately after seeing him, visibly shaking with excitement. Nim also showed the progress he had made during Project Nim, as he immediately began conversing in sign language with Terrace. Nim retreated back to a depressed state after Terrace left, never to return to see Nim again. Nim developed friendships with several of the workers at the Institute of Primate Studies, and learned a few more signs, including a sign named "stone smoke time now" which indicated that Nim wanted to smoke marijuana.[16]

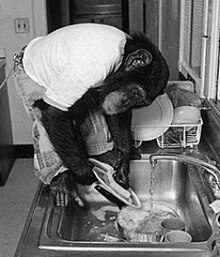

The Institute later sold Nim to the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates (LEMSIP), a pharmaceutical animal testing laboratory managed by NYU. At LEMSIP, Nim was confined to a wire cage, slated to be used for hepatitis vaccine studies.[17] Technicians caring for the chimps noted that Nim and other chimps from the Institute continued to make sign-language gestures. After efforts to free him, Nim was purchased by the Black Beauty Ranch, operated by The Fund for Animals, the group led by Cleveland Amory, in Texas. While Nim's quality of life improved at the Black Beauty Ranch, Nim lived primarily in isolation inside a pen. He began to show hostility that included throwing TVs and killing a dog.[18] Nim's behavior and overall well-being improved when other chimpanzees, several from the LEMSIP, joined Nim inside his pen after about a decade at the Black Beauty Ranch. Nim continued to show signs of the sign language he learned decades ago whenever a former trainer at the Institute for Primate Studies went to visit him.

Nim died on 10 March 2000 at the age of 26, from a heart attack. The story of Nim and other language-learning animals is told in Eugene Linden's book Silent Partners: The Legacy of the Ape Language Experiments.[19]

Quotations[]

All quotations appear in the original article by Terrace and colleagues.[2]

- Three-sign quotations

- Apple me eat

- Banana Nim eat

- Banana me eat

- Drink me Nim

- Eat Nim eat

- Eat Nim me

- Eat me Nim

- Eat me eat

- Finish hug Nim

- Give me eat

- Grape eat Nim

- Hug me Nim

- Me Nim eat

- Me more eat

- More eat Nim

- Nut Nim nut

- Play me Nim

- Tickle me Nim

- Tickle me eat

- Yogurt Nim eat

- Four-sign quotations

- Banana Nim banana Nim

- Banana eat me Nim

- Banana me Nim me

- Banana me eat banana

- Drink Nim drink Nim

- Drink eat drink eat

- Drink eat me Nim

- Eat Nim eat Nim

- Eat drink eat drink

- Eat grape eat Nim

- Eat me Nim drink

- Grape eat Nim eat

- Grape eat me Nim

- Me Nim eat me

- Me eat drink more

- Me eat me eat

- Me gum me gum

- Nim eat Nim eat

- Play me Nim play

- Tickle me Nim play

- Longest recorded quotation

Nim's longest "sentence" was the 16-word-long "Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you."[20]

Further reading[]

- Hess, E. (2008). Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human. New York: Bantam. ISBN 9780553803839.

- Seidenberg, M. S.; Pettito, L.A. (1979). "Signing behavior in apes: A critical review". Cognition. 7. pp. 177–215.

- Terrace, H. S. (1979). Nim. New York: Knopf.

- Terrace, H. S.; Singer, P. (November 24, 2011). "Can Chimps Converse?: An Exchange". New York Review of Books.

See also[]

- Chantek

- Kanzi

- Koko

- Lucy

- Panbanisha

- Jennie, a fictional novel about a chimpanzee living with a family in the 1970s learning sign language

References[]

- ^ Radick, Gregory (2007). The Simian Tongue: The Long Debate about Animal Language. University of Chicago Press. p. 320.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Terrace, Herbert; Petitto, L. A.; Sanders, R. J.; Bever, T. G. (November 23, 1979). "Can an ape create a sentence" (PDF). Science. 206 (4421): 891–902. Bibcode:1979Sci...206..891T. doi:10.1126/science.504995. PMID 504995. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

However objective analysis of our data, as well as those obtained by other studies, yielded no evidence of an ape's ability to use a grammar.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A chimp named Nim". Independent Reader. Archived from the original on 2008-04-13. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "The Chimp That Learned Sign Language".

- ^ "The Chimp That Learned Sign Language".

- ^ Berger, Joseph (July 3, 2011). "Chasing a Namer lost to Time". The New York Times.

- ^ Terrace, Herbert. "Project Nim — The Untold Story" (PDF). appstate.edu.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2007–2008). "On the Myth of Ape Language" (e-mail correspondence). Interviewed by Matt Aames Cucchiaro. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via chomsky.info.

- ^ Terrace, Herbert S. (2019). Why Chimpanzees Can't Learn Language and Only Humans Can. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Wade, N. (1980). "Does man alone have language? Apes reply in riddles, and a horse says neigh". Science. 208. pp. 1349–1351.

- ^ Pinker, S.; Bloom, P. (1990). "Natural language and natural selection". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 13. pp. 707–784.

- ^ "Project Nim". sundance.bside.com. Sundance Film Festival. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 27, 2011). "Sundance: Roadside Attractions To Release 'Project Nim'". Deadline.com. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Project Nim". Metacritic.com.

- ^ Fouts, Roger; Mills, Stephen Tukel (1998). Next of Kin: My Conversations with Chimpanzees. William Morrow Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0380728220.

- ^ "'Project Nim': A Chimp's Very Human, Very Sad Life". NPR.org. NPR. July 20, 2011.

- ^ Hess 2008, ch. 11

- ^ Hess 2008, p. 296.

- ^ Linden, Eugene (1987). Silent Partners: The Legacy of the Ape Language Experiments. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345342348.

- ^ Terrace, H. S. (1979). "How Nim Chimpsky Changed My Mind". Ziff-Davis Publishing Company.

External links[]

- "'Test' results". ling.ohio-state.edu. Archived from the original on 2003-06-25.

- "Official website for Project Nim documentary". project-nim.com. Archived from the original on 2011-01-20.

- Apes from language studies

- 1973 animal births

- 2000 animal deaths

- Individual chimpanzees

- Noam Chomsky