Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company

| |

| Locale | Washington, DC Norfolk, VA |

|---|---|

| Waterway | Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay |

| Transit type | Freight and Passenger Ferry |

| Operator | Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company |

| Began operation | January 4, 1890 |

| Ended operation | November 26, 1948 |

| System length | 195.7 miles (314.9 km)[1] |

| No. of vessels | 8 |

| No. of terminals | 6 |

The Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company was a steamboat company that transported passengers and freight between Washington, DC and Norfolk, Virginia on the Potomac River.

History[]

The company was organized in the Spring of 1889[2] and charter in 1890 with the capital largely coming from Washingtonians.[3] A bill was introduced on January 4, 1890 for incorporation in the Virginia State Senate. The object of the company was to equip and operate a line of steamers for the transport of passengers and freight between Washington, DC and Norfolk, Virginia on the Potomac River. The capital stock was to be no less than $100,000 and an option for a railroad to be built inland was introduced. The Company was to build four first-class powerful steamers with all modern improvements according to the incorporation bill. They would run from Washington, DC to Norfolk with stops in Alexandria at Old Point and Newport News.[4] The original Commissioners were Chas. C. Duncanson, John Callahan and Levi Woodbury.[5]

Early years (1890–1900)[]

In 1890, the company started operating with a sidewheeler named the George Leary. It operated from Washington to Norfolk with stops in Alexandria and Old Point Comfort.[3] Two additional boats were specially ordered to run the line at night. Two other boats were to be built if the business need arose to have day trips.[6] These boats would be known as the Washington and the Norfolk.

The Washington[]

Its first steamer of the fleet that was to be nicknamed the Potomac Palaces was the Washington. It named after one of the ports being serviced by the company and was launched on November 22, 1890 in Wilmington, Delaware. Manufactured by Harlan and Hollingsworth, it was launched at 9 am on that day in the presence of several members of the company who had traveled to the city for the occasion.[7] It was christened by Miss Jane McCoy, aged 12 years old and daughter of Dr. McCoy of Philadelphia. It measured 258 feet in length with a width of 46 feet and a depth of 23 feet. It was made of iron and double-plated from the front to mid-ship at the waterline to allow it to cut through the ice that could form in the area. Six bulk heads divided the ship and offered additional protection in case of a leak occurring in a compartment. It was driven by a screw propeller of 13 1/2 in diameter with triple expansion engines of 2,000 horse power and 14 feet boilers guaranteeing a speed of 17 miles per hour.[2]

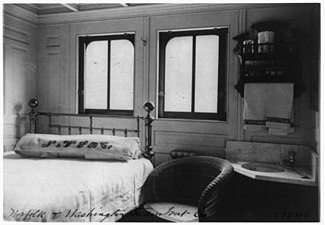

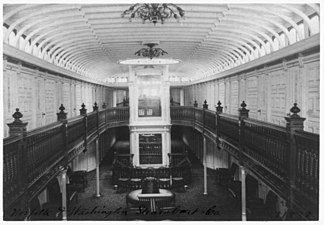

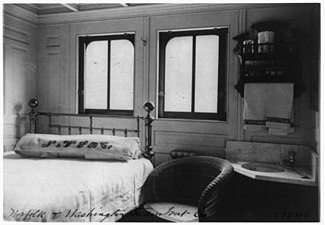

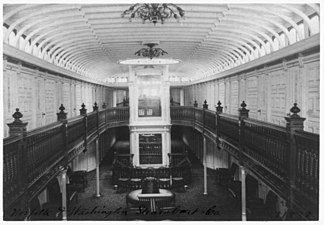

The saloon deck extended the entire length of the ship. It had forty bedrooms and eight double state-rooms. The interior was decorated and paneled and the main colors were white and gold. The Officer's quarters had a gallery containing twelve bedrooms with an inside stairway connecting it to the saloon. The staterooms and the main stairways were finished in quartered oak while the dining room was made of maple and could accommodate 60 people. The kitchen with its pantry and refrigeration and steward's room were equipped with the latest standard in appliances at the time. The main deck had 22 staterooms, a social hall, a barbershop, bathroom, a purser's office and a baggage room decorated in paneling terra-cotta, butternut and gold. The entire ship was lighted with electricity.[2]

A trial trip was conducted on March 12, 1891 on the Delaware River and Bay from Christian's Creek to Ledge Light and back, a distance of eighty miles. Guests including the commissioners, were on board to witness the trial and were served a luncheon by the builders. A speed test was conducted during the run resulting in the boat making a mile in three minutes and seven seconds.[8] The steamer arrived at the DC wharf on March 26, 1891 under the command of Captain S. B. Davis who had been navigating the Potomac since 1871.[9]

On September 29, 1890, it was recommended by Captain Rossell that a lease be approved for a wharf located next to the arsenal wall. The steamboat company had made a request a few days earlier to have a landing point in the city. The recommendation called for an annual rent of $2,500 with an allowance of $1,500 for keeping the wharf in working order. It was approved by the Commissioners.[10]

The Norfolk[]

The second steamer of the fleet was named the Norfolk after the second port being serviced by the company and was launched on January 10, 1891 at 12:25 in Wilmington and also manufactured by Harlan and Hollingsworth as its sister ship. It was christened by Bessie Callahan, the 18-year-old of John Callahan, one of the company's commissioner. It was built to exactly the same specification as its twin-sister, the Washington.[11]

The Washington and the Norfolk were the only ones in Washington, DC able to navigate the Potomac when ice formed. Due to their design, they were able to crush the ice under their weight and make a channel to navigate. On February 7, 1895, while the rest of the boats had to remain docked, the steamboats were able to make the trips on time. Ice was reported to be heavy all the way to Piney Point and fields off Point Lookout.[12]

The line operated with two boats from 1891 to 1894. On September 13, 1894, the Alexandria Gazette reported that the Mayor of Alexandria, Henry Strauss, addressed a letter to the company informing them that its steamers were damaging the wharves as well as the small crafts docked there. They were going too fast as they passed the city as well as when they docked. Superintendent Callahan promptly acknowledged the concern and replied that he had ordered the captains to be careful and make sure no damages were done.[13] This prompt response was probably warranted by the upcoming announcement done only two days later.

On September 15, 1894, after months of speculation, it was announced by Superintendent John Callahan, that a third steamer was to be built. The route had been a success for the company and the traffic warranted a new addition to the line. It would operate during the day and be larger and more powerful than the other two steamers while retaining their comfort.[14] The contract was awarded to the Newport News Shipbuilding Company on November 15, 1894.[15] The steamer would operate the day trip during the summers leaving Washington, DC at 8:30 am and arriving in Norfolk at 6:30 pm. It would be touching Alexandria, Piney Point, Point Lookout and Old Point.[16] In the winters, she would relieve the other two ships o the company during their annual docking and overhauling[17]

On March 9, 1895, the District Commissioners granted a revocable permit to the Company. This permit allowed them to dredge a slip 56 feet wide, support the sides with piles to make it a steamboat berth. It was not to extend beyond he west building line of Water Street SW nor beyond the harbor line. The permit could be revoked with a 60-day notice to the company.[18]

The Newport News[]

On April 9, 1895, the Newport News is launched from the city for which it is a namesake.[19] The trial trip took place on June 6, 1895 under the command of Captain Georghegan between Old Point Light and Windmill Point Light, a distance of 46 miles and back. The average speed was 19 miles with a maximum of 21 miles. The test was considered a success.[20] On June 18, 1895 it was formally turned over to its owners.[21] A formal ceremony took place. The same day, it made the trip upriver to Washington leaving Norfolk at 6:30 pm on rough waters and arriving in Washington at 6:00 am. The public was invited to visit the ship on Sunday, June 23, 1895. It would take over for a few days the evening trip while the other ships were overhauled until July 1. Starting on July 4, 1895, the 1,500-ton ship would provide run the day trip.[22]

The interior was furnished with heavy oak furniture richly upholstered in brown corduroy with Louis XVI design. The interior woodwork was enameled white, picked out in gold in artistic mermaid designs and panelings.[22]

Interior view of one of the cabins

Interior view of steamboat showing stairway and pursers office

Interior view of galleried central parlor with clerestory

20th Century (1900–1948)[]

In 1907, the company experience the best year during the Jackson Exposition in Norfolk. A modern, all-steel day boat was built for the occasion. It was a sidewheeler called the Jamestown and ran the entire summer. It ran again in 1908 but the success was not there. The boat was sold to an Argentine firm.[3]

On October 3, 1908 at 1 o'clock in the afternoon, in the Newport News Shipbuilding Company yard, the Southland is launched in front of a crowd of hundreds.[23] In 1909, the new steamer is delivered, followed in 1911 with its sister ship, the Northland. These boats had steel hulls unlike its predecessors who were made of charcoal iron.[3]

The Norfolk and the Washington were sold to the Colonial Line where they were renamed the Lexington and Concord. They operated the line between New York and Providence until World War I.[3]

1918 Fire[]

1918 was a catastrophic year for the company. On the morning of September 3, 1918, C.B. Abbott, watchman and night clerk for the Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company was sitting in the office. Around 3:30 am, he smelled smoke and went to the back of the building to investigate. He discovered smoke in the linen room and ran out the building. There flames were shooting up the side of the building. He pulled the alarm and yelled at the watchman on the boat that there was a fire. Within a few minutes, the fire had spread to three or four rooms. Five minutes later, the Newport News as on fire from flames of the warehouse. Explosions were heard on the steamer due to cans of paint in the hold bursting. A consignment of several hundred two-quart and one-gallon tins were on the ship. The fire department was unable to save the boat. A second alarm was turned on within ten minutes as the fire was spreading quickly. By 4 am, four alarms had sounded.[24]

A scow belonging to Portch & Jones, dock builders and pile drivers, was moored to the wharf which was also on fire. Emmett I. Portch, head of the company, climbed over a wooden fence between the street and the river before jumping in a small boat in an attempt to row to the scow to save it. He took a butter barrel sitting on the dock and started throwing water at the fire while trying to untie the scow to move it from the dock. At that very moment, he was hit in the chest by a stream of water from a fire hose, knocking him 20 feet in the water. He was saved by two soldiers standing on another dock who had jumped in a boat to fish him out. He jumped back to the scow and managed to move it way.[24]

The fire destroyed $75,000 worth of freight stored in the warehouse and on the steamboat. Among the goods damaged on the steamer were several chasses, two automobiles, two airplane engines, the chassis of an automobile truck, several bed springs and mattresses, thousands of bottles of soda water, 100 sacks of peanuts, fourteen barrels of tar, two marine engines, the chassis of an automobile steam boilers and several tanks of carbonated water.[24]

The wharves and office were destroyed which was valued at $25,000. The superstructure of the steamer was damaged to the extent of $100,000. The hull, engine and machinery were unharmed. The passenger service to Norfolk was not interrupted as the company had other steamers. The old Jamestown dock and adjoining offices would be used during the reconstruction.[24]

It was rebuilt and renamed the Midland. Two years later, another fire started in the wharf. The steamboat was saved by pulling her out of the channel. She burned again in 1924 and was sold to the Colonial Line. It remained moored near Alexandria for a few years before finally being scrapped.[3]

The Northland

The Southland

The Newport News (later renamed the Midland)

The District of Columbia, the last steamboat[]

In 1924, a new boat is built and delivered to replace the Midland. It is called the District of Columbia. Built in Wilmington by Pusey & Jones Company, it was christened on September 12, 1924 by Miss Margaret Callahan, daughter of Daniel J. Callahan, the vice president and general manager at the time. 12 seconds later, the boat was in the water. The new steamboat was outfitted with more rooms with private bathrooms, staterooms with private toilets and showers, running hot water as well as cold water in all staterooms lavatories, mechanical ventilation of the dining saloon as well as the staterooms. It was decorated with luxurious furniture and able to carry approximately 600 passengers. It was powered with a single screw and made of steel. It was 305 feet 6 inches long, an extreme beam of 52 feet, a molded depth of 18 feet and a dept of floor of the pilot house of 42 feet.[25]

Incidents on board[]

In the night of January 7, 1935 at 10:50 pm, the District of Columbia ran aground near Five-Point Lighthouse, 7 miles from Colonial Beach, VA, 60 miles down the Potomac. Captain Posey was in command and had been on the Potomac since the 1890s. The poor visibility due to fog was blamed for the incident with 75 passengers on board and 29 automobiles. The passengers were removed from the boat by the ferry-boat, Lord Baltimore on the following day at 10:15 am and taken to Morgantown, MD. From there, they were taken to Potomac Beach were they were loaded on buses to Norfolk. In the afternoon, a Government tug-boat was attempting to pull the boat out but with no success. High tide was expected to pull it out.[26]

On April 13, 1941, a scuffle occurred on board the Northland between Raymond F. Reutt, 24, a former football player and wrestler star of the Virginia Military Institute living of Norfolk and the First Officer, Harry B. Murphy. Murphy was thrown over board from the hurricane deck by Reutt and disappeared. The Northland stayed on site for two hours looking for Murphy but was unsuccessful in finding his body. The search for his body continued for several days. Reutt was arrested in Norfolk upon arrival. Since the incident took place in Charles County, Maryland, it was determined that Maryland had jurisdiction. He was arraigned on charges of manslaughter with his bail set at $2,500 pending extradition proceedings to Maryland.[27]

According to Captain Hewett's statement, he was told by the saloon watchman that three men were bothering other passengers and that Mr. Reutt was one of the men. He had posted a watchman in front of his room but found that the man along with another passenger had climbed on the top deck. Mr. Murphy arrived on the deck a few minutes later and took his right arm to encourage him to go back to his room as he was afraid he might fall overboard. The Captain grabbed the other arm. The defendant snatched his arm away from the Captain and whirled around toward the First Officer. The First Officer went overboard as the deck did not have a railing.[28] The body of Harry B. Murphy was found on April 30, 1941 near where he had fallen and was found by another Captain operating between Morgantown and Colonial Beach.[29] Raymond F. Reutt was acquitted on November 26, 1941 by a Jury in La Platte, MD.[30] On March 26, 1942, the wife of Harry B. Murphy sued the company for negligence due to failing to provide proper safeguards. she was asking for $50,000.[31]

World War II service[]

After the Attack on Pearl Harbor, the Federal Government requisitioned the Northland and Southland on July 9, 1942. The company is given 24-hour notice with no details on what they will be used for or if they will be paid.[32] They are given to the British Allies. They were used in a decoy convoy along with several other ships in the area of St. Johns, Newfoundland on September 21, 1942. They were used to draw German submarines away from another convoy carrying thousands of troops. The Southerland's gun crew is credited with a "probable kill" a U-boat in the mid-Atlantic. The crew shot 14 rounds out of the 12-pounder to a periscope which had appeared on the starboard quarter. It was followed with a second emerging on the port quarter leading to 18 shells being sot. Only five of the eleven American ships made it to Great Britain, including the two steamers. All masters and chief engineers and 14 other officers received decorations from King George VI.[33][3]

The vessels were used to train British commandos and Royal Marines. The Northland was renamed the Layden as there was already another Northland in the Navy.[33]

The steamboats were then used in the Normandy landings of June 6, 1944. The British D-Day planners were looking for vessels able to cross the British Channel to be transport personnel or serve as hospital ships.[33] The District and Maryland men from the 29th Division landing on Omaha Beach recognized the steamboats and wrote about the excitement of seeing these local boats in letters home. While the idea of buying back the boats had been entertained, the state-rooms had been ripped out to make room for the troop hammocks. The cost was to great and they were sold to Chinese interest though it was not clear is the Communist or the Nationalists had them. The company was paid $338,275 by the government for the two steamboats.[3]

End of the company[]

With the Northland and Southland in the war, the company was operating the service with only one steamer by 1945: the District of Columbia. They did not return to the company after the war.[33]

In October 1948, the steamer was involved in a crash with a tanker in Hampton Roads. A passenger was killed and several others were injured. A $25,000 lawsuit was filed on December 20, 1948 by the Texas Company accusing the steamboat of going too fast in a foggy area and being outside of the Norfolk channel as the time of the incident.[34]

On November 26, 1948, after 58 years of service, the Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company published a legal noticed published in the local newspapers calling for a board of directors meeting recommending the liquidation of the company. The primary reason for this closure had to do with the high cost of equipment replacement. It had $940,000 in Government securities and the physical assets were valued at $269,000 in "floating equipment" (the District of Columbia), the Norfolk Terminal ($108,000), the Alexandria Wharf ($11,000) and their Maine Avenue office ($26,000).[3]

Boats[]

- George Leary

- Washington

- Norfolk

- Newport News

- Jamestown

- Northland

- Southland

- District of Columbia

See also[]

- Maine Avenue Fish Market

- Long Bridge (Potomac River)

- Steamboat

- Washington, D.C.

- Norfolk, Virginia

- Alexandria, Virginia

References[]

- ^ Route map of the Norfolk & Washington Steamboat Company and a plan of the S.S. District of Columbia

- ^ a b c A Palace Boat - The Daily Critic - November 22, 1890

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Capital's Steamboat Era Ends As Norfolk Line Closes Down" - Evening Star - November 28, 1948 - p. A-21

- ^ Washington Steamboat Company - Alexandria Gazette - January 4, 1890

- ^ The Washington Critic - February 20, 1890 - p. 3

- ^ Alexandria Gazette - March 6, 1890

- ^ The Washington Floats - The Evening Star - November 22, 1890

- ^ The Critic - Evening Edition - March 12, 1891

- ^ Town talk - The Sunday Herald - March 29, 1891

- ^ Lease of a Wharf Site Recommended - Evening Star September 29, 1890

- ^ Potomac Palaces - The Critic - January 10, 1890 - Front Page

- ^ Fears of Flood - The Evening Star - February 7, 1895 - p. 2

- ^ Local Intelligence - Alexandria Gazette - Evening Edition - September 13, 1894

- ^ Local Intelligence - Alexandria Gazette - Evening Edition - September 15, 1894

- ^ Local Intelligence - Alexandria Gazette - Evening Edition - November 16, 1894

- ^ The Evening Star - November 17, 1894

- ^ Local Intelligence - Alexandria Gazette - Evening Edition - November 19, 1894.

- ^ "Revocable Permit" - The Evening Star - March 11, 1895 - p. 12

- ^ Finished with Feast - The Evening Star - April 10, 1895

- ^ The New Steamer - Alexandria Gazette - June 7, 1895

- ^ "Newport News Coming to Washington" - The Evening Star - June 17, 1895

- ^ a b "The New River Boat" - The Evening Star - June 19, 1895 - Front Page

- ^ Southland Slides Down Ways to Bay - The Washington Times - October 3, 1908 - page 4

- ^ a b c d The Washington Times - September 2, 1918 - Final Edition - pp. 1–2

- ^ "New River Boat Takes to Water" - The Evening Star September 13, 1924 - page 2

- ^ Steamer Aground in Potomac Fog: Passengers Safe - The Evening Star - January 8, 1935 - Front Page

- ^ Man Held After Mate Of Ship Disappeared Will Fight Extradition - The Evening Star - April 16, 1941 - p. A-7

- ^ Ex- V.M.I Athlete Accused of Murder on Norfolk Steamer - The Evening Star - April 15, 1941 - Front Page

- ^ Body Found in Potomac Believed Missing Mate's - The Evening Star - April 30, 1941 - page XX

- ^ Jury Quickly Frees Reutt In Death of Steamer Mate - Evening star - November 26, 1941 - Page B-1

- ^ Wife of Mate Lost in River Sues Ship Firm for $50,000 - Evening star - March 26, 1942 - p. 3

- ^ U.S. Takes Over Two Noted Boats Plying Potomac - July 9, 1942 - Front Page

- ^ a b c d "Washington Steamer Southland Gets 'Probable"in U-Boat War" - Evening Star - May 20, 1945 - p. A-6

- ^ "Norfolk & Washington Line Sued in October Collision" - The Evening Star - December 21, 1948

- Potomac River

- Defunct shipping companies of the United States

- History of Washington, D.C.