Virginia Military Institute

| |

| Motto | Latin: In Pace Decus, In Bello Praesidium[1] |

|---|---|

Motto in English | In Peace a Glorious Asset, In War a Tower of Strength |

| Type | Public senior military college |

| Established | 11 November 1839 |

| Endowment | $539.6 million (2020)[2] |

| Superintendent | Cedric T. Wins[3] |

Academic staff | 143 full-time and 55 part-time (Fall 2019)[4] |

| Students | 1,685[4] |

| Location | Lexington , Virginia , United States 37°47′24″N 79°26′24″W / 37.790°N 79.440°WCoordinates: 37°47′24″N 79°26′24″W / 37.790°N 79.440°W[5] |

| Campus | Small town, 134 acres (0.54 km2) |

| Colors | Red, yellow, white[6] |

| Nickname | Keydets |

Sporting affiliations | National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA Division I) Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) – Southern Conference (SoCon) |

| Mascot | "Moe the Kangaroo"[7] |

| Website | vmi |

| |

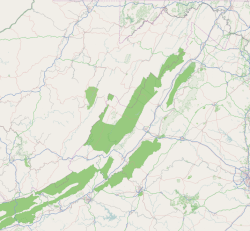

Location in Shenandoah Valley | |

Virginia Military Institute (VMI) is a public senior military college in Lexington, Virginia. It was founded in 1839 as America's first state military college and is the oldest public senior military college in the United States. In keeping with its founding principles and unlike any other senior military college in the United States, VMI enrolls cadets only and awards bachelor's degrees exclusively. VMI offers its students, all of whom are cadets, strict military discipline combined with a physically and academically demanding environment. The institute grants degrees in 14 disciplines in engineering, science, and the liberal arts,[8] and all VMI students are required to participate in ROTC.[9]

While Abraham Lincoln first called VMI "The West Point of the South",[10] because of its role during the American Civil War, the nickname has remained because VMI has produced more Army generals than any ROTC program in the United States. Despite the nickname, VMI differs from the federal military service academies in many regards. For example, as of 2019, VMI had a total enrollment of 1,722 cadets (as compared to 4,500 at the Academies) making it one of the smallest NCAA Division I schools in the United States. Additionally, today (as in the 1800s) all VMI cadets sleep on cots and live closely together in a more spartan and austere barracks environment than at the Service Academies.[11] All VMI cadets must participate in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) of the United States Armed Forces programs, but are afforded the flexibility of pursuing civilian endeavors or accepting an officer's commission in any of the active or reserve components of any of the U.S. military branches upon graduation, excluding the United States Coast Guard.[12]

VMI's alumni include a Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, Secretary of the Army, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, 7 Medal of Honor recipients, 13 Rhodes Scholars, Pulitzer Prize winners, an Academy Award winner, an Emmy Award and Golden Globe winner, a martyr recognized by the Episcopal Church, Senators and Representatives, Governors, including the current Governor of Virginia, Lieutenant Governors, a Supreme Court Justice, numerous college and university presidents, many business leaders (presidents and CEOs) and over 290 general and flag officers across all US service branches and several other countries.

Governance[]

The Board of Visitors is the supervisory board[13] of the Virginia Military Institute.[14][15] Although the Governor is ex officio the commander-in-chief of the institute, and no one may be declared a graduate without his signature, he delegates to the board the responsibility for developing the institute's policy.[15] The board appoints the superintendent and approves appointment of members of the faculty and staff on the recommendation of the superintendent.[15] The board may make bylaws and regulations for their own government and the management of the affairs of the institute,[16] and while the institute is exempt from the Administrative Process Act in accordance with Va. Code (which exempts educational institutions operated by the Commonwealth),[17] some of its regulations are codified at 8VAC 100. The Executive Committee conducts the business of the board during recesses.[14][18]

The board has 17 members, including ex officio the Adjutant General of the Commonwealth of Virginia.[15] Regular members are appointed by the Governor for a four-year term and may be reappointed once.[15] Of the sixteen appointed members, twelve must be alumni of the institute, eight of whom must be residents of Virginia and four must be non-residents; and the remaining four members must be non-alumni Virginia residents.[15] The Executive Committee consists of the board's president, three vice presidents, and one non-alumnus at large, and is appointed by the board at each annual meeting.[18]

Under the militia bill (the Virginia Code of 1860) officers of the institute were recognized as part of the military establishment of the state, and the governor had authority to issue commissions to them in accordance with institute regulations.[15] Current law makes provision for officers of the Virginia Militia to be subject to orders of the Governor.[15] The cadets are a military corps (the Corps of Cadets) under the command of the superintendent and under the administration of the Commandant of Cadets, and constitute the guard of the institute.[15][19]

History[]

Early history[]

In the years after the War of 1812, the Commonwealth of Virginia built and maintained several arsenals to store weapons intended for use by the state militia in the event of invasion or slave revolt. One of them was placed in Lexington. Residents came to resent the presence of the soldiers, whom they saw as drunken and undisciplined. In 1826, one guard beat another to death. Townspeople wanted to keep the arsenal, but sought a new way of guarding it, so as to eliminate the "undesirable element."[20][21] In 1834, the Franklin Society, a local literary and debate society, debated, "Would it be politic for the State to establish a military school, at the Arsenal, near Lexington, in connection with Washington College, on the plan of the West Point Academy?" They unanimously concluded that it would. Lexington attorney John Thomas Lewis Preston became the most active advocate of the proposal. In a series of three anonymous letters in the Lexington Gazette in 1835, he proposed replacing the arsenal guard with students living under military discipline, receiving some military education, as well as a liberal education. The school's graduates would contribute to the development of the state and, should the need arise, provide trained officers for the state's militia.[20][22]

After a public relations campaign that included Preston meeting in person with influential business, military and political figures and many open letters from prominent supporters including Alden Partridge of Norwich University, in 1836 the Virginia legislature passed a bill authorizing creation of a school at the Lexington arsenal, and the Governor signed the measure into law.[23][24][25]

The organizers of the planned school formed a board of visitors, which included Preston, and the board selected Claudius Crozet as their first president. Crozet had served as an engineer in Napoleon Bonaparte's army before immigrating to the United States. In America, he served as an engineering professor at West Point, as well as state engineer in Louisiana and mathematics professor at Jefferson College in Convent, Louisiana.[26] Crozet was also the Chief Engineer of Virginia and someone whom Thomas Jefferson referred to as, "the smartest mathematician in the United States." The board delegated to Preston the task of deciding what to call the new school, and he created the name Virginia Military Institute.[27]

Under Crozet's direction, the board of visitors crafted VMI's program of instruction, basing it off of those of the United States Military Academy and Crozet's alma mater the École Polytechnique of Paris. So, instead of the mix of military and liberal education imagined by Preston, the board created a military and engineering school offering the most thorough engineering curriculum in America, outside of West Point.[28]

Preston was also tasked with hiring VMI's first Superintendent. He was persuaded that West Point graduate and former Army officer Francis Henney Smith, then professor of mathematics at Hampden–Sydney College, was the most suitable candidate. Preston successfully recruited Smith, and convinced him to become the first Superintendent and Professor of Tactics.[20]

After Smith agreed to accept the Superintendent's position, Preston applied to join the faculty, and was hired as Professor of Languages.[29] Classes began in 1839, and the first cadet to march a sentinel post was Private John Strange.[30] With few exceptions, there have been sentinels posted at VMI every hour of every day of the school year since 11 November 1839.

The Class of 1842 graduated 16 cadets. Living conditions were poor until 1850 when the cornerstone of the new barracks was laid. In 1851 Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson became a member of the faculty and professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy. Under Jackson, then a major, and Major William Gilham, VMI infantry and artillery units were present at the execution by hanging of John Brown at Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1859.

Civil War period[]

VMI cadets and alumni played instrumental roles in the American Civil War. On 14 occasions, the Confederacy called cadets into active military engagements. VMI authorized battle streamers for each one of these engagements but chose to carry only one: the battle streamer for New Market. Many VMI Cadets were ordered to Camp Lee, at Richmond, to train recruits under General Stonewall Jackson. VMI alumni were regarded among the best officers of the South and several distinguished themselves in the Union forces as well. Fifteen graduates rose to the rank of general in the Confederate Army, and one rose to this rank in the Union Army.[31] Just before his famous flank attack at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Jackson looked at his division and brigade commanders, noted the high number of VMI graduates and said, "The Institute will be heard from today."[32] Three of Jackson's four division commanders at Chancellorsville, Generals James Lane, Robert Rodes, and Raleigh Colston, were VMI graduates as were more than twenty of his brigadiers and colonels.[32]

Battle of New Market[]

On 14 May 1864, the Governor of Virginia once again called upon the cadets from VMI to participate in the American Civil War. After marching overnight 80 miles from Lexington to New Market, on 15 May 1864, 247 members of the VMI Corps of Cadets fought at the Battle of New Market. This event marks the only time in U.S. history wherein the student body of an operating college fought as an organized unit in pitched combat in battle (as recognized by the American Battlefield Trust).[33][34] This event was the 14th time VMI Cadets were called into action during the Civil War.

At New Market, in a matter of minutes, VMI suffered fifty-five casualties with ten cadets killed; the cadets were led into battle by the Commandant of Cadets and future VMI Superintendent Colonel Scott Shipp. Shipp was also wounded during the battle. Six of the ten fallen cadets are buried on VMI grounds behind the statue "Virginia Mourning Her Dead" by sculptor Moses Ezekiel, a VMI graduate who was also wounded in the Battle of New Market.[35]

General John C. Breckinridge, the commanding Southern general, held the cadets in reserve and did not use them until Union troops broke through the Confederate lines. Upon seeing the tide of battle turning in favor of the Union forces, Breckinridge stated, "Put the boys in...and may God forgive me for the order."[36] The VMI cadets held the line and eventually pushed forward across an open muddy field, capturing a Union artillery emplacement, and securing victory for the Confederates. The Union troops were withdrawn and Confederate troops under General Breckinridge held the Shenandoah Valley.

Burning of the Institute[]

On 12 June 1864 Union forces, under the command of General David Hunter, shelled and burned the Institute as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864. The destruction was almost complete, and VMI had to temporarily hold classes at the Alms House in Richmond, Virginia. In April 1865 Richmond was evacuated due to the impending fall of Petersburg and the VMI Corps of Cadets was disbanded. The Lexington campus reopened for classes on 17 October 1865.[37] One of the reasons that Confederate General Jubal A. Early burned the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, was in retaliation for the destruction of VMI.[38]

Following the war, Matthew Fontaine Maury, the pioneering oceanographer known as the "Pathfinder of the Seas", accepted a teaching position at VMI, holding the physics chair. Following the war, David Hunter Strother, who was chief of staff to General Hunter and had advised the destruction of the Institute, served as Adjutant General of the Virginia Militia and member of the VMI Board of Visitors; in that position he promoted and worked actively for the reconstruction.

World War II[]

VMI produced many of America's commanders in World War II. The most important of these was George C. Marshall, the top U.S. Army general during the war. Marshall was the Army's first five-star general and the only career military officer ever to win the Nobel Peace Prize.[39] Winston Churchill dubbed Marshall the "Architect of Victory" and "the noblest Roman of them all". The Deputy Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army during the war was also a VMI graduate as were the Second U.S. Army commander, 15th U.S. Army commander, the commander of Allied Air Forces of the Southwest Pacific and various corps and division commanders in the Army and Marine Corps. China's General Sun Li-jen, known as the "Rommel of the East", was also a graduate of VMI.[40]

During the war, VMI participated in the War Department's Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) from 1943 to 1946. The program provided training in engineering and related subjects to enlisted men at colleges across the United States. Over 2,100 ASTP members studied at VMI during the war.

Post World War II[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (October 2020) |

VMI admitted its first female student in 1995 after the U.S. Justice Department pursued a seven-year long lawsuit against the institution alleging discrimination. Although that first female student dropped out soon after matriculating, 30 female students enrolled in 1997, cementing VMI's new status as a coeducational institution.[41]

On 19 October 2020, following an exposé in the Washington Post, Governor Ralph Northam and multiple other state officials wrote the VMI Board of Visitors that they had "deep concerns about the clear and appalling culture of ongoing structural racism” at VMI.[42] They reported that they had received reports from students of a racist culture at VMI. The students reported a threat of lynching, attacks on social media, and a staff member promoting "an inaccurate and dangerous 'Lost Cause' version of Virginia's history."[43] The letter was signed by Northam, Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax, Virginia House Speaker Eileen Filler-Corn, state Senate President Louise Lucas, Attorney General Mark Herring, and chairman of the Black caucus Lamont Bagby.[43] Northam, a 1981 VMI alumnus, ordered a state-led investigation.[43]

Six days later, on 26 October 2020, Superintendent Gen. J.H. Binford Peay tendered his resignation, saying in his resignation letter that he'd been told that Governor Northam and other state legislators had "lost confidence in my leadership" and "desired my resignation".[44][45] Three days later, the VMI Board of Visitors voted unanimously to remove from campus the statue of Confederate hero Stonewall Jackson, a former VMI professor, and create a building and naming committee.[46] The school reaffirmed the statue's removal in December and began plans to relocated it to a Civil War museum located on a battlefield where a number of VMI cadets and alumni were killed or wounded.[47]

In October, the board also announced several diversity-related decisions: a diversity officer would be appointed, a diversity and inclusion committee would be created, and diversity initiatives created to include a focus on gender and the adoption of a diversity hiring plan.[46] Nine months later, a report into racial intolerance charged by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia was delivered. The independent report concluded that VMI "maintained and allowed a racist and sexist culture that, until recently, it had no appetite to address." The authors, employed by the law firm Barnes & Thornburg, also accused the institution's leadership, including its governing board, with an "unwillingness to change or even question its practices."[48]

Superintendents[]

Since 1839, VMI has had fifteen superintendents. Francis H. Smith was the first and the longest serving, filling the position for 50 years. Twelve of the fifteen superintendents were graduates of VMI.

- Francis H. Smith (1839–1889), United States Military Academy West Point Class of 1833

- Scott Shipp '59 (1890–1907), wounded leading VMI cadets into The Battle of New Market[49]

- Edward W. Nichols '78 (1907–1924)

- William H. Cocke '94 (1924–1929)

- John A. Lejeune (1929–1937), United States Naval Academy Class of 1888, 13th Commandant of the Marine Corps

- Charles E. Kilbourne '94 (1937–1946), Medal of Honor recipient and first American to earn the United States' three highest military decorations.[50][better source needed]

- Richard J. Marshall '15 (1946–1952)

- William H. Milton, Jr. '20 (1952–1960)

- George R. E. Shell '31 (1960–1971)

- Richard L. Irby '39 (1971–1981)

- Sam S. Walker (1981–1988), matriculated at VMI transferred to United States Military Academy West Point Class of 1946

- John W. Knapp '54 (1989–1995)

- Josiah Bunting III '63 (1995–2002)

- J. H. Binford Peay III '62 (2003–2020)

- Cedric T. Wins '85 (2021–present)

Campus[]

Virginia Military Institute Historic District | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

Virginia Landmarks Register | |

Virginia Military Institute campus | |

| |

| Location | VMI campus, Lexington, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 12 acres (4.9 ha) |

| Built | 1818 |

| Architect | Davis, A.J.; Goodhue, Bertram Grosvenor |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival, Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002219[51] |

| VLR No. | 117-0017 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 30 May 1974 |

| Designated VLR | 9 September 1969[52] |

The VMI campus covers 134 acres (54 ha), 12 of which are designated as the Virginia Military Institute Historic District, a designated National Historic Landmark District. The campus is referred to as the "Post," a tradition that reflects the school's military focus and the uniformed service of its alumni. A training area of several hundred additional acres is located near the post. All cadets are housed on campus in a large five-story building, called the "barracks." The Old Barracks, which has been separately designated a National Historic Landmark, stands on the site of the old arsenal. This is the structure that received most of the damage when Union forces shelled and burned the Institute in June 1864. The new wing of the barracks ("New Barracks") was completed in 1949. The two wings surround two quadrangles connected by a sally port. All rooms open onto porch-like stoops facing one of the quadrangles. A third barracks wing was completed, with cadets moving in officially spring semester 2009. Four of the five arched entries into the barracks are named for George Washington, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, George C. Marshall '901[53] and Jonathan Daniels '61.[54] Next to the Barracks are offices and meeting areas for VMI clubs and organizations, the cadet visitors center and lounge, a snack bar, and a Follett Corporation-operated bookstore.

VMI's "Vision 2039" capital campaign raised more than $275 million from alumni and supporters in three years. The money is going to expand The Barracks to house 1,500 cadets, renovate and modernize the academic buildings. VMI is spending another $200 million to build the VMI Center for Leadership and Ethics, to be used by cadets, Washington and Lee University students, and other U.S. and international students. The funding will also support "study abroad" programs, including joint ventures with Oxford and Cambridge Universities in England and many other universities.[55]

In October 2020, VMI Board of Visitors announced that the institute will relocate a statue of Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, a Confederate general and slave owner, from the front of the historic barracks to potentially the Battle of New Market.[56][57] It was taken from view in December.[58]

Academics[]

VMI offers 14 major and 23 minor areas of study,[59] grouped into engineering, liberal arts, humanities, and the sciences. The engineering department has concentrations in three areas: civil and environmental engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and mechanical engineering.[60] Most classes are taught by full-time professors, 99 percent of whom hold terminal degrees.[60]

Within four months of graduation, an average of 97 percent of VMI graduates are either serving in the military, employed, or admitted to graduate or professional schools.[61]

As of 2010, VMI had graduated 11 Rhodes Scholars since 1921.[62][63] Per capita, as of 2006 VMI had graduated more Rhodes Scholars than any other state-supported college or university, and more than all the other senior military colleges combined.

Rankings[]

In 2015 VMI ranked fourth nationally, after the United States Military Academy, the United States Naval Academy and the United States Air Force Academy, in the U.S. News and World Report rankings' "Top Public Schools, National Liberal Arts Colleges" category.[64]

Forbes' 2012 Special Report on America's Best Colleges ranked VMI in the top 25 public universities in the nation, well ahead of any other senior military college in the country. VMI was ranked 14th in the "Top 25 Publics" section, just behind the United States Military Academy, the United States Air Force Academy, and the United States Naval Academy, but ahead of the United States Coast Guard Academy and the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy.[65] Overall, VMI ranked 115th out of the 650 colleges and universities evaluated.[66]

Kiplinger's magazine, in its ranking of the "Best Values in Public Colleges" for 2006, made mention of the Virginia Military Institute as a "great value", although the military nature of its program excluded it from consideration as a traditional four-year college in the rankings.[67]

Military service[]

While all cadets are required to take four years of ROTC, accepting a commission in the armed forces is optional. While over 50 percent of VMI graduates are commissioned each year, the VMI Board of Visitors has set a goal of having 70 percent of VMI cadets take a commission.[68] The VMI class of 2017 graduated 300 cadets, 172 (or 57 percent) of whom were commissioned as officers in the United States military.[69]

VMI alumni include more than 285 general and flag officers, including the first five-star General of the Army, George Marshall;[70] seven recipients of the highest U.S. military decoration, the Medal of Honor; and more than 80 recipients of the second-highest awards, the Distinguished Service Cross and Navy Cross.[71] VMI offers ROTC programs for four U.S. military branches (Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force).

VMI has graduated more Army generals than any ROTC program in the United States.[72] The following table lists U.S. four-star generals who graduated from VMI. It does not list alumni who did not graduate from the school, such as General George S. Patton and General Sam S. Walker, and the many VMI graduates who served or still serve as four-star generals in foreign nations such as Thailand, China, and Taiwan.

| Name | VMI class | Branch & date of rank |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Marshall | 1901 | Army, 1 September 1939 |

|

| Thomas T. Handy | 1916 | Army, 13 March 1945 |

|

| Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr. | 1917 | USMC, 1 January 1952 |

|

| Leonard T. Gerow | 1911 | Army, 19 July 1954 |

|

| Randolph M. Pate | 1921 | USMC, 1 January 1956 |

|

| Clark L. Ruffner | 1924 | Army, 1 March 1960 |

|

| David M. Maddox | 1960 | Army, 9 July 1992 |

|

| J. H. Binford Peay III | 1962 | Army, 26 March 1993 |

|

| John P. Jumper | 1966 | Air Force, 17 November 1997 |

|

| Darren W. McDew | 1982 | Air Force, 5 May 2014 |

|

Students[]

Prospective cadets must be between 16 and 22 years of age. They must be unmarried, and have no legal dependents, be physically fit for enrollment in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), and be graduates of an accredited secondary school or have completed an approved homeschool curriculum. The Class of 2022 at VMI had an average high school GPA of 3.70 and a mean SAT score of 1210.[73]

Eligibility is not restricted to Virginia residents, although it is more difficult to gain an appointment as a non-resident, because VMI has a goal that no more than 45 percent of cadets come from outside Virginia.[74] Virginia residents receive a discount in tuition, as is common at most state-sponsored schools. Total tuition, room & board, and other fees for the 2008–2009 school year was approximately $17,000 for Virginia residents and $34,000 for all others.[75]

Of 509 students that matriculated in August 2012, just 46 were women.[76] The first Jewish cadet, Moses Jacob Ezekiel, graduated in 1866. While at VMI, Ezekiel fought with the VMI cadets at the Battle of New Market.[77] He became a sculptor and his works are on display at VMI. One of the first Asian cadets was Sun Li-jen, the Chinese National Revolutionary Army general, who graduated in 1927. The first African-American cadets were admitted in 1968. The first African-American regimental commander was Darren McDew, class of 1982. McDew is a retired U.S. Air Force General and former Commander, United States Transportation Command, Scott Air Force Base, IL. It is unknown when the first Muslim cadet graduated from VMI, but before the Iranian Revolution of 1979, under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, several Persian cadets attended and graduated from VMI. Other Muslim graduates have included cadets from Bangladesh, Jordan, Indonesia, Somalia and other nations.

Admission of women[]

In 1997, VMI ended its prohibition and became the last U.S. military college to admit women. Superintendent at the time Josiah Bunting III called this a "savage disappointment".[44]

In 1990 the U.S. Department of Justice filed a discrimination lawsuit against VMI for its all-male admissions policy. While the court challenge was pending, a state-sponsored Virginia Women's Institute for Leadership (VWIL) was opened at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, as a parallel program for women. The VWIL continued, even after VMI's admission of women.[78]

After VMI won its case in U.S. District Court, the case went through several appeals until 26 June 1996, when the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 7–1 decision in United States v. Virginia, found that it was unconstitutional for a school supported by public funds to exclude women. (Justice Clarence Thomas recused himself, presumably because his son was attending VMI at the time.) Following the ruling, VMI contemplated going private to exempt itself from the 14th Amendment, and thus avoid the ruling.[10]

Assistant Secretary of Defense Frederick Pang, however, warned the school that the Department of Defense would withdraw ROTC programs from the school if privatization took place. As a result of this action by Pang, Congress passed a resolution on 18 November 1997 prohibiting the Department of Defense from withdrawing or diminishing any ROTC program at one of the six senior military colleges, including VMI. This escape clause provided by Congress came after the VMI Board of Visitors had already voted 9–8 to admit women; the decision was not revisited.[10]

In August 1997, VMI enrolled its first female cadets. The first co-ed class consisted of thirty women, and matriculated as part of the class of 2001. In order to accelerate VMI's matriculation process several women were allowed to transfer directly from various junior colleges, such as New Mexico Military Institute (NMMI), and forgo the traditional four-year curriculum that most cadets had been subjected to. The first female cadets "walked the stage" in 1999, although by VMI's definitions they are considered to be members of the class of 2001. Initially, these 30 women who were held to the same strict physical courses and technical training as the male cadets until it became apparent that adjustments to the standards had to be made.[according to whom?] VMI resisted following other military colleges in adopting "gender-normed" physical training standards until 2008 when it was listed as a goal in VMI's 2039 Strategic Plan.[79][80] On 30 June 2008, gender-normed training standards were implemented for all female cadets.[81]

Admission of Black students[]

Virginia Military Institute was the last public college in Virginia to integrate, first admitting black cadets in 1968,[82] but interracial problems persist to the present day.[83] According to the Washington Post, even in 2020 "Black cadets still endure relentless racism [in an] atmosphere of hostility and cultural insensitivity".[83]

Student life[]

Just as cadets did nearly 200 years ago, today's cadets give up such comforts as beds, instead lying upon cots colloquially referred to as "hays". These hays are little more than foam mats that must be rolled every morning and aired every Monday. Further, cadet uniforms have changed little; the coatee worn in parades dates to the War of 1812. New cadets, known as "Rats", are not permitted to watch TV or listen to music outside of an academic setting. Living conditions are considered more austere here than other service academies.[84]

Ratline[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

During the first six months at VMI, New Cadets are called "Rats," the accepted term (since the 1850s) for a New Cadet. The VMI ratline is a tough, old-fashioned indoctrination-system which dates back to the institute's founding. All "Rats" refer to their classmates, male or female, as "Brother Rats." The term "Brother Rat" is a term of endearment which lasts a lifetime amongst VMI graduates. Legend has it that when Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) students and VMI cadets drilled together in the 1830s, the students called the cadets "Rats" perhaps because of their gray uniforms. The cadets responded in kind calling the neighboring students "Minks" perhaps because many of them were from wealthy backgrounds. The purpose of the Ratline is to teach self-control, self-discipline, time-management, and followership as prerequisites for becoming a VMI cadet.[85]

New freshmen, known collectively as the "Rat Mass", walk along a prescribed line in barracks while maintaining an exaggerated form of attention, called "straining". This experience, called the Rat Line, is intended by the upper classes to instill camaraderie, pride, and discipline into the incoming class. Under this system, the Rats face numerous mental and physical challenges, starting with "Hell Week." During Hell Week, Rats receive basic military instruction from select upper classmen ("Cadre"); they learn to march, to clean their M14 rifle, and to wear their uniforms. During Hell Week, Rats also meet the members of various cadet-run organizations and learn the functions of each.

At the end of the first week, each Rat is paired with a first classman (senior) who serves as their mentor for the rest of the first year. The first classman is called a "Dyke," reference to an older Southern pronunciation of "to deck out," or to get into a uniform, as one of the roles of the rat is to help prepare their "Dyke's" uniform and dress them for parades.[86] While the Dyke watches out for the Rat and the Rat works for the Dyke in accordance with Institute policy, Cadre still enforce all rules for the Rats. The combination of the warm relationship with the Dykes and the harshness of the school system, with countless push-ups, sweat parties, and runs, is calculated to instill the required military outlook and competence on everyday tasks in the Rats.

The Ratline experience culminates with Resurrection Week ending in "Breakout," an event where the Rats are formally "welcomed" to the VMI community. After the successful completion of Breakout, Rats are officially fourth class students and no longer have to strain in the barracks or eat "square meals." Many versions of the Breakout ceremony have been conducted. In the 1950s, Rats from each company would be packed into a corner room in the barracks and brawl their way out through the upperclassmen. From the late 1960s through the early 1980s the Rats had to fight their way up to the fourth level of the barracks through three other classes of cadets determined not to let them get to the top. The stoops would often be slick with motor oil, packed with snow, glazed with ice, greased, or continuously hosed with water. The barracks stairs and rails were not able to take the abuse, so the Corps moved the breakout to a muddy hill, where Rats attempt to climb to the top by crawling on their stomachs while the upper classes block them or drag them back down.[86] The Rats no longer breakout in the mud but instead participate in a grueling day of physical activity testing both physical endurance and teamwork.

The entire body of Rats during the Ratline is called a "Rat Mass." Since Rats are not officially fourth classmen until after Breakout, the Rat Mass is also not officially considered a graduating class until that time either. Prior to Breakout, the Rat mass is given a different style of year identifier to emphasize this difference. The year identifier starts with the year of the current graduating class (their dykes' class), followed by a "+3" to indicate the anticipated year of their own class. For example, cadets that make up the Class of 2022 were considered the "Rat Mass of 2019+3" as the members of their dykes' class graduated in 2019 and they themselves will graduate three years onward from then.

Traditions[]

In addition to the Ratline, VMI has other traditions that are emblematic of the school and its history including the new cadet oath ceremony, the pageantry of close-order marching, and the nightly playing of "Taps". An event second only to graduation in importance is the "Ring Figure" dance held every November. During their junior year, cadets receive class rings at a ring presentation ceremony followed by a formal dance.[87] Most cadets get two rings, a formal ring and a combat ring; some choose to have the combat ring for everyday wear, and the formal for special occasions.

Every year, VMI honors its fallen cadets with a New Market Day parade and ceremony. These events take place on 15 May, the same day as the Battle of New Market in which VMI cadets fought in 1864 during the . During this ceremony, the roll is called for cadets who "died on the Field of Honor" and wreaths are placed on the graves of those who died during the Battle of New Market.[88]

The requirement that all cadets wishing to eat dinner in the mess hall must be present for a prayer was the basis for a lawsuit in 2002 when two cadets sued VMI over the prayer said before dinner.[89] The non-denominational prayer had been a daily fixture since the 1950s.[90][91][92] In 2002 the Fourth Circuit ruled the prayer, during an event with mandatory attendance, at a state-funded school, violated the U.S. Constitution. When the Supreme Court declined to review the school's appeal in April 2004, the prayer tradition was stopped.[93]

The tradition of guarding the institute is one of the longest standing and is carried out to this day. Cadets have been posted as sentinels guarding the barracks 24 hours a day, seven days a week while school is in session since the first cadet sentinel, Cadet John B. Strange, and others relieved the Virginia Militia guard team tasked with defending the Lexington Arsenal (that later became VMI) in 1839. The guard team wears the traditional school uniform and each sentinel is armed with an M14 rifle and bayonet.[94]

Honor code[]

VMI is known for its strict honor code, which is as old as the Institute and was formally codified in the early 20th century.[95] Under the VMI Honor Code, "a cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, nor tolerate those who do."[95][96] There is only one punishment for violating the VMI Honor Code: immediate expulsion in the form of a drumming out ceremony of dismissal, in which the entire corps is awakened by drums in barracks and the honor court to hear the formal announcement. VMI is the only military college or academy in the Nation which maintains a single-sanction Honor Code and in recent times, the dismissed cadet is removed from post before the formal announcement is made.[97]

Clubs and activities[]

VMI currently offers over 50 school-sponsored clubs and organizations, including recreational activities, military organizations, musical and performance groups, religious organizations and service groups.[98][99] Although VMI prohibited cadet membership in fraternal organizations starting in 1885, VMI cadets were instrumental in starting several fraternities. Alpha Tau Omega fraternity was founded by VMI cadets , Alfred Marshall, and Erskine Mayo Ross at Richmond, Virginia on 11 September 1865 while the school was closed for reconstruction.[100]

After the re-opening, Kappa Sigma Kappa fraternity was founded by cadets on 28 September 1867 and Sigma Nu fraternity was founded by cadets on 1 January 1869.[95] VMI cadets formed the second chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order.[101] In a special arrangement, graduating cadets may be nominated by Kappa Alpha Order alumni and inducted into the fraternity, becoming part of Kappa Alpha Order's Beta Commission (a commission as opposed to an active chapter). This occurs following graduation, and the newly initiated VMI alumni are accepted as brothers of the fraternity.[102]

Athletics[]

VMI fields 14 teams on the NCAA Division I level (FCS, formerly I-AA, for football). Varsity sports include baseball, basketball, men's and women's cross country, football, lacrosse, men's and women's rifle, men's and women's soccer, men's and women's swimming & diving, men's and women's track & field, and wrestling. VMI is a member of the Southern Conference (SoCon) for almost all sports, the MAAC for women's water polo, and the America East Conference for men's and women's swimming & diving.[103] VMI formerly was a member of the Mid-Atlantic Rifle Conference for rifle, but began the 2016–2017 season as part of the Southern Conference.[104] The VMI team name is the Keydets, a Southern style slang for the word "cadets".

VMI has the second-smallest NCAA Division I enrollment of any FCS football college, after Presbyterian College.[105] Approximately one-third of the Corps of Cadets plays on at least one of VMI's intercollegiate athletic teams, making it one of the most active athletic programs in the country. Of the VMI varsity athletes who complete their eligibility, 92 percent receive their VMI degrees.[106]

Football[]

VMI played its first football game in 1871. The one-game season was a 4–2 loss to Washington and Lee University. There are no records of a coach or any players for that game.[107] VMI waited another twenty years, until 1891, when head coach Walter Taylor would coach the next football team.[108] The current head football coach at VMI, Scott Wachenheim, was named the 31st head coach on 14 December 2014.[109] The Keydets play their home games out of Alumni Memorial Field at Foster Stadium, built in 1962. VMI won the 2020 Southern Conference Football Championship, their first winning football season since 1981.[110]

Men's basketball[]

Perhaps the most famous athletic story in VMI history was the two-year run of the 1976 and 1977 basketball teams. The 1976 squad advanced within one game of the Final Four before bowing to undefeated Rutgers in the East Regional Final, and in 1977 VMI finished with 26 wins and just four losses, still a school record, and reached the "Sweet 16" round of the NCAA tournament.

The current VMI basketball team is led by head coach Dan Earl and assistant coaches: Steve Enright and Austin Kenon. Tom Kiely is the Director of Basketball Operations.

Alumni[]

VMI's alumni include the current Governor of Virginia, the 24th Secretary of the Army, a Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, Pulitzer Prize winners, 13 Rhodes Scholars, Medal of Honor recipients, an Academy Award winner, an Emmy Award and Golden Globe winner, a martyr recognized by the Episcopal Church, Senators and Representatives, Governors, Lieutenant Governors, a Supreme Court Justice, numerous college and university presidents, many business leaders (presidents and CEOs) and over 285 general and flag officers, including service chiefs for three of the four armed services.

Two recent Chiefs of Engineers of the Army Corps of Engineers, Lieutenant Generals Carl A. Strock and Robert B. Flowers, as well as Acting Chief of Engineers Major General "Bo" Temple, were VMI Civil Engineering graduates.[111]

Endowment[]

A 2007 study by the National Association of College and University Business Officers found that VMI's $343 million endowment was the largest per-student endowment of any U.S. public college in the United States.[112][113][verification needed] 35.4 percent of the approximately 12,300 living alumni gave in 2006.[114] Private support covers more than 31 percent of VMI's operating budget; state funds, 26 percent.

In popular culture[]

- Ronald Reagan starred in the films Brother Rat and Brother Rat and a Baby, which were filmed at VMI. Originally a Broadway hit, the play was written by John Monks Jr. and Fred F. Finklehoffe, both 1932 graduates of VMI.[115]

- Both the novel and film Gods and Generals depict Stonewall Jackson teaching at VMI before Virginia secedes. The film also depicts Jackson's funeral at VMI.

- In 2014, the film Field of Lost Shoes premiered in Richmond to the Corps of Cadets and the cast. The film depicts the Battle of New Market in 1864. VMI now owns and operates this historical battlefield museum and site.

See also[]

- Virginia Defense Force

- Virginia National Guard

References[]

- ^ "History of the VMI Coat of Arms, Motto, Seal & Spider Logo". Virginia Military Institute. n.d. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ As of June 30, 2020. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Maj. Gen. Cedric Wins '85 to lead Virginia Military Institute". www.vmi.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/?q=Virginia+Military+Institute&s=all&id=234085

- ^ "Virginia Military Institute". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ^ VMI Visual Identity Standards Manual (PDF). Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Virginia Military Institute: Quick Facts". About Virginia Military Institute. Lexington, VA: Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "VMI Quick Facts". Vmi.edu. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Academics - Academics - Virginia Military Institute". www.vmi.edu.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Strum, Philippa (2004). Women in the Barracks: The VMI Case and Equal Rights. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1336-6.

- ^ "Best Colleges - Virginia Military Institute". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ "VMI ROTC". Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Va. Code § 2.2-2100

- ^ Jump up to: a b Va. Code § 23-92

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Virginia Military Institute Faculty Handbook". January 2014. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Va. Code § 23-99

- ^ VA.R. Doc. No. R12-3076 (19 December 2011)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Board of Visitors By-Laws § 6(8)

- ^ Va. Code § 23-109

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wineman, Bradford (2006). "J.T.L. Preston and the Origins of the Virginia Military Institute, 1834-42". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 114 (2): 246. JSTOR 4250312.

- ^ Strum, Philippa (2002). Women in the Barracks: The VMI Case and Equal Rights. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 9. ISBN 9780700611645.

- ^ Southern California Review of Law and Women's Studies, Volume 5. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California. 1995. pp. 232, 235.

- ^ Couper, William (1936). Claudius Crozet. Palisades, NY: Historical Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 93, 100.

- ^ Andrew, Rod, Jr. (2001). Long Gray Lines: The Southern Military School Tradition, 1839-1915. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-8078-2610-3.

- ^ Farwell, Byron (1992). Stonewall: A Biography of General Thomas J. Jackson. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 87. ISBN 0-393-31086-8.

- ^ Hunter, Robert F., and Edwin L. Dooley, Jr. (1989). Claudius Crozet: French Engineer in America, 1790-1861. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. pp. 10–11, 14, 17, 85, 98.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. New York, NY: J. T. White. 1967. p. 245.

- ^ Miller, Jonson (2020). Engineering Manhood: Race and the Antebellum Virginia Military Institute. Lever Press. pp. 104–105, 113–114. doi:10.3998/mpub.11675767. ISBN 9781643150178.

- ^ Governor's Message and Reports of the Public Officers of the State, of the Board of Directors, and of the Visitors, Superintendents, and Other Agents of Public Institutions or Interests of Virginia. Richmond, VA: William F. Ritchie. 1855. p. 27.

- ^ Farwell, Byron (1993). Stonewall: A Biography of General Thomas J. Jackson. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-393-31086-3.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 April 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), VMI Archives

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sears, Stephen W., "Chancellorsville". Mariner Books, 1996, p. 242. (link to 1998 edition)

- ^ "Battle of New Market – Shenandoah at War".

- ^ "The Battle of New Market". American Battlefield Trust. 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Virginia Mourning Her Dead". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Andrew, Rod Jr. (2004). Long Gray Lines: The Southern Military School Tradition, 1839–1915. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8078-5541-6.

- ^ "VMI Civil War Chronology". Archived from the original on 12 January 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2013.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ "The Burning of Chambersburg". Angelfire.com. 22 September 2001. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Nordlinger, Jay (20 March 2012). Peace, They Say: A History of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Most Famous and Controversial Prize in the World. Encounter Books. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-59403-598-2. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Letters, Diaries and Manuscripts Guide. VMI Faculty & Alumni Papers". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Finn, Peter (17 March 1998). "VMI Women Reach End of Rat Line". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Probe ordered of VMI after Post's report on racist incidents". The News Leader (Staunton, Virginia). 21 October 2020. p. A4 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McLaughlin, Eliott C. (21 October 2020). "After cadets allege racism in news reports, state orders review of Virginia Military Institute's culture". CNN. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shapira, Ian (26 October 2020). "VMI superintendent resigns after Black cadets describe relentless racism". Washington Post.

- ^ Mitchell, Ellen (26 October 2020). "Virginia Military Institute superintendent resigns after allegations of racism surface". The Hill. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hite, Patrick (31 October 2020). "VMI votes to remove Stonewall Jackson statue". The News Leader (Staunton, Virginia). p. A2.

- ^ Associated Press (7 December 2020). "Virginia Military Institute removing Confederate statue". Politico. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Burke, Lilah (2 June 2021). "'Silence, Fear and Intimidation'". Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "VMI Website: VMI Superintendents, 1839–present". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Rolf of Ebon: A Novel of Romance, War and Adventure in Ancient England, Charles E. Kilbourne, Exposition Press, New York, 1962, p. 171.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "VMI Alumni Flag Rank Officers – Alumni Generals & Admirals" (PDF). Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Jonathan Myrick Daniels (VMI Class of 1961) Civil Rights Hero". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Vision 2039 – Focus on Leadership". VMI. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Wyatt, William (29 October 2020). "Actions of the VMI Board of Visitors". Virginia Military Institute (Press release). Lexington, Virginia. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Greta (30 October 2020). "VMI to Relocate Confederate Statue". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Rankin, Sarah (7 December 2020). "Virginia Military Institute removes Confederate statue". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ "Majors, Minors, Certificates". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "VMI: Academic Departments". Vmi.edu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "VMI Engineering". Virginia Military Institute. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Cadet Named VMI's 11th Rhodes Scholar". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "VMI Rhodes Scholars". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Top Public Schools National Liberal Arts Colleges".

- ^ "Best Public Colleges 2012– VMI". U.S. News and World Report. 1 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "America's Best Colleges Ranking List". Forbes. America's Best Colleges. 1 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Lankford, Kimberly (February 2006). "Best Values in Public Colleges". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. 60 (2): 90. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Vision 2039 Focus on Leadership". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "VMI 2017 Graduation". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "VMI Profile". VMI Keydets.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ "Medal of Honor". VMI Museum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ "Viewbook". VMI.edu.

- ^ "Profile of the Class of 2015" (PDF). VMI. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "VMI Vision 2039 Document" (PDF). Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Virginia Military Institute - Page Not Found". vmi.edu. Cite uses generic title (help)

- ^ "509 Matriculate in Class of 2016". VMI. 18 August 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Jacob, Kathryn Allamong (1998). Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington. JHU Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8018-5861-1.

- ^ Cabe, Crista (1 March 2005). "MBC Celebrates VWIL's 10th Anniversary March 18, 2004" Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Mary Baldwin College web site.

- ^ "showcontent". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ VMI Operational Plans and Progress Report 2008 Strategy 1–13

- ^ "showcontent". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/09/09/vmi-stonewall-jackson-statue/?hpid=hp_local1-8-12_vmi-305am%3Ahomepage%2Fstory-ans. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Shapira, Ian (17 October 2020). "At VMI, Black cadets endure lynching threats, Klan memories and Confederacy veneration". The Washington Post.

- ^ "USA Military schools".

- ^ "Virginia Military Institute - Purpose of the Ratline". Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weinstein, Laurie Lee; Christie C. White (1997). Wives and Warriors: Women and the Military in the United States and Canada. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-0-89789-491-3.

- ^ "Cadet Life: Class Rings and Ring Figure The History of a VMI Tradition". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Couper, William; Keith E. Gibson (2005). The Corps Forward: The Biographical Sketches of the VMI Cadets who Fought in the Battle of New Market. Mariner Companies, Inc. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-9768238-2-7.

- ^ "ACLU Files Lawsuit to Stop Coerced Prayers at Virginia Military Institute". Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Josiah Bunting, III, and J. H. Binford Peay, III, Superintendent, Virginia Military Institute v. Neil J. Mellen and Paul S. Knick, 03-863 Stevens, J., (p. 1) (Supreme Court of the United States 26 April 2004) ("In sum, we have before us in this petition a constitutional issue of considerable consequence on which the Courts of Appeals are in disagreement.").

- ^ "ACLU Defends Prayer Ban at VMI". Atheism.about.com. 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 18 September 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ McGough, Michael (27 April 2004). "Supreme Court justices in sharp exchange over refusal to hear VMI prayer case". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Virginia Military Institute - Page Not Found". vmi.edu. Cite uses generic title (help)

- ^ "John B. Strange, Class of 1842. The First Sentinel". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "VMI History FAQ". Vmi.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "VMIhonor".

- ^ Chittum, Matt (9 March 1997). "The honor code is 'simple and all-encompassing'". Roanoke Times. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "Clubs and Organizations". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Academic & Professional Societies". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "ATO website". Ato.org. 26 April 1931. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Shelton, Todd. "Our Kappa Alpha Heritage". Kappa Alpha Order. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Beta Commission". Retrieved 17 August 2014.

Our Commission system allows for men to be elected and initiated into Kappa Alpha Order if they are graduating seniors, graduates, faculty, staff or administrators.

- ^ "Men's Swimming & Diving to Return as Championship Sport; VMI Joins as Associate Member" (Press release). America East Conference. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Rifle Teams Head to WVU for Sectional" (Press release). VMIKeydets.com. 17 February 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Columbia, SC Breaking News, Sports, Weather & More - TheState.com & The State". www.thestate.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ^ VMI Athletic History – A Brief Look Archived 26 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine (9 August 2002). VMI web site.

- ^ DeLassus, David. "Virginia Military Institute Yearly Results: 1873". College Football Data Warehouse. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ DeLassus, David. "Virginia Military Institute Coaching Records". College Football Data Warehouse. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "VMI News Release on Hiring". Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ^ King, Randy (20 September 2012). "Keydets hope to upset, get first win against Navy". The Roanoke Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Stars Shine in Run-up to Commencement". The Institute Report. XXXI (7): 1 & 14. 16 April 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "VMI Athletics and the VMI Keydet Club Website". Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ "All Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2008 Market Value of Endowment Assets with Percentage Change Between 2007 and 2008 Endowment Assets" (PDF). 2008 NACUBO Endowment Study. National Association of College and University Business Officers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Belliveau, Scott (June 2007). "Foundation Fund: Business as Usual". The Institute Report. XXXIV (7): 6. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Vaughn, Stephen (28 January 1994). Ronald Reagan in Hollywood: Movies and Politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-521-44080-6. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

Further reading[]

- Andrew, Rod, Jr. (2001). Long Gray Lines: The Southern Military School Tradition, 1839-1915. University of North Carolina Press.

- Brodie, Laura Fairchild (2000). Breaking Out: VMI and the Coming of Women. New York: Vintage.

- Couper, William (1939). One Hundred Years at V.M.I, Volumes One to Four. Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie.

- Davis, Thomas W., ed. (1988). A Crowd of Honorable Youths: Historical Essays on the First 150 Years of the Virginia Military Institute. Lexington, VA: VMI Sesquicentennial Committee.

- Green, Jennifer R. (2008). Military Education and the Emerging Middle Class in the Old South. Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, Jonson (2020). Engineering Manhood: Race and the Antebellum Virginia Military Institute. Lever Press.

- Pancake, John, Virginia Reveres Civil War Bravery, The Washington Post

- Strum, Philippa (2002). Women in the Barracks: The VMI Case and Equal Rights. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Wineman, Bradford (2006). "J.T.L. Preston and the Origins of the Virginia Military Institute, 1834-1842." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 114, no. 2: 226–261.

- Wise, Henry A. (1978). Drawing Out the Man: The VMI Story. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Wise, Jennings C. (1915). The Military History of the Virginia Military Institute, from 1839-1865. Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Virginia Military Institute. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Virginia Military Institute". |

- Official website

- VMI Athletics website

- Wikisource:Virginia Military Institute—Building and Rebuilding Virginia Military Institute Building and Rebuilding.

- Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- Virginia Military Institute

- University and college buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia

- Military academies of the United States

- National Historic Landmarks in Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places in Lexington, Virginia

- Public universities and colleges in Virginia

- United States senior military colleges

- Education in Lexington, Virginia

- Universities and colleges accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

- Educational institutions established in 1839

- Buildings and structures in Lexington, Virginia

- Tourist attractions in Lexington, Virginia

- 1839 establishments in Virginia

- Military education and training in the United States

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Virginia