Nuba peoples

The Nuba people are various indigenous ethnic groups who inhabit the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan state in Sudan, encompassing multiple distinct people that speak different languages which belong to at least two unrelated language families. Estimates of the Nuba population vary widely; the Sudanese government estimated that they numbered 2.07 million in 2003.[1]

The term should not be confused with the Nubians, an ethnic group speaking the Nubian languages, although the Hill Nubians, who live in the Nuba Mountains, are also considered part of the Nuba geographic grouping of peoples. It is important to note that, the Nubaians in South Kordofan believe that they are affiliates of the ancient Nubian kingdoms. [2]

Description[]

Dwellings[]

The Nuba people reside in the foothills of the Nuba Mountains. Villages consist of family compounds, and the men's (Holua) in which unmarried men sleep.

A family compound consisting of a rectangular compound enclosing two round mud huts thatched with sorghum stalks facing each other called a shal. The shal was fenced with wooden posts interwoven with straw. Two benches ran down the each side of the shal with a fire in the middle where families will tell stories and oral traditions. Around the shal was the much larger yard, the tog placed in front. The fence of the tog was made of strong tree branches as high as the roof of the huts. Small livestock like goats and chickens and donkeys were kept in the tog. Each compound had tall conical granaries called durs which stood on one side of the tog. At the back of the compound was a small yard were maize and vegetables like pumpkin, beans and peanuts were grown.

For families that were small a compound was not needed and a mud hut with a fence would be enough. The entrance was as large as a man so people could climb the ladder and dive in to get grain. Inside the hut there was very little furniture, only a bamboo bed frame with a baobab rope mat on top and the hearth in the middle with firewood. Possessions and tools were hung or leaned against the wall. A small garden behind the hut was used to grow vegetables like beans and pumpkin while sorghum and peanuts were grown away in the hills. One's wealth is measured by cattle so they are kept in an enclosure called a coh for cows and a cohnih for calves. The Nuba people eat sorghum as their staple. It is boiled with water or milk to make kal eaten with meat stew called waj. Corn is also roasted and eaten with home made butter.

Languages[]

The Nuba people speak various languages not closely related to each other. Most of the Nuba people speak one of the many languages in the geographic Kordofanian languages group of the Nuba Mountains. This language group is primarily in the major Niger–Congo language family. Several Nuba languages are in the Nilo-Saharan language family.[3]

Over one hundred languages are spoken in the area and are considered Nuba languages, although many of the Nuba also speak Sudanese Arabic, the common language of Sudan.

Culture[]

The Nuba people are primarily farmers, as well as herders who keep cattle, chickens, and other domestic animals. They often maintain three different farms: a garden near their homes where vegetables needing constant attention, such as onions, peppers and beans, are grown; fields further up the hills where quick growing crops such as red millet can be cultivated without irrigation; and farms farther away, where white millet and other crops are planted.[4]

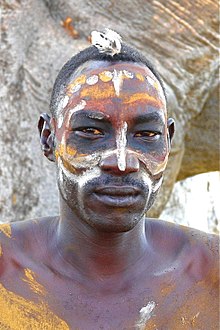

A distinctive characteristic of the Nubas is their passion for athletic competition, particularly traditional wrestling.[5] The strongest young men of a community compete with athletes from other villages for the chance to promote their personal and their village’s pride and strength. In some villages, older men participate in club- or spear-fighting contests. The Nubas’ passion for physical excellence is also displayed through the young men’s vanity—they often spend hours painting their bodies with complex patterns and decorations. This vanity reflects the basic Nuba belief in the power and importance of strength and beauty.

Religions[]

The primary religion of many Nuba people is Islam, with some Christians, and traditional shamanistic beliefs also prevailing.[6] Men wear a sarong and occasionally a skull cap. Young men remained naked, while children wear only a string of beads. Older women and young women wear beads and wrap a sarong over their legs and sometimes a cloak tie on the shoulder. Both sexes practice scarification and circumcision for boys and female genital mutilation for girls. Men shave their heads, older men wear beards, women and girls braid their hair in strands and string it with beads.

The majority of the Nuba living in the east, west and northern parts of the mountains are Muslims, while those living to the south are either Christians or practice traditional animistic religions. In those areas of the Nuba mountains where Islam has not deeply penetrated, ritual specialists and priests hold as much control as the clan elders, for it is they who are responsible for rain control, keeping the peace, and rituals to ensure successful crops. Many are guardians of the shrines where items are kept to insure positive outcomes of the rituals (such as rain stones for the rain magic), and some also undergo what they recognize as spiritual possession.

Politics[]

In the 1986 elections, the National Umma Party lost several seats to the Nuba Mountains General Union and to the Sudan National Party, due to the reduced level of support from the Nuba Mountains region. There is reason to believe that attacks by the government-supported militia, the Popular Defense Force (PDF), on several Nuba villages were meant to be in retaliation for this drop in support, which was seen as signaling increased support of the SPLA. The PDF attacks were particularly violent, and have been cited as examples of crimes against humanity that took place during the Second Sudanese Civil War[7]

Nuba Mountains[]

The Nuba people reside in one of the most remote and inaccessible places in all of Sudan, the foothills of the Nuba Mountains in central Sudan. At one time the area was considered a place of refuge, bringing together people of many different tongues and backgrounds who were fleeing oppressive governments and slave traders.

The Nuba Mountains mark the southern border of the sands of the desert and the northern limit of good soils washed down by the Nile River. Many Nuba, however, have migrated to the Sudanese capital of Khartoum to escape persecution and the effects of Sudan’s civil war. Most of the rest of the 1,000,000 Nuba people live in villages and towns of between 1,000 and 50,000 inhabitants in areas in and surrounding the Nuba mountains. Nuba villages are often built where valleys run from the hills out on to the surrounding plains, because water is easier to find at such points and wells can be used all year long. There is no political unity among the various Nuba groups who live on the hills. Often the villages do not have chiefs, but are instead organized into clans or extended family groups with village authority left in the hands of clan elders.

War in the Nuba Mountains[]

Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)[]

After some earlier incursions by the SPLA, the Second Sudanese Civil War started full scale in the Nuba Mountains when the Volcano Battalion of the SPLA under the command of the Nuba Yousif Kuwa Mekki and Abdel Aziz Adam al-Hillu entered the Nuba Mountains and began to recruit Nuba volunteers and send them to SPLA training facilities in Ethiopia. The volunteers walked to Ethiopia and back and many of them perished on the way.

During the war, the SPLA generally held the Mountains, while the Sudanese Army held the towns and fertile lands at the feet of the Mountains, but was generally unable to dislodge the SPLA, even though the latter was usually very badly supplied. The Governments of Sudan under Sadiq al-Mahdi and Omar al-Bashir also armed militias of Baggara Arabs to fight the Nuba and transferred many Nuba forcibly to camps.

In early 2002 the Government and the SPLA agreed on an internationally supervised ceasefire. International observers and advisors were quickly dispatched to Kadugli base camp and several deployed into the mountains to co-located with SPLA command elements. The base camp at Kauda for several observers included Swiss African advisor, French diplomat, an Italian and an American former US Army officer.

At that time, Abdel Aziz Adam al-Hillu was the governor of Nuba Mountains. During the course of the following months, relief supplies from the UN were air dropped to stem the starvation of many in Nuba Mountains.

The ceasefire in Nuba Mountains was the foundation for the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in January 2005. This fragile peace remains in force, but infighting in the south, plus the Government of Sudan involvement in Darfur have resulted in issues which may break the peace agreement.

Secession of South Sudan (2011)[]

Southern Sudan voted for secession from Sudan in the Southern Sudanese independence referendum, 2011. This provision was agreed to in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). The secession victory established the formation of a new country, South Sudan, from the southern portion of Sudan. However, conflict between Northern and Southern forces, and against the Nuba peoples, renewed again in the region in 2011 — see Sudan–SPLM-N conflict (2011) for detailed information.

Media[]

- Film maker documented Bisha TV,[8] a satirical muppet show popular throughout the Nuba lands, which serves as an "example of how people use comedy to deal with authoritarian rule." The show mocks Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, depicting him as the killer of children and bomber of hospitals. A short documentary by Gogineni includes apparent bombing of Kauda by a Soviet-made Antonov airplane. It shows a public screening of Bisha TV in front of dozens of local residents.[9]

- Eyes and Ears Of God – Video surveillance of Sudan (2012) film by peace activist Tomo Križnar on YouTube. The documentary film shows the ethnic Nuba civilians defending themselves with the help of over 400 cameras distributed by himself and Klemen Mihelič, the founder of humanitarian organisation H.O.P.E., to volunteers across the war zones in the Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, and Darfur, documenting the (North) Sudan military's war crimes against local populations.[10][11]

- Leni Riefenstahl, better known for her films Triumph of the Will and Olympia of Nazi Germany, published two collections of her photographs of Nuba peoples, entitled The Last of the Nuba (1973) and The People of Kau (1976).

- Nuba Conversations (2000), a documentary and ethnographic film directed by Arthur Howes.

See also[]

|

|

- Index: Nuba peoples

Footnotes[]

- ^ South Kordofan

- ^ Winter, Roger (2000), Spaulding, Jay; Beswick, Stephanie (eds.), "The Nuba People: Confronting Cultural Liquidation", White Nile Black Blood: War, Leadership, and Ethnicity from Khartoum to Kampala, Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, archived from the original on 2000-04-09

- ^ Bell, Herman (1995-12-03). "The Nuba Mountains: Who Spoke What in 1976?". A Communication Presented to the Third Conference on Language in Sudan.

- ^ Bedigian, Dorothea; Harlan, Jack R. (1983). "Nuba Agriculture and Ethnobotany, with Particular Reference to Sesame and Sorghum". Economic Botany. 37 (4): 384–395. doi:10.1007/BF02904199. JSTOR 4254532. S2CID 41581798.

- ^ Anele, Uzonna (January 20, 2020). "Nuba Wrestling: A Look into Sudan's Nuba People and their Traditional Wrestling Culture". listwand.com.

- ^ "Sudan: Nuba". Miniority Rights Group.

Some traditional religions survive but most Nuba have been converted to Islam or Christianity.

- ^ Salih (1999)

- ^ "Bisha TV". Facebook.

- ^ Gogineni, Roopa (2017-10-03). "The Rebel Puppeteers of Sudan". The New York Times.

- ^ About the documentary on Tomo Križnar's website

- ^ Žerdin, Ali (3 June 2016). "Portret tedna: Tomo Križnar". old.delo.si (in Slovenian).

Further reading[]

- Op 't Ende, Nanne (2007). Proud to be Nuba: Faces and Voices : Stories of a Long Struggle. Code X Publishing. ISBN 978-90-78233-02-2.

- Salih, Mohamed (1999). Environmental Politics and Liberation in Contemporary Africa. Environment & Policy. 18. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9165-2. ISBN 978-0-7923-5652-3.

- Seligmann, Brenda Z. (1910). "Note on the language of the Nubas of Southern Kordofan". Zeitschrift fur Kolonialsprachen. D. Reimer. 1: 167–88.

- Stevenson, R. C. (1963). "Some Aspects of the Spread of Islam in the Nuba Mountains". Sudan Notes and Records. 44: 9–20. ISSN 0375-2984. JSTOR 41716839.

- Stevenson, R.C., Adjectives in Nyimang offprint, as above

- Stevenson, R. C. (1962). "Linguistic Research in the Nuba Mountains - I". Sudan Notes and Records. 43: 118–130. ISSN 0375-2984. JSTOR 41716826.

- Stevenson, R. C. (1964). "Linguistic Research in the Nuba Mountains - II". Sudan Notes and Records. 45: 79–102. ISSN 0375-2984. JSTOR 41716860.

- Stevenson, R. C. (1940). "The Nyamang of the Nuba Mountains of Kordofan". Sudan Notes and Records. 23 (1): 75–98. ISSN 0375-2984. JSTOR 41716394.

- Stevenson, R. C. (1984). The Nuba people of Kordofan Province: an ethnographic survey. Khartoum, Sudan: Graduate College, University of Khartoum. ISBN 978-0-86372-020-8.

- Samuel, Totten (2012). Genocide by Attrition : The Nuba Mountains of Sudan. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203790861. ISBN 978-0-203-79086-1.

- Totten, Samuel; Grzyb, Amanda F., eds. (2015). Conflict in the Nuba Mountains : From Genocide-by-Attrition to the Contemporary Crisis in Sudan. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203755877. ISBN 9781135015350.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuba people. |

- "Tomo križnar in Sudan". - A Slovenian peace activist in Sudan, helping the Nuba peoples

- "Nuba Survival". Archived from the original on 2019-01-24. Nuba indigenous rights organization

- Winter, Roger (2000). "The Nuba and their Homeland".

- "Nuba Languages". Archived from the original on 1999-01-28.

- "Nuba Culture". nubasurvival.com. Archived from the original on 2004-12-05.

- The Nuba Mountains Homepage

- The Linguistic Settlement of the Nuba Mountains

- Nuba People by Fr. Yousif William

- Full documentary about the sufferings of the Nuba

- Nuba peoples

- Ethnic groups in Sudan