Numerical analysis

Numerical analysis is the study of algorithms that use numerical approximation (as opposed to symbolic manipulations) for the problems of mathematical analysis (as distinguished from discrete mathematics). Numerical analysis finds application in all fields of engineering and the physical sciences, and in the 21st century also the life and social sciences, medicine, business and even the arts. Current growth in computing power has enabled the use of more complex numerical analysis, providing detailed and realistic mathematical models in science and engineering. Examples of numerical analysis include: ordinary differential equations as found in celestial mechanics (predicting the motions of planets, stars and galaxies), numerical linear algebra in data analysis,[2][3][4] and stochastic differential equations and Markov chains for simulating living cells in medicine and biology.

Before modern computers, numerical methods often relied on hand interpolation formulas, using data from large printed tables. Since the mid 20th century, computers calculate the required functions instead, but many of the same formulas continue to be used in software algorithms.[5]

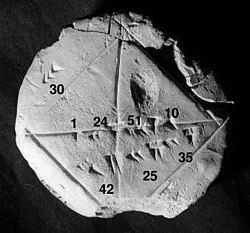

The numerical point of view goes back to the earliest mathematical writings. A tablet from the Yale Babylonian Collection (YBC 7289), gives a sexagesimal numerical approximation of the square root of 2, the length of the diagonal in a unit square.

Numerical analysis continues this long tradition: rather than giving exact symbolic answers translated into digits and applicable only to real-world measurements, approximate solutions within specified error bounds are used.

General introduction[]

The overall goal of the field of numerical analysis is the design and analysis of techniques to give approximate but accurate solutions to hard problems, the variety of which is suggested by the following:

- Advanced numerical methods are essential in making numerical weather prediction feasible.

- Computing the trajectory of a spacecraft requires the accurate numerical solution of a system of ordinary differential equations.

- Car companies can improve the crash safety of their vehicles by using computer simulations of car crashes. Such simulations essentially consist of solving partial differential equations numerically.

- Hedge funds (private investment funds) use tools from all fields of numerical analysis to attempt to calculate the value of stocks and derivatives more precisely than other market participants.

- Airlines use sophisticated optimization algorithms to decide ticket prices, airplane and crew assignments and fuel needs. Historically, such algorithms were developed within the overlapping field of operations research.

- Insurance companies use numerical programs for actuarial analysis.

The rest of this section outlines several important themes of numerical analysis.

History[]

The field of numerical analysis predates the invention of modern computers by many centuries. Linear interpolation was already in use more than 2000 years ago. Many great mathematicians of the past were preoccupied by numerical analysis,[5] as is obvious from the names of important algorithms like Newton's method, Lagrange interpolation polynomial, Gaussian elimination, or Euler's method.

To facilitate computations by hand, large books were produced with formulas and tables of data such as interpolation points and function coefficients. Using these tables, often calculated out to 16 decimal places or more for some functions, one could look up values to plug into the formulas given and achieve very good numerical estimates of some functions. The canonical work in the field is the NIST publication edited by Abramowitz and Stegun, a 1000-plus page book of a very large number of commonly used formulas and functions and their values at many points. The function values are no longer very useful when a computer is available, but the large listing of formulas can still be very handy.

The mechanical calculator was also developed as a tool for hand computation. These calculators evolved into electronic computers in the 1940s, and it was then found that these computers were also useful for administrative purposes. But the invention of the computer also influenced the field of numerical analysis,[5] since now longer and more complicated calculations could be done.

Direct and iterative methods[]

Consider the problem of solving

- 3x3 + 4 = 28

for the unknown quantity x.

| 3x3 + 4 = 28. | |

| Subtract 4 | 3x3 = 24. |

| Divide by 3 | x3 = 8. |

| Take cube roots | x = 2. |

For the iterative method, apply the bisection method to f(x) = 3x3 − 24. The initial values are a = 0, b = 3, f(a) = −24, f(b) = 57.

| a | b | mid | f(mid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 1.5 | −13.875 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 2.25 | 10.17... |

| 1.5 | 2.25 | 1.875 | −4.22... |

| 1.875 | 2.25 | 2.0625 | 2.32... |

From this table it can be concluded that the solution is between 1.875 and 2.0625. The algorithm might return any number in that range with an error less than 0.2.

Discretization and numerical integration[]

In a two-hour race, the speed of the car is measured at three instants and recorded in the following table.

| Time | 0:20 | 1:00 | 1:40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | 140 | 150 | 180 |

A discretization would be to say that the speed of the car was constant from 0:00 to 0:40, then from 0:40 to 1:20 and finally from 1:20 to 2:00. For instance, the total distance traveled in the first 40 minutes is approximately (2/3 h × 140 km/h) = 93.3 km. This would allow us to estimate the total distance traveled as 93.3 km + 100 km + 120 km = 313.3 km, which is an example of numerical integration (see below) using a Riemann sum, because displacement is the integral of velocity.

Ill-conditioned problem: Take the function f(x) = 1/(x − 1). Note that f(1.1) = 10 and f(1.001) = 1000: a change in x of less than 0.1 turns into a change in f(x) of nearly 1000. Evaluating f(x) near x = 1 is an ill-conditioned problem.

Well-conditioned problem: By contrast, evaluating the same function f(x) = 1/(x − 1) near x = 10 is a well-conditioned problem. For instance, f(10) = 1/9 ≈ 0.111 and f(11) = 0.1: a modest change in x leads to a modest change in f(x).

Direct methods compute the solution to a problem in a finite number of steps. These methods would give the precise answer if they were performed in infinite precision arithmetic. Examples include Gaussian elimination, the QR factorization method for solving systems of linear equations, and the simplex method of linear programming. In practice, finite precision is used and the result is an approximation of the true solution (assuming stability).

In contrast to direct methods, iterative methods are not expected to terminate in a finite number of steps. Starting from an initial guess, iterative methods form successive approximations that converge to the exact solution only in the limit. A convergence test, often involving the residual, is specified in order to decide when a sufficiently accurate solution has (hopefully) been found. Even using infinite precision arithmetic these methods would not reach the solution within a finite number of steps (in general). Examples include Newton's method, the bisection method, and Jacobi iteration. In computational matrix algebra, iterative methods are generally needed for large problems.[6][7][8][9]

Iterative methods are more common than direct methods in numerical analysis. Some methods are direct in principle but are usually used as though they were not, e.g. GMRES and the conjugate gradient method. For these methods the number of steps needed to obtain the exact solution is so large that an approximation is accepted in the same manner as for an iterative method.

Discretization[]

Furthermore, continuous problems must sometimes be replaced by a discrete problem whose solution is known to approximate that of the continuous problem; this process is called 'discretization'. For example, the solution of a differential equation is a function. This function must be represented by a finite amount of data, for instance by its value at a finite number of points at its domain, even though this domain is a continuum.

Generation and propagation of errors[]

The study of errors forms an important part of numerical analysis. There are several ways in which error can be introduced in the solution of the problem.

Round-off[]

Round-off errors arise because it is impossible to represent all real numbers exactly on a machine with finite memory (which is what all practical digital computers are).

Truncation and discretization error[]

Truncation errors are committed when an iterative method is terminated or a mathematical procedure is approximated, and the approximate solution differs from the exact solution. Similarly, discretization induces a discretization error because the solution of the discrete problem does not coincide with the solution of the continuous problem. For instance, in the iteration in the sidebar to compute the solution of , after 10 or so iterations, it can be concluded that the root is roughly 1.99 (for example). Therefore, there is a truncation error of 0.01.

Once an error is generated, it will generally propagate through the calculation. For instance, already noted is that the operation + on a calculator (or a computer) is inexact. It follows that a calculation of the type is even more inexact.

The truncation error is created when a mathematical procedure is approximated. To integrate a function exactly it is required to find the sum of infinite trapezoids, but numerically only the sum of only finite trapezoids can be found, and hence the approximation of the mathematical procedure. Similarly, to differentiate a function, the differential element approaches zero but numerically only a finite value of the differential element can be chosen.

Numerical stability and well-posed problems[]

Numerical stability is a notion in numerical analysis. An algorithm is called 'numerically stable' if an error, whatever its cause, does not grow to be much larger during the calculation.[10] This happens if the problem is 'well-conditioned', meaning that the solution changes by only a small amount if the problem data are changed by a small amount.[10] To the contrary, if a problem is 'ill-conditioned', then any small error in the data will grow to be a large error.[10]

Both the original problem and the algorithm used to solve that problem can be 'well-conditioned' or 'ill-conditioned', and any combination is possible.

So an algorithm that solves a well-conditioned problem may be either numerically stable or numerically unstable. An art of numerical analysis is to find a stable algorithm for solving a well-posed mathematical problem. For instance, computing the square root of 2 (which is roughly 1.41421) is a well-posed problem. Many algorithms solve this problem by starting with an initial approximation x0 to , for instance x0 = 1.4, and then computing improved guesses x1, x2, etc. One such method is the famous Babylonian method, which is given by xk+1 = xk/2 + 1/xk. Another method, called 'method X', is given by xk+1 = (xk2 − 2)2 + xk.[note 1] A few iterations of each scheme are calculated in table form below, with initial guesses x0 = 1.4 and x0 = 1.42.

| Babylonian | Babylonian | Method X | Method X |

|---|---|---|---|

| x0 = 1.4 | x0 = 1.42 | x0 = 1.4 | x0 = 1.42 |

| x1 = 1.4142857... | x1 = 1.41422535... | x1 = 1.4016 | x1 = 1.42026896 |

| x2 = 1.414213564... | x2 = 1.41421356242... | x2 = 1.4028614... | x2 = 1.42056... |

| ... | ... | ||

| x1000000 = 1.41421... | x27 = 7280.2284... |

Observe that the Babylonian method converges quickly regardless of the initial guess, whereas Method X converges extremely slowly with initial guess x0 = 1.4 and diverges for initial guess x0 = 1.42. Hence, the Babylonian method is numerically stable, while Method X is numerically unstable.

- Numerical stability is affected by the number of the significant digits the machine keeps on, if a machine is used that keeps only the four most significant decimal digits, a good example on loss of significance can be given by these two equivalent functions

- Comparing the results of

- and

- by comparing the two results above, it is clear that loss of significance (caused here by catastrophic cancellation from subtracting approximations to the nearby numbers and , despite the subtraction's being computed exactly) has a huge effect on the results, even though both functions are equivalent, as shown below

- The desired value, computed using infinite precision, is 11.174755...

- The example is a modification of one taken from Mathew; Numerical methods using Matlab, 3rd ed.

Areas of study[]

The field of numerical analysis includes many sub-disciplines. Some of the major ones are:

Computing values of functions[]

|

Interpolation: Observing that the temperature varies from 20 degrees Celsius at 1:00 to 14 degrees at 3:00, a linear interpolation of this data would conclude that it was 17 degrees at 2:00 and 18.5 degrees at 1:30pm. Extrapolation: If the gross domestic product of a country has been growing an average of 5% per year and was 100 billion last year, it might extrapolated that it will be 105 billion this year.  Regression: In linear regression, given n points, a line is computed that passes as close as possible to those n points.  Optimization: Say lemonade is sold at a lemonade stand, at $1 197 glasses of lemonade can be sold per day, and that for each increase of $0.01, one glass of lemonade less will be sold per day. If $1.485 could be charged, profit would be maximized but due to the constraint of having to charge a whole cent amount, charging $1.48 or $1.49 per glass will both yield the maximum income of $220.52 per day.  Differential equation: If 100 fans are set up to blow air from one end of the room to the other and then a feather is dropped into the wind, what happens? The feather will follow the air currents, which may be very complex. One approximation is to measure the speed at which the air is blowing near the feather every second, and advance the simulated feather as if it were moving in a straight line at that same speed for one second, before measuring the wind speed again. This is called the Euler method for solving an ordinary differential equation. |

One of the simplest problems is the evaluation of a function at a given point. The most straightforward approach, of just plugging in the number in the formula is sometimes not very efficient. For polynomials, a better approach is using the Horner scheme, since it reduces the necessary number of multiplications and additions. Generally, it is important to estimate and control round-off errors arising from the use of floating point arithmetic.

Interpolation, extrapolation, and regression[]

Interpolation solves the following problem: given the value of some unknown function at a number of points, what value does that function have at some other point between the given points?

Extrapolation is very similar to interpolation, except that now the value of the unknown function at a point which is outside the given points must be found.[11]

Regression is also similar, but it takes into account that the data is imprecise. Given some points, and a measurement of the value of some function at these points (with an error), the unknown function can be found. The least squares-method is one way to achieve this.

Solving equations and systems of equations[]

Another fundamental problem is computing the solution of some given equation. Two cases are commonly distinguished, depending on whether the equation is linear or not. For instance, the equation is linear while is not.

Much effort has been put in the development of methods for solving systems of linear equations. Standard direct methods, i.e., methods that use some matrix decomposition are Gaussian elimination, LU decomposition, Cholesky decomposition for symmetric (or hermitian) and positive-definite matrix, and QR decomposition for non-square matrices. Iterative methods such as the Jacobi method, Gauss–Seidel method, successive over-relaxation and conjugate gradient method[12] are usually preferred for large systems. General iterative methods can be developed using a matrix splitting.

Root-finding algorithms are used to solve nonlinear equations (they are so named since a root of a function is an argument for which the function yields zero). If the function is differentiable and the derivative is known, then Newton's method is a popular choice.[13][14] Linearization is another technique for solving nonlinear equations.

Solving eigenvalue or singular value problems[]

Several important problems can be phrased in terms of eigenvalue decompositions or singular value decompositions. For instance, the spectral image compression algorithm[15] is based on the singular value decomposition. The corresponding tool in statistics is called principal component analysis.

Optimization[]

Optimization problems ask for the point at which a given function is maximized (or minimized). Often, the point also has to satisfy some constraints.

The field of optimization is further split in several subfields, depending on the form of the objective function and the constraint. For instance, linear programming deals with the case that both the objective function and the constraints are linear. A famous method in linear programming is the simplex method.

The method of Lagrange multipliers can be used to reduce optimization problems with constraints to unconstrained optimization problems.

Evaluating integrals[]

Numerical integration, in some instances also known as numerical quadrature, asks for the value of a definite integral.[16] Popular methods use one of the Newton–Cotes formulas (like the midpoint rule or Simpson's rule) or Gaussian quadrature.[17] These methods rely on a "divide and conquer" strategy, whereby an integral on a relatively large set is broken down into integrals on smaller sets. In higher dimensions, where these methods become prohibitively expensive in terms of computational effort, one may use Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo methods (see Monte Carlo integration[18]), or, in modestly large dimensions, the method of sparse grids.

Differential equations[]

Numerical analysis is also concerned with computing (in an approximate way) the solution of differential equations, both ordinary differential equations and partial differential equations.[19]

Partial differential equations are solved by first discretizing the equation, bringing it into a finite-dimensional subspace.[20] This can be done by a finite element method,[21][22][23] a finite difference method,[24] or (particularly in engineering) a finite volume method.[25] The theoretical justification of these methods often involves theorems from functional analysis. This reduces the problem to the solution of an algebraic equation.

Software[]

Since the late twentieth century, most algorithms are implemented in a variety of programming languages. The Netlib repository contains various collections of software routines for numerical problems, mostly in Fortran and C. Commercial products implementing many different numerical algorithms include the IMSL and NAG libraries; a free-software alternative is the GNU Scientific Library.

Over the years the Royal Statistical Society published numerous algorithms in its Applied Statistics (code for these "AS" functions is here); ACM similarly, in its Transactions on Mathematical Software ("TOMS" code is here). The Naval Surface Warfare Center several times published its Library of Mathematics Subroutines (code here).

There are several popular numerical computing applications such as MATLAB,[26][27][28] TK Solver, S-PLUS, and IDL[29] as well as free and open source alternatives such as FreeMat, Scilab,[30][31] GNU Octave (similar to Matlab), and IT++ (a C++ library). There are also programming languages such as R[32] (similar to S-PLUS), Julia,[33] and Python with libraries such as NumPy, SciPy[34][35][36] and SymPy. Performance varies widely: while vector and matrix operations are usually fast, scalar loops may vary in speed by more than an order of magnitude.[37][38]

Many computer algebra systems such as Mathematica also benefit from the availability of arbitrary-precision arithmetic which can provide more accurate results.[39][40][41][42]

Also, any spreadsheet software can be used to solve simple problems relating to numerical analysis. Excel, for example, has hundreds of available functions, including for matrices, which may be used in conjunction with its built in "solver".

See also[]

- Analysis of algorithms

- Computational science

- Interval arithmetic

- List of numerical analysis topics

- Local linearization method

- Numerical differentiation

- Numerical Recipes

- Symbolic-numeric computation

- Validated numerics

Notes[]

- ^ This is a fixed point iteration for the equation , whose solutions include . The iterates always move to the right since . Hence converges and diverges.

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ "Photograph, illustration, and description of the root(2) tablet from the Yale Babylonian Collection". Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ Demmel, J. W. (1997). Applied numerical linear algebra. SIAM.

- ^ Ciarlet, P. G., Miara, B., & Thomas, J. M. (1989). Introduction to numerical linear algebra and optimization. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Trefethen, Lloyd; Bau III, David (1997). Numerical Linear Algebra (1st ed.). Philadelphia: SIAM.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brezinski, C., & Wuytack, L. (2012). Numerical analysis: Historical developments in the 20th century. Elsevier.

- ^ Saad, Y. (2003). Iterative methods for sparse linear systems. SIAM.

- ^ Hageman, L. A., & Young, D. M. (2012). Applied iterative methods. Courier Corporation.

- ^ Traub, J. F. (1982). Iterative methods for the solution of equations. American Mathematical Society.

- ^ Greenbaum, A. (1997). Iterative methods for solving linear systems. SIAM.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Higham, N. J. (2002). Accuracy and stability of numerical algorithms (Vol. 80). SIAM.

- ^ Brezinski, C., & Zaglia, M. R. (2013). Extrapolation methods: theory and practice. Elsevier.

- ^ Hestenes, Magnus R.; Stiefel, Eduard (December 1952). "Methods of Conjugate Gradients for Solving Linear Systems". Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 49 (6): 409.

- ^ Ezquerro Fernández, J. A., & Hernández Verón, M. Á. (2017). Newton’s method: An updated approach of Kantorovich’s theory. Birkhäuser.

- ^ Peter Deuflhard, Newton Methods for Nonlinear Problems. Affine Invariance and Adaptive Algorithms, Second printed edition. Series Computational Mathematics 35, Springer (2006)

- ^ The Singular Value Decomposition and Its Applications in Image Compression Archived 4 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Davis, P. J., & Rabinowitz, P. (2007). Methods of numerical integration. Courier Corporation.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Gaussian Quadrature." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. mathworld

.wolfram .com /GaussianQuadrature .html - ^ Geweke, J. (1995). Monte Carlo simulation and numerical integration. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Research Department.

- ^ Iserles, A. (2009). A first course in the numerical analysis of differential equations. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Ames, W. F. (2014). Numerical methods for partial differential equations. Academic Press.

- ^ Johnson, C. (2012). Numerical solution of partial differential equations by the finite element method. Courier Corporation.

- ^ Brenner, S., & Scott, R. (2007). The mathematical theory of finite element methods. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Strang, G., & Fix, G. J. (1973). An analysis of the finite element method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

- ^ Strikwerda, J. C. (2004). Finite difference schemes and partial differential equations. SIAM.

- ^ LeVeque, Randall (2002), Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Quarteroni, A., Saleri, F., & Gervasio, P. (2006). Scientific computing with MATLAB and Octave. Berlin: Springer.

- ^ Gander, W., & Hrebicek, J. (Eds.). (2011). Solving problems in scientific computing using Maple and Matlab®. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Barnes, B., & Fulford, G. R. (2011). Mathematical modelling with case studies: a differential equations approach using Maple and MATLAB. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- ^ Gumley, L. E. (2001). Practical IDL programming. Elsevier.

- ^ Bunks, C., Chancelier, J. P., Delebecque, F., Goursat, M., Nikoukhah, R., & Steer, S. (2012). Engineering and scientific computing with Scilab. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Thanki, R. M., & Kothari, A. M. (2019). Digital image processing using SCILAB. Springer International Publishing.

- ^ Ihaka, R., & Gentleman, R. (1996). R: a language for data analysis and graphics. Journal of computational and graphical statistics, 5(3), 299-314.

- ^ Bezanson, Jeff; Edelman, Alan; Karpinski, Stefan; Shah, Viral B. (1 January 2017). "Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing". SIAM Review. 59 (1): 65–98. doi:10.1137/141000671. hdl:1721.1/110125. ISSN 0036-1445.

- ^ Jones, E., Oliphant, T., & Peterson, P. (2001). SciPy: Open source scientific tools for Python.

- ^ Bressert, E. (2012). SciPy and NumPy: an overview for developers. " O'Reilly Media, Inc.".

- ^ Blanco-Silva, F. J. (2013). Learning SciPy for numerical and scientific computing. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- ^ Speed comparison of various number crunching packages Archived 5 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Comparison of mathematical programs for data analysis Archived 18 May 2016 at the Portuguese Web Archive Stefan Steinhaus, ScientificWeb.com

- ^ Maeder, R. E. (1991). Programming in mathematica. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- ^ Stephen Wolfram. (1999). The MATHEMATICA® book, version 4. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Shaw, W. T., & Tigg, J. (1993). Applied Mathematica: getting started, getting it done. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc..

- ^ Marasco, A., & Romano, A. (2001). Scientific Computing with Mathematica: Mathematical Problems for Ordinary Differential Equations; with a CD-ROM. Springer Science & Business Media.

Sources[]

- Golub, Gene H.; Charles F. Van Loan (1986). Matrix Computations (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5413-X.

- Higham, Nicholas J. (1996). Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 0-89871-355-2.

- Hildebrand, F. B. (1974). Introduction to Numerical Analysis (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-028761-9.

- Leader, Jeffery J. (2004). Numerical Analysis and Scientific Computation. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-73499-0.

- Wilkinson, J.H. (1965). The Algebraic Eigenvalue Problem. Clarendon Press.

- Kahan, W. (1972). A survey of error-analysis. Proc. IFIP Congress 71 in Ljubljana. Info. Processing 71. 2. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing. pp. 1214–39. (examples of the importance of accurate arithmetic).

- Trefethen, Lloyd N. (2006). "Numerical analysis", 20 pages. In: Timothy Gowers and June Barrow-Green (editors), Princeton Companion of Mathematics, Princeton University Press.

External links[]

Journals[]

- gdz.sub.uni-goettingen, Numerische Mathematik, volumes 1-66, Springer, 1959-1994 (searchable; pages are images). (in English and German)

- Numerische Mathematik, volumes 1–112, Springer, 1959–2009

- , volumes 1-47, SIAM, 1964–2009

Online texts[]

- "Numerical analysis", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Numerical Recipes, William H. Press (free, downloadable previous editions)

- First Steps in Numerical Analysis (archived), R.J.Hosking, S.Joe, D.C.Joyce, and J.C.Turner

- CSEP (Computational Science Education Project), U.S. Department of Energy (archived 2017-08-01)

- Numerical Methods, ch 3. in the Digital Library of Mathematical Functions

Online course material[]

- Numerical Methods Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Stuart Dalziel University of Cambridge

- Lectures on Numerical Analysis, Dennis Deturck and Herbert S. Wilf University of Pennsylvania

- Numerical methods, John D. Fenton University of Karlsruhe

- Numerical Methods for Physicists, Anthony O’Hare Oxford University

- Lectures in Numerical Analysis (archived), R. Radok Mahidol University

- Introduction to Numerical Analysis for Engineering, Henrik Schmidt Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Numerical Analysis for Engineering, D. W. Harder University of Waterloo

- Numerical analysis

- Mathematical physics

- Computational science