Oakdale Memorial Gardens

Entrance Gates | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1856 |

| Location | 2501 Eastern Ave. Davenport, Iowa |

| Country | United States |

| Type | Independent |

| Owned by | Oakdale Memorial Gardens |

| Size | 78 acres (32 ha) |

| No. of graves | over 24,000 |

| Website | Official website |

| Find a Grave | Oakdale Memorial Gardens |

| The Political Graveyard | Oakdale Memorial Gardens |

Oakdale Cemetery Historic District | |

| |

| Coordinates | 41°32′48″N 90°32′57″W / 41.54667°N 90.54917°WCoordinates: 41°32′48″N 90°32′57″W / 41.54667°N 90.54917°W |

| Architect | George F. de la Roche A. N. Carpenter Clausen & Kruse Israel Hall Edward Hammatt W. H. Kimball Robert H. Nott John W. Ross Seth J. Temple Nathaniel Tunnicliff Philip Tunnicliff Raymond C. Whitaker |

| Architectural style | Art Nouveau Egyptian Revival Gothic Revival Modern Neoclassical Romanesque Revival Richardsonian Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 15000194[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 5, 2015 |

| Designated DRHP | November 25, 2015[2] |

Oakdale Memorial Gardens, formerly Oakdale Cemetery, is located in east-central Davenport, Iowa, United States. It contains a section for the burial of pets called the Love of Animals Petland. In 2015, the cemetery was listed as an historic district on the National Register of Historic Places, and as a local landmark on the Davenport Register of Historic Properties.[3] It is also listed on the Network to Freedom, a National Park Service registry for sites associated with the Underground Railroad.[4]

History[]

Oakdale was established as a non-profit cemetery by a group of Davenport businessmen as an alternative to the overcrowded Davenport City Cemetery and the for-profit Pine Hill Cemetery.[5] It was incorporated as the Oakdale Cemetery Company May 14, 1856. The cemetery board hired Captain George F. de la Roche, who had finished the design of Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. five years earlier, to complete the design and platting of the cemetery.[5][6] It was designed as a rural or garden cemetery, but it transitioned to a landscape-lawn cemetery beginning in the late 19th century.[7] It covers more than 78 acres (32 ha).[8] The first numbered burial at Oakdale was that of three-month-old Mary Larned Allen on September 15, 1857, though several earlier burials were recorded at a later date, some from as early as October, 1855.[9] Some of the graves in the cemetery had been transferred from the overcrowded City Cemetery in the west end. The cemetery is located across Eastern Avenue from the former Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home, and it contains the graves of the orphans that died at the home. There are also at least 11 graves of former slaves who escaped to freedom by way of the Underground Railroad, which led to its inclusion on the Network to Freedom.[10]

Two special receiving vaults were built in the cemetery, although neither exists anymore. A brick vault was constructed in 1873 for those who died in the winter when the ground was frozen. A wooden vault was built next to it in 1918 because of the large number of deaths as a result of the Spanish flu epidemic.[9]

Architecture[]

The cemetery entrance is marked by a set of monumental gates, designed in the Art Nouveau style by Davenport architect Edward Hammatt in 1895. Construction of the gates was completed in 1896.[11]

The cemetery is also home to several private mausoleums. William D. Petersen was the son of J.H.C. Petersen who founded a department store in Davenport that has become Von Maur. He also was responsible for the development of the city's riverfront and built the LeClaire Park Bandshell there. His mausoleum was designed in the Gothic Revival style by Davenport architects Rudolph Clausen & Walter Kruse. It was inspired by his wife Sara's desire for a tomb similar to the ones she saw in Europe. It was constructed by Presbrey Leland of Valhalla, New York in 1921 for $60,000.[12] The exterior is composed of limestone from Greece. The interior features crypts that were carved from Greek marble and a ceramic tile ceiling that was designed and completed by the Guastavino Tile Company of Woburn, Massachusetts.

Joseph W. Bettendorf was an industrialist for whom the city of Bettendorf, Iowa is named. His mausoleum was built in 1923 in the Egyptian Revival style for $150,000.[12] Its exterior is composed of Barre Granite from Vermont. The interior features crypts carved from white marble and Egyptian-inspired stained glass windows.

The mausoleum built for Johannna Schricker, widow of Davenport lumber magnate Lorenzo Schricker, was designed in the Neoclassical style by Davenport architect John W. Ross. It was built by the Vermont Marble Company in 1899 at a cost of $6,489. The inspiration for the structure was the North Portico of the White House in Washington, D.C.[12] Its exterior is composed of Sutherland Falls white marble and features a bronze roof supplied by the Winslow Brothers of Chicago.

W.D. Petersen mausoleum

Bettendorf mausoleum

J. Schricker mausoleum

Brandt mausoleum

Gardiner mausoleum

Hartwig vault

Hill mausoleum

Koehler mausoleum

Nott mausoleum

H.F. Petersen mausoleum

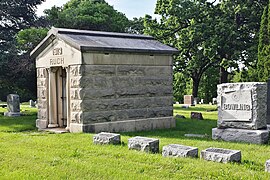

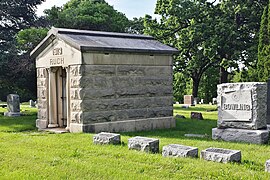

Ruch mausoleum

Schlapp columbarium

Sieg mausoleum

Wilson mausoleum

Soldiers' Lot[]

There is a Soldiers' Lot near the center of the cemetery,[13] which is administered by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.[14] At one time 174 soldiers were buried at Oakdale, including the first Iowans to die in the Civil War at the Battle of Fort Donelson.[15] Most of the bodies were transferred in 1888 to Rock Island National Cemetery or Keokuk National Cemetery. The remaining 14 soldiers' graves were moved to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) plot in 1900. The plot was transferred from the GAR to the cemetery association in 1940 and the United States government took possession of it the following year. Today it contains the remains of 71 soldiers from the Civil War and Spanish–American War.[15]

Notable burials[]

- Alfred T. Andreas (1839–1900), book publisher and historian

- Bix Beiderbecke (1903–1931) jazz musician

- Joseph W. Bettendorf (1864–1933), co-founder of the Bettendorf Axel Company with his brother; Bettendorf, Iowa is named after him

- William P. Bettendorf (1857–1910), inventor and co-founder of the Bettendorf Axel Company with his brother; Bettendorf, Iowa is named after him

- Henry Peter Bosse (1844–1903), photographer, cartographer and civil engineer

- Alice Braunlich (1888–1989), professor and classical philologist

- Frederick G. Clausen (1848–1940), architect; founder of oldest architectural firm in continuous existence in the state of Iowa

- Rudolph J. Clausen (1878–1961), architect; son and partner of Frederick G. Clausen

- John Parsons Cook (1817–1872), U.S. House of Representatives, 1853–1855

- Eloise Blaine Cram (1896–1957), zoologist and parasitologist

- George Henry Cram (1838–1872), American Civil War Brevet Brigadier General

- Ralph W. Cram (1869–1952), newspaper editor and aviator

- Edward Savage Crossett (1828–1910), lumber baron

- John Forrest Dillon (1831–1914), Jurist who authored a judicial treatise that is now referred to as "Dillon's Law."

- Nicholas Fejérváry (1811–1895) Hungarian nobleman

- Alice French (1850–1934), author who wrote under the pseudonym Octave Thanet

- James Grant (1812–1891), first president of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad, Speaker of the Iowa House of Representatives

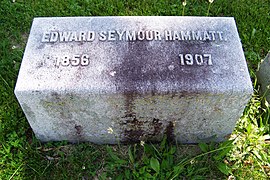

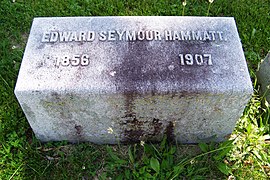

- Edward Hammatt (1856–1907), architect

- Rebecca J. Keck (1838–1904), physician and patent medicine entrepreneur

- Joseph R. Lane (1858–1931), U.S. House of Representatives, 1899–1901

- Joseph Bloomfield Leake (1828–1918), American Civil War Brevet Brigadier General

- Henry Washington Lee (1815–1874), first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Iowa 1854–1874

- John Fremont McCullough (1871–1963), co-founded Dairy Queen

- Paul Norton (1909–1984), watercolor artist

- Ernest Carl Oberholtzer (1884–1977), explorer, author and conservationist

- Dr. Charles Christopher Parry (1823–1890), botanist and mountaineer

- Hiram Price (1814–1901), U.S. House of Representatives, 1863–1869, 1877–1881; U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1881–1885

- John W. Ross (1830–1914), architect

- Addison Hiatt Sanders (1823–1912), American Civil War Brevet Brigadier General

- Phebe Sudlow (1831–1922), first female public school superintendent in the United States; first female professor at the University of Iowa

- James Thorington (1816–1887), U.S. House of Representatives, 1855–1857; Consul at Aspinwall, Colombia, 1873–1882

- John Vale (1835–1909), American Civil War Medal of Honor recipient

- Charles J. von Maur (1863–1926), department store chain co-founder

Alfred T. Andreas

Bix Beiderbecke

Joseph W. Bettendorf

William P. Bettendorf

Henry Peter Bosse

Parke T. Burrows

Clarissa and Ebenezer Cook

Edward Savage Crossett

Edward Hammatt

Bishop Henry Washington Lee

Charles Christopher Parry

Hiram Price

Phebe Sudlow

John Vale

Von Maur family

References[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Historic Preservation Commission. "Davenport Register of Historic Properties" (PDF). City of Davenport. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ "November 24, 2015 City Council Meeting Minutes". City of Davenport, Iowa. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ "Freedom Trail". Oakdale Memorial Gardens, Inc. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Burrows, John McDowell (1888). Fifty Years In Iowa. Davenport, Iowa: Glass & Company, Printers and Binders. pp. 152–154. ISBN 9780598280688. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ "Davenport Cemeteries". Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Doug Schorpp (May 24, 2014). "Oakdale volunteer tries to get cemetery on registry list". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Oakdale Memorial Gardens". Oakdale Memorial Gardens. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Oakdale Cemetery Historic District nomination form" (PDF). National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Program. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ Alma Gaul (June 14, 2015). "Beyond the grave: Honoring our Quad-City cemetery history". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Doug Schorpp (June 2, 2014). "Entrance gates at Oakdale back in full swing". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c Dustin Oliver (May 24, 2014). "Noted Oakdale Architecture". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Oakdale Cemetery Soldiers' Lot 41°32′45″N 90°32′47″W / 41.54583°N 90.54639°W

- ^ "Soldiers Lot". Interment. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Oakdale Soldiers' Lot Davenport, Iowa". National Park Service. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oakdale Cemetery (Davenport, Iowa). |

- Official website

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. IA-2-A, "Oakdale Cemetery, Soldiers Lot, 2501 Eastern Avenue, Davenport, Scott County, IA", 6 photos, 1 photo caption page

- Oakdale Memorial Gardens at Find a Grave

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Oakdale Cemetery

- Geography of Davenport, Iowa

- Cemeteries in the Quad Cities

- Protected areas of Scott County, Iowa

- Historic American Landscapes Survey in Iowa

- National Register of Historic Places in Davenport, Iowa

- Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places in Iowa

- Historic districts in Davenport, Iowa

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Iowa

- Davenport Register of Historic Properties

- United States national cemeteries