Old Malayalam

| Old Malayalam | |

|---|---|

| പഴയ മലയാളം | |

Old Malayalam (Vattezhuthu script) | |

| Pronunciation | Paḻaya Malayāḷam |

| Region | Kerala |

| Era | Developed into Middle Malayalam by c. 13th century |

Language family | Dravidian

|

Writing system | Vatteluttu script (with Pallava/Southern Grantha characters) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Old Malayalam, inscriptional language found in Kerala from c. 9th to c. 13th century AD,[1] is the earliest attested form of Malayalam.[2][3] The language was employed in several official records and transactions (at the level of the Chera Perumal kings as well as the upper-caste village temples).[2] Old Malayalam was mostly written in Vatteluttu script (with Pallava/Southern Grantha characters).[2] Most of the inscriptions were found from the northern districts of Kerala, those lie adjacent to Tulu Nadu.[2] The origin of Malayalam calendar dates back to year 825 CE.[4][5][6]

The existence of Old Malayalam is sometimes disputed by scholars.[7] They regard the Chera Perumal inscriptional language as a diverging dialect or variety of contemporary Tamil.[7]

History[]

The start of the development of Old Malayalam from a western dialect of contemporary Tamil can be dated to c. 7th - 8th century AD.[8][9][10] It remained a west coast dialect until c. 9th century AD or a little later.[11][8]

The formation of the language is mainly attributed to geographical separation of Kerala from the Tamil country[11] and the influence of immigrant Tulu-Canarese Brahmins in Kerala (who also knew Sanskrit and Prakrit).[2] Old Malayalam was called "Tamil" by the people of south India for many centuries.[12]

The later evolution of Old Malayalam is visible in the inscriptions dated to c. 9th to c. 12th century AD.[13][14]

Differences from contemporary Tamil[]

Although Old Malayalam closely resembles contemporary Tamil it also shows characteristic new features.[15] Major differences between Old Malayalam (the Chera Perumal inscriptional language) and contemporary inscriptional/literary Tamil of the Tamil country are[2]

- Nasalisation of adjoining sounds

- Substitution of palatal sounds for dental sounds

- Contraction of vowels

- Rejection of gender verbs

Old Malayalam was at first mistakenly described by scholars as "Tamil", then as "the western dialect of Tamil" or "mala-nattu Tamil" (a "desya-bhasa").[2][16]

Literary compositions[]

There is no Old Malayalam literature preserved from this period (c. 9th to c. 12th century AD).[7] Some of the earliest Malayalam literary compositions appear after this period.[13][14]

These include the Bhasa Kautiliya, the Ramacaritam, and the Thirunizhalmala.[17] The Bhasa Kautiliya is generally dated to a period after 11th century AD.[2] Ramacaritam, which was written by certain Ciramakavi who, according to poet Ulloor S. P. Iyer, was Sri Virarama Varman.[17] However the claim that it was written in Southern Kerala is expired on the basis of modern discoveries.[18] Other experts, like Chirakkal T Balakrishnan Nair, Dr. K.M. George, M. M. Purushothaman Nair, and P.V. Krishnan Nair, state that the origin of the book is in Kasaragod district in North Malabar region.[18] They cite the use of certain words in the book and also the fact that the manuscript of the book was recovered from Nileshwaram in North Malabar.[19] The influence of Ramacharitam is mostly seen in the contemporary literary works of Northern Kerala.[18] The words used in Ramacharitam such as Nade (Mumbe), Innum (Iniyum), Ninna (Ninne), Chaaduka (Eriyuka) are special features of the dialect spoken in North Malabar (Kasaragod-Kannur region).[18] Furthermore, the Thiruvananthapuram mentioned in Ramacharitham is not the Thiruvananthapuram in Southern Kerala.[18] But it is Ananthapura Lake Temple of Kumbla in the northernmost Kasaragod district of Kerala.[18] The word Thiru is used just by the meaning Honoured.[18] Today it is widely accepted that Ramacharitham was written somewhere in North Malabar (most likely near Kasaragod).[18] Ramacaritam is regarded as "the first literary work in Malayalam".[11] According to Hermann Gundert, who compiled the first dictionary of the Malayalam language, Ramacaritam shows the 'ancient style' of the Malayalam language.[20]

Folk Songs[]

For the first 600 years of the Malayalam calendar, Malayalam literature remained in a preliminary stage. During this time, Malayalam literature consisted mainly of various genres of songs (Pattu).[21] Folk songs are the oldest literary form in Malayalam.[22] They were just oral songs.[22] Many of them were related to agricultural activities, including Pulayar Pattu, Pulluvan Pattu, Njattu Pattu, Koythu Pattu, etc.[22] Other Ballads of Folk Song period include the Vadakkan Pattukal (Northern songs) in North Malabar region and the Thekkan Pattukal (Southern songs) in Southern Travancore.[22] Some of the earliest Mappila songs (Muslim songs) were also folk songs.[22]

Old Malayalam inscriptions[]

Old Malayalam was an inscriptional language.[23] No literary works in Old Malayalam have been found so far with the possible exceptions such as Ramacharitam and Thirunizhalmala.[7] Some of the discovered inscriptions in Old Malayalam are listed below on the basis of their expected chronological order, also including their locations and key contents.[23] Most of them are written in a mixture of Vatteluttu and Grantha scripts.[23]

| Inscription | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quilon Syrian copper plates- near Kollam (849/850 CE)[23] |

|

|

| Vazhappally copper plate Inscription - near Vazhappally (882/883 CE)[25] | ||

| Sukapuram inscription - near Ponnani (9th/10th century CE)[23] |

|

|

| Chokkur inscription (Chokoor, Puthur village) - near Koduvally (920 CE) |

|

|

| Nedumpuram Thali inscription, Thichoor Wadakkanchery (922 CE) |

|

|

| Avittathur inscription (925 CE) |

|

|

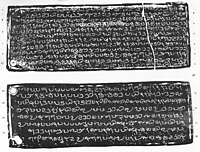

| Ramanthali/Ezhimala-Narayankannur inscription (Plate I - 929 CE and Plate II - 1075 CE) |

| |

| Triprangode inscription (932 CE) |

|

|

| Poranghattiri inscription (Chaliyar) (932 CE) |

|

|

| Indianur inscription (Kottakkal) (932 CE) |

|

|

| Thrippunithura inscription (935 CE) |

|

|

| Panthalayani Kollam inscription (973 CE) |

|

|

| Mampalli copper plate inscription (974 CE) |

|

|

| Koyilandy Jumu'ah Mosque inscription (10th century CE) |

|

|

| Eramam inscription (1020 CE) | ||

| Pullur Kodavalam inscription (1020 CE) |

|

|

| Tiruvadur inscription (c. 1020 CE) | ||

| Trichambaram inscription

(c. 1040 CE) |

|

|

| Maniyur inscription

(c. 11th century) |

|

|

| Kinalur inscription

(c. 1083 CE) |

| |

| Panthalayani Kollam inscription

(c. 1089 CE) |

||

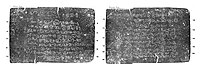

| Tiruvalla Copper Plates

(Huzur Treasury Plates) (10th-11th centuries CE) |

|

|

| Kannapuram inscription

(beginning of the 12th century) |

|

|

| Muchundi Mosque inscription (Kozhikode)

(beginning of the 13th century) |

|

|

| Viraraghava copper plates inscription

(1225 CE)[49] |

|

|

Old Malayalam epigraphic records[]

Maniyur inscription

Muchundi Mosque inscription (Kozhikode)

Vazhappally copper plate (Rama Rajasekhara)

Quilon Syrian copper plates (Sthanu Ravi Kulasekhara)

Quilon Syrian copper plates (plates 1 and 4)

Quilon Syrian copper plates (plate 6)

Tiruvalla copper plates

Perunna inscription (Rama Kulasekhara)

Viraraghava copper plates (Viraraghava)

Mampalli copper plate (Srivallabhan Kotha)

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g M. G. S. Narayanan. "Kozhikkodinte Katha". Malayalam/Essays. Mathrubhumi Books. Second Edition (2017) ISBN 978-81-8267-114-0

- ^ a b c d e f g h Narayanan, M. G. S. (2013). Perumals of Kerala. Thrissur: CosmoBooks. pp. 380–82. ISBN 9788188765072.

- ^ Ayyar, L. V. Ramaswami (1936). The Evolution of Malayalam Morphology (1st ed.). Trichur: Rama Varma Research Institute. p. 3.

- ^ "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218

- ^ R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Rich (2003). "The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". In Sheldon, Pollock (ed.). Literary Cultures in History. University of California Press. pp. 445–46.

- ^ a b Karashima, Noburu, ed. (2014). A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 152–53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 438-42.

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. "Malayalam language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. "Encyclopædia Britannica".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sheldon, Pollock (2003). "Introduction". Literary Cultures in History. University of California Press. p. 24.

- ^ a b Menon, T. K. Krishna (1939). A Primer of Malayalam Literature. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120606036.

- ^ a b Baby, Saumya (2007). L. V. Ramaswami Aiyar's Contributions to Malayalam Linguistics: A Critical Analysis (PDF). Department of Malayalam, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. (1972). Cultural Symbiosis in Kerala. Kerala: Kerala Historical Society. p. 18.

- ^ Veluthat, Kesavan (2018). "History and Historiography in Constituting a Region: The Case of Kerala". Studies in People's History. 5 (1): 13–31. doi:10.1177/2348448918759852. ISSN 2348-4489. S2CID 166060066.

- ^ a b Aiyer, Ulloor S. Parameshwara (1990). Kerala Sahitya Caritram. Trivandrum: University of Kerala.

- ^ a b c d e f g h [1]

- ^ Leelavathi, Dr. M., Malayala Kavitha Sahithya Chrithram (History of Malayalam poetry)

- ^ Gundert, Hermann (1865). Malayalabhasha Vyakaranam.

- ^ Dr. K. Ayyappa Panicker (2006). A Short History of Malayalam Literature. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Information and Public Relations, Kerala.

- ^ a b c d e Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019 (Malayalam Edition). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode. 2018. p. 453.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Narayanan, M. G. S. (2013) [1972]. Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks. ISBN 9788188765072.

- ^ a b Cereti, C. G. (2009). "The Pahlavi Signatures on the Quilon Copper Plates". In Sundermann, W.; Hintze, A.; de Blois, F. (eds.). Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447059374.

- ^ Devadevan, Manu V. (2020). "Changes in Land Relations and the Changing Fortunes of the Cēra State". The 'Early Medieval' Origins of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781108494571.

- ^ Rao, T. A. Gopinatha. Travancore Archaeological Series (Volume II, Part II). 8-14.

- ^ a b c d Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 435.

- ^ 'Changes in Land Relations during the Decline of the Cera State,' In Kesavan Veluthat and Donald R. Davis Jr. (eds), Irreverent History: Essays for M.G.S. Narayanan, Primus Books, New Delhi, 2014. 74-75.

- ^ a b c d Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 475-76.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 483.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 475-76.

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 448-49.

- ^ a b c Narayanan, M. G. S. 2013. 'Index to Chera Inscriptions', in Perumāḷs of Kerala, M. G. S Narayanan, pp. 218 and 478–79. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks.

- ^ Rao, T. A. Gopinatha. 1907-08 (1981 reprint). Mamballi Plates of Srivallavangodai', in Epigraphica Indica, Vol IX. pp. 234–39. Calcutta. Govt of India.

- ^ a b c Aiyer, K. V. Subrahmanya (ed.), South Indian Inscriptions. VIII, no. 162, Madras: Govt of India, Central Publication Branch, Calcutta, 1932. p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 455.

- ^ Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy (1963-64), No. 125.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 68-70, 84 and 454.

- ^ Narayanan, M.G.S. THE IDENTITY AND DATE OF KING MANUKULĀDITYA. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 31, 1969, 73–78.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 68-70, 84 and 454.

- ^ a b Narayanan, M.G.S. THE IDENTITY AND DATE OF KING MANUKULĀDITYA. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 31, 1969, 73–78.

- ^ a b c d Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 480-81.

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 465.

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 486.

- ^ a b c d e f Narayanan, M. G. S. 2013. 'Index to Chera Inscriptions', in Perumāḷs of Kerala, M. G. S Narayanan, pp. 484–85. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks.

- ^ a b c d Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 470.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 197.

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 483.

- ^ Veluthat, Kesavan. The Early Medieval in South India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2009. 152, and 154.

- ^ Epigraphica Indica, Volume IV. [V. Venkayya, 1896-97] pp. 290-7.

- ^ Epigraphica Indica, Volume IV. [V. Venkayya, 1896-97] pp. 290-7.

- ^ a b c Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 222, 279, and 299.

Further reading[]

- Dr. K. Ayyappa Panicker (2006). A Short History of Malayalam Literature. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Information and Public Relations, Kerala.

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019 (Malayalam Edition). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode. 2018.

- Malayalam language

- Dravidian languages