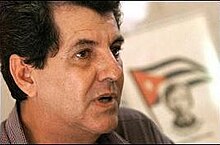

Oswaldo Payá

Oswaldo Payá | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas 29 February 1952 Cerro, Havana, Cuba |

| Died | 22 July 2012 (aged 60) Bayamo, Granma Province, Cuba |

| Cause of death | Disputed |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Organization | Christian Liberation Movement |

| Known for | Varela Project, opposition to Cuban Communist Party |

| Spouse(s) | Ofelia Acevedo |

| Children | Oswaldo José, Rosa María, and Reinaldo Isaías |

| Awards | Homo Homini Award (1999) Sakharov Prize (2002) |

Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas (29 February 1952 – 22 July 2012) was a Cuban political activist. A Roman Catholic, he founded the Christian Liberation Movement in 1987 to oppose the one-party rule of the Cuban Communist Party. He attracted international attention for organizing a petition drive known as the Varela Project, in which 25,000 signatories petitioned the Cuban government to guarantee freedom of speech and freedom of assembly as well as to institute a multi-party democracy. In recognition of his work, he received the European Parliament's Sakharov Prize and People in Need's Homo Homini Award.

On 22 July 2012, he died in a car crash under controversial circumstances. The Cuban government stated that the driver had lost control of the vehicle and collided with a tree, while Payá's children and one of the car's passengers asserted that the car had been deliberately run off of the road.

Early life[]

Oswaldo Payá was born on 29 February 1952 in Cerro, Havana.[1] The fifth of seven children, he was brought up as a Roman Catholic[2] and attended a Marist Brothers school in Havana.[3] Payá was the only student at the school who refused to join the Communist League following the Cuban Revolution.[4] The school was later closed.[5] In 1969, he was sentenced to three years of hard labor on Isla de Pinos when he refused to transport political prisoners during his mandatory military service.[6][7] While there, he discovered a locked Catholic church, Nuestra Señora de Dolores, that received permission from the Bishop of Havana to reopen as a mission, giving religious talks and caring for the sick.[4]

After his release, Payá enrolled in the University of Havana as a physics major, but was expelled when authorities discovered him to be a practicing Christian; he then attended night school and switched his major to telecommunications.[5] Payá later became an engineer and worked at a state surgical-equipment company.[2] He was offered an opportunity to leave Cuba in the 1980 Mariel boatlift, but chose to remain in Cuba and work for change.[4] He married Ofelia Acevedo in 1986 in a Catholic wedding.[5] The pair had three children: Oswaldo José, Rosa María, and Reinaldo Isaías.[7]

Career[]

Varela Project[]

In 1987, Payá founded the Christian Liberation Movement (MCL), which called for nonviolent civil disobedience against the rule of the Cuban Communist Party.[1][2] The group advocates for civil liberties and freedom for political prisoners.[8] He also began a magazine for Catholics titled People of God (Pueblo de Dios), calling for Christians to lead the struggle for human rights. However, the magazine was shut down the following year by Cuba's bishops under government pressure. Payá attempted to run for the National Assembly of People's Power (NAPP) in 1992, but was not allowed to stand.[4]

In the late 1990s, Payá and other MCL activists began collecting signatures for the Varela Project, a petition drive that would become his best-known program. Named in honor of Félix Varela, a Catholic priest who had participated in Cuba's independence struggle with Spain,[3] the Project took advantage of a clause in the Cuban Constitution requiring a national referendum to be held if 11,000 signatures are gathered.[9]

In May 2002, Payá presented NAPP with 11,020 signatures calling for a referendum on safeguarding freedom of speech and assembly,[10] allowing private business ownership,[11] and ending one-party rule.[6] On 3 October 2003, he delivered an additional 14,000 signatures.[12] Former U.S. president Jimmy Carter endorsed the petition when granted a chance to speak on Cuban television, bringing Payá's efforts to the attention of a wide Cuban audience.[13] Cuban President Fidel Castro described the petition drive as a U.S.-backed conspiracy to overthrow his government.[14]

According to the Los Angeles Times, the petition drive was "the biggest nonviolent campaign to change the system the elder Castro established after the 1959 Cuban revolution", giving Payá an international reputation as a leading dissident.[2] An expert described it as "the only initiative of its time that enlisted citizen participation on a large scale".[10] Fellow dissident Rene Gomez Manzano, on the other hand, was critical of the Project, stating that appeals to the Communist-Party-controlled NAPP were futile;[15] similarly, other Cuban exiles criticized the initiative for what they considered its implicit acceptance of the legitimacy of the Castro regime and its constitution.[16]

Later that year, Payá's efforts were recognized by the European Parliament, which awarded him its Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought,[10] although he was nearly denied an exit visa to attend the awards ceremony.[11] In the months that followed, Payá met with Pope John Paul II, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, and Mexican President Vicente Fox to discuss the cause of Cuban democratic reform.[17] The Varela Project progress was blocked when the government launched its own petition drive to declare the socialist state "irrevocable".[10] During the 2003 crackdown popularly known as the Black Spring, MCL members comprised around 40 of the 75 defendants, though Payá himself was not arrested.[18]

Later activism[]

During Castro's illness, which culminated in his 2008 resignation, Payá continued to criticize the Cuban government as it transferred power to Castro's brother Raúl.[2] He called on Raul Castro to allow multiparty elections and free all political prisoners,[19] and delivered a petition asking that the Cuban people be granted freedom of travel.[20]

In the years before Payá's death, his influence was said to be waning, and attention shifted to younger activists such as blogger Yoani Sanchez.[6] In 2010, WikiLeaks released U.S. State Department cables from Jonathan D. Farrar, head of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, describing Payá and other older dissidents as "hopelessly out of touch", writing, "They have little contact with younger Cubans and, to the extent they have a message that is getting out, it does not appeal to that segment of society."[5][21] However, many of the younger generation of dissidents cited him as a role model and expressed grief at his death.[10]

Political views[]

Opposition to United States groups and policy[]

Payá refused to accept U.S. aid and also opposed the U.S. Cuban embargo.[3] In a 2000 editorial for the Miami Herald, he stated that "Lifting the embargo won't solve the problems of the Cuban people. Maintaining it is no solution, either". He called on the U.S. to immediately lift the embargo on food and medicine.[22]

He also maintained his distance from Cuban political groups based in the U.S.[3] In particular, he refused to support their stated goal of land reacquisition upon the return of exiles to Cuba:

- "It is not a neoliberal programme. For this, we are under attack by the powerful groups in Miami. When people say what is going to happen in Cuba after Fidel, we say – hold on, there are 11 million people in Cuba, not only Fidel Castro."[23]

Opposition to government cooperation[]

In 2005, he also feuded with democracy activist Marta Beatriz Roque, accusing her of collaborating with security forces to provide justification for a further crackdown.[24] Although his political activity was tolerated and on a few occasions he was allowed to travel abroad, Payá reported that both he and his family were subject to routine intimidation: "I have been told that I am going to be killed before the regime is over but I am not going to run away."[23]

Death[]

Payá died in a car crash on 22 July 2012 at the age of 60. The incident occurred at 1:50 p.m. near Bayamo in eastern Granma province, according to a statement released by the Cuban government's International Press Center. The chairman of the MCL's youth league, Harold Cepero, also died in the crash.[8][25] Swedish politician and chairman of the Young Christian Democrats Aron Modig and Spanish politician Ángel Carromero Barrios were present, but survived with minor injuries.[18][26][27] All four were taken to Professor Carlos Manuel Clinical Surgery Hospital in Bayamo, though Payá was dead on arrival.[7] The car was driven by Carromero, well known in his country through his numerous but minor violations of traffic laws.[28] In late February 2014, the High Court of Spain upheld the decision of Judge Eloy Velasco, taken in September 2013, not to accept the complaint filed by the family of Oswaldo Payá against two senior Cuban military officers for the death of Payá. Carromero went on trial in Cuba, where he was convicted of non-planned murder.

At a press conference arranged by Cuban authorities on 30 July, Modig and Carromero stated that the crash was an accident and no other car was involved.[29][30] Speaking in 2013 to the Washington Post, Carromero denied this version of events, stating that he had been drugged and threatened by Cuban authorities who had forced him to make a false statement. He stated instead that the car had been rammed by another vehicle with Cuban government license plates, causing the fatal crash.[31]

Payá's daughter Rosa María stated that her father died after the rental car in which he was traveling was rammed several times by another car.[32] Payá's son Oswaldo added that his father had received numerous death threats and stated that the accident's survivors had reported that the car had been deliberately driven off the road.[8][33] The official statement by the Cuban government stated that the driver lost control of the vehicle and collided with a tree.[8][25] The MCL stated that "the circumstances of these deaths have not been cleared up and are open to hypothesis" and demanded a "transparent" inquiry into the accident.[34] On 27 July, the Cuban Interior Ministry forwarded an official report to foreign press, blaming driver error and quoting Carromero as saying that the car had skidded off the road due to poor road conditions and bad weather.[35] Payá's widow rejected the report, stating that the crash was not an accident and that a government report could not be trusted.[36]

U.S. President Barack Obama released a statement praising Payá as "a tireless champion for greater civic and human rights in Cuba". U.S. Senator Marco Rubio and Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney called for an independent investigation into the crash, imploring the international community to "demand that the facts concerning Paya's death be accurately determined and that the surviving witnesses be protected".[37] The European Union issued a statement recognizing Payá's dedication "to the cause of democracy and human rights in Cuba".[38] Elizardo Sanchez, president of the Cuban Commission for Human Rights, stated that "This is tragic for the family and the human rights and pro-democracy movement in Cuba ... Payá was considered the most notable political leader of the Cuban opposition."[32] Ladies in White president Berta Soler described the death as "a terrible blow".[18]

Payá's funeral was held on 24 July 2012. Dissident groups reported that dozens of activists were arrested on their way to the funeral,[39] including Félix Navarro Rodríguez and Guillermo Fariñas.[40] A scuffle also broke out between activists and state security agents at the funeral itself. Amnesty International and the U.S. criticized the arrests, with the White House describing them as "a stark demonstration of the climate of repression in Cuba."[41] The dissidents arrested in Payá's funerals were freed the following day.[33]

Oswaldo Payá's daughter Rosa Maria has continued his activism for democratic reforms in Cuba.[42]

Awards and recognition[]

- The Homo Homini Award of People in Need, a Czech NGO, 1999[43]

- The Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought of the European Parliament, 2002[11]

- W. Averell Harriman Democracy Award from U.S. National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 2003[7]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Columbia University in New York, 2005[7]

- Nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the former Czech President Václav Havel, with fellow Cuban dissidents Raul Rivero and Óscar Elías Biscet[44]

See also[]

- Heinrich Maier

- Grigoris Lambrakis, Greek democratic activist who was assassinated in 1963 in the Kingdom of Greece (present-day Greece)

- Christian Democracy

- Censorship in Cuba

- Human rights in Cuba

References[]

- ^ a b "Acerca de Oswaldo" (in Spanish). oswaldopaya.org. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Oswaldo Paya dies at 60; Cuban anti-Castro activist". Los Angeles Times. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Mimi Whitefield (23 July 2012). "Oswaldo Payá, well-known Cuban dissident, killed in car crash on the island". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Philip Brenner (2008). A Contemporary Cuba Reader: Reinventing the Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 106–09. ISBN 978-0-7425-5507-5. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Cuban activist Oswaldo Paya dies in car crash, fellow dissidents say". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "Top Cuba dissident Oswaldo Paya 'killed in car crash'". BBC News. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Yoani Sanchez (23 July 2012). "Cuban Opposition Leader Oswaldo Payá Dies in Car Crash". Huffington Post. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Cuba dissident 'driven off road' to death, says family". BBC News. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ David Gonzalez (13 October 2002). "Cuba Can't Ignore a Dissident It Calls Insignificant". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Damien Cave (23 July 2012). "Oswaldo Payá, Cuban Leader of Petition Drive for Human Rights, Dies at 60". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "Cuban dissident collects EU prize". BBC News. 17 December 2002. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Stephen Gibbs (3 October 2003). "New petition for Cuba changes". BBC News. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Patrick Oppman (23 July 2012). "Details of crash that killed Cuban dissident disputed". CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuban dissident leader Oswaldo Paya dies in alleged accident". Catholic News Agency. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Fernando Ravensburg (23 July 2012). "Adiós al padre del mayor movimiento de disidencia interna en Cuba". BBC News (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Sánchez-Boudy, José (2005). El Exilio Histórico y la Fe en el Triunfo. Miami: Ediciones Universal.

- ^ David Gonzalez (18 January 2003). "Cuban Dissident Ends Tour Hopeful of Democratic Reform". New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Rosa Tania Valdes (24 July 2012). "Cuban dissidents gather to mourn Oswaldo Paya". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Emilio San Pedro (27 July 2007). "Cuban dissident in elections call". BBC News. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuban dissident calls for amnesty". BBC News. 19 September 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "US cable: Cuban opposition out of touch". Fox News Channel. Associated Press. 17 December 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Oswaldo Payá (14 August 2000). "What Do Cubans Want?". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b Duncan Campbell (4 August 2006). "The rocky road to change". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuba dissidents debate democracy". BBC News. 21 May 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Swedish youth politician injured in Cuba car crash". The Local. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Patrick Oppman (23 July 2012). "Cuban dissident dies in car accident". CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Var i Sverige flera gånger". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 23 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Modig kan lämna kuba". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 30 July 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Andrea Rodriquez (30 July 2012). "Survivors: No 2nd car in deadly Cuba car crash". Houston Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved 30 July 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "An eyewitness to Oswaldo Paya's death speaks out; The accident that killed Oswaldo Paya must be investigated and the truth exposed". The Washington Post. 5 March 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ a b Jonathan Watts (23 July 2012). "Cuban dissident Oswaldo Payá's death 'no accident', claims daughter". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Police free Cubans detained at Oswaldo Paya's funeral". BBC News. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Mimi Whitefield (23 July 2012). "Cuban dissidents call for 'transparent' investigation of Oswaldo Payá's death". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuba: Oswaldo Paya's accident caused by 'driver error'". BBC News. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuba: Wife of Oswaldo Paya says crash was no 'accident'". BBC News. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Romney Joins Call for Transparent Investigation into Oswaldo Paya's Death". Fox News Latino. Associated Press. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuban dissidents, foreign governments mourn activist Paya after deadly car crash". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Dozens reported arrested on way to Cuban dissident's funeral". CNN. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Cuba: Dozens arrested at funeral of prominent rights activist". Amnesty International. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "US, Amnesty Critical of Cuban Dissident Detentions". ABC News. Associated Press. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Oswaldo Paya's fight for a democratic Cuba lives on ; Daughter of activist carries his message forward". The Washington Post. 10 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ "Previous Recipients of the Homo Homini Award". People in Need. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Roisin Joyce (1 January 2005). "2005 Nobel Peace Prize nomination for Payá, Rivero and Biscet". International Committee for Democracy in Cuba. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

External links[]

- 1952 births

- 2012 deaths

- Cuban democracy activists

- Cuban dissidents

- Cuban human rights activists

- Cuban Roman Catholics

- Nonviolence advocates

- Opposition to Fidel Castro

- Road incident deaths in Cuba

- Cuban anti-abortion activists

- Cuban anti-communists

- Sakharov Prize laureates