Ottoman Algeria

Coordinates: 36°42′13.8″N 3°9′30.6″E / 36.703833°N 3.158500°E

It has been suggested that this article be split into a new article titled Deylik of Algiers. (Discuss) (January 2021) |

The Regency of Algiers الجزائر (Arabic) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |||||||||||||||||

![Flag of Algiers, Province of[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a3/Flag_of_Ottoman_Algiers.svg/125px-Flag_of_Ottoman_Algiers.svg.png) Flag[2]

![Coat of arms of Algiers, Province of[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Lesser_coat_of_arms_of_Regency_of_Algiers.svg/85px-Lesser_coat_of_arms_of_Regency_of_Algiers.svg.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||

![Map of the Regency of Algiers (in light blue) and all Barbary Coast in 1824[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Regency-of-Algiers-1824.jpg/300px-Regency-of-Algiers-1824.jpg) Map of the Regency of Algiers (in light blue) and all Barbary Coast in 1824[3] | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | See Political status | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Algiers | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (official, government, religious, literature), Berber, Ottoman Turkish (elite, diplomatic) | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Official, and majority: Sunni Islam (Maliki and Hanafi) Minorities: Ibadi Islam Shia Islam Judaism Christianity | ||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Algerian, or Algerine | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | 1516-1671 Governorate 1670-1710 Dual leadership 1710-1830 Elective Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Beylerbey, Pasha, Agha, Dey | |||||||||||||||||

• 1516-1518 | Oruç Reis | ||||||||||||||||

• 1710-1718 | Baba Ali Chaouch | ||||||||||||||||

• 1818-1830 | Hussein Dey | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1516 | ||||||||||||||||

• Invasion of Algiers in 1830 | 1830 | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1808 | 3,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Algeria | ||||||||||||||||

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

The Regency of Algiers[a] (Arabic: الجزائر, romanized: al Jaza'ir[b]) was a state in North Africa lasting from 1516 to 1830, until it was conquered by the French. Situated between the regency of Tunis in the east, the Sultanate of Morocco (from 1553) in the west and Tuat[12][13] as well as the country south of In Salah[14] in the south (and the Spanish and Portuguese possessions of North Africa), the Regency originally extended its borders from La Calle in the east to Trara in the west and from Algiers to Biskra,[15] and afterwards spread to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.[16]

It had various degrees of autonomy throughout its existence, in some cases reaching complete independence, recognized even by the Ottoman sultan.[17] The country was initially governed by governors appointed by the Ottoman sultan (1518–1659), rulers appointed by the Odjak of Algiers (1659–1710), and then Deys elected by the .

History[]

Establishment[]

From 1496, the Spanish conquered numerous possessions on the North African coast, which had been captured since 1496: Melilla (1496), Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Bougie (1510), Tripoli (1510), Algiers, Shershell, Dellys, and Tenes.[18] The Spaniards later led unsuccessful expeditions to take Algiers in the Algiers expedition in 1516, 1519 and another failed expedition in 1541.

Around the same time, the Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin—both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard"—were operating successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids. In 1516, Oruç moved his base of operations to Algiers and asked for the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1517, but was killed in 1518 during his invasion of the Kingdom of Tlemcen. Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers.[19]

In 1551 Hasan Pasha, the son of Hayreddin defeated the Spanish-Moroccan armies during the Campaign of Tlemcen, thus cementing Ottoman control in Western and Central Algeria.[20]

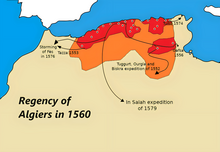

After that, the conquest of Algeria sped up. In 1552 Salah Rais, with the help of some Kabyle kingdoms conquered Touggourt, and established a foothold in the Sahara.[21]

In the 1560s Eastern Algeria was centralized, and the power struggle which had been present ever since the collapsed ended.

During the 16th, 17th, and early 18th century, the Kabyle Kingdoms of Kuku and Ait Abbas managed to maintain their independence[22][23][24] repelling Ottoman attacks several times, notably in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes. This was mainly thanks to their ideal position deep inside the Kabylia Mountains and their great organisation , and the fact that unlike in the West and East where collapsing kingdoms such as Tlemcen or Bejaia were present, Kabylia had 2 new and energetic emirates.

Base in the war against Spain[]

Hayreddin Barbarossa established the military basis of the regency. The Ottomans provided a supporting garrison of 2,000 Turkish troops with artillery.[25] He left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy when he had to leave for Constantinople in 1533.[26] The son of Barbarossa, Hasan Pashan was in 1544 when his father retired, the first governor of the Regency to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Empire. He took the title of beylerbey.[26] Algiers became a base in the war against Spain, and also in the Ottoman conflicts with Morocco.

Beylerbeys continued to be nominated for unlimited tenures until 1587. After Spain had sent an embassy to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate a truce, leading to a formal peace in August 1580, the Regency of Algiers was a formal Ottoman territory, rather than just a military base in the war against Spain.[26] At this time, the Ottoman Empire set up a regular Ottoman administration in Algiers and its dependencies, headed by Pashas, with 3-year terms to help considate Ottoman power in the Maghreb.

Mediterranean privateer[]

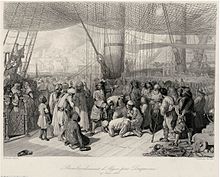

Despite the end of formal hostilities with Spain in 1580, attacks on Christian and especially Catholic shipping, with slavery for the captured, became prevalent in Algiers and were actually the main industry and source of revenues of the Regency.[27]

In the early 17th century, Algiers also became, along with other North African ports such as Tunis, one of the bases for Anglo-Turkish piracy. There were as many as 8,000 renegades in the city in 1634.[27][28] (Renegades were former Christians, sometimes fleeing the law, who voluntarily moved to Muslim territory and converted to Islam.) Hayreddin Barbarossa is credited with tearing down the Peñón of Algiers and using the stone to build the inner harbor.[29]

A contemporary letter states:

"The infinity of goods, merchandise jewels and treasure taken by our English pirates daily from Christians and carried to Allarach [ Larache, in Morocco], Algire and Tunis to the great enriching of Mores and Turks and impoverishing of Christians"

— Contemporary letter sent from Portugal to England.[30]

Privateer and slavery of Christians originating from Algiers were a major problem throughout the centuries, leading to regular punitive expeditions by European powers. Spain (1567, 1775, 1783), Denmark (1770), France (1661, 1665, 1682, 1683, 1688), England (1622, 1655, 1672), all led naval bombardments against Algiers.[27] Abraham Duquesne fought the Barbary pirates in 1681 and bombarded Algiers between 1682 and 1683, to help Christian captives.[31]

Political Turmoil (1659-1713)[]

The Agha period[]

In 1659 the Janissaries of the Odjak of Algiers took over the country, and removed the local Pasha with the blessing of the Ottoman Sultan. From there on a system of dual leaders was in place. There was first and foremost the Agha, elected by the Odjak, and the Pasha appointed by the Ottoman Sublime Porte, whom was a major cause of unrest.[32] Of course, this duality was not stable. All of the Aghas were assassinated, without an exception. Even the first Agha was killed after only 1 year of rule. Thanks to this the Pashas from Constantinople were able to increase the power, and reaffirm Turkish control over the region. In 1671, the Rais, the pirate captains, elected a new leader, . The Janissaries also supported him, and started calling him the Dey, which means Uncle in Turkish.[33]

Early Dey period (1671-1710)[]

In the early Dey period the country worked similarly to before, with the Pasha still holding considerable powers, but instead of the Janissaries electing their own leaders freely, other factions such as the Taifa of Rais also wanted to elect the deys. Mohammed Trik, taking over during a time instability was faced with heavy issues. Not only were the Janissaries on a rampage, removing any leaders for even the smallest mistakes (even if those leaders were elected by them), but the native populace was also restless. The conflicts with European powers didn't help this either. In 1677, following an explosion in Algiers and several attempts at his life, Mohammed escaped to Tripoli leaving Algiers to Baba Hassan.[34] Just 4 years into his rule he was already at war with one of the most powerful countries in Europe, the Kingdom of France. In 1682 France bombarded Algiers for the first time.[35] The Bombardment was inconclusive, and the leader of the fleet Abraham Duquesne failed to secure the submission of Algiers. The next year, Algiers was bombarded again, this time liberating a few slaves. Before a peace treaty could be signed though, Baba Hassan was deposed and killed by a Rais called Mezzo Morto Hüseyin.[36] Continuing the war against France , near Cherchell, and at last a French Bombardment in 1688 brought an end to his reign, and the war. His successor, was elected by the Raïs, he defeated Morocco in a war, and .[37] He went back to Algiers, but he was assassinated in 1695 by the Janissaries whom once again took over the country. From there on Algiers was in turmoil once again. Leaders were assassinated, despite not even ruling for a year, and the Pasha was still a cause of unrest. The only notable event during this time of unrest was the recapture of Oran and Mers-el-Kébir from the Spanish.

Coup of Baba Ali Chaouche, and independence[]

Baba Ali Chaouche, also written as Chaouch, took over the country, ending the rule of the Janissaries. The Pasha attempted to resist him, but instead he was sent home, and told to never come back, and if he did he will be executed. He also sent a letter to the Ottoman sultan declaring that Algiers will from then on act as an independent state, and will not be an Ottoman vassal, but an ally at best.[38] The Porte, enraged, tried to send another Pasha to Algiers, whom was then sent back to Constantinople by the Algerians. This marked the De facto independence of Algiers from the Ottoman Empire.[39]

Danish–Algerian War[]

In the mid-1700s Dano-Norwegian trade in the Mediterranean expanded. In order to protect the lucrative business against piracy, Denmark–Norway had secured a peace deal with the states of Barbary Coast. It involved paying an annual tribute to the individual rulers and additionally to the States.

In 1766, Algiers had a new ruler, dey Baba Mohammed ben-Osman. He demanded that the annual payment made by Denmark-Norway should be increased, and he should receive new gifts. Denmark–Norway refused the demands. Shortly after, Algerian pirates hijacked three Dano-Norwegian ships and allowed the crew to be sold as slaves.

They threatened to bombard the Algerian capital if the Algerians did not agree to a new peace deal on Danish terms. Algiers was not intimidated by the fleet, the fleet was of 2 frigates, 2 bomb galiot and 4 ship of the line.

Algerian-Sharifian War[]

In the west, the Algerian-Cherifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[40]

There were numerous battles between the Regency of Algiers and the Sharifian Empires for example: Campaign of Tlemcen (1551), Campaign of Tlemcen (1557), Battle of Moulouya and the Battle of Chelif. The independent Kabyle Kingdoms also had some involvement, the Kingdom of Beni Abbes participated in the Campaign of Tlemcen (1551) and the Kingdom of Kuku provided Zwawa troops for the Capture of Fez in which Abd al-Malik was installed as an Ottoman vassal ruler over the Saadi Dynasty.[41][42] The Kingdom of Kuku also participated in the Capture of Fez (1554) in which Salih Rais defeated the Moroccan army and conquered Morocco up until Fez, adding these territories to the Ottoman crown and placing Ali Abu Hassun as the ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[43][44][45] In 1792 the Regency of Algiers managed to take possession of the Moroccan Rif and Oujda, which they then abandoned in 1795 for unknown reasons.[46]

Barbary Wars[]

During the early 19th century, the Algiers again resorted to widespread piracy against shipping from Europe and the young United States of America, mainly due to internal fiscal difficulties, and the damage caused by the Napoleonic Wars.[27] This in turn led to the First Barbary War and Second Barbary Wars, which culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers, the biggest, and most successful one.[47] The Barbary Wars resulted in a major victory for the American, British, and Dutch Navy.

French invasion[]

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and of the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit by France. In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's ruler, demanded that the French pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 by purchasing supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt.

The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give answers satisfactory to the dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey hit the consul with his fan. Charles X used this as an excuse to break diplomatic relations. The Regency of Algiers would end with the French invasion of Algiers in 1830, followed by subsequent French rule for the next 132 years.[27]

Administration[]

Territorial management[]

The Regency was composed of various beyliks (provinces) under the authority of beys (vassals):

- The Beylik of Constantine in the east, with its capital in Constantine

- The Beylik of Titteri in the Centre, with its capital being Médéa or Mazouna

- The Beylik of the West, with its capital being Mascara and then Oran

Each beylik was divided into outan (counties) with at their head the caïds directly under the bey. To administer the interior of the country, the administration relied on the tribes called makhzen. These tribes were responsible for securing order and collecting taxes on the tributary regions of the country. It was through this system that, for three centuries, the State of Algiers extended its authority over the north of Algeria. However, society was still divided into tribes and dominated by maraboutic brotherhoods or local djouads (nobles). Several regions of the country thus only lightly recognised the authority of Algiers. Throughout its history, they formed numerous revolts, confederations, tribal fiefs or sultanates that fought with the regency for control. Before 1830, out of the 516 political units, a total of 200 principalities or tribes were considered independent because they controlled over 60% of the territory in Algeria and refused to pay taxes to Algiers.

Diwan[]

The was started in the 16th century by the . It was seated in the . This assembly, initially led by a Janissary Agha would soon go from a way to administer the Odjack to a central part of the country's administration.[48] This change started in the 17th century, and the Diwan became an important part of the state, albeit it was still dominated by the Janissaries. Around 1628 the Divan was expanded to include 2 subdivisions. One called the private (Janissary) Divan (diwan khass), and the Public, or Grand Diwan (diwan âm). The latter was composed of Hanafi scholars and preachers, the raïs, and native notables. It numbered between 800-1500 people, but it was still less important than the Private Divan used by the Janissaries. During the period when Algiers was ruled by Aghas, the leader of the Divan was also the leader of the country. The Agha called himself the Hakem.[49] In the 18th century, following the coup of Baba Ali Chaouche, the Divan was reformed. The grand divan was now the dominant one, and it was the main body of the government which elected the leader of the country, the Dey-Pacha. This new reformed Divan was composed of:

- Officials

- Ministers

- Tribal elders

- Moorish, Arab, and Berber Nobles

- Janissary commanders (Kouloughlis, and Turks)

- Rais (Pirate captains)

- Ulema

The Janissary Divan remained completely under the control of the Turkish Janissary commanders, albeit it lost all authority other than decisions in the affairs of Janissaries.

This Divan normally met once a week, albeit this wasn't always true, since if the Dey felt powerful enough he could simply stop the Divan's functions. At the beginning of their mandate, the deys consulted the divan on all important questions.[50]

However, as the Deys became stronger, the Divan became weaker. By the 19th century, the Divan was mostly ignored, especially the private Janissary Divan. The dey's council, (also called Divan by the British) became more and more powerful. Dey Ali Khodja weakened the Janissary Divan to the point where they held no power. This angered the Turkish Janissaries, who launched a coup against the Dey. The coup failed, since the Dey successfully raised an army of Kabyle Zwawa cavalry, Arab infantry and Kouloughli troops. Many of the Turkish Janissaries were executed, while the rest fled. The Janissary Divan was abolished, and the Grand Divan was moved to the citadel of the Casbah.

Armed forces[]

Levy warriors[]

The levy militia composed from Arab-Berber warriors numbered in the tens of thousands, being overwhelmingly the largest part of the Algerian army. They were called upon from loyal tribes and clans, usually Makhzen ones. They numbered up to 50,000 in the Beylik of Oran alone.[51] The troops were armed with muskets, usually moukahlas, and swords, usually either Nimchas or Flyssas, both of which were traditional local swords.[52][53] The weaponry wasn't supplied by the state, and instead it was self-supplied. As nearly every peasant and tribesman owned a musket, it was expected from the soldiers to be equipped with one. As many of these tribes were traditionally warrior ones, many of these troops were trained since childhood, and thus were relatively effective especially in swordsmanship, albeit they were hampered by their weak organization, and by the 19th century their muskets became outdated.[54]

Odjak of Algiers[]

The Odjak of Algiers was a faction in the country which encompassed all janissaries. They often also controlled the country, for example during the period of Aghas from 1659 to 1671.[26] They usually formed the main part of the army as one of the only regular unit they possessed.

The Odjak was initially mainly composed of foreigners[55] as local tribes were deemed unreliable and their allegiance would often shift. Thus Janissaries were used to patrol rural tribal areas, and to garrison smaller forts in important locations and settlements ().

With the emancipation of Algiers from direct Ottoman control, and the worsening of relations with the Ottoman porte, the Odjak of Algiers became much less prominent. From there on, they only numbered in the thousands.[56] A lot of the Janissaries, possibly the majority at some point albeit it is not clear, were recruited among Kouloughlis (mixed Algerian-Turks).[57] Despite the fact that previously all locals were barred from joining the Odjak, Arabs, Berbers, and Moors were allowed to join it after 1710, as a way to replenish the unit. In 1803, 1 in 17 troops of the Odjak were Arabs and Berbers,[58] and by 1830 the Odjak of Algiers possessed at least 2,000 native Algerian janissaries mainly from the Zwawa tribes.[59] According to historian about 10-15% of the Odjak was composed of native Algerians and renegades (not counting Kouloughlis).[60]

The exact size of the Odjak varied greatly, and they were usually divided into several hundred smaller units (ortas).[60] These units were mostly stationed in Algiers, Constantine, Mascara, Medea etc. although usually every town with a few thousand inhabitants had at least 1 orta stationed in it. Unlike the noubachis, regular units, and tribal levy, the Odjak had their own system of leadership, and they operated freely from the Beys and Deys.[60]

Spahis of Algiers[]

Not much is known about the Spahis of Algiers, other than the fact that they were a regular standing unit, and were mainly composed of locals (although there were Turks amongst them).[60] They differed greatly from the traditional Ottoman Sipahis, in both military equipment, and organization, and hardly had anything in common with them other than their names, and both being cavalry units. The Dey also periodically possessed several thousand spahis in his service acting as a personal guard.[61] Other than the Dey's guard, Spahis were not recruited or stationed in Algiers, instead being usually recruited by the Beys.[62] They were usually more organized than the irregular tribal cavalry, although far less numerous.

The French Spahi units were based on the Algerian spahis,[63] and they were both mainly light cavalry.

Modern style units[]

Algiers hardly possessed units based on Napoleonic or post-Napoleonic warfare, and many of their units, including the Odjak of Algiers were organized on outdated 17th and 18th century Ottoman standards. The only two main units which existed as Modern-style units were the small Zwawa guard established by Ali Khodja Dey in 1817 to counter-balance the influence of the Odjak, and the small army of Ahmed Bey ben Mohamed Chérif, the last Bey of Constantine, who organized his army on the lines of Muhammad Ali's Egyptian Army. Ahmed Bey's army was composed of 2,000 infantry, and 1,500 cavalry. His entire army was composed of native Algerians,[64] and he also built a complex system of manufactories to support the army and invited several foreigners to train technicians and other specialists.[65]

Corsairs[]

In 1625, Algiers' pirate fleet numbered 100 ships and employed 8,000 to 10,000 men. The piracy "industry" accounted for 25 percent of the workforce of the city, not counting other activities related directly to the port. The fleet averaged 25 ships in the 1680s, but these were larger vessels than had been used the 1620s, thus the fleet still employed some 7,000 men.[66]

Leadership, and commanders[]

Main units[]

The army was divided into 4 regions, the exact same regions as the administrational ones (Beyliks).

- Western Army, headed by the

- Central Army, headed by the

- Eastern Army, headed by the Bey of Constantine

- Dar as-Soltan army, headed by the Dey and the Agha.

These troops were headed by the Beys, and a Khalifa (general) appointed by them. Levying these troops was the job of the Bey. The Odjak was headed by an Agha elected by the Odjak itself. When Algiers came under attack, the Beyliks would send their troops to help the besieged city, such as in 1775 during the Spanish Invasion of Algiers.[67] As the Beys were regional commanders, they also fought the wars in their own region, occasionally reinforced by troops from the Dar as-Soltan army. For example in 1792, during the the Bey of Oran, (Bey of Oran) was the one to besiege the city using the army of the Beylik of the West, numbering up to 50,0000 with some additional reinforcements from Algiers. During the the Eastern army fought the war against the Tunisian armies. Its composition was 25,000 levy warriors from Constantine, and 5,000 reinforcements from Algiers.[68] Sub-commanders usually included powerful tribal Sheiks, djouads, or caids.

Command structure of the Odjak of Algiers[]

The command structure of the Odjak relied on several tiers of military commanders. Initially based on basic Janissary structures, after the 17th century it was slightly changed to better fit the local warfare styles and politics. The main ranks of the Odjak were:[60]

- Agha, or marshall of the Odjak. Elected by the Odjak until 1817, after which the Dey appointed the Aghas.[69]

- Aghabashi, which was equal to the rank of General in western armies

- Bulukbashi, or senior officer

- Odabashi, or officer

- Wakil al-Kharj, a non-commissioned officer or supply clerk

- Yoldash, or regular soldier

Economy[]

Monetary system[]

Initially using various forms of Ottoman and old Zayyanid and Hafsid coins such as the (a sub-unit of the Akçe), Algiers soon developed its own monetary system, minting its own coins in the Casbah of Algiers and Tlemcen.[70] The "central bank" of the state was located in the capital, and was known locally as the "Dâr al-Sikka".[71][72]

In the 18th century the main categories of currencies produced locally and accepted in Algiers were:

- Algerian mahboub (Sultani), a gold coin weighing about 3.2g, with an inscription detailing the year it was produced and the year it will be decommisioned. Its production was discontinued under the reign of (1754-1766)

- Algerian budju, and the , two types of silver coinage, the most widely used types of currency in Algeria. A budju was worth 24 mazounas and 48 kharoubs and was further divided into "rube'-budju" (1/4 boudjous), "thaman-budju" (1/8 budju)

- minor conversion coins made of copper or billon, such as mazounas or kharoubs

- minor coins of small value such as the saïme or pataque-chique

Algiers also had some European (mainly Spanish) and Ottoman coins in circulation.[73]

Agriculture[]

The agricultural production of the country was mediocre, although fallowing and crop rotation were the most common way of production, techniques and tools were obsolete by the 18th and 19th century. Agricultural products were varied: wheat, corn, cotton, rice, tobacco, watermelon and vegetables were the most commonly grown things. In and around towns grapes and pomegranates were cultivated. In mountainous areas of the country, fruit trees, figs and olive trees were grown. The main agricultural export of the country was wheat.[74]

Milk was not often consumed and did not form a major part of the Algerian cuisine. The price of meat was low in Algeria before 1830, and many tribes brought in large amounts of income solely through the sale of cattle leather, although after the collapse of the Deylik and the arrival of the French the demand for cattle meat rapidly increased.[75] Wool and lamb meat were also produced in very high numbers.[75]

The majority of the western population south of the Tell Atlas and the people of the Sahara were pastoralists whose main produce was wool which was sometimes exported to be sold on the markets of the north, while the population in the north and east were settled in villages and did agriculture. The state and urban notables (mainly Arabs, Berbers, and Kouloughlis) owned lands near the main towns of the country which were cultivated by tenant farmers under the "khammas" system.[26]

Manufacturing and craftsmanship[]

Manufacturing was poorly developed and restricted to shipyards, but craftsmanship was rich and was present throughout the country.[74] Cities were the seat of great craft and commercial activity. The urban people were mostly artisans and merchants, notably in Nedroma, Tlemcen , Oran , Mostaganem, Kalaa, Dellys , Blida, Médéa, Collo, M'Sila, Mila and Constantine . The most common forms of craftmanship were weaving, woodturning, dyeing and production of ropes, and various tools.[76] In Algiers, a very large number of trades were practiced, and the city was home to many establishments: foundries, shipyards, various workshops, shops, and stalls. Tlemcen had more than 500 looms in it. Even in the small towns where the link with the rural world remained important, there were many craftsmen.[77]

Despite this, Algerian products were severely outcompeted by European products especially after the start of the industrial revolution in the 1760s.

In the 1820s modern industry was first introduced by Ahmed Bey ben Mohamed Chérif who built and opened large numbers of manufactories in the east of the country mainly focused around military production.[65]

Trade[]

Internal trade was extremely important, especially thanks to the Makhzen system, and large amounts of products needed in cities such as wool were imported from inner tribes of the country, and needed products were exported city to city.[78] Foreign trade was mainly conducted through the Mediterranean Sea and land exports to other neighbouring countries such as Tunisia and Morocco. When it came to land trade (both internal and external) transport was mainly done on the backs of animals, but carts were also used. The roads were suitable for vehicles, and many posts held by the Odjak and the Makhzen tribes provided security. In addition, caravanserais (known locally as fonduk) allowed travelers to rest.[78]

Although control over the sahara was often loose, Algiers's economic ties with the sahara were very important,[79] and Algiers and other Algerian cities were one of the main destinations of the Trans-Saharan slave trade.[80]

Political status[]

1518-1659[]

Inbetween 1518 and 1671, the rulers of the Regency were chosen by the Ottoman sultan. During the first few decades, Algiers was completely aligned with the Ottoman Empire, although it later gained a certain level of autonomy as it was the westernmost province of the Ottoman Empire, and administering it directly would have been problematic.

1659-1710[]

During this period a form of Dual leadership was in place, with the Aghas, after 1671 Deys, sharing power and influence with a Pasha appointed by the Ottoman sultan from Constantinople.[32] After 1671, the Deys became the main leaders of the country, although the Pashas still retained some power.[81]

1710-1830[]

After a coup by Baba Ali Chaouch the Political situation of Algiers became complicated.

Relation with the Ottoman Empire[]

Some sources describe it as completely independent from the Ottomans,[82][83][84] albeit the state was still nominally part of the Ottoman Empire.[85]

Despite the Ottomans having no influence in Algiers, and the Algerians completely ignoring orders from the Ottoman Sultan, such as in 1784.[17] In some cases Algiers also participated in the Ottoman Empire's wars, such as the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792),[86] albeit this was not common, and in 1798 for example Algiers sold wheat to the French Empire campaigning in Egypt against the Ottomans through two Jewish traders.

, dey of Algiers in one notorious example shouted at an Ottoman envoy for claiming that the Ottoman Padishah was the king of Algiers ("King of Algiers? King of Algiers? If he is the King of Algiers then who am i?"),[87] albeit it isn't known whether if this was something that happened only once thanks to the short temper of the Opium-smoker Cur Abdy, or if the Ottoman sultan was actually not recognized as legitimate in Algiers.

In some cases, Algiers was declared to be a country rebelling against the holy law of islam by the Ottoman Caliph.[88] This usually meant a declaration of war by the Ottomans against the Deylik of Algiers.[88] This could happen due to many reasons. For example under the rule of Haji Ali Dey, Algerian pirates regularly attacked Ottoman shipments, and Algiers waged war against the Beylik of Tunis,[89] despite several protests by the Ottoman Porte, which resulted in a declaration of war.

It can be thus said that the relationship between the Ottoman Empire and Algiers mainly depended on what the Dey at the time wanted. While in some cases, if the relationship between the two was favorable, Algiers did participate in Ottoman wars,[86] Algiers otherwise remained completely autonomous from the rest of the Empire similar to the other Barbary States.

Demography[]

The population of the Regency of Algiers in 1830 has been estimated at between 3 and 5 million,[90] of whom 10,000 were 'Turks' (including people from Kurdish, Greek and Albanian ancestry[91]) and 5,000 Kouloughli civilians (from the Turkish kul oğlu, "son of slaves (Janissaries)", i.e. creole of Turks and local women).[92] By 1830, more than 17,000 Jews were living in the Regency.[93]

See also[]

- List of Ottoman governors of Algiers

- Conflicts between the Regency of Algiers and the Cherifian Dynasties

- Kingdom of Tlemcen

Notes[]

- ^ In the historiography relating to the regency of Algiers, it has been named "Kingdom of Algiers",[4] "republic of Algiers",[5] "State of Algiers",[6] "State of El-Djazair",[7] "Ottoman Regency of Algiers",[6] "precolonial Algeria", "Ottoman Algeria",[8] etc. The Algerian historian said that "Algeria was first a regency, a kingdom-province of Ottoman Empire and then a State with a large autonomy, even independent, called sometimes kingdom or military republic by the historians, but still recognizing the spiritual authority of the caliph of Istanbul".[9]

- ^ The French historians Ahmed Koulakssis and write that "it's the same word, in international treaty which describes the city and the country it commands : Al Jazâ’ir".[10] Gilbert Meynier adds that "even if the path is difficult to build a State on the rubble of Zayanid's and Hafsids States [...] now, we speak about dawla al-Jaza’ir[11] (power-state of Algiers)"...

References[]

- ^ Gabor Agoston; Bruce Alan Masters (2009-01-01). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- ^ The red-and-yellow-striped banner flew over the city of Algiers in 1776 according to an article in The Flag Bulletin, Volume 25 (1986), p. 166. F. C. Leiner, The End of Barbary Terror: America's 1815 War Against the Pirates of North Africa (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 7, describes a green flag with white crescent and stars being raised on Algerian pirate vessels in 1812. According to Tarek Kahlaoui, Creating the Mediterranean: Maps and the Islamic Imagination (Brill, 2018), p. 216, the city of Algiers is represented by a flag of red, yellow and green horizontal stripes in an Ottoman atlas of 1551. According to an 1849 engraving by Gustav Feldweg, the former Algerian flag was an arm holding a sword on a red field and the flag of the Algerian corsairs was a skull and crossbones on the same field. See also Historical flags of Algeria.

- ^ Anthony Finley (1824). A New General Atlas, Comprising a Complete Set of Maps: Representing the Grand Divisions of the Globe, Together with the Several Empires, Kingdoms and States in the World. Anthony Finley. p. 57.

- ^ Tassy 1725, pp. 1, 3, 5, 7, 12, 15 et al

- ^ Tassy 1725, p. 300 chap. XX

- ^ a b Ghalem & Ramaoun 2000, p. 27

- ^ Kaddache 1998, p. 3

- ^ Panzac 1995, p. 62

- ^ Kaddache 1998, p. 233

- ^ Koulakssis & Meynier 1987, p. 17

- ^ Meynier 2010, p. 315

- ^ Mémoires de la Société Bourguignonne de Géographie et d'Histoire, Volumes 11-12 Societé Bourguignonne de Géographie et d'Histoire, Dijon

- ^ Nouvelle géographie universelle: La terre et les hommes, Volume 11 Reclus Librairie Hachette & Cie.,

- ^ Sands of Death: An Epic Tale Of Massacre And Survival In The Sahara Michael Asher Hachette UK,

- ^ Collective coordinated by Hassan Ramaoun, L'Algérie : histoire, société et culture, , 2000, 351 p. (ISBN 9961-64-189-2), p. 27

- ^ Hélène Blais. "La longue histoire de la délimitation des frontières de l'Algérie", in Abderrahmane Bouchène, Jean-Pierre Peyroulou, Ouanassa Siari Tengour and Sylvie Thénault, Histoire de l'Algérie à la période coloniale : 1830-1962, et Éditions Barzakh, 2012 (ISBN 9782707173263), p. 110-113.

- ^ a b "Relations Entre Alger et Constantinople Sous La Gouvernement du Dey Mohammed Ben Othmane Pacha, Selon Les Sources Espagnoles". docplayer.fr. Retrieved 2021-02-12.

- ^ An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire p.107ff

- ^ ↑ Kamel Filali, L'Algérie mystique : Des marabouts fondateurs aux khwân insurgés, XVe-XIXe siècles, Paris, Publisud, coll. « Espaces méditerranéens », 2002, 214 p. (ISBN 2866008952), p. 56

- ^ III, Comer Plummer (2015-09-09). Roads to Ruin: The War for Morocco In the Sixteenth Century. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4834-3104-8.

- ^ Gaïd, Mouloud (1978). Chronique des beys de Constantine (in French). Office des publications universitaires.

- ^ Sketches of Algeria During the Kabyle War By Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley: Pg 118

- ^ Memoirs Of Marshal Bugeaud From His Private Correspondence And Original Documents, 1784-1849 Maréchal Thomas Robert Bugeaud duc d’Isly

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islamedited by John L. Esposito: Pg 165

- ^ Naylorp, by Phillip Chiviges (2009). North Africa: a history from antiquity to the present. University of Texas Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-292-71922-4. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Abun-Nasr, Jamil M. (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780521337670.

[In 1671] Ottoman Algeria became a military republic, ruled in the name of the Ottoman sultan by officers chosen by and in the interest of the Ujaq.

- ^ a b c d e Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (30 January 2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Tenenti, Alberto Tenenti (1967). Piracy and the Decline of Venice, 1580-1615. University of California Press. p. 81. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "Moonlight View, with Lighthouse, Algiers, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Harris, Jonathan Gil (2003). Sick Economies: Drama, mercantilism, and disease in Shakespeare's England. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 152ff. ISBN 978-0-8122-3773-3. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Martin, Henri (1864). Martin's History of France. Walker, Wise & Co. p. 522. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ a b Algeria: Tableau de la situation des établissements français dans l'Algérie en 1837-54. Journal des opérations de l'artillerie pendant l'expedition de Constantine, Oct. 1837. Tableau de la situation des établissements français dans l'Algérie précédé de l'exposé des motifs et du projet de loi, portant demande de crédits extraordinaires au titre de l'exercice. 1842. pp. 412–.

- ^ "Dayı". Nişanyan Sözlük. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ Leaves from a Lady's Diary of Her Travels in Barbary. H. Colburn. 1850. pp. 139–.

- ^ Eugène Sue (1836). Histoire de la marine française XVIIe siècle Jean Bart (in French). Lyon Public Library. F. Bonnaire.

- ^ Robert Lambert Playfair; Sir Robert Lambert Playfair (1884). The Scourge of Christendom: Annals of British Relations with Algiers Prior to the French Conquest. Smith, Elder & Company. pp. 142–.

- ^ 29308232. "Histoire générale de la Tunisie, tome 3 : Les Temps Modernes". Issuu. Retrieved 2021-02-11.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne (in French). 1834.

- ^ Kaddache 2011, p. 432

- ^ Tayeb Chenntouf (1999). "" La dynamique de la frontière au Maghreb. ", Des frontières en Afrique du xiie au xxe siècle" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3 - J. D. Fage: Pg 408

- ^ Pages 82 and 104, Death in Babylon: Alexander the Great and Iberian Empire in the Muslim Orient

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3 - J. D. Fage: Pg 406

- ^ Politica e diritto nelle interrelazioni di Solimano il Magnifico

- ^ Mers el Kébir: la rade au destin tourmenté

- ^ Morocco in the Reign of Mawlay Sulayman - Mohamed El Mansour Middle East & North African Studies Press, 1990 - Morocco - 248 pages: Pg 104

- ^ Kidd, Charles, Williamson, David (editors). Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage (1990 edition). New York: St Martin's Press, 199

- ^ Boyer, P. (1970). "Des Pachas Triennaux à la révolution d'Ali Khodja Dey (1571-1817)". Revue Historique. 244 (1 (495)): 99–124. ISSN 0035-3264. JSTOR 40951507.

- ^ Boyer, Pierre (1973). "La révolution dite des "Aghas" dans la régence d'Alger (1659-1671)". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 13 (1): 159–170. doi:10.3406/remmm.1973.1200.

- ^ Mahfoud Kaddache, L'Algérie des Algériens, EDIF 2000, 2009, p. 413

- ^ "Notice sur le Bey d'Oran, Mohammed el Kebir. Revue africaine| Bulletin de la Société historique algérienne". revueafricaine.mmsh.univ-aix.fr. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Bastide, Tristan Arbousse (2008). Du couteau au sabre (in French). Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-4073-0253-9.

- ^ Stone, George Cameron (1999-01-01). Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-40726-5.

- ^ Macdonald, Paul K. (2014). Networks of Domination: The Social Foundations of Peripheral Conquest in International Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936216-5.

- ^ Jean Andre Peyssonnel, Voyages dans les regences de Tunis and d'Alger, published by Dureau de la Malle: Volume 1, p. 404

- ^ Brenner, William J. (2016-01-29). Confounding Powers: Anarchy and International Society from the Assassins to Al Qaeda. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10945-2.

- ^ Extract from Tachrifat , reported by Pierre Boyer, 1970, page 84

- ^ Shuval, Tal (2013-09-30), "Chapitre II. La caste dominante", La ville d’Alger vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle : Population et cadre urbain, Connaissance du Monde Arabe, Paris: CNRS Éditions, pp. 57–117, ISBN 978-2-271-07836-0, retrieved 2021-03-13

- ^ Abou-Khamseen, Mansour Ahmad (1983). The First French-Algerian War (1830-1848): A Reappraisal of the French Colonial Venture and the Algerian Resistance. University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ a b c d e Panzac, Daniel (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12594-0.

- ^ Algerian arab manuscript, Al Zahra al Nâira, cited in Kaddache 2011, p. 445

- ^ Paradis, Jean-Michel Venture de (2006). Alger au XVIII siècle, 1788-1790: mémoires, notes et observations d ̓un dipolomate-espion (in French). Éditions grand-Alger livres. ISBN 978-9961-819-65-4.

- ^ Surkis, Judith (2019-12-15). Sex, Law, and Sovereignty in French Algeria, 1830–1930. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-3951-4.

- ^ Guyon, Jean-Louis-Geneviève (1852). Voyage d'Alger aux Ziban l'ancienne Zebe en 1847 (etc.) (in French). Impr. du Gouvernement.

- ^ a b Nabli, Mustapha K.; Nugent, Jeffrey B. (1989). The New Institutional Economics and Development: Theory and Applications to Tunisia. North-Holland. ISBN 978-0-444-87487-0.

- ^ Gregory Hanlon. "The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800." Routledge: 1997. Pages 27-28.

- ^ Algerian arab manuscript, Al Zahra al Nâira, cited in Kaddache 2011, p. 445

- ^ "محاضرة : الحرب التونسية الجزائرية و تخلص حمودة باشا من التبعية سنة 1807". 2017-08-03. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Boyer, P. (1985-11-01). "Agha". Encyclopédie berbère (in French) (2): 254–258. doi:10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.915. ISSN 1015-7344.

- ^ Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S.; Friedberg, Robert (2017-01-05). Gold Coins of the World - 9th edition: From Ancient Times to the Present. An Illustrated Standard Catlaog with Valuations. Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-009-7.

- ^ Courtinat, Roland (2007). Chroniques pour servir et remettre à l'endroit l'histoire du Maghreb (in French). Dualpha. ISBN 978-2-35374-029-1.

- ^ Safar Zitoun, Madani (2009-09-30). "Tal Shuval, La ville d'Alger vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Population et cadre urbain". Insaniyat / إنسانيات. Revue algérienne d'anthropologie et de sciences sociales (in French) (44–45): 252–254. ISSN 1111-2050.

- ^ Ould Cadi Montebourg, Leïla (2014-10-21). Alger, une cité turque au temps de l'esclavage : À travers le Journal d'Alger du père Ximénez, 1718-1720. Voix des Suds (in French). Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée. ISBN 978-2-36781-083-6.

- ^ a b Belvaude, Catherine (1991). L'Algérie. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 2-86537-288-X. OCLC 24893890.

- ^ a b Morell, John Reynell (1854). Algeria: The Topography and History, Political, Social, and Natural, of French Africa. N. Cooke.

- ^ Kaddache 1998, p. 203

- ^ Kaddache 1998, p. 204

- ^ a b Kaddache 1998, p. 218

- ^ Kouzmine, Yaël; Fontaine, Jacques; Yousfi, Badr-Eddine; Otmane, Tayeb (2009). "Étapes de la structuration d'un désert : l'espace saharien algérien entre convoitises économiques, projets politiques et aménagement du territoire". Annales de géographie. 670 (6): 659. doi:10.3917/ag.670.0659. ISSN 0003-4010.

- ^ Wright, John (2007-04-03). The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17986-2.

- ^ Lane-Poole, Stanley; Kelley, James Douglas Jerrold (1890). The Story of the Barbary Corsairs. G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8482-4873-4.

- ^ Association, American Historical (1918). General Index to Papers and Annual Reports of the American Historical Association, 1884-1914. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Association, American Historical (1918). Annual Report of the American Historical Association. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Hutt, Graham (2019-01-01). North Africa. Imray, Laurie, Norie and Wilson Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84623-883-3.

- ^ Colburn's United Service Magazine and Naval and Military Journal. Henry Colburn. 1857.

- ^ a b Anderson, R. C. (1952). Naval wars in the Levant, 1559-1853. Princeton. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005292860.

- ^ "Les Deys 3". exode1962.fr. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ a b Carbondale; Oxford, Near Eastern History Group; Center, University of Pennsylvania Middle East (1977). Studies in Eighteenth Century Islamic History. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-0819-4.

- ^ Panzac, Daniel (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12594-0.

- ^ Kamel Kateb (2001). Européens, "indigènes" et juifs en Algérie (1830-1962): représentations et réalités des populations. INED. pp. 11–16. ISBN 978-2-7332-0145-9.

- ^ Isichei, Elizabeth Isichei (1997). A history of African societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 263. ISBN 0-521-45444-1. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Isichei, Elizabeth Isichei (1997). A history of African societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-521-45444-1. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Yardeni, Myriam (1983). Les juifs dans l'histoire de France: premier colloque internationale de Haïfa. BRILL. p. 167. ISBN 9789004060272. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

Bibliography[]

- Konstam, Angus (2016). The Barbary Pirates. 15th–17th Centuries. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1543-9.

- Pierre Boyer, « Le problème Kouloughli dans la régence d'Alger», Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, vol. 8, no 1, 1970, p. 79-94 (ISSN 0035-1474, DOI 10.3406/remmm.1970.1033)

- Ottoman Algeria

- Former countries in Africa

- States and territories established in 1515

- States and territories disestablished in 1830

- 1830 disestablishments in the Ottoman Empire

- Eyalets of the Ottoman Empire in Africa

- 1515 establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 1830s disestablishments in Africa

- 16th century in Algiers

- Barbary Coast