Ovarian germ cell tumors

| Ovarian germ cell tumors | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Bloating, abdominal distention, ascites, dyspareunia |

Ovarian germ cell tumors (OGCTs) are heterogeneous tumors that are derived from the primitive germ cells of the embryonic gonad, which accounts for about 2.6% of all ovarian malignancies.[1] There are four main types of OGCTs, namely dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and choriocarcinoma.[1]

Dygerminomas are Malignant germ cell tumor of ovary and particularly prominent in patients diagnosed with gonadal dysgenesis.[1] OGCTs are relatively difficult to detect and diagnose at an early stage because of the nonspecific histological characteristics.[1] Common symptoms of OGCT are bloating, abdominal distention, ascites, and dyspareunia.[1] OGCT is caused mainly due to the formation of malignant cancer cells in the primordial germ cells of the ovary.[1] The exact pathogenesis of OGCTs is still unknown however, various genetic mutations and environmental factors have been identified.[1] OGCTs are commonly found during pregnancy when an adnexal mass is found during a pelvic examination, ultrasound scans show a solid mass in ovary or blood serum test shows elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels.[1] They are unlikely to have metastasized and therefore the standard tumor management is surgical resection, coupled with chemotherapy.[2] The occurrence rate is less than 3% worldwide.[3]

Classification[]

OGCTs can be classified into dysgerminoma, teratomas, yolk sac tumors, and choriocarcinomas, listed in the order of prevalence.[1]

Dysgerminoma[]

Dysgerminomas are comparable to testicular seminomas and account for approximately 32- 37% of all OGCTs.[1] They are particularly prominent in individuals with dysgenic gonads of 46, XY pure gonadal dysgenesis patients.[1] Based on gross examinations, dysgerminomas are characterized by having a ‘solid, lobulated, tan, flesh-like gross appearance with a smooth surface'.[1] Microscopically, the cellular structure is distinguished by a round-ovoid shape containing ample eosinophilic cytoplasm and an irregularly shaped nuclei.[1] The uniformly positioned cells are separated through the fibrous strands and lymphocytic infiltration is commonly observed.[5]

Teratomas[]

Teratoma are most common germ cell tumor of ovary. Teratomas can be divided into two types: mature teratoma (benign) and immature teratoma (malignant). Immature teratomas contain immature or embryonic tissue which significantly differentiates them from mature teratomas as they carry dermoid cysts.[7] It is commonly observed in 15 to 19-year-old women and rarely in women after menopause.[8] Immature teratomas are characterized with a diameter of 14–25 cm, encapsulated mass, cystic areas, and occasional appearance of hemorrhagic areas.[9] The stage of immature teratomas is determined depending on the amount of immature neuroepithelium tissue detected.[7]

Yolk sac tumor[]

The ovarian yolk sac tumors, also known as endodermal sinus tumors, are accountable for approximately 15.5% of all OGCTs.[11] They have been observed in women particularly in their early ages, and rarely after 40 years of age.[12] The critical pathologic features are a smooth external surface and capsular tears due to their rapid rate of growth. A study consisting of 71 individual cases of ovarian yolk sac tumor provides evidence to the proliferation of the tumor. In one of the cases, the pelvic examination revealed normal activity until a 9 cm and 12 cm sized tumor was discovered 4 weeks later.[12] In another case, a 23 cm tumor was discovered in a pregnant woman who was monitored regularly and had normal findings until oophorectomy became essential.[12] Histologically, these tumors are characterized by mixed solid and cystic components.[1] The mixed solid components are characterized by a soft gray to yellow solid components accompanied with significant hemorrhage and necrosis. The cysts are approximately 2 cm in diameter and populated throughout the tissue which results in giving the neoplasm a ‘honeycombed appearance’.[1]

Choriocarcinoma[]

Choriocarcinomas are exceptionally rare which account for 2.1%-3.4% of all OGCTs.[14] Under gross examination, the syncytiotrophoblast cells are aligned in a plexiform arrangement with the mononucleated cytotrophoblast cells surrounding the foci of the hemorrhage.[1] Choriocarcinomas can be divided into gestational choriocarcinomas and non-gestational choriocarcinomas which have immunohistochemical differences.[15]

Signs and Symptoms[]

OGCTs are relatively difficult to detect and diagnose at an early stage mainly because the symptoms are normally subtle and nonspecific. They become detectable when as they become large, tangible masses. Symptoms include bloating, abdominal distention, ascites, and dyspareunia.[16] In rare cases where the tumor ruptures, acute abdominal pain can be experienced.[17] The critical indicator of malignancy is usually the appearance of the Sister Mary Joseph Nodule.[18] OGCTs can further give rise to ovarian torsion, hemorrhage, and even isosexual precocious puberty in young children.[19]

Causes[]

The exact cause of OGCT is yet to be determined. However, a few factors have been identified which may contribute to increased risk of OGCTs including endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and genetic risk factors.[20] Individuals who are more prone to developing OGCTs usually contain the autosomal dominant, BRCA-1/ BRCA-2, mutations.[20] Complications with other cancers such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, also known as the Lynch syndrome, increases the risk of developing ovarian cancer.[20] Pregnancy, breastfeeding, and oral contraceptives are known to have reduced risk for OGCTs.[20] The etiology of OGCT is still under study, however, genetic alterations may contribute to development of OGCTs, such as the classical tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes. Along with genetic modifications, certain environmental factors such as endocrine disruptors, presence of a daily routine that affects the individual's biochemistry, and exposure to maternal hormones could also contribute to the proliferation of OGCT.[20] A recent study on rats showed the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance supporting the influence of hazardous environmental substances, including plastics, pesticides, and dioxins, on the pathogenesis of OGCT.[20]

Pathogenesis[]

Nonetheless, a few speculations for the causes have been made. During ovulation, the follicle ruptures resulting in epithelial cell damage.[1] In order to heal the tissue and replace the damage, the cells undergoes cell division. Each time the cell divides, there is a possibility for mutations to occur and the chance of tumor formation increases.[1] The tumor is caused when the germ cells in the ovaries begin divide uncontrollably and become malignant which are characterized with their less organized nuclei and unclearly defined border.[1] Another potential etiology is the dysfunctioning of the tumor suppressor gene, TRC8/RNF139, or even karyotypic abnormalities after close molecular examination.[21]

OGCT has its roots in embryonic development where the primordial germ cells (PGCs) are isolated in early stages and have the ability to alter the genome as well as the transcriptome.[20] OGCTs can be attributed to the internal mechanism of PGCs and their transforming characteristics.[20]

Staging[]

After OGCT has been diagnosed, various tests will be conducted to determine whether the cancer has spread to other areas in the body. The spread of OGCT is identified through different stages: stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV namely.

Stage I: Tumor cells are localized in the ovaries or the fallopian tubes without extensive spread to other body regions.[22]

Stage II: The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and has spread into the pelvis.[22]

Stage III: The cancer has spread beyond the pelvis into the abdomen and to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (located at the back of the abdomen). The substages are characterized by the relative size of the tumor.[22]

Note: Stage II ovarian cancer will also be declared if the cancerous cells have spread to the liver. Stage IV: The cancer has spread outside of the abdomen and pelvis to more distant organs, such as the lungs.[22]

Diagnosis[]

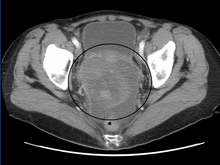

The preliminary diagnosis begins with a pelvic examination, serum tumor marker test and imaging. Physicians may feel a large palpable mass or lump in lower abdomen upon insertion of the gloved fingers into the vagina. To further identify the histologic subtypes of OGMTs, blood samples of patients are collected to analyse the serum level of biomarkers released by the tumor cells. A surge in the plasma levels of human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein is indicative of OGMTs.[1] Lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase and cancer antigen 125 might potentially increase as well.[24] To visualize the location and morphology of the tumor, transvaginal ultrasonography is usually employed.[1] The most characteristic appearance is a parenchymal-like heteroechoic mass with sharp borders and high vascularization.[1] Computed tomography would produce stacked image inside the peritoneal region of the body to visualise the lobular pattern of the tumour.[1] Usually for dysgerminoma, solid mass being compartmentalized into lobules with enhancing septa may be evident for haemorrhage or necrosis.[1]

Preoperative procedures[]

In accordance with FIGO staging guidelines, comprehensive surgical staging will be conducted to examine the extent of tumor spread via peritoneal regions or lymph drainages.

28% of stage II patients will be found with the development of secondary malignant growths at lymph nodes with a distance from a primary site of cancer, called lymph node metastasis.[1]

There are three major lymphatic drainage pathways:[1]

- drainage to the paraaortic lymph nodes via ovarian veins

- drainage from broad ligament to the iliac lymph nodes

- drainage from round ligament to the inguinal lymph nodes

Palpation or biopsies of unilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes will be conducted as a preoperative step to deduce the prognosis of the tumour and lymphatic spread[1]

Peritoneal biopsies and omentectomy will also be employed to evaluate the extent of tumour content spillage or implantation in peritoneal cavity.[1] Tumor cells may shed off from the original site into the peritoneal cavity and implant onto the liver capsule surface or diaphragm.[24] They may clog up inside the lymphatic vessel around the diaphragm and prevent resorption of peritoneal fluid.[24] In the end, pericardiophrenic lymphadenopathy and ascites may result from this frank invasion.[1][24]

Treatment[]

Surgery[]

Malignant OGCTs are predominantly unilateral and chemosensitive, which means they are localized in only one side of the ovary.[24] Fertility-preserving surgery is primarily standardized to keep the contralateral ovary and fallopian tube intact, also known as unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[1][24] For Stage II patients with observable metastasis, cytoreductive surgery may be performed to debulk the volume of the tumor, such as hysterectomy (removal of all or part of the uterus) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[1][24] A surgical incision at the abdominal cavity after the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, called second look laparotomy, is best applicable for patients reported with teratomatous elements after previous cytoreductive surgery.[1][24]

Adjuvant Chemotherapy[]

With a recurrence up to 15-25% for early-stage patients,[1] adjuvant chemotherapy needs to couple with surgical resection of tumor to ensure full salvage. For systemic chemotherapy (issued orally or intravenously), the regimen is standardised in every FIGO staging to comprise bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, also known as the .[2] Patients should be issued with 3-4 cycles of BEP to ensure full salvage.[2] Depending on the personalised conditions, some patients who are non-responders to BEP therapy will be prescribed with salvage therapy, which consists of cisplatin, ifosfamide and paclitaxel.[2][26] Yet, it is likely that OGCT survivors after BEP therapy will have premature menopause at a rough age of 36.[24] Alternatively, some hospitals opted for platinum-based chemotherapy since the platinum complexes present in the drug intervenes DNA transcription by forming chemical cross-links within the DNA strands, which prevents the reproduction of cancerous cells.[27] The major elements are cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin.[28] It has been reported with full recovery among early-stage patients and only a quarter of advanced-stage patients are not salvaged potentially due to drug resistance.[1][29]

For advanced-stage patients, after cytoreductive surgery, invisible microscopic cancerous cells or nodules may still be present at the site of infection.[27] Therefore, doctors may instill a heated chemotherapy solution (~42-43 °C) into the abdominal cavity through carters tubes for 1.5 hours.[30] Based on the principle that cancer cells normally dies at 40 °C, somatic cells remains unaffected since they die at 44 °C.[30] This novel method is proven effective with only 10% recurrence rate and no mortality recorded.[31] It is known as the hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), containing docetaxel, and cisplatin.[31] Given the drug is disseminated locally in intraperitoneal regions, it has no systemic side effects on other actively reproducing cells and is preferred over systemic chemotherapy.[30]

Typically, uncontrollable drug distribution in systemic chemotherapy results in myelosuppression, specifically with observed febrile neutropenia, neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, and nephrotoxicity.[2] Remedial treatments to deal with chemotherapy-induced toxicities is through injection of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or myeloid growth factors or oral intake of prophylactic antibiotics.[2]

Epidemiology[]

OGCT is a rare tumour under the scope of ovarian cancer, accounting for less than 5% of all ovarian malignancies. It occurs mostly in 15-19-year-old women and shows 75% incidence rate for women aged <30 years.[31] In 2011, the number of new cases occurred worldwide is 5.3 per million.[32] In most countries, the occurrence rate on average is less than 3% of the population.[3] However, Asia has reported the highest proportion of cases up to 4.3% due to the younger age profile of the population.[3] For other regions, the incidence rates reported are 2.5% in Oceania, 2.0% in North America and 1.3% in Europe.[3]

The five-year survival rates have reached up to 90-92%, which is much higher than that of epithelial ovarian cancers.[33] The main reason is the high effectiveness of platinum-based chemotherapy.[1]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Elsayes KM, Baskin H, Mourad A, Foster BR, Jarboe EA, Menias CO (2014). "Ovarian malignant germ cell tumors: cellular classification and clinical and imaging features". Radiographics. 34 (3): 777–801. doi:10.1148/rg.343130067. PMID 24819795.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors" (PDF). April 2013. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ a b c d Matz M, Coleman MP, Sant M, Chirlaque MD, Visser O, Gore M, Allemani C (February 2017). "The histology of ovarian cancer: worldwide distribution and implications for international survival comparisons (CONCORD-2)". Gynecologic Oncology. 144 (2): 405–413. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.019. PMC 6195192. PMID 27931752.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-02-13, retrieved 2019-04-09

- ^ Hazard FK (2019). "Ovarian Dysgerminomas Pathology: Overview of Ovarian Dysgerminomas, Differentiating Ovarian Dysgerminomas, Laboratory Markers". Medscape.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-03-14, retrieved 2019-04-10

- ^ a b Medeiros F, Strickland KC (January 2018). "Chapter 26: Germ cell tumors of the ovary.". Diagnostic Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology (third ed.). pp. 949–1010. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-44732-4.00026-1. ISBN 978-0-323-44732-4.

- ^ Templeman CL, Hertweck SP, Scheetz JP, Perlman SE, Fallat ME (December 2000). "The management of mature cystic teratomas in children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis". Human Reproduction. 15 (12): 2669–72. doi:10.1093/humrep/15.12.2669. PMID 11098043.

- ^ Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL (2001). "Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics". Radiographics. 21 (2): 475–90. doi:10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr09475. PMID 11259710.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-02-01, retrieved 2019-04-10

- ^ Talerman A (July 1975). "The incidence of yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tumor) elements in germ cell tumors of the testis in adults". Cancer. 36 (1): 211–5. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197507)36:1<211::AID-CNCR2820360122>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 1203848.

- ^ a b c Kurman RJ, Norris HJ (December 1976). "Endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary: a clinical and pathologic analysis of 71 cases". Cancer. 38 (6): 2404–19. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197612)38:6<2404::aid-cncr2820380629>3.0.co;2-3. PMID 63318.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-02-23, retrieved 2019-04-10

- ^ Smith HO, Berwick M, Verschraegen CF, Wiggins C, Lansing L, Muller CY, Qualls CR (May 2006). "Incidence and survival rates for female malignant germ cell tumors". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107 (5): 1075–85. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000216004.22588.ce. PMID 16648414. S2CID 25914370.

- ^ Ulbright TM (February 2005). "Germ cell tumors of the gonads: a selective review emphasizing problems in differential diagnosis, newly appreciated, and controversial issues". Modern Pathology. 18 Suppl 2 (2): S61-79. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800310. PMID 15761467.

- ^ "Germ cell ovarian tumours | Ovarian cancer | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- ^ Moniaga NC, Randall LM (February 2011). "Malignant mixed ovarian germ cell tumor with embryonal component". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 24 (1): e1-3. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2010.05.001. PMC 5111966. PMID 20869284.

- ^ Calongos G, Ogino M, Kinuta T, Hori M, Mori T (2016). "Sister Mary Joseph Nodule as a First Manifestation of a Metastatic Ovarian Cancer". Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016: 1087513. doi:10.1155/2016/1087513. PMC 5007344. PMID 27635270.

- ^ Williams SD (June 1998). "Ovarian germ cell tumors: an update". Seminars in Oncology. 25 (3): 407–13. PMID 9633853.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kraggerud SM, Hoei-Hansen CE, Alagaratnam S, Skotheim RI, Abeler VM, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Lothe RA (June 2013). "Molecular characteristics of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors and comparison with testicular counterparts: implications for pathogenesis". Endocrine Reviews. 34 (3): 339–76. doi:10.1210/er.2012-1045. PMC 3787935. PMID 23575763.

- ^ "Ovarian Dysgerminomas: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2019-03-18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d "Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Symptoms, Tests, Prognosis, and Stages". National Cancer Institute. 1980-01-01. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-03-19, retrieved 2019-04-10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bixel KL, Fowler J (2018). "Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors". Gynecologic Care. Cambridge University Press. pp. 350–359. doi:10.1017/9781108178594.037. ISBN 9781108178594.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-03-19, retrieved 2019-04-10

- ^ "Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors - Review of Cancer Medicines on WHO list of Essential Medicines" (PDF). Union for International Cancer Control. 2014.

- ^ a b "Chemotherapy". Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ "Platinum therapy (anti-cancer treatment) information". myVMC. 2005. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Wang Y, Yang JX, Yu M, Cao DY, Shen K (2018). "Malignant mixed ovarian germ cell tumor composed of immature teratoma, yolk sac tumor and embryonal carcinoma harboring an EGFR mutation: a case report". OncoTargets and Therapy. 11: 6853–6862. doi:10.2147/ott.s176854. PMC 6190639. PMID 30349318.

- ^ a b c "Peritoneal Cancer Treatment Boston". Tufts Medical Center. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ a b c Yu HH, Yonemura Y, Hsieh MC, Lu CY, Wu SY, Shan YS (2019). "Experience of applying cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for ovarian teratoma with malignant transformation and peritoneal dissemination". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 15: 129–136. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s190641. PMC 6338109. PMID 30679911.

- ^ Kaatsch P, Häfner C, Calaminus G, Blettner M, Tulla M (January 2015). "Pediatric germ cell tumors from 1987 to 2011: incidence rates, time trends, and survival". Pediatrics. 135 (1): e136-43. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1989. PMID 25489016. S2CID 1149576.

- ^ Wang Y, Yang JX, Yu M, Cao DY, Shen K (2018). "Malignant mixed ovarian germ cell tumor composed of immature teratoma, yolk sac tumor and embryonal carcinoma harboring an EGFR mutation: a case report". OncoTargets and Therapy. 11: 6853–6862. doi:10.2147/OTT.S176854. PMC 6190639. PMID 30349318.

External links[]

- Ovarian cancer