Oncology

This article is in list format but may read better as prose. (May 2017) |

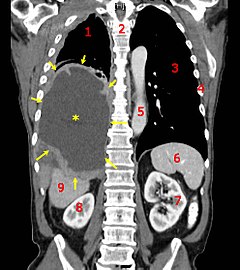

A coronal CT scan showing a malignant mesothelioma, indicated by the asterisk and the arrows | |

| Focus | Cancerous tumor |

|---|---|

| Subdivisions | Medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical oncology |

| Significant tests | Tumor markers, TNM staging, CT scans, MRI |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names |

|

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Oncology is a branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. A medical professional who practices oncology is an oncologist.[1] The name's etymological origin is the Greek word ὄγκος (óngkos), meaning 1. "burden, volume, mass" and 2. "barb", and the Greek word λόγος (logos), meaning "study".[2] The neoclassical term oncology was used from 1618, initially in neo-Greek, in cognizance of Galen's work on abnormal tumors, De tumoribus præter naturam (Περὶ τῶν παρὰ φύσιν ὄγκων).[3]

Cancer survival has improved due to three main components: improved prevention efforts to reduce exposure to risk factors (e.g., tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption),[4] improved screening of several cancers (allowing for earlier diagnosis),[5] and improvements in treatment.[6][7]

Cancers are often managed through discussion on multi-disciplinary cancer conferences[8] where medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, and organ-specific oncologists meet to find the best possible management for an individual patient considering the physical, social, psychological, emotional, and financial status of the patient.[9] It is very important for oncologists to keep up-to-date with the latest advancements in oncology, as changes in the management of cancer are quite common.

Because a cancer diagnosis can cause distress and anxiety,[10] clinicians may use a number of strategies such as SPIKES[11] for delivering the bad news.[12]

Risk factors[]

- Tobacco

- Tobacco exposure is the leading cause of cancer and death from it.[13] Smoking tobacco is strongly associated with increased risk of cancers of the lung, larynx, mouth, esophagus, throat, brain, bladder, kidney, liver, stomach, pancreas, colon, rectum, cervix, and acute myeloid leukemia. Smokeless tobacco (snuff or chewing tobacco) is associated with increased risks of cancers of the mouth, esophagus, and pancreas.[14]

- Alcohol

- Alcohol consumption increases risk of cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, larynx, liver, and breast. The risk of cancer is much higher for those who drink alcohol and also use tobacco.[15]

- Obesity

- Obese individuals have an increased risk of cancer of the breast, colon, rectum, endometrium, esophagus, kidney, pancreas, and gallbladder.[16]

- Age

- Advanced age is a risk factor for many cancers. The median age of cancer diagnosis is 66 years.[17]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2021) |

- Cancer-Causing Substances

- Cancer is caused by changes to certain genes that alter the way our cells function. Some of them are the result of environmental exposures that damage DNA. These exposures may include substances, such as the chemicals in tobacco smoke, or radiation, such as ultraviolet rays from the sun and other carcinogens.

- Infectious Agents

- Certain infectious agents, including oncoviruses, bacteria, and parasites, can cause cancer.

- Immunosuppression

- The body's immune response plays a role in defending the body against cancer, a concept known mainly because certain cancers occur at a greatly increased prevalence among people with immunosuppression.

Screening[]

Cancer screening is recommended for cancers of breast,[18] cervix,[19] colon,[20] and lung.[21]

Signs and symptoms[]

Signs and symptoms usually depend on the size and type of cancer.

- Breast cancer

- Lump in breast and axilla associated with or without ulceration or bloody nipple discharge.[22]

- Endometrial cancer

- Bleeding per vaginam.[23]

- Cervix cancer

- Bleeding after sexual intercourse.[24]

- Ovarian cancer

- Nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal distension, dyspepsia.[25]

- Lung cancer

- Persistent cough, breathlessness, blood in the sputum, hoarseness of voice.[26]

- Head and neck cancer

- Non-healing ulcer or growth, lump in the neck.[27]

- Brain cancer

- Persistent headache, vomiting, loss of consciousness, double vision.[28]

- Thyroid cancer

- Lump in the neck.[29]

- Oesophageal cancer

- Painful swallowing predominantly with solid food, weight loss.[30]

- Stomach cancer

- Vomiting, dyspepsia, weight loss.[31]

- Colon & rectal cancer

- Bleeding per rectum, alteration of bowel habits.[32]

- Liver cancer

- Jaundice, pain and mass in right upper abdomen.[33]

- Pancreatic cancer

- Weight loss, jaundice.[34]

- Skin cancer

- Non-healing ulcer or growth, mole with sudden increase in size or irregular border, induration, or pain.[35]

- Kidney cancer

- Blood in urine, abdominal lump.[36]

- Bladder cancer

- Blood in urine.[37]

- Prostate cancer

- Urgency, hesitancy and frequency while passing urine, bony pain.[38]

- Testis cancer

- Swelling of testis, back pain, dyspnoea.[39]

- Bone cancer

- Pain and swelling of bones.[40]

- Lymphoma

- Fever, weight loss more than 10% body weight in preceding 6 months and drenching night sweats which constitutes the B symptoms, lump in neck, axilla or groin.[41]

- Blood cancer

- Bleeding manifestations including bleeding gums, bleeding from nose, blood in vomitus, blood in sputum, blood stained urine, black coloured stools, fever, lump in neck, axilla, or groin, lump in upper abdomen.[26]

Diagnosis and staging[]

Diagnostic and staging investigations depend on the size and type of malignancy.

Blood cancer[]

Blood investigations including hemoglobin, total leukocyte count, platelet count, peripheral smear, red cell indices.

Bone marrow studies including aspiration, flow cytometry,[42] cytogenetics,[43] fluorescent in situ hybridisation and molecular studies.[44]

Lymphoma[]

Excision biopsy of lymph node for histopathological examination,[45] immunohistochemistry,[46] and molecular studies.[47]

Blood investigations include lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum uric acid, and kidney function tests.[48]

Imaging tests such as computerised tomography (CT scan), positron emission tomography (PET CT).[49]

Bone marrow biopsy.[50]

Solid tumors[]

Biopsy for histopathology and immunohistochemistry.[51]

Imaging tests like X-ray, ultrasonography, computerised tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET CT.[52]

Endoscopy including Nasopharyngoscopy, Direct & Indirect Laryngoscopy, Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Colonoscopy, Cystoscopy.

Tumor markers including alphafetoprotein (AFP),[53] Beta Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (β-HCG),[53] Carcinoembionic Antigen (CEA),[54] CA 125,[55] Prostate specific antigen (PSA).[56]

Treatment[]

Treatment depends on the size and type of cancer.

Solid tumors[]

- Breast cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapy (Her 2 neu inhibitors).[57]

- Cervix cancer

- Treatment options include radiation, surgery and chemotherapy.[58]

- Endometrial cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.[59]

- Ovary cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (VEGF inhibitors).[60]

- Lung cancer

- Treatment options include surgery and robot-assisted surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (EGFR & ALK inhibitors).[61]

- Head & Neck Cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiosurgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (EGFR inhibitors).[62]

- Brain cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiosurgery with the Cyberknife System, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (VEGF inhibitors).[57]

- Thyroid cancer

- Treatment options include surgery and radioactive iodine.[63]

- Oesophageal cancer

- Treatment options include radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery.[64]

- Stomach cancer

- Treatment options include chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, and targeted therapy (Her 2 neu inhibitors).[65][66]

- Colon cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (EGFR & VEGF inhibitors).[67]

- Rectum cancer

- Treatment options include chemotherapy, radiation, surgery.[68]

- Liver cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, Trans-arterial chemotherapy (TACE), Radio-frequency ablation (RFA), and multi-kinase (Sorafenib).[69]

- Pancreas cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.[70]

- Skin cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, targeted therapy (BRAF & MEK inhibitors), Immunotherapy (CTLA 4 & PD 1 inhibitors, and chemotherapy.[71]

- Kidney cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, multi-kinase inhibitors, and targeted therapy (mTOR & VEGF inhibitors).[72]

- Bladder cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.[73]

- Prostate cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, anti-androgens, and immunotherapy.[74]

- Testis cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.[75]

- Bone cancer

- Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.[76]

Lymphoma[]

It includes Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL):

- Hodgkin lymphoma (HL)

- Chemotherapy with ABVD or BEACOPP regimen and Involved field radiation therapy (IFRT).[77]

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)

- Chemo-immunotherapy (R-CHOP) for B cell lymphomas, and chemotherapy (CHOP) for T cell lymphomas.[78]

Blood cancer[]

Includes acute and chronic leukemias. Acute leukemias includes acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Chronic leukemias include chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

- Intensive chemotherapy phase for initial 6 months and maintenance chemotherapy for 2 years. Prophylactic cranial and stem cell transplantation for high-risk patients.[79]

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

- Induction with chemotherapy (Daunorubicin + Cytarabine), followed by consolidation chemotherapy (High dose cytarabine). Stem cell transplantation for high-risk patients.[80]

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): Chemo-immunotherapy (FCR or BR regimen) for symptomatic patients.[81]

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

- Targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Imatinib) as first-line treatment.[82]

Specialties[]

- The four main divisions:

- Medical oncology: focuses on treatment of cancer with chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and hormonal therapy.[83]

- Surgical oncology: focuses on treatment of cancer with surgery.[84]

- Radiation oncology: focuses on treatment of cancer with radiation.[84]

- Clinical oncology: focuses on treatment of cancer with both systemic therapies and radiation.[85]

- Sub-specialties in Oncology:

- Neuro-oncology: focuses on cancers of brain.

- Ocular oncology: focuses on cancers of eye.[86]

- Head & Neck oncology: focuses on cancers of oral cavity, nasal cavity, oropharynx, hypopharyx and larynx.[87]

- Thoracic oncology: focuses on cancers of lung, mediastinum, oesophagus and pleura.[88]

- Breast oncology: focuses on cancers of breast

- Gastrointestinal oncology: focuses on cancers of stomach, colon, rectum, anal canal, liver, gallbladder, pancreas.[89]

- Bone & Musculoskeletal oncology: focuses on cancers of bones and soft tissue.[90]

- Dermatological oncology: focuses on the medical and surgical treatment of skin, hair, sweat gland, and nail cancers

- Genitourinary oncology: focuses on cancers of genital and urinary system.[91]

- Gynecologic oncology: focuses on cancers of the female reproductive system.[92]

- Pediatric oncology: concerned with the treatment of cancer in children.[93]

- Adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology.[94]

- Hemato oncology: focuses on cancers of blood and stem cell transplantation

- Preventive oncology: focuses on epidemiology & prevention of cancer.[95]

- Geriatric oncology: focuses on cancers in elderly population.[96]

- Pain & Palliative oncology: focuses on treatment of end stage cancer to help alleviate pain and suffering.[97]

- Molecular oncology: focuses on molecular diagnostic methods in oncology.[98]

- Nuclear medicine oncology: focuses on diagnosis and treatment of cancer with radiopharmaceuticals.

- Psycho-oncology: focuses on psychosocial issues on diagnosis and treatment of cancer patients.

- Veterinary oncology: focuses on treatment of cancer in animals.[99]

- Emerging specialties:

- Cardiooncology is a branch of cardiology that addresses the cardiovascular impact of cancer and its treaments[100]

- Computational oncology. An example is PRIMAGE. This four-year EU-funded Horizon 2020 project was launched in December 2018. The project proposes a cloud-based platform to support decision making in the clinical management of malignant solid tumours, offering predictive tools to assist diagnosis, prognosis, therapies choice and treatment follow up, based on the use of novel imaging biomarkers, in-silico tumour growth simulation, advanced visualisation of predictions with weighted confidence scores and machine-learning based translation of this knowledge into predictors for the most relevant, disease-specific, Clinical End Points.[101][102]

Research and progress[]

- Leukemia,[103] Lymphoma,[104] Germ cell tumors[105] and early stage solid tumors which were once incurable have become curable malignancies now. Immunotherapies have already proven efficient in leukemia, bladder cancer and various skin cancer. For the future, research is promising in the field of physical oncology.[106]

- Survival of cancer has significantly improved over the past years[quantify] due to improved screening, diagnostic methods and treatment options with targeted therapy.

- Large multi-centric Phase III randomised controlled clinical trials by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast & Bowel Project (NSABP)[107] Medical Research Council (MRC),[108] the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC),[109] and National Cancer Institute (NCI) have contributed significantly to the improvement in survival.

See also[]

- American Cancer Society

- American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network

- American Cancer Society Center

- American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Cancer Research UK

- Comparative oncology

- National Cancer Institute

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- Oncometabolism

- Programme of Action for Cancer Therapy

- Tumour heterogeneity

- Warburg effect (oncology)

References[]

- ^ Maureen McCutcheon. Where Have My Eyebrows Gone?. Cengage Learning, 2001. ISBN 0766839346. Page 5.

- ^ Types of Oncologists, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

- ^ Janssen, Diederik F. (March 2021). "Oncology: etymology of the term". Medical Oncology. 38 (3): 22. doi:10.1007/s12032-021-01471-4. ISSN 1357-0560. PMID 33558951. S2CID 231849990.

- ^ Stein, C. J.; Colditz, G. A. (2004-01-26). "Modifiable risk factors for cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 90 (2): 299–303. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601509. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 2410150. PMID 14735167.

- ^ Hristova, L.; Hakama, M. (1997-01-01). "Effect of screening for cancer in the Nordic countries on deaths, cost and quality of life up to the year 2017". Acta Oncologica. 36 Suppl 9: 1–60. ISSN 0284-186X. PMID 9143316.

- ^ Forbes, J. F. (1982-08-01). "Multimodality treatment of cancer". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 52 (4): 341–346. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06005.x. ISSN 0004-8682. PMID 6956307.

- ^ Bristow, Robert E.; Chang, Jenny; Ziogas, Argyrios; Campos, Belinda; Chavez, Leo R.; Anton-Culver, Hoda (2015-05-01). "Impact of National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Centers on ovarian cancer treatment and survival". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 220 (5): 940–950. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.01.056. ISSN 1879-1190. PMC 5145798. PMID 25840536.

- ^ Croke, J.M.; El-Sayed, S. (2012-08-01). "Multidisciplinary management of cancer patients: chasing a shadow or real value? An overview of the literature". Current Oncology. 19 (4): e232–e238. doi:10.3747/co.19.944. ISSN 1198-0052. PMC 3410834. PMID 22876151.

- ^ "Medical Oncology". American Medical Association. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Zheng, Ying; Lei, Fang; Liu, Bao (December 14, 2019). "Cancer Diagnosis Disclosure and Quality of Life in Elderly Cancer Patients". Healthcare. 7 (4): 163. doi:10.3390/healthcare7040163. PMC 6956195. PMID 31847309.

- ^ Baile, W. F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E. A.; Kudelka, A. P. (March 2, 2000). "SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer". The Oncologist. 5 (4): 302–311. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. PMID 10964998.

- ^ "Ask the Hematologist: SPIKES Protocol For Delivering Bad News to Patients". www.hematology.org. July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Cancers linked to tobacco use make up 40% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. January 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Tobacco". National Cancer Institute. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ^ "Alcohol". National Cancer Institute. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ^ "Obesity". National Cancer Institute. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ^ "Age". National Cancer Institute. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ^ Gøtzsche, Peter C.; Jørgensen, Karsten Juhl (2013-01-01). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- ^ Behtash, Nadereh; Mehrdad, Nili (2006-12-01). "Cervical cancer: screening and prevention". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 7 (4): 683–686. ISSN 1513-7368. PMID 17250453.

- ^ Winawer, Sidney; Fletcher, Robert; Rex, Douglas; Bond, John; Burt, Randall; Ferrucci, Joseph; Ganiats, Theodore; Levin, Theodore; Woolf, Steven (2003-02-01). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology. 124 (2): 544–560. doi:10.1053/gast.2003.50044. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 12557158.

- ^ Humphrey, Linda L.; Deffebach, Mark; Pappas, Miranda; Baumann, Christina; Artis, Kathryn; Mitchell, Jennifer Priest; Zakher, Bernadette; Fu, Rongwei; Slatore, Christopher G. (2013-09-17). "Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (6): 411–420. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690. ISSN 1539-3704. PMID 23897166.

- ^ "Symptoms of Breast Cancer | Breastcancer.org". Breastcancer.org. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Endometrial Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Cervical Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Olson, S. H.; Mignone, L.; Nakraseive, C.; Caputo, T. A.; Barakat, R. R.; Harlap, S. (2001-08-01). "Symptoms of ovarian cancer". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 98 (2): 212–217. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01457-0. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 11506835. S2CID 45300927.

- ^ a b Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Lung Cancer: Symptoms - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Mehanna, H.; Paleri, V.; West, C. M. L.; Nutting, C. (2010-01-01). "Head and neck cancer—Part 1: Epidemiology, presentation, and prevention". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 341: c4684. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4684. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 20855405. S2CID 6950162.

- ^ Snyder, H.; Robinson, K.; Shah, D.; Brennan, R.; Handrigan, M. (1993-06-01). "Signs and symptoms of patients with brain tumors presenting to the emergency department". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11 (3): 253–258. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(93)90042-6. ISSN 0736-4679. PMID 8340578.

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Thyroid Cancer: Symptoms - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Esophageal Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Stomach Cancer (Gastric Cancer): Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Colon Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Adult Primary Liver Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Holly, Elizabeth A.; Chaliha, Indranushi; Bracci, Paige M.; Gautam, Manjushree (2004-06-01). "Signs and symptoms of pancreatic cancer: a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco Bay area". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2 (6): 510–517. doi:10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00171-5. ISSN 1542-3565. PMID 15181621.

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: Symptoms - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Renal Cell Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Shephard, Elizabeth A.; Stapley, Sally; Neal, Richard D.; Rose, Peter; Walter, Fiona M.; Hamilton, William T. (2012-09-01). "Clinical features of bladder cancer in primary care". The British Journal of General Practice. 62 (602): e598–604. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X654560. ISSN 1478-5242. PMC 3426598. PMID 22947580.

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Prostate Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Testicular Cancer: Symptoms – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2016-01-17.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Clohisy, Denis R.; Mantyh, Patrick W. (2003-10-01). "Bone cancer pain". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 415 (415 Suppl): S279–288. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000093059.96273.56. ISSN 0009-921X. PMID 14600620. S2CID 46254928.

- ^ Vuckovic, J.; Zemunik, T.; Forenpoher, G.; Knezevic, N.; Stula, N.; Dubravcic, M.; Capkun, V. (1994-04-01). "Prognostic value of B-symptoms in low-grade non-hodgkin's lymphomas". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 13 (3–4): 357–358. doi:10.3109/10428199409056302. ISSN 1042-8194. PMID 8049656.

- ^ Givan, Alice L. (2011-01-01). "Flow cytometry: an introduction". Flow Cytometry Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. 699. pp. 1–29. doi:10.1007/978-1-61737-950-5_1. ISBN 978-1-61737-949-9. PMID 21116976.

- ^ Mrózek, Krzysztof; Heerema, Nyla A.; Bloomfield, Clara D. (2004-06-01). "Cytogenetics in acute leukemia". Blood Reviews. 18 (2): 115–136. doi:10.1016/S0268-960X(03)00040-7. ISSN 0268-960X. PMID 15010150.

- ^ Bacher, Ulrike; Schnittger, Susanne; Haferlach, Claudia; Haferlach, Torsten (2009-01-01). "Molecular diagnostics in acute leukemias". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 47 (11): 1333–1341. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2009.324. ISSN 1437-4331. PMID 19817644. S2CID 28772535.

- ^ Eberle, Franziska C.; Mani, Haresh; Jaffe, Elaine S. (2009-04-01). "Histopathology of Hodgkin's lymphoma". Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 15 (2): 129–137. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819e31cf. ISSN 1528-9117. PMID 19390308. S2CID 12943441.

- ^ Rao, I. Satish (2010-01-01). "Role of immunohistochemistry in lymphoma". Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 31 (4): 145–147. doi:10.4103/0971-5851.76201. ISSN 0971-5851. PMC 3089924. PMID 21584221.

- ^ Arber, Daniel A. (2000-11-01). "Molecular Diagnostic Approach to Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2 (4): 178–190. doi:10.1016/s1525-1578(10)60636-8. ISSN 1525-1578. PMC 1906917. PMID 11232108.

- ^ Hande, K. R.; Garrow, G. C. (1993-02-01). "Acute tumor lysis syndrome in patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". The American Journal of Medicine. 94 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(93)90174-n. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 8430709.

- ^ D'souza, Maria M; Jaimini, Abhinav; Bansal, Abhishek; Tripathi, Madhavi; Sharma, Rajnish; Mondal, Anupam; Tripathi, Rajendra Prashad (2013-01-01). "FDG-PET/CT in lymphoma". The Indian Journal of Radiology & Imaging. 23 (4): 354–365. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.125626. ISSN 0971-3026. PMC 3932580. PMID 24604942.

- ^ Kumar, Suneet; Rau, Aarathi R.; Naik, Ramadas; Kini, Hema; Mathai, Alka M.; Pai, Muktha R.; Khadilkar, Urmila N. (2009-09-01). "Bone marrow biopsy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a morphological study". Indian Journal of Pathology & Microbiology. 52 (3): 332–338. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.54987. ISSN 0974-5130. PMID 19679954.

- ^ Pillai, R.; Kannan, S.; Chandran, G. J. (1993-04-01). "The immunohistochemistry of solid tumours: potential problems for new laboratories". The National Medical Journal of India. 6 (2): 71–75. ISSN 0970-258X. PMID 8477213.

- ^ Franzius, C. (2010-08-01). "FDG-PET/CT in pediatric solid tumors". The Quarterly Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 54 (4): 401–410. ISSN 1824-4785. PMID 20823808.

- ^ a b Bassetto, M. A.; Franceschi, T.; Lenotti, M.; Parise, G.; Pancheri, F.; Sabbioni, R.; Zaninelli, M.; Cetto, G. L. (1994-01-01). "AFP and HCG in germ cell tumors". The International Journal of Biological Markers. 9 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1177/172460089400900106. ISSN 0393-6155. PMID 7519651. S2CID 26561336.

- ^ Barone, C.; Astone, A.; Cassano, A.; Garufi, C.; Astone, P.; Grieco, A.; Noviello, M. R.; Ricevuto, E.; Albanese, C. (1990-01-01). "Advanced colon cancer: staging and prognosis by CEA test". Oncology. 47 (2): 128–132. doi:10.1159/000226804. ISSN 0030-2414. PMID 2314825.

- ^ Scholler, Nathalie; Urban, Nicole (2007-12-01). "CA125 in Ovarian Cancer". Biomarkers in Medicine. 1 (4): 513–523. doi:10.2217/17520363.1.4.513. ISSN 1752-0363. PMC 2872496. PMID 20477371.

- ^ Gjertson, Carl K.; Albertsen, Peter C. (2011-01-01). "Use and assessment of PSA in prostate cancer". The Medical Clinics of North America. 95 (1): 191–200. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.024. ISSN 1557-9859. PMID 21095422.

- ^ a b PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). "Breast Cancer Treatment (Adult) (PDQ®): Patient Version". Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389406.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389493.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389334.

- ^ Aletti, Giovanni D.; Gallenberg, Mary M.; Cliby, William A.; Jatoi, Aminah; Hartmann, Lynn C. (2007-06-01). "Current management strategies for ovarian cancer". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (6): 751–770. doi:10.4065/82.6.751. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 17550756.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389355.

- ^ Argiris, Athanassios; Karamouzis, Michalis V.; Raben, David; Ferris, Robert L. (2008-05-17). "Head and neck cancer". Lancet. 371 (9625): 1695–1709. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60728-X. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 7720415. PMID 18486742. S2CID 31972883.

- ^ Regalbuto, Concetto; Frasca, Francesco; Pellegriti, Gabriella; Malandrino, Pasqualino; Marturano, Ilenia; Di Carlo, Isidoro; Pezzino, Vincenzo (2012-10-01). "Update on thyroid cancer treatment". Future Oncology (London, England). 8 (10): 1331–1348. doi:10.2217/fon.12.123. ISSN 1744-8301. PMID 23130931.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). "Esophageal Cancer Treatment (Adult) (PDQ®): Health Professional Version". Esophageal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389338.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Gastric Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389328.

- ^ Wagner, Anna Dorothea; Syn, Nicholas LX; Moehler, Markus; Grothe, Wilfried; Yong, Wei Peng; Tai, Bee-Choo; Ho, Jingshan; Unverzagt, Susanne (2017-08-29). "Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD004064. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004064.pub4. PMC 6483552. PMID 28850174.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389319.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Rectal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389402.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Adult Primary Liver Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389251.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). "Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (Adult) (PDQ®): Patient Version". Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389396.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Skin Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389265.

- ^ Jonasch, Eric (2015-05-01). "Kidney cancer: current and novel treatment options". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 13 (5 Suppl): 679–681. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2015.0202. ISSN 1540-1413. PMID 25995429.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Bladder Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389399.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389353.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Testicular Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389220.

- ^ "Osteosarcoma and MFH of Bone Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002-01-01). Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389473.

- ^ "Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ "Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ "Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ "Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ "Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Treatment". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ Kennedy, B. J. (1997-12-01). "Medical oncology as a discipline". Oncology. 54 (6): 459–462. doi:10.1159/000227603. ISSN 0030-2414. PMID 9394841.

- ^ a b "Types of Oncologists". Cancer.Net : American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). 2011-05-09. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "What is clinical oncology? | the Royal College of Radiologists".

- ^ Natarajan, Sundaram (2015-02-01). "Ocular oncology – A multidisciplinary specialty". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 63 (2): 91. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.154364. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 4399140. PMID 25827536.

- ^ Manganaris, Argyris; Black, Myles; Balfour, Alistair; Hartley, Christopher; Jeannon, Jean-Pierre; Simo, Ricard (2009-07-01). "Sub-specialty training in head and neck surgical oncology in the European Union". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 266 (7): 1005–1010. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0832-4. ISSN 1434-4726. PMID 19015865. S2CID 20700214.

- ^ Harish, Krishnamachar; Kirthi Koushik, Agrahara Sreenivasa (2015-05-01). "Multidisciplinary teams in thoracic oncology-from tragic to strategic". Annals of Translational Medicine. 3 (7): 89. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.01.31. ISSN 2305-5839. PMC 4430737. PMID 26015931.

- ^ Mulder, Chris Jacob Johan; Peeters, Marc; Cats, Annemieke; Dahele, Anna; Droste, Jochim Terhaar sive (2011-03-07). "Digestive oncologist in the gastroenterology training curriculum". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 17 (9): 1109–1115. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1109. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 3063902. PMID 21556128.

- ^ Weber, Kristy L.; Gebhardt, Mark C. (2003-04-01). "What's new in musculoskeletal oncology". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 85-A (4): 761–767. doi:10.2106/00004623-200304000-00029. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 12672857.

- ^ Bukowski, Ronald M. (2011-10-10). "Genitourinary Oncology: Current Status and Future Challenges". Frontiers in Oncology. 1: 32. doi:10.3389/fonc.2011.00032. ISSN 2234-943X. PMC 3355990. PMID 22649760.

- ^ Benedetti-Panici, P.; Angioli, R. (2004-01-01). "Gynecologic oncology specialty". European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 25 (1): 25–26. ISSN 0392-2936. PMID 15053057.

- ^ Wolff, J. A. (1991-06-01). "History of pediatric oncology". Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 8 (2): 89–91. doi:10.3109/08880019109033436. ISSN 0888-0018. PMID 1863546.

- ^ Shaw, Peter H.; Reed, Damon R.; Yeager, Nicholas; Zebrack, Bradley; Castellino, Sharon M.; Bleyer, Archie (April 2015). "Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Oncology in the United States: A Specialty in Its Late Adolescence". Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 37 (3): 161–169. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000318. ISSN 1536-3678. PMID 25757020. S2CID 27695404.

- ^ Mkrtchyan, L. N. (2010-06-01). "On a new strategy of preventive oncology". Neurochemical Research. 35 (6): 868–874. doi:10.1007/s11064-009-0110-x. ISSN 1573-6903. PMID 20119639. S2CID 582313.

- ^ Vijaykumar, D. K.; Anupama, R.; Gorasia, Tejal Kishor; Beegum, T. R. Haleema; Gangadharan, P. (2012-01-01). "Geriatric oncology: The need for a separate subspecialty". Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 33 (2): 134–136. ISSN 0971-5851. PMC 3439792. PMID 22988358.

- ^ Epstein, A. S.; Morrison, R. S. (2012-04-01). "Palliative oncology: identity, progress, and the path ahead". Annals of Oncology. 23 Suppl 3: 43–48. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds087. ISSN 1569-8041. PMC 3493143. PMID 22628415.

- ^ Jenkins, Robert (2001-04-01). "Principles of Molecular Oncology". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (4): 1068. doi:10.1086/319526. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1275628.

- ^ Breen, Matthew (2009-08-01). "Update on genomics in veterinary oncology". Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 24 (3): 113–121. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2009.03.002. ISSN 1938-9736. PMC 2754151. PMID 19732729.

- ^ Ghosh, AK; Walker, JM (2 January 2017). "Cardio-oncology". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 78 (1): C11–C13. doi:10.12968/hmed.2017.78.1.C11. PMID 28067553.

- ^ "Background".

- ^ Martí-Bonmatí, Luis; Alberich-Bayarri, Ángel; Ladenstein, Ruth; Blanquer, Ignacio; Segrelles, J. Damian; Cerdá-Alberich, Leonor; Gkontra, Polyxeni; Hero, Barbara; García-Aznar, J. M.; Keim, Daniel; Jentner, Wolfgang; Seymour, Karine; Jiménez-Pastor, Ana; González-Valverde, Ismael; Martínez De Las Heras, Blanca; Essiaf, Samira; Walker, Dawn; Rochette, Michel; Bubak, Marian; Mestres, Jordi; Viceconti, Marco; Martí-Besa, Gracia; Cañete, Adela; Richmond, Paul; Wertheim, Kenneth Y.; Gubala, Tomasz; Kasztelnik, Marek; Meizner, Jan; Nowakowski, Piotr; et al. (2020). "PRIMAGE project: predictive in silico multiscale analytics to support childhood cancer personalised evaluation empowered by imaging biomarkers". European Radiology Experimental. 4 (1): 22. doi:10.1186/s41747-020-00150-9. PMC 7125275. PMID 32246291.

- ^ Hill, J. M.; Meehan, K. R. (1999-09-01). "Chronic myelogenous leukemia. Curable with early diagnosis and treatment". Postgraduate Medicine. 106 (3): 149–152, 157–159. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.09.686. ISSN 0032-5481. PMID 10494272.

- ^ Armitage, James O. (2012-02-01). "My Treatment Approach to Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (2): 161–171. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.007. ISSN 0025-6196. PMC 3497705. PMID 22305028.

- ^ Masters, John R. W.; Köberle, Beate (2003-07-01). "Curing metastatic cancer: lessons from testicular germ-cell tumours". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 3 (7): 517–525. doi:10.1038/nrc1120. ISSN 1474-175X. PMID 12835671. S2CID 41441023.

- ^ "Research Priorities to Accelerate Progress Against Cancer". American Society of Clinical Oncology. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP)". www.nsabp.pitt.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ^ Medical Research Council, M. R. C. (July 5, 2018). "Home". mrc.ukri.org.

- ^ "EORTC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer". EORTC.

Further reading[]

- Watson, Ian R.; Takahashi, Koichi; Futreal, P. Andrew; Chin, Lynda (2013). "Emerging patterns of somatic mutations in cancer". Nat Rev Genet. 14 (10): 703–718. doi:10.1038/nrg3539. PMC 4014352. PMID 24022702.

- Meyerson, Matthew; Gabriel, Stacey; Getz, Gad (2010). "Advances in understanding cancer genomes through second-generation sequencing". Nat Rev Genet. 11 (10): 685–696. doi:10.1038/nrg2841. PMID 20847746. S2CID 2544266.

- Katsanis, Sara Huston; Katsanis, Nicholas (2013). "Molecular genetic testing and the future of clinical genomics". Nat Rev Genet. 14 (6): 415–426. doi:10.1038/nrg3493. PMC 4461364. PMID 23681062.

- Mardis, Elaine R. (2012). "Applying next-generation sequencing to pancreatic cancer treatment". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9 (8): 477–486. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.126. PMID 22751458. S2CID 9981262.

- Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2011). The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-725092-9.

- Vickers, Andrew (1 March 2004). "Alternative Cancer Cures: "Unproven" or "Disproven"?". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 54 (2): 110–118. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.521.2180. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110. PMID 15061600. S2CID 35124492.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oncology. |

- "Comprehensive Cancer Information". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- "NCCN - Evidence-Based Cancer Guidelines, Oncology Drug Compendium, Oncology Continuing Medical Education". National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- "European Society for Medical Oncology | ESMO". www.esmo.org. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- Oncology