Penghusuchus

| Penghusuchus Temporal range: Late Miocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

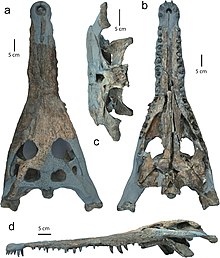

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Genus: | †Penghusuchus Shan et al., 2009 |

| Type species | |

| †Penghusuchus pani Shan et al., 2009

| |

Penghusuchus is an extinct genus of gavialid crocodylian. It is known from a skeleton found in Upper Miocene rocks of Penghu Island, off Taiwan. It may be related to two other fossil Asian gavialids: Maomingosuchus petrolica of southeastern China and Toyotamaphimeia machikanensis of Japan. The taxon was described in 2009 by Shan and colleagues; the type species is P. pani.[2]

Below is a cladogram based morphological studies comparing skeletal features that shows Penghusuchus as a member of Tomistominae, related to the false gharial:[3]

| Crocodylidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on morphological studies of extinct taxa, the tomistomines (including the living false gharial) were long thought to be classified as crocodiles and not closely related to gavialoids.[4] However, recent molecular studies using DNA sequencing have consistently indicated that the false gharial (Tomistoma) (and by inference other related extinct forms in Tomistominae) actually belong to Gavialoidea (and Gavialidae).[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Below is a cladogram from a 2018 tip dating study by Lee & Yates simultaneously using morphological, molecular (DNA sequencing), and stratigraphic (fossil age) data that shows Penghusuchus as a gavialid, related to both the gharial and the false gharial:[10]

| Gavialidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[]

- ^ Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ. 9: e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMC 8428266. PMID 34567843.

- ^ Shan, Hsi-yin; Wu, Xiao-chun; Cheng, Yen-nien; Sato, Tamaki (2009). "A new tomistomine (Crocodylia) from the Miocene of Taiwan". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 46 (7): 529–555. Bibcode:2009CaJES..46..529S. doi:10.1139/E09-036.

- ^ Iijima, Masaya; Momohara, Arata; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Hayashi, Shoji; Ikeda, Tadahiro; Taruno, Hiroyuki; Watanabe, Katsunori; Tanimoto, Masahiro; Furui, Sora (2018-05-01). "Toyotamaphimeia cf. machikanensis (Crocodylia, Tomistominae) from the Middle Pleistocene of Osaka, Japan, and crocodylian survivorship through the Pliocene-Pleistocene climatic oscillations". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 496: 346–360. Bibcode:2018PPP...496..346I. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.02.002. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Brochu, C.A.; Gingerich, P.D. (2000). "New tomistomine crocodylian from the Middle Eocene (Bartonian) of Wadi Hitan, Fayum Province, Egypt". University of Michigan Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. 30 (10): 251–268.

- ^ Harshman, J.; Huddleston, C. J.; Bollback, J. P.; Parsons, T. J.; Braun, M. J. (2003). "True and false gharials: A nuclear gene phylogeny of crocodylia" (PDF). Systematic Biology. 52 (3): 386–402. doi:10.1080/10635150309323. PMID 12775527.

- ^ Gatesy, Jorge; Amato, G.; Norell, M.; DeSalle, R.; Hayashi, C. (2003). "Combined support for wholesale taxic atavism in gavialine crocodylians" (PDF). Systematic Biology. 52 (3): 403–422. doi:10.1080/10635150309329. PMID 12775528.

- ^ Willis, R. E.; McAliley, L. R.; Neeley, E. D.; Densmore Ld, L. D. (June 2007). "Evidence for placing the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) into the family Gavialidae: Inferences from nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 43 (3): 787–794. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.005. PMID 17433721.

- ^ Gatesy, J.; Amato, G. (2008). "The rapid accumulation of consistent molecular support for intergeneric crocodylian relationships". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 48 (3): 1232–1237. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.009. PMID 18372192.

- ^ Erickson, G. M.; Gignac, P. M.; Steppan, S. J.; Lappin, A. K.; Vliet, K. A.; Brueggen, J. A.; Inouye, B. D.; Kledzik, D.; Webb, G. J. W. (2012). Claessens, Leon (ed.). "Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31781. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731781E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031781. PMC 3303775. PMID 22431965.

- ^ a b Michael S. Y. Lee; Adam M. Yates (27 June 2018). "Tip-dating and homoplasy: reconciling the shallow molecular divergences of modern gharials with their long fossil". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1881). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1071. PMC 6030529. PMID 30051855.

- ^ Hekkala, E.; Gatesy, J.; Narechania, A.; Meredith, R.; Russello, M.; Aardema, M. L.; Jensen, E.; Montanari, S.; Brochu, C.; Norell, M.; Amato, G. (2021-04-27). "Paleogenomics illuminates the evolutionary history of the extinct Holocene "horned" crocodile of Madagascar, Voay robustus". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 505. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 8079395. PMID 33907305.

- Gavialidae

- Miocene crocodylomorphs

- Miocene reptiles of Asia

- Prehistoric pseudosuchian genera

- Prehistoric archosaur stubs