Persian Constitution of 1906

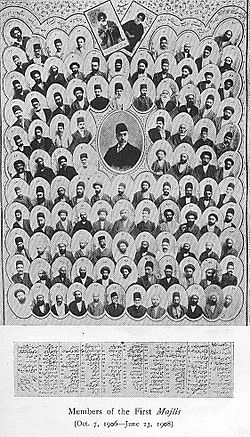

Members of the First Majlis (October 7, 1906 — June 23, 1908). The central photograph is that of Morteza Gholi Khan Hedayat, Sani-ol Douleh, the first Chairman of the First Majlis. He had been for seven months the Finance Minister when he was assassinated on 6 February 1911 by two Georgian nationals in Tehran.[1] | |

| Location | Qajar Iran |

|---|---|

| Media type | Constitution |

The Persian Constitution of 1906[2][3][4] (Persian: قانون اساسی مشروطه, romanized: Qanun-e Asasi-ye Mishirutâh), was the first constitution of the Sublime State of Persia (Qajar Iran), resulting from the Persian Constitutional Revolution and it was written by Hassan Pirnia, Hossein Pirnia, and Ismail Mumtaz, among others.[5] It divides into five chapters with many articles that developed over several years. The Quran was the foundation of this constitution while Belgian constitution served as a partial model for the document.[6]

The electoral and fundamental laws of 1906[]

The electoral and fundamental laws of 1906 established the electoral system and the internal frameworks of the Majlis (Parliament) and the Senate.

By the royal proclamation of August 5, 1906, Mozzafar al-Din Shah created this first constitution "for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Persia." Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar is credited with chapters 4 and 5.

The electoral law of September 9, 1906[]

The electoral law of September 9, 1906 defined the regulations for the Elections to the Majlis.

Disenfranchised[]

Article 3 of this chapter stated that (1) women, (2) foreigners, (3) those under 25, (4) "persons notorious for mischievous opinions," (5) those with a criminal record, (6) active military personnel, and a few other groups are not permitted to vote.

Election qualifications[]

Article 4 stated that the elected must be (1) fully literate in Persian, (2) "they must be Iranian subjects of Iranian extraction," (3) "be locally known," (4) "not be in government employment," (5) be between 30 and 70 years old, and (6) "have some insight into affairs of State."

Article 7 asserted, "Each elector has one vote and can only vote in one [social] class."

The fundamental laws of December 30, 1906[]

The fundamental laws of December 30, 1906 defined the role of the Majlis in the system and its framework. It further defined a bicameral legislature. Article 1 established the National Consultative Assembly[7] based "on justice." Article 43 stated, "There shall be constituted another Assembly, entitled the Senate."

The supplementary fundamental laws of October 7, 1907[]

This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (November 2013) |

The supplementary fundamental laws of October 7, 1907 established the charter of rights and overall system of governance.

The Supplementary Fundamental Laws of October 7, 1907 consist of ten sections:[8] 1. General Dispositions 2. Rights of the Persian Nation 3. Powers of the Realm 4. Rights of Members of the Assembly 5. Rights of Persian Throne 6. Concerning the Ministers 7. Powers of the Tribunal of Justice 8. Provincial and Departmental Councils (anjumans) 9. Concerning the Finances 10. The Army

The original Fundamental Law, containing 51 Articles, was promulgated on Dhu’l-Qu’da 14, A.H. 1324 (December 30, 1906) by Muzaffaru’d-Din Shah, who died just 4 days later. The following supplementary laws were ratified by his son and successor Shah Muhammad ‘Ali on Sha’ban 29, A.H. 1325 (October 7, 1907)

General Dispositions[]

Article 1 and 2 of the laws, established Islam as the official religion of Persia/Iran, and specified that all laws of the nation must be approved by a committee of Shi'a clerics. Later, these two articles were mainly ignored by the Pahlavis, which sometimes resulted in anger and uprising of clerics and religious masses: (See: Pahlavis and non-Islamic policies)

Articles 3-7 under the General Dispositions discuss the logistics of borders, flag specifications and Tehran as the capital of the country. They also elaborate on the property rights of foreign nationals in Iran as well as the inability to suspend the principles of the constitution.[9]

Rights of the Iranian Nation[]

In the "Rights of the Iranian Nation," articles 8-25 discuss an array of rights inherent to all citizens of Iran. These rights include personal and property rights as well as freedom of expression and censorship. They briefly touch on the rights of citizenship and to move freely within the country.[10]

Powers of the Realm[]

This section of the Supplementary Fundamental Laws of October 7, 1907 begins by stating the following:

The powers of the realm are all derived from the people; and the Fundamental Law regulates the employment of those powers.

Article 27 discussed the three categories that the power of the realm is divided into as:

First, the legislative power which is specially concerned with the making or amelioration of laws. This power is derived from His Imperial Majesty, the National Consultative Assembly, and the Senate, of which three sources each has the right to introduce laws, provided that the continuance thereof be dependent on their not being at variance with the standards of the ecclesiastical law, and on its approval by the Members of the two Assemblies, and the Royal ratification. The enacting and approval of laws connected with the revenue and expenditure of the kingdom are, however, specially assigned to the National Consultative Assembly. The explanation and interpretation of the laws are, moreover, amongst the special functions of the above-mentioned assembly.

Second, the judicial power, by which is meant the determining of rights. This power belongs exclusively to the ecclesiastical tribunals in matters connected with the ecclesiastical law, and to the civil tribunals in matters connected with ordinary law.

Third, the executive power, which appertains to the King, that is to say, the laws and ordinances are carried out by the Ministers and State officials in the august name of His Imperial Majesty in such manner as the Law Defines.

The remaining articles entail a permanent distinction between the three powers as well as their relativity in each province, department and district.[11]

Rights of Members of the Assembly[]

This section includes the roles of the National Consultative Assembly and the Senate and the stipulations for membership within the two branches of government.[12]

Rights of the Persian Throne[]

In the Rights of the Persian Throne, the section begins with several articles outlining the duties of the Shah and the logistics of the throne. These include the process of succession to the throne, ascending to the throne and how to deal with instances issues like death.

It further discusses the duties of the Shah like the appointment and dismissal of Ministers and The granting of military rank, decoration and other honorary distinctions. The shah also commands the military and has the final say on whether or not to wage war.

This sections concludes in Article 57 by underlining the precise degree of power that the Shah obtains saying:

. The Royal prerogatives and powers are only those explicitly mentioned in the present Constitutional Law.

Concerning the Ministers[]

Articles 58-70 comment on the duties and laws regarding the Ministers. This section also helps to establish the specific roles that Ministers play in the government.

Several articles talk specifically about how Ministers are appointed as well as how they are held accountable for their delinquencies.

Powers of the Tribunal of Justice[]

This section begins by stating the purpose for the Ministry of Justice with article 71:

*ART. 71.

- The Supreme Ministry of Justice and the judicial tribunals are the places officially destine for the redress of public grievances, while judgement in all matters falling within the scope of the Ecclesiastical Law is vested in just mujtahids possessing the necessary qualifications.

Articles 72-82 continue on to discuss the instructions for dealing with public disputes and inquiries as well as the legal aspects of carrying out justice in regards to law violations. Several articles explain the rules for all proceedings of tribunals declaring that they must be public and that all decisions must be based on reason and supported by proof in accordance to the law.

In articles 83-89, the issue of appointment is addressed and explained in regards to the Public Prosecutor and the members of the judicial tribunals, corroborating with the laws set forth.[14]

Provincial and Departmental Councils (anjumans)[]

The various Provincial and Departmental Councils are discussed in this section, establishing the special regulations for the different branches.

The fundamental laws regulating these assemblies includes the election of the members of the provincial and departmental councils, the supervision over all reforms connected with the public advantage, and duties of the expenditure for the individual councils.[15]

Concerning the Finances[]

The regulations and management of finances is provided in articles 94-103. These articles include laws regarding taxes, tax exemptions, the set laws regarding the approval of the budget as well as the role of the Financial Commission.

The Financial Commission's role is:

to inspect and analyse the accounts of the Department of Finance and to liquidate the accounts of all debtors and creditors of the Treasury.

The section concludes with the idea that the institution and organization of the Financial Commission must be in accordance with the Law.[16]

The Army[]

The last section of the Supplementary Fundamental Laws of October 7, 1907 is the Army. This sections outlines all elements of recruitment of troops, the duties and rights of the military, and the promotion of military personnel. It further discusses the budget of the military which is determined by the National Consultative Assembly each year, and rights regarding military personnel.

The Supplementary Fundamental Laws of October 7, 1907 conclude with the following statements:[17]

"In the Name of God, blessed and exalted is He."

"The complementary provisions of the Fundamental Code of Laws have been perused and are correct. Please God, our Royal Person will observe and regard all of them. Our sons and successors also will, please God, confirm these sacred laws and principles.

The Law only says that the laws mustn't be against Islam, but not that the laws have to be Islamic. Laws can indeed be un-Islamic and not be at variance with any specified Islamic law. The Constitutional Revolution had a role in suppressing the power that the clergy and the religion had. The Revolution gave rights to minorities such as Zoroastrians, Christians and Jews.[18]

See also[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Attempts at Constitutionalization in Iran

- Iran Constituent Assembly, 1949

- 1963 Iranian constitutional referendum

- Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran

References and notes[]

- ^ W. Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia, 3rd printing (T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1913), pp. 48, 119, 179. According to Shuster (p. 48), "Five days later [measured from February 1st] the Persian Minister of Finance, was shot and killed in the streets of Teheran by two Georgians, who also succeeded in wounding four of the Persian police before they were captured. The Russian consular authorities promptly refused to allow these men to be tried by the Persian Government, and took them out of the country under Russian protection, claiming that they would be suitably punished."

See also: , The retreat by the Parliament in overseeing the financial matters is a retreat of democracy, in Persian, Mardom-Salari, No. 1734, 20 Bahman 1386 AH (9 February 2008), "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2007-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Tilmann J. Röder, The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, in: Rainer Grote and Tilmann J. Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2012), p. 321-3372. The article includes scientific English translation of the following documents: The Fundamental Law (Qanun-e Asasi-e Mashruteh) of the Iranian Empire of December 30, 1906 (p. 359-365); The Amendment of the Fundamental Law of the Iranian Empire of October 7, 1907 (p. 365-372).

- ^ * The Mashruteh Constitution of Iran (farsi). Berlin 2014. ISBN 9783844292923. (Details)

- ^ Recognizing the centennial anniversary Archived 2016-01-17 at the Wayback Machine 109th CONGRESS, 2d Session, H. RES. 942, 25 July 2006

- ^ For a modern English translation of the constitution and related laws see, Tilmann J. Röder, The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, in: Grote/Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2011).

- ^ Destrée, Annette. "BELGIAN-IRANIAN RELATIONS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- ^ This became known as the Islamic Consultative Assembly after the Islamic Revolution.

- ^ "Iran's 1906 Constitution". Foundation for Iranian Studies. Retrieved 2013-11-18.

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ http://fis-iran.org/en/resources/legaldoc/iranconstitution

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20071024144423/http://www.gozaar.org/template1.php?id=425. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading[]

- Massie, Eric; Afary, Janet (2019). "Iran's 1907 constitution and its sources: a critical comparison". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 46 (3): 464–480. doi:10.1080/13530194.2018.1425607. S2CID 149395330.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Persian Constitution of 1906. |

- Iran's 1906 Constitution and Its Supplement

- Constitution of Iran, 1906 (farsi)

- Constitutional Revolution from Iran Chamber Society

- Persian Constitutional Revolution

- Defunct constitutions

- Legal history of Iran

- Politics of Qajar Iran

- 1906 in Iran

- 1906 in law

- 20th century in Iran

- 1906 documents

- Constitutions of Iran

- 1900s in Islam