Phenology

Phenology is the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation).[1]

Examples include the date of emergence of leaves and flowers, the first flight of butterflies, the first appearance of migratory birds, the date of leaf colouring and fall in deciduous trees, the dates of egg-laying of birds and amphibia, or the timing of the developmental cycles of temperate-zone honey bee colonies. In the scientific literature on ecology, the term is used more generally to indicate the time frame for any seasonal biological phenomena, including the dates of last appearance (e.g., the seasonal phenology of a species may be from April through September).

Because many such phenomena are very sensitive to small variations in climate, especially to temperature, phenological records can be a useful proxy for temperature in historical climatology, especially in the study of climate change and global warming. For example, viticultural records of grape harvests in Europe have been used to reconstruct a record of summer growing season temperatures going back more than 500 years.[2][3] In addition to providing a longer historical baseline than instrumental measurements, phenological observations provide high temporal resolution of ongoing changes related to global warming.[4][5]

Etymology[]

The word is derived from the Greek φαίνω (phainō), "to show, to bring to light, make to appear"[6] + λόγος (logos), amongst others "study, discourse, reasoning"[7] and indicates that phenology has been principally concerned with the dates of first occurrence of biological events in their annual cycle.

The term was first used by Charles François Antoine Morren, a professor of Botany at the University of Liège (Belgium).[8] Morren was a student of Adolphe Quetelet. Quetelet made plant phenological observations at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels. He is considered "one of 19th century trendsetters in these matters."[9] In 1839 he started his first observations and created a network over Belgium and Europe that reached a total of about 80 stations in the period 1840-1870.

Morren participated in 1842 and 1843 in Quetelets 'Observations of Periodical Phenomena' (Observations des Phénomènes périodiques),[10] and at first suggested to mention the observations concerning botanical phenomena 'anthochronological observations'. That term had already been used in 1840 by .

But 16 December 1849 Morren used the term 'phenology' for the first time in a public lecture at the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels,[11][12] to describe “the specific science which has the goal to know the ‘’manifestation of life ruled by the time’’.”[13]

It would take four more years before Morren first published “phenological memories”.[14] That the term was not really common in the decades to follow may be shown by an article in The Zoologist of 1899. The article describes an ornithological meeting in Sarajevo, where 'questions of Phaenology' were discussed. A footnote by the Editor, William Lucas Distant, says: “This word is seldom used, and we have been informed by a very high authority that it may be defined as "Observational Biology," and as applied to birds, as it is here, may be taken to mean the study or science of observations on the appearance of birds.”[15]

Records[]

Historical[]

Observations of phenological events have provided indications of the progress of the natural calendar since ancient agricultural times. Many cultures have traditional phenological proverbs and sayings which indicate a time for action: "When the sloe tree is white as a sheet, sow your barley whether it be dry or wet" or attempt to forecast future climate: "If oak's before ash, you're in for a splash. If ash before oak, you're in for a soak". But the indications can be pretty unreliable, as an alternative version of the rhyme shows: "If the oak is out before the ash, 'Twill be a summer of wet and splash; If the ash is out before the oak, 'Twill be a summer of fire and smoke." Theoretically, though, these are not mutually exclusive, as one forecasts immediate conditions and one forecasts future conditions.

The North American Bird Phenology Program at USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center (PWRC) is in possession of a collection of millions of bird arrival and departure date records for over 870 species across North America, dating between 1880 and 1970. This program, originally started by Wells W. Cooke, involved over 3,000 observers including many notable naturalists of the time. The program ran for 90 years and came to a close in 1970 when other programs starting up at PWRC took precedence. The program was again started in 2009 to digitize the collection of records and now with the help of citizens worldwide, each record is being transcribed into a database which will be publicly accessible for use.

The English naturalists Gilbert White and William Markwick reported the seasonal events of more than 400 plant and animal species, Gilbert White in Selborne, Hampshire and William Markwick in Battle, Sussex over a 25-year period between 1768 and 1793. The data, reported in White's Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne[17] are reported as the earliest and latest dates for each event over 25 years; so annual changes cannot therefore be determined.

In Japan and China the time of blossoming of cherry and peach trees is associated with ancient festivals and some of these dates can be traced back to the eighth century. Such historical records may, in principle, be capable of providing estimates of climate at dates before instrumental records became available. For example, records of the harvest dates of the pinot noir grape in Burgundy have been used in an attempt to reconstruct spring–summer temperatures from 1370 to 2003;[18][19] the reconstructed values during 1787–2000 have a correlation with Paris instrumental data of about 0.75.

Modern[]

Great Britain[]

Robert Marsham, the founding father of modern phenological recording, was a wealthy landowner who kept systematic records of "Indications of spring" on his estate at Stratton Strawless, Norfolk, from 1736. These took the form of dates of the first occurrence of events such as flowering, bud burst, emergence or flight of an insect. Generations of Marsham's family maintained consistent records of the same events or "phenophases" over unprecedentedly long periods of time, eventually ending with the death of Mary Marsham in 1958, so that trends can be observed and related to long-term climate records. The data show significant variation in dates which broadly correspond with warm and cold years. Between 1850 and 1950 a long-term trend of gradual climate warming is observable, and during this same period the Marsham record of oak-leafing dates tended to become earlier.[20]

After 1960 the rate of warming accelerated, and this is mirrored by increasing earliness of oak leafing, recorded in the data collected by Jean Combes in Surrey. Over the past 250 years, the first leafing date of oak appears to have advanced by about 8 days, corresponding to overall warming on the order of 1.5 °C in the same period.

Towards the end of the 19th century the recording of the appearance and development of plants and animals became a national pastime, and between 1891 and 1948 the Royal Meteorological Society (RMS) organised a programme of phenological recording across the British Isles. Up to 600 observers submitted returns in some years, with numbers averaging a few hundred. During this period 11 main plant phenophases were consistently recorded over the 58 years from 1891–1948, and a further 14 phenophases were recorded for the 20 years between 1929 and 1948. The returns were summarised each year in the Quarterly Journal of the RMS as . Jeffree (1960) summarised the 58 years of data,[21] which show that flowering dates could be as many as 21 days early and as many as 34 days late, with extreme earliness greatest in summer-flowering species, and extreme lateness in spring-flowering species. In all 25 species, the timings of all phenological events are significantly related to temperature,[22][23] indicating that phenological events are likely to get earlier as climate warms.

The Phenological Reports ended suddenly in 1948 after 58 years, and Britain remained without a national recording scheme for almost 50 years, just at a time when climate change was becoming evident. During this period, individual dedicated observers made important contributions. The naturalist and author Richard Fitter recorded the First Flowering Date (FFD) of 557 species of British flowering plants in Oxfordshire between about 1954 and 1990. Writing in Science in 2002, Richard Fitter and his son Alistair Fitter found that "the average FFD of 385 British plant species has advanced by 4.5 days during the past decade compared with the previous four decades."[24][25] They note that FFD is sensitive to temperature, as is generally agreed, that "150 to 200 species may be flowering on average 15 days earlier in Britain now than in the very recent past" and that these earlier FFDs will have "profound ecosystem and evolutionary consequences". In Scotland, David Grisenthwaite meticulously recorded the dates he mowed his lawn since 1984. His first cut of the year was 13 days earlier in 2004 than in 1984, and his last cut was 17 days later, providing evidence for an earlier onset of spring and a warmer climate in general.[26][27][28]

National recording was resumed by Tim Sparks in 1998[29] and, from 2000,[30] has been led by citizen science project Nature's Calendar [2], run by the Woodland Trust and the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Latest research shows that oak bud burst has advanced more than 11 days since the 19th century and that resident and migrant birds are unable to keep up with this change.[31]

Continental Europe[]

In Europe, phenological networks are operated in several countries, e.g. Germany's national meteorological service operates a very dense network with approx. 1200 observers, the majority of them on a voluntary basis.[32] The Pan European Phenology (PEP) project is a database that collects phenological data from European countries. Currently 32 European meteorological services and project partners from across Europe have joined and supplied data.[33]

Other countries[]

There is a USA National Phenology Network [3] in which both professional scientists and lay recorders participate.

Many other countries such as Canada (Alberta Plantwatch [4] and Saskatchewan PlantWatch[34]), China and Australia[35][36] also have phenological programs.

In eastern North America, almanacs are traditionally used[by whom?] for information on action phenology (in agriculture), taking into account the astronomical positions at the time. William Felker has studied phenology in Ohio, US, since 1973 and now publishes "Poor Will's Almanack", a phenological almanac for farmers (not to be confused with a late 18th-century almanac by the same name).

In the Amazon rainforests of South America, the timing of leaf production and abscission has been linked to rhythms in gross primary production at several sites.[37][38] Early in their lifespan, leaves reach a peak in their capacity for photosynthesis,[39] and in tropical evergreen forests of some regions of the Amazon basin (particularly regions with long dry seasons), many trees produce more young leaves in the dry season,[40] seasonally increasing the photosynthetic capacity of the forest.[41]

Airborne sensors[]

Recent technological advances in studying the earth from space have resulted in a new field of phenological research that is concerned with observing the phenology of whole ecosystems and stands of vegetation on a global scale using proxy approaches. These methods complement the traditional phenological methods which recorded the first occurrences of individual species and phenophases.

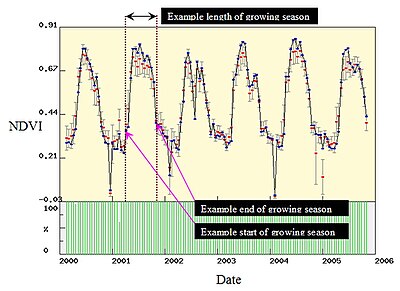

The most successful of these approaches is based on tracking the temporal change of a Vegetation Index (like Normalized Difference Vegetation Index(NDVI)). NDVI makes use of the vegetation's typical low reflection in the red (red energy is mostly absorbed by growing plants for Photosynthesis) and strong reflection in the Near Infrared (Infrared energy is mostly reflected by plants due to their cellular structure). Due to its robustness and simplicity, NDVI has become one of the most popular remote sensing based products. Typically, a vegetation index is constructed in such a way that the attenuated reflected sunlight energy (1% to 30% of incident sunlight) is amplified by ratio-ing red and NIR following this equation:

The evolution of the vegetation index through time, depicted by the graph above, exhibits a strong correlation with the typical green vegetation growth stages (emergence, vigor/growth, maturity, and harvest/senescence). These temporal curves are analyzed to extract useful parameters about the vegetation growing season (start of season, end of season, length of growing season, etc.). Other growing season parameters could potentially be extracted, and global maps of any of these growing season parameters could then be constructed and used in all sorts of climatic change studies.

A noteworthy example of the use of remote sensing based phenology is the work of Ranga Myneni[44] from Boston University. This work[45] showed an apparent increase in vegetation productivity that most likely resulted from the increase in temperature and lengthening of the growing season in the boreal forest.[46] Another example based on the MODIS enhanced vegetation index (EVI) reported by Alfredo Huete[47] at the University of Arizona and colleagues showed that the Amazon Rainforest, as opposed to the long-held view of a monotonous growing season or growth only during the wet rainy season, does in fact exhibit growth spurts during the dry season.[48][49]

However, these phenological parameters are only an approximation of the true biological growth stages. This is mainly due to the limitation of current space-based remote sensing, especially the spatial resolution, and the nature of vegetation index. A pixel in an image does not contain a pure target (like a tree, a shrub, etc.) but contains a mixture of whatever intersected the sensor's field of view.

Phenological mismatch[]

Most species, including both plants and animals, interact with one another within ecosystems and habitats, known as biological interactions.[50] These interactions (whether it be plant-plant, animal-animal, predator-prey or plant-animal interactions) can be vital to the success and survival of populations and therefore species.

Many species experience changes in life cycle development, migration or in some other process/behavior at different times in the season than previous patterns depict due to warming temperatures. Phenological mismatches, where interacting species change the timing of regularly repeated phases in their life cycles at different rates, creates a mismatch in interaction timing and therefore negatively harming the interaction.[51] Mismatches can occur in many different biological interactions, including between species in one trophic level (intratrophic interactions) (ie. plant-plant), between different trophic levels (intertrophic interactions) (ie. plant-animal) or through creating competition (intraguild interactions).[52] For example, if a plant species blooms its flowers earlier than previous years, but the pollinators that feed on and pollinate this flower does not arrive or grow earlier as well, then a phenological mismatch has occurred. This results in the plant population declining as there are no pollinators to aid in their reproductive success.[53] Another example includes the interaction between plant species, where the presence of one specie aids in the pollination of another through attraction of pollinators. However, if these plant species develop at mismatched times, this interaction will be negatively affected and therefore the plant species that relies on the other will be harmed.

Phenological mismatches means the loss of many biological interactions and therefore ecosystem functions are also at risk of being negatively effects or lost all together. Phenological mismatches his will effect species and ecosystems food webs, reproduction success, resource availability, population and community dynamics in future generations, and therefore evolutionary process and overall biodiversity.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Phenology". Merriam-Webster. 2020.

- ^

Meier, Nicole (2007). "Grape Harvest Records as a Proxy for Swiss April to August Temperature Reconstructions" (PDF). Diplomarbeit der Philosophisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bern (Thesis of Philosophy and Science Faculty of the University of Bern). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

Phenological grape harvest observations in Switzerland over the last 500 years have been used as a proxy indicator for reconstructing past temperature variability.

- ^ Meier, N.; Rutishauser, T.; Luterbacher, J.; Pfister, C.; Wanner, H. (2007). "Grape Harvest Dates as a proxy for Swiss April to August Temperature Reconstructions back to AD 1480". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (20): L20705. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3420705M. doi:10.1029/2007GL031381.

Phenological grape harvest observations in Switzerland over the last 500 years have been used as a proxy indicator for reconstructing past temperature variability.

- ^ Menzel, A.; Sparks, T.H.; Estrella, N.; Koch, E.; Aasa, A.; Ahas, R.; Alm-kübler, K.; Bissolli, P.; Braslavská, O.; Briede, A.; et al. (2006). "European phenological response to climate change matches the warming pattern". Global Change Biology. 12 (10): 1969–1976. Bibcode:2006GCBio..12.1969M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.167.960. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01193.x.

One of the preferred indicators is phenology, the science of natural recurring events, as their recorded dates provide a high-temporal resolution of ongoing changes.

- ^ Schwartz, M. D.; Ahas, R.; Aasa, A. (2006). "Onset of spring starting earlier across the Northern Hemisphere". Global Change Biology. 12 (2): 343–351. Bibcode:2006GCBio..12..343S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01097.x.

SI first leaf dates, measuring change in the start of ‘early spring’ (roughly the time of shrub budburst and lawn first greening), are getting earlier in nearly all parts of the Northern Hemisphere. The average rate of change over the 1955–2002 period is approximately -1.2 days per decade.

- ^ φαίνω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ λόγος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Demaree, G, and T Rutishauser. (2009). "Origins of the Word 'Phenology'". EOS. 90 (34): 291. Bibcode:2009EOSTr..90..291D. doi:10.1029/2009EO340004.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Demarée, Gaston R.; Chuine, Isabelle (2006). "A Concise History of Phenological Observations at the Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium" (PDF). In Dalezios, Nicolas R.; Tzortzios, Stergios (eds.). HAICTA International Conference on Information Systems in Sustainable Agriculture, Agro-environment and Food Technology (Volos, Greece); vol. 3. S.l.: University of Thessaly. pp. 815–824. OCLC 989158236. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ First published: Quetelet, Adolphe (1842). Observations des Phénomènes périodiques. Bruxelles: Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. OCLC 460607426; this publications was followed by yearly publications until 1864. See also: Demarée, Gaston R. (2009). "The Phenological Observations and Networking of Adolphe Quetelet at the Royal Observatory of Brussels" (PDF). Italian Journal of Agrometeorology. 14 (1). Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ Demarée & Rutishauser 2011, p. 756.

- ^ Demarée, Gaston R.; Rutishaler, This (2009). "Origins of the word 'Phenology'". EOS. 90 (34): 291. Bibcode:2009EOSTr..90..291D. doi:10.1029/2009EO340004.. See also [www.meteo.be/meteo/download/fr/4224538/pdf/rmi_scpub-1300.pdf for supplementary materials].

- ^ Morren 1849/1851, as cited in Demarée & Rutishauser 2011, p. 758.

- ^ Morren, Charles (1853). "Souvenirs phénologiques de l'hiver 1852-1853" ("Phenological memories of the winter 1852-1853")". Bulletin de l'Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique (in French). XX (1): 160-186. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ ’Ornithological meeting at Serajevo, Bosnia,’ in: The Zoologist,

4th series, vol 3 (1899), page 511.

4th series, vol 3 (1899), page 511.

- ^ Monahan, William B.; Rosemartin, Alyssa; Gerst, Katharine L.; Fisichelli, Nicholas A.; Ault, Toby; Schwartz, Mark D.; Gross, John E.; Weltzin, Jake F. (2016). "Climate change is advancing spring onset across the U.S. National park system". Ecosphere. 7 (10): e01465. doi:10.1002/ecs2.1465.

- ^ White, G (1789) The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne

- ^ Chuine, I.; Yiou, P.; Viovy, N.; Seguin, B.; Daux, V.; Le Roy, Ladurie (2004). "Grape ripening as a past climate indicator" (PDF). Nature. 432 (7015): 289–290. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..289C. doi:10.1038/432289a. PMID 15549085. S2CID 12339440. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28.

- ^ Keenan, D.J. (2007). "Grape harvest dates are poor indicators of summer warmth" (PDF). Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 87 (1–4): 255–256. Bibcode:2007ThApC..87..255K. doi:10.1007/s00704-006-0197-9. S2CID 120923572.

- ^ Sparks, T.H.; Carey, P.D. (1995). "The responses of species to climate over two centuries: an analysis of the Marsham phenological record, 1736-1947". Journal of Ecology. 83 (2): 321–329. doi:10.2307/2261570. JSTOR 2261570.

- ^ Jeffree, E.P. (1960). "Some long-term means from the Phenological reports (1891–1948) of the Royal Meteorological Society". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 86 (367): 95–103. Bibcode:1960QJRMS..86...95J. doi:10.1002/qj.49708636710.

- ^ Sparks T, Jeffree E, Jeffree C (2000). "An examination of the relationship between flowering times and temperature at the national scale using long-term phenological records from the UK". International Journal of Biometeorology. 44 (2): 82–87. Bibcode:2000IJBm...44...82S. doi:10.1007/s004840000049. PMID 10993562. S2CID 36711195.

- ^ SpringerLink - Abstract

- ^ Fitter A, Fitter R (2002). "Rapid changes in flowering time in British plants". Science. 296 (5573): 1689–1691. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1689F. doi:10.1126/science.1071617. PMID 12040195. S2CID 24973973.

- ^ Fitter, A. H.; Fitter, R. S. R. (31 May 2002). "Rapid Changes in Flowering Time in British Plants" (PDF). Science. 296 (5573): 1689–91. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1689F. doi:10.1126/science.1071617. PMID 12040195. S2CID 24973973. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Clover, Charles (27 August 2005). "Change in climate leads to a month more mowing". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ *Cramb, Auslan (3 September 2005). "Lawn diarist earns his stripes". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ *"David's lawn mower and global warming". Fife Today. 1 September 2005.

- ^ "A brief history of phenology - Nature's Calendar".

- ^ "A brief history of phenology - Nature's Calendar".

- ^ Burgess, Malcolm D.; Smith, Ken W.; Evans, Karl L.; Leech, Dave; Pearce-Higgins, James W.; Branston, Claire J.; Briggs, Kevin; Clark, John R.; du Feu, Chris R.; Lewthwaite, Kate; Nager, Ruedi G.; Sheldon, Ben C.; Smith, Jeremy A.; Whytock, Robin C.; Willis, Stephen G.; Phillimore, Albert B. (23 April 2018). "Tritrophic phenological match–mismatch in space and time" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (6): 970–975. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0543-1. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 29686235. S2CID 5040650.

- ^ Kaspar, Frank; Zimmermann, Kirsten; Polte-Rudolf, Christine (2014). "An overview of the phenological observation network and the phenological database of Germany's national meteorological service (Deutscher Wetterdienst)". Adv. Sci. Res. 11 (1): 93–99. Bibcode:2014AdSR...11...93K. doi:10.5194/asr-11-93-2014.

- ^ Templ, Barbara; Koch, Elisabeth; Bolmgren, K; Ungersböck, Markus; Paul, Anita; Scheifinger, H; Rutishauser, T; Busto, M; Chmielewski, FM; Hájková, L; Hodzić, S; Kaspar, Frank; Pietragalla, B; Romero-Fresneda, R; Tolvanen, A; Vučetič, V; Zimmermann, Kirsten; Zust, A (2018). "Pan European Phenological database (PEP725): a single point of access for European data". Int. J. Biometeorol. 62 (6): 1109–1113. Bibcode:2018IJBm...62.1109T. doi:10.1007/s00484-018-1512-8. PMID 29455297. S2CID 3379514.

- ^ Nature Saskatchewan : PlantWatch

- ^ "ClimateWatch". EarthWatch Institute Australia. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ BioWatch Home Archived July 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wu, Jin; Albert, Loren P.; Lopes, Aline P.; Restrepo-Coupe, Natalia; Hayek, Matthew; Wiedemann, Kenia T.; Guan, Kaiyu; Stark, Scott C.; Christoffersen, Bradley (2016-02-26). "Leaf development and demography explain photosynthetic seasonality in Amazon evergreen forests". Science. 351 (6276): 972–976. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..972W. doi:10.1126/science.aad5068. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26917771.

- ^ Restrepo-Coupe, Natalia; Da Rocha, Humberto R.; Hutyra, Lucy R.; Da Araujo, Alessandro C.; Borma, Laura S.; Christoffersen, Bradley; Cabral, Osvaldo M.R.; De Camargo, Plinio B.; Cardoso, Fernando L.; Da Costa, Antonio C. Lola; Fitzjarrald, David R.; Goulden, Michael L.; Kruijt, Bart; Maia, Jair M.F.; Malhi, Yadvinder S.; Manzi, Antonio O.; Miller, Scott D.; Nobre, Antonio D.; von Randow, Celso; Sá, Leonardo D. Abreu; Sakai, Ricardo K.; Tota, Julio; Wofsy, Steven C.; Zanchi, Fabricio B.; Saleska, Scott R. (2013-12-15). "What drives the seasonality of photosynthesis across the Amazon basin? A cross-site analysis of eddy flux tower measurements from the Brasil flux network" (PDF). Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 182–183: 128–144. Bibcode:2013AgFM..182..128R. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2013.04.031. ISSN 0168-1923.

- ^ Flexas, J.; Loreto; Medrano (2012). "Photosynthesis during leaf development and ageing". Terrestrial Photosynthesis in a Changing Environment: A Molecular, Physiological, and Ecological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 353–372. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139051477.028. ISBN 9781139051477.

- ^ Lopes, Aline Pontes; Nelson, Bruce Walker; Wu, Jin; Graça, Paulo Maurício Lima de Alencastro; Tavares, Julia Valentim; Prohaska, Neill; Martins, Giordane Augusto; Saleska, Scott R. (2016-09-01). "Leaf flush drives dry season green-up of the Central Amazon". Remote Sensing of Environment. 182: 90–98. Bibcode:2016RSEnv.182...90L. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2016.05.009. ISSN 0034-4257.

- ^ Albert, Loren P.; Wu, Jin; Prohaska, Neill; de Camargo, Plinio Barbosa; Huxman, Travis E.; Tribuzy, Edgard S.; Ivanov, Valeriy Y.; Oliveira, Rafael S.; Garcia, Sabrina (2018-03-04). "Age-dependent leaf physiology and consequences for crown-scale carbon uptake during the dry season in an Amazon evergreen forest". New Phytologist. 219 (3): 870–884. doi:10.1111/nph.15056. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 29502356. S2CID 3705589.

- ^ Tbrs, Modis Vi Cd-Rom Archived 2006-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 49971CU_Txt

- ^ Welcome to the Climate and Vegetation Research Group, Boston University

- ^ Myneni, RB; Keeling, CD; Tucker, CJ; Asrar, G; Nemani, RR (1997). "Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes from 1981 to 1991". Nature. 386 (6626): 698. Bibcode:1997Natur.386..698M. doi:10.1038/386698a0. S2CID 4235679.

- ^ ISI Web of Knowledge [v3.0]

- ^ Tbrs, Modis Vi Cd-Rom Archived 2006-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huete, Alfredo R.; Didan, Kamel; Shimabukuro, Yosio E.; Ratana, Piyachat; Saleska, Scott R.; Hutyra, Lucy R.; Yang, Wenze; Nemani, Ramakrishna R.; Myneni, Ranga (2006). "Amazon rainforests green-up with sunlight in dry season" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (6): L06405. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..33.6405H. doi:10.1029/2005GL025583. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Lindsey, Rebecca; Robert Simmon (June 30, 2006). "Defying Dry: Amazon Greener in Dry Season than Wet". The Earth Observatory. EOS Project Science Office, NASA Goddard. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ "Ecological Interactions". Khan Academy. 2020.

- ^ Renner, Susanne S.; Zohner, Constantin M. (2018-11-02). "Climate Change and Phenological Mismatch in Trophic Interactions Among Plants, Insects, and Vertebrates". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 49 (1): 165–182. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062535. ISSN 1543-592X.

- ^ Miller-Rushing, Abraham J.; Høye, Toke Thomas; Inouye, David W.; Post, Eric (2010-10-12). "The effects of phenological mismatches on demography". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1555): 3177–3186. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0148. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2981949. PMID 20819811.

- ^ Gonsamo, Alemu; Chen, Jing M.; Wu, Chaoyang (2013-07-19). "Citizen Science: linking the recent rapid advances of plant flowering in Canada with climate variability". Scientific Reports. 3 (1): 2239. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E2239G. doi:10.1038/srep02239. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3715764. PMID 23867863.

Sources[]

- Demarée, Gaston R; Rutishauser, This (2011). "From "Periodical Observations" to "Anthochronology" and "Phenology" – the scientific debate between Adolphe Quetelet and Charles Morren on the origin of the word "Phenology"" (PDF). International Journal of Biometeorology. 55 (6): 753–761. Bibcode:2011IJBm...55..753D. doi:10.1007/s00484-011-0442-5. PMID 21713602. S2CID 1486224.

External links[]

- North American Bird Phenology Program Citizen science program to digitize bird phenology records

- Project Budburst Citizen Science for Plant Phenology in the USA

- USA National Phenology Network Citizen science and research network observations on phenology in the USA

- AMC's Mountain Watch Citizen science and phenology monitoring in the Appalachian mountains

- Pan European Phenology Project PEP725 European open access database with plant phenology data sets for science, research and education

- UK Nature's Calendar UK Phenology network

- DWD phenology website Information on the plant phenological network operated by Germany's national meteorological service (DWD)

- Nature's Calendar Ireland Spring Watch & Autumn Watch

- Naturewatch: A Canadian Phenology project

- Spring Alive Project Phenological survey on birds for children

- Moj Popek Citizen Science for Plant Phenology in Slovenia

- Observatoire des Saisons French Phenology network

- Phenology Video produced by Wisconsin Public Television

- Austrian phenological network run by ZAMG

- Periodic phenomena

- Chronobiology

- Ecology

- Climatology

- Branches of biology