Piano Concerto No. 3 (Rachmaninoff)

Sergei Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30, was composed in the summer of 1909. The piece was premiered on November 28 of that year in New York City with the composer as soloist, accompanied by the New York Symphony Society under Walter Damrosch. The work often has the reputation of being one of the most technically challenging piano concertos in the standard classical piano repertoire.

History[]

Rachmaninoff composed the concerto in Dresden[1] completing it on September 23, 1909. Contemporary with this work are his First Piano Sonata and his tone poem The Isle of the Dead.

Owing to its difficulty, the concerto is respected, even feared, by many pianists. Josef Hofmann, the pianist to whom the work is dedicated, never publicly performed it, saying that it "wasn't for" him. Gary Graffman lamented he had not learned this concerto as a student, when he was "still too young to know fear".[2]

Due to time constraints, Rachmaninoff could not practice the piece while in Russia. Instead, he practiced it on a silent keyboard that he brought with him while en route to the United States. The concerto was first performed on Sunday, November 28, 1909 at the New Theatre in New York City. Rachmaninoff was the soloist, with the New York Symphony Society with Walter Damrosch conducting. The work received a second performance under Gustav Mahler on January 16, 1910, an "experience Rachmaninoff treasured."[3] Rachmaninoff later described the rehearsal to Riesemann:

At that time Mahler was the only conductor whom I considered worthy to be classed with Nikisch. He devoted himself to the concerto until the accompaniment, which is rather complicated, had been practiced to perfection, although he had already gone through another long rehearsal. According to Mahler, every detail of the score was important – an attitude too rare amongst conductors. ... Though the rehearsal was scheduled to end at 12:30, we played and played, far beyond this hour, and when Mahler announced that the first movement would be rehearsed again, I expected some protest or scene from the musicians, but I did not notice a single sign of annoyance. The orchestra played the first movement with a keen or perhaps even closer appreciation than the previous time.[4]

The score was first published in 1910 by Gutheil. Rachmaninoff called the Third the favorite of his own piano concertos, stating that "I much prefer the Third, because my Second is so uncomfortable to play." Nevertheless, it was not until the 1930s and largely thanks to the advocacy of Vladimir Horowitz that the Third concerto became popular.

Instrumentation[]

The concerto is scored for solo piano and an orchestra consisting of 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in B-flat, 2 bassoons, 4 horns in F, 2 trumpets in B-flat, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, and strings.

Structure[]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by Vladimir Ashkenazy with the London Symphony Orchestra, André Previn conducting | |

The work follows the form of a standard piano concerto, constructed into three movements. The end of the second movement leads directly into the third without interruption.

- Allegro ma non tanto (D minor)

- The first movement is in sonata-allegro form. The piece revolves around a diatonic melody which Rachmaninoff claimed "wrote itself".[5] The theme soon develops into complex and busy pianistic figuration.

- The second theme opens with quiet exchanges between the orchestra and the piano before fully diving into the second theme in B♭ major. The first part of the first theme is restated before the movement is pulled into a loud development section in C minor which opens with toccata-like quavers in the piano and reaches a loud chordal section. The whole development exhibits features similar to a canon, such as an eighth note passage in the piano in which the left hand and the right hand play overlapping figures. The movement reaches a number of ferocious climaxes, especially in the cadenza.

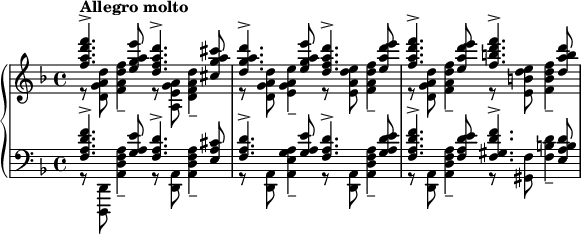

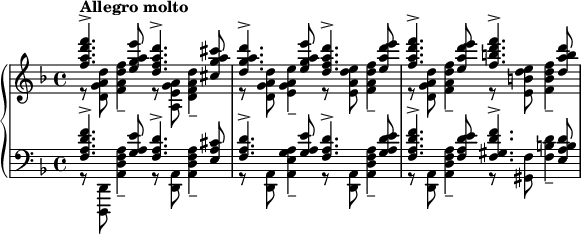

Portion of the original cadenza (ossia)

Portion of the original cadenza (ossia)- Rachmaninoff wrote two versions of this cadenza: the chordal original, which is commonly notated as the ossia, and a second one with a lighter, toccata-like style. Both cadenzas lead into a quiet solo section where the flute, oboe, clarinet and horn individually restate the first theme of the exposition, accompanied by delicate arpeggios in the piano. The cadenza then ends quietly, but the piano alone continues to play a quiet development of the exposition's second theme in E♭ major before leading to the recapitulation, where the first theme is restated by the piano, with the orchestra accompanying, soon closing with a quiet, rippling coda reminiscent of the second theme.

- Intermezzo: Adagio (D minor → F♯ minor → D♭ major → B♭ minor → F♯ minor → D minor)

- The second movement is constructed around a theme and variations, in an ABACA form, while shifting around various home keys. The theme and first two variations are played by the orchestra alone. The piano then plays several variations with and without the orchestra.

- After the first theme development and recapitulation of the second theme, the main melody from the first movement reappears, before the movement is closed by the orchestra in a manner similar to the introduction. The piano ends the movement with a short, violent "cadenza-esque" passage which moves into the last movement without pause. Many melodic thoughts of this movement allude to Rachmaninoff's second piano concerto, third movement, noticeably the Russian-like E♭ major melody.

- Finale: Alla breve (D minor → E♭ Major → D minor → D major)

- The third movement is in a modified sonata-allegro form, and is quick and vigorous.

- The movement contains variations on many of the themes that are used in the first movement, which unites the concerto cyclically. However, after the first and second themes it diverges from the regular sonata-allegro form. There is no conventional development; that segment is replaced by a lengthy digression in E♭ major, which leads to the two themes from the first movement. After the digression, the movement recapitulation returns to the original themes, building up to a toccata climax somewhat similar but lighter than the first movement's ossia cadenza and accompanied by the orchestra. The movement concludes with a triumphant and passionate second theme melody in D major. The piece ends with the same four-note rhythm – claimed by some to be the composer's musical signature – as it is used in both the composer's second concerto and second symphony.

Rachmaninoff, under pressure, and hoping to make his work more popular, authorized several cuts in the score, to be made at the performer's discretion. These cuts, particularly in the second and third movements, were commonly taken in performance and recordings during the initial decades following the concerto's publication. More recently, it has become commonplace to perform the concerto without cuts. A typical performance of the complete concerto has a duration of about forty minutes.

In popular culture[]

The concerto is significant in the 1996 film Shine, based on the life of pianist David Helfgott.

References[]

- ^ Leonard, Richard Anthony (1956). A History of Russian Music. London: Jarrold's Publishers. p. 236.

- ^ David Dubal, The Art of the Piano, third edition (2004), Amadeus Press

- ^ "Program Notes: Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3". Archived from the original on 2005-04-20. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- ^ recounted in Sergei Rachmaninoff: A Lifetime in Music, p. 164, Sergei Bertensson, Jay Leyda, and Sophia Satina, Indiana University Press, 1956

- ^ Cobb, Gary. "a Descriptive Analysis of the Piano Concertos of Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

Further reading[]

- Anderson, W[ill] R. (1946). Rachmaninov and His Pianoforte Concertos. A brief sketch of the composer and his style. London: Hinrichsen. OCLC 1268692. OL 22358215M.

- Yasser, Joseph (July 1969). "The Opening Theme of Rachmaninoff's Third Piano Concerto and its Liturgical Prototype". The Musical Quarterly. 55 (3): 313–328. doi:10.1093/mq/LV.3.313. JSTOR 741003.

External links[]

- Piano Concerto No. 3: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Rachmaninoff's Works for Piano and Orchestra An analysis of Rachmaninoff's Works for Piano and Orchestra including the Piano Concertos and the Paganini Rhapsody

- Piano concertos by Sergei Rachmaninoff

- 1909 compositions

- Compositions in D minor

- Music with dedications