Politics of the United States

Politics of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polity type | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| Constitution | United States Constitution |

| Formation | March 4, 1789 |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Congress |

| Type | Bicameral |

| Meeting place | Capitol |

| Upper house | |

| Name | Senate |

| Presiding officer | Kamala Harris, Vice President & President of the Senate |

| Appointer | Direct Election |

| Lower house | |

| Name | House of Representatives |

| Presiding officer | Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the House of Representatives |

| Appointer | Exhaustive ballot |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State and Government | |

| Title | President |

| Currently | Joe Biden |

| Appointer | Electoral College |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of the United States |

| Current cabinet | Cabinet of Joe Biden |

| Leader | President |

| Deputy leader | Vice President |

| Appointer | President |

| Headquarters | White House |

| Ministries | 15 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Federal judiciary of the United States |

| Courts | Courts of the United States |

| Supreme Court | |

| Chief judge | John Roberts |

| Seat | Supreme Court Building |

|

|---|

|

The United States is a democratic constitutional federal republic, in which the president (the head of state and head of government), Congress, and judiciary share powers reserved to the national government, and the federal government shares sovereignty with the state governments.

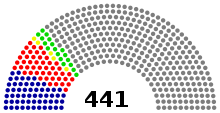

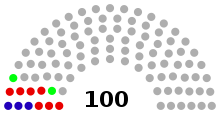

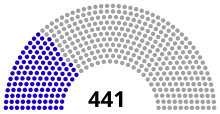

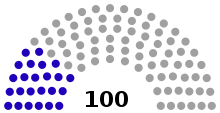

The executive branch is headed by the president and is independent of the legislature. Legislative power is vested in the two chambers of Congress: the Senate and the House of Representatives. The judicial branch (or judiciary), composed of the Supreme Court and lower federal courts, exercises judicial power. The judiciary's function is to interpret the United States Constitution and federal laws and regulations. This includes resolving disputes between the executive and legislative branches. The federal government's layout is explained in the Constitution. Two political parties, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, have dominated American politics since the American Civil War, although other parties have also existed.

There are major differences between the political system of the United States and that of most other developed capitalist countries. These include increased power of the upper house of the legislature, a wider scope of power held by the Supreme Court, the separation of powers between the legislature and the executive, and the dominance of only two main parties. The United States is one of the world's developed democracies where third parties have the least political influence. Furthermore, concerns have been raised over the level of political influence held by different demographic groups. For women and minority demographics, in particular, a lack of proportionate representation and political influence have been connected to broader concerns about democracy in the United States.

The federal entity created by the U.S. Constitution is the dominant feature of the American governmental system. However, most residents are also subject to a state government, and also subject to various units of local government. The latter includes counties, municipalities, and special districts.

State government[]

State governments have the power to make laws on all subjects that are not granted to the federal government nor denied to the states in the U.S. Constitution. These include education, family law, contract law, and most crimes. Unlike the federal government, which only has those powers granted to it in the Constitution, a state government has inherent powers allowing it to act unless limited by a provision of the state or national constitution.

Like the federal government, state governments have three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The chief executive of a state is its popularly elected governor, who typically holds office for a four-year term (although in some states the term is two years). Except for Nebraska, which has unicameral legislature, all states have a bicameral legislature, with the upper house usually called the Senate and the lower house called the House of Representatives, the Assembly or something similar. In most states, senators serve four-year terms, and members of the lower house serve two-year terms.

The constitutions of the various states differ in some details but generally follow a pattern similar to that of the federal Constitution, including a statement of the rights of the people and a plan for organizing the government. However, state constitutions are generally more detailed.

At the state and local level, the process of initiatives and referendums allow citizens to place new legislation on a popular ballot, or to place legislation that has recently been passed by a legislature on a ballot for a popular vote. Initiatives and referendums, along with recall elections and popular primary elections, are signature reforms of the Progressive Era; they are written into several state constitutions, particularly in the Western states.

Local government[]

There are 89,500 local governments, including 3,033 counties, 19,492 municipalities, 16,500 townships, 13,000 school districts, and 37,000 other special districts.[1] Local governments directly serve the needs of the people, providing everything from police and fire protection to sanitary codes, health regulations, education, public transportation, and housing. Typically local elections are nonpartisan - local activists suspend their party affiliations when campaigning and governing.[2]

About 28% of the people live in cities of 100,000 or more population. City governments are chartered by states, and their charters detail the objectives and powers of the municipal government. For most big cities, cooperation with both state and federal organizations is essential to meeting the needs of their residents. Types of city governments vary widely across the nation. However, almost all have a central council, elected by the voters, and an executive officer, assisted by various department heads, to manage the city's affairs. Cities in the West and South usually have nonpartisan local politics.

There are three general types of city government: the mayor-council, the commission, and the council-manager. These are the pure forms; many cities have developed a combination of two or three of them.

Mayor-Council[]

This is the oldest form of city government in the United States and, until the beginning of the 20th century, was used by nearly all American cities. Its structure is like that of the state and national governments, with an elected mayor as chief of the executive branch and an elected council that represents the various neighborhoods forming the legislative branch. The mayor appoints heads of city departments and other officials (sometimes with the approval of the council), has the power of veto over ordinances (the laws of the city), and often is responsible for preparing the city's budget. The council passes city ordinances, sets the tax rate on property, and apportions money among the various city departments. As cities have grown, council seats have usually come to represent more than a single neighborhood.

Commission[]

This combines both the legislative and executive functions in one group of officials, usually three or more in number, elected city-wide. Each commissioner supervises the work of one or more city departments. Commissioners also set policies and rules by which the city is operated. One is named chairperson of the body and is often called the mayor, although their power is equivalent to that of the other commissioners.[3]

Council-Manager[]

The city manager is a response to the increasing complexity of urban problems that need management ability not often possessed by elected public officials. The answer has been to entrust most of the executive powers, including law enforcement and provision of services, to a highly trained and experienced professional city manager.

The council-manager plan has been adopted by a large number of cities. Under this plan, a small, elected council makes the city ordinances and sets policy, but hires a paid administrator, also called a city manager, to carry out its decisions. The manager draws up the city budget and supervises most of the departments. Usually, there is no set term; the manager serves as long as the council is satisfied with their work.

County government[]

The county is a subdivision of the state, sometimes (but not always) containing two or more townships and several villages. New York City is so large that it is divided into five separate boroughs, each a county in its own right. On the other hand, Arlington County, Virginia, the United States' smallest county, located just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., is both an urbanized and suburban area, governed by a unitary county administration. In other cities, both the city and county governments have merged, creating a consolidated city–county government.

In most U.S. counties, one town or city is designated as the county seat, and this is where the government offices are located and where the board of commissioners or supervisors meets. In small counties, boards are chosen by the county; in the larger ones, supervisors represent separate districts or townships. The board collects taxes for state and local governments; borrows and appropriates money; fixes the salaries of county employees; supervises elections; builds and maintains highways and bridges; and administers national, state, and county welfare programs. In very small counties, the executive and legislative power may lie entirely with a sole commissioner, who is assisted by boards to supervise taxes and elections. In some New England states, counties do not have any governmental function and are simply a division of land.

Town and village government[]

Thousands of municipal jurisdictions are too small to qualify as city governments. These are chartered as towns and villages and deal with local needs such as paving and lighting the streets, ensuring a water supply, providing police and fire protection, and waste management. In many states of the US, the term town does not have any specific meaning; it is simply an informal term applied to populated places (both incorporated and unincorporated municipalities). Moreover, in some states, the term town is equivalent to how civil townships are used in other states.

The government is usually entrusted to an elected board or council, which may be known by a variety of names: town or village council, board of selectmen, board of supervisors, board of commissioners. The board may have a chairperson or president who functions as chief executive officer, or there may be an elected mayor. Governmental employees may include clerk, treasurer, police, fire officers and health and welfare officers.

One unique aspect of local government, found mostly in the New England region of the United States, is the town meeting. Once a year, sometimes more often if needed, the registered voters of the town meet in open session to elect officers, debate local issues, and pass laws for operating the government. As a body, they decide on road construction and repair, construction of public buildings and facilities, tax rates, and the town budget. The town meeting, which has existed for more than three centuries in some places, is often cited as the purest form of direct democracy, in which the governmental power is not delegated, but is exercised directly and regularly by all the people.

Suffrage[]

Suffrage is nearly universal for citizens 18 years of age and older. All states and the District of Columbia contribute to the electoral vote for president. However, the District, and other U.S. holdings like Puerto Rico and Guam, lack representation in Congress. These constituencies do not have the right to choose any political figure outside their respective areas. Each commonwealth, territory, or district can only elect a non-voting delegate to serve in the House of Representatives.

Voting rights are sometimes restricted as a result of felony conviction, but such laws vary widely by state. Election of the president is an indirect suffrage: voters vote for electors who comprise the United States Electoral College and who, in turn vote for president.[4] These presidential electors were originally expected to exercise their own judgement. In modern practice, though, they are expected to vote as pledged and some faithless electors have not.

Unincorporated areas[]

Some states contain unincorporated areas, which are areas of land not governed by any local authorities and rather just by the county, state and federal governments. Residents of unincorporated areas only need to pay taxes to the county, state and federal governments as opposed to the municipal government as well. A notable example of this is Paradise, Nevada, an unincorporated area where many of the casinos commonly associated with Las Vegas are situated.[5]

Unincorporated territories[]

The United States possesses a number of unincorporated territories, including 16 island territories across the globe.[6] These are areas of land which are not under the jurisdiction of any state, and do not have a government established by Congress through an organic act. Citizens of these territories can vote for members of their own local governments, and some can also elect representatives to serve in Congress—though they only have observer status.[6] The unincorporated territories of the U.S. include American Samoa, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, Wake Island, and others. American Samoa is the only territory with a native resident population and is governed by a local authority. Despite the fact that an organic act was not passed in Congress, American Samoa established its own constitution in 1967, and has self governed ever since.[7] Seeking statehood or independence is often debated in US territories, such as in Puerto Rico, but even if referendums on these issues are held, congressional approval is needed for changes in status to take place.[8]

The citizenship status of residents in US unincorporated territories has caused concern for their ability to influence and participate in the politics of the United States. In recent decades, the Supreme Court has established voting as a fundamental right of US citizens, even though residents of territories do not hold full voting rights.[9] Despite this, residents must still abide by federal laws that they cannot equitably influence, as well as register for the national Selective Service System, which has led some scholars to argue that residents of territories are essentially second-class citizens.[9] The legal justifications for these discrepancies stem from the Insular Cases, which were a series of 1901 Supreme Court cases that some consider to be reflective of imperialism and racist views held in the United States.[6] Unequal access to political participation in US territories has also been criticized for affecting US citizens who move to territories, as such an action requires forfeiting the full voting rights that they would have held in the 50 states.[9]

Campaign finance[]

Successful participation, especially in federal elections, requires large amounts of money, especially for television advertising.[10] This money is very difficult to raise by appeals to a mass base,[11] although in the 2008 election, candidates from both parties had success with raising money from citizens over the Internet.,[12] as had Howard Dean with his Internet appeals. Both parties generally depend on wealthy donors and organizations - traditionally the Democrats depended on donations from organized labor while the Republicans relied on business donations[citation needed]. Since 1984, however, the Democrats' business donations have surpassed those from labor organizations[citation needed]. This dependency on donors is controversial, and has led to laws limiting spending on political campaigns being enacted (see campaign finance reform). Opponents of campaign finance laws cite the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech, and challenge campaign finance laws because they attempt to circumvent the people's constitutionally guaranteed rights. Even when laws are upheld, the complication of compliance with the First Amendment requires careful and cautious drafting of legislation, leading to laws that are still fairly limited in scope, especially in comparison to those of other countries such as the United Kingdom, France or Canada.

Political culture[]

Colonial origins[]

The American political culture is deeply rooted in the colonial experience and the American Revolution. The colonies were unique within the European world for their vibrant political culture, which attracted ambitious young men into politics.[13] At the time, American suffrage was the most widespread in the world, with every man who owned a certain amount of property allowed to vote. Despite the fact that fewer than 1% of British men could vote, most white American men were eligible. While the roots of democracy were apparent, deference was typically shown to social elites in colonial elections, although this declined sharply with the American Revolution.[14] In each colony a wide range of public and private business was decided by elected bodies, especially the assemblies and county governments.[15] Topics of public concern and debate included land grants, commercial subsidies, and taxation, as well as the oversight of roads, poor relief, taverns, and schools. Americans spent a great deal of time in court, as private lawsuits were very common. Legal affairs were overseen by local judges and juries, with a central role for trained lawyers. This promoted the rapid expansion of the legal profession, and dominant role of lawyers in politics was apparent by the 1770s, with notable individuals including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, among many others.[16] The American colonies were unique in world context because of the growth of representation of different interest groups. Unlike Europe, where the royal court, aristocratic families and the established church were in control, the American political culture was open to merchants, landlords, petty farmers, artisans, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Quakers, Germans, Scotch Irish, Yankees, Yorkers, and many other identifiable groups. Over 90% of the representatives elected to the legislature lived in their districts, unlike England where it was common to have a member of Parliament and absentee member of Parliament. Finally, and most dramatically, the Americans were fascinated by and increasingly adopted the political values of Republicanism, which stressed equal rights, the need for virtuous citizens, and the evils of corruption, luxury, and aristocracy.[17] None of the colonies had political parties of the sort that formed in the 1790s, but each had shifting factions that vied for power.

American ideology[]

Republicanism, along with a form of classical liberalism remains the dominant ideology. Central documents include the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Constitution (1787), the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (1787-1790s), the Bill of Rights (1791), and Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address" (1863), among others. Among the core tenets of this ideology are the following:

- Civic duty: citizens have the responsibility to understand and support the government, participate in elections, pay taxes, and perform military service.

- Opposition to Political corruption.

- Democracy: The government is answerable to citizens, who may change the representatives through elections.

- Equality before the law: The laws should attach no special privilege to any citizen. Government officials are subject to the law just as others are.

- Freedom of religion: The government can neither support nor suppress any or all religion.

- Freedom of speech: The government cannot restrict through law or action the personal, non-violent speech of a citizen; a marketplace of ideas.

At the time of the United States' founding, the economy was predominantly one of agriculture and small private businesses, and state governments left welfare issues to private or local initiative. As in the UK and other industrialized countries, laissez-faire ideology was largely discredited during the Great Depression. Between the 1930s and 1970s, fiscal policy was characterized by the Keynesian consensus, a time during which modern American liberalism dominated economic policy virtually unchallenged.[18][19] Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, laissez-faire ideology has once more become a powerful force in American politics.[20] While the American welfare state expanded more than threefold after WWII, it has been at 20% of GDP since the late 1970s.[21][22] Today, modern American liberalism, and modern American conservatism are engaged in a continuous political battle, characterized by what the Economist describes as "greater divisiveness [and] close, but bitterly fought elections."[23]

Before World War II, the United States pursued a noninterventionist policy of in foreign affairs by not taking sides in conflicts between foreign powers. The country abandoned this policy when it became a superpower, and the country mostly supports internationalism.

Researchers have looked at authoritarian values. The main argument of this paper is that long-run economic changes from globalization have a negative impact on the social identity of historically dominant groups. This leads to an increase in authoritarian values because of an increased incentive to force minority groups to conform to social norms.[24]

Political parties and elections[]

The United States Constitution has never formally addressed the issue of political parties, primarily because the Founding Fathers did not originally intend for American politics to be partisan. In Federalist Papers No. 9 and No. 10, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, respectively, wrote specifically about the dangers of domestic political factions. In addition, the first president of the United States, George Washington, was not a member of any political party at the time of his election or throughout his tenure as president, and remains to this day the only independent to have held the office. Furthermore, he hoped that political parties would not be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation.[25] Nevertheless, the beginnings of the American two-party system emerged from his immediate circle of advisers, including Hamilton and Madison.

In partisan elections, candidates are nominated by a political party or seek public office as an independent. Each state has significant discretion in deciding how candidates are nominated, and thus eligible to appear on the election ballot. Typically, major party candidates are formally chosen in a party primary or convention, whereas minor party and Independents are required to complete a petitioning process.

Political parties[]

| American voter registration statistics as of October 2020[26] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Registered voters | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 48,517,845 | 39.58 | |

| Republican | 36,132,743 | 29.48 | |

| No party preference | 34,798,906 | 28.39 | |

| Other | 3,127,800 | 2.55 | |

| Totals | 122,577,294 | 100.00 | |

The modern political party system in the United States is a two-party system dominated by the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. These two parties have won every United States presidential election since 1852 and have controlled the United States Congress since at least 1856. From time to time, several other third parties have achieved relatively minor representation at the national and state levels.

Among the two major parties, the Democratic Party generally positions itself as center-left in American politics and supports an American liberalism platform, while the Republican Party generally positions itself as center-right and supports an American conservatism platform.

Elections[]

As in the United Kingdom and in other similar parliamentary systems, in the U.S. eligible Americans vote for a specific candidate. With a federal government, officials are elected at the federal (national), state and local levels. On a national level, the president is elected indirectly by the people, but instead elected through the Electoral College. In modern times, the electors almost always vote with the popular vote of their state, however in rare occurrences they may vote against the popular vote of their state, becoming what is known as a faithless elector. All members of Congress, and the offices at the state and local levels are directly elected.

Both federal and state laws regulate elections. The United States Constitution defines (to a basic extent) how federal elections are held, in Article One and Article Two and various amendments. State law regulates most aspects of electoral law, including primaries, the eligibility of voters (beyond the basic constitutional definition), the running of each state's electoral college, and the running of state and local elections.

Gerrymandering[]

Gerrymandering is a process frequently used to adjust the boundaries of electoral districts in order to advantage one political party over the other, representing a confluence of elections and political parties. In addition to primarily favoring the voters of only one party, gerrymandering has also been criticized for its impact on minority voters in the United States. Minority voters are often concentrated into single districts which can reduce their potential to otherwise influence elections in other districts—though this process can also help ensure the election of a representative of the same race.[27] However, some racial groups, such as Asian Americans, that do not form a majority in a district's population can miss out on this potential benefit.[28] Similarly, women are rarely concentrated in a way where they compose a significant majority of district's population, meaning that gerrymandering does not provide any counter-benefits to the dilution of the value of their votes.[28]

While gerrymandering can cause people to doubt the value of their votes in certain elections, the process has provided some benefits to minorities and marginalized groups. The majority of studies on descriptive representation have suggested that districts where at least 50% of the voter base is composed of minority voters have a higher likelihood of minority representation.[29] Additionally, the minority representatives elected from these districts are frequently reelected, which can increase their ability to gain seniority in a legislature or their party.[27]

Organization of American political parties[]

American political parties are more loosely organized than those in other countries. The two major parties, in particular, have no formal organization at the national level that controls membership. Thus, for an American to say that they are a member of the Democratic or Republican parties is quite different from a Briton's stating that they are a member of the Conservative or Labour parties. In most U.S. states, a voter can register as a member of one or another party and/or vote in the primary election for one or another party. A person may choose to attend meetings of one local party committee one day and another party committee the next day.

Party identification becomes somewhat formalized when a person runs for partisan office. In most states, this means declaring oneself a candidate for the nomination of a particular party and intent to enter that party's primary election for an office. A party committee may choose to endorse one or another of those who is seeking the nomination, but in the end the choice is up to those who choose to vote in the primary, and it is often difficult to tell who is going to do the voting.

The result is that American political parties have weak central organizations and little central ideology, except by consensus. A party really cannot prevent a person who disagrees with the majority of positions of the party or actively works against the party's aims from claiming party membership, so long as the voters who choose to vote in the primary elections elect that person. Once in office, an elected official may change parties simply by declaring such intent.

At the federal level, each of the two major parties has a national committee (See, Democratic National Committee, Republican National Committee) that acts as the hub for much fund-raising and campaign activities, particularly in presidential campaigns. The exact composition of these committees is different for each party, but they are made up primarily of representatives from state parties and affiliated organizations, and others important to the party. However, the national committees do not have the power to direct the activities of members of the party.

Both parties also have separate campaign committees which work to elect candidates at a specific level. The most significant of these are the Hill committees, which work to elect candidates to each house of Congress.

State parties exist in all fifty states, though their structures differ according to state law, as well as party rules at both the national and the state level.

Despite these weak organizations, elections are still usually portrayed as national races between the political parties. In what is known as "presidential coattails", candidates in presidential elections become the de facto leader of their respective party, and thus usually bring out supporters who in turn then vote for his party's candidates for other offices. On the other hand, federal midterm elections (where only Congress and not the president is up for election) are usually regarded as a referendum on the sitting president's performance, with voters either voting in or out the president's party's candidates, which in turn helps the next session of Congress to either pass or block the president's agenda, respectively.[30][31]

Political pressure groups[]

Special interest groups advocate the cause of their specific constituency. Business organizations will favor low corporate taxes and restrictions of the right to strike, whereas labor unions will support minimum wage legislation and protection for collective bargaining. Other private interest groups, such as churches and ethnic groups, are more concerned about broader issues of policy that can affect their organizations or their beliefs.

One type of private interest group that has grown in number and influence in recent years is the political action committee or PAC. These are independent groups, organized around a single issue or set of issues, which contribute money to political campaigns for United States Congress or the presidency. PACs are limited in the amounts they can contribute directly to candidates in federal elections. There are no restrictions, however, on the amounts PACs can spend independently to advocate a point of view or to urge the election of candidates to office. PACs today number in the thousands.[citation needed]

"The number of interest groups has mushroomed, with more and more of them operating offices in Washington, D.C., and representing themselves directly to Congress and federal agencies," says Michael Schudson in his 1998 book The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life. "Many organizations that keep an eye on Washington seek financial and moral support from ordinary citizens. Since many of them focus on a narrow set of concerns or even on a single issue, and often a single issue of enormous emotional weight, they compete with the parties for citizens' dollars, time, and passion."

The amount of money spent by these special interests continues to grow, as campaigns become increasingly expensive. Many Americans have the feeling that these wealthy interests, whether corporations, unions or PACs, are so powerful that ordinary citizens can do little to counteract their influences.

A survey of members of the American Economic Association find the vast majority regardless of political affiliation to be discontent with the current state of democracy in America. The primary concern relates to the prevalence and influence of special interest groups within the political process, which tends to lead to policy consequences that only benefit such special interest groups and politicians. Some conjecture that maintenance of the policy status quo and hesitance to stray from it perpetuates a political environment that fails to advance society's welfare.[32]

General developments[]

Many of America's Founding Fathers hated the thought of political parties.[33] They were sure quarreling factions would be more interested in contending with each other than in working for the common good. They wanted citizens to vote for candidates without the interference of organized groups, but this was not to be.

By the 1790s, different views of the new country's proper course had already developed, and those who held these opposing views tried to win support for their cause by banding together. The followers of Alexander Hamilton, the Hamiltonian faction, took up the name "Federalist"; they favored a strong central government that would support the interests of commerce and industry. The followers of Thomas Jefferson, the Jeffersonians and then the "Anti-Federalists," took up the name "Democratic-Republicans"; they preferred a decentralized agrarian republic in which the federal government had limited power. By 1828, the Federalists had disappeared as an organization, replaced by the Whigs, brought to life in opposition to the election that year of President Andrew Jackson. Jackson's presidency split the Democratic-Republican Party: Jacksonians became the Democratic Party and those following the leadership of John Quincy Adams became the "National Republicans." The two-party system, still in existence today, was born. (Note: The National Republicans of John Quincy Adams is not the same party as today's Republican Party.)

In the 1850s, the issue of slavery took center stage, with disagreement in particular over the question of whether slavery should be permitted in the country's new territories in the West. The Whig Party straddled the issue and sank to its death after the overwhelming electoral defeat by Franklin Pierce in the 1852 presidential election. Ex-Whigs joined the Know Nothings or the newly formed Republican Party. While the Know Nothing party was short-lived, Republicans would survive the intense politics leading up to the Civil War. The primary Republican policy was that slavery be excluded from all the territories. Just six years later, this new party captured the presidency when Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860. By then, parties were well established as the country's dominant political organizations, and party allegiance had become an important part of most people's consciousness. Party loyalty was passed from fathers to sons, and party activities, including spectacular campaign events, complete with uniformed marching groups and torchlight parades, were a part of the social life of many communities.

By the 1920s, however, this boisterous folksiness had diminished. Municipal reforms, civil service reform, corrupt practices acts, and presidential primaries to replace the power of politicians at national conventions had all helped to clean up politics.[34]

Development of the two-party system in the United States[]

Since the 1790s, the country has been run by two major parties. They try to defeat the other party, but not to destroy it.[35]

Occasional minor (or "third") political parties appear from time to time; they seldom last more than a decade. At various times the Socialist Party, the Farmer-Labor Party and the Populist Party for a few years had considerable local strength, and then faded away. A few merged into the mainstream. For example, in Minnesota, the Farmer–Labor Party merged into the state's Democratic Party, which is now officially known as the Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party. At present, the small Libertarian Party has lasted for years and is usually the largest in national elections, but rarely elects anyone. New York State has a number of additional third parties, who sometimes run their own candidates for office and sometimes nominate the nominees of the two main parties. In the District of Columbia, the D.C. Statehood Party has served as a third party with one issue.[36]

Almost all public officials in America are elected from single-member districts and win office by beating out their opponents in a system for determining winners called first-past-the-post; the one who gets the plurality wins, (which is not the same thing as actually getting a majority of votes). This encourages the two-party system; see Duverger's law. In the absence of multi-seat congressional districts, proportional representation is impossible and third parties cannot thrive. Senators were originally selected by state legislatures, but have been elected by popular vote since 1913. Although elections to the Senate elect two senators per constituency (state), staggered terms effectively result in single-seat constituencies for elections to the Senate.

Another critical factor has been ballot access law. Originally, voters went to the polls and publicly stated which candidate they supported. Later on, this developed into a process whereby each political party would create its own ballot and thus the voter would put the party's ballot into the voting box. In the late nineteenth century, states began to adopt the Australian Secret Ballot Method, and it eventually became the national standard. The secret ballot method ensured that the privacy of voters would be protected (hence government jobs could no longer be awarded to loyal voters) and each state would be responsible for creating one official ballot. The fact that state legislatures were dominated by Democrats and Republicans provided these parties an opportunity to pass discriminatory laws against minor political parties, yet such laws did not start to arise until the first Red Scare that hit America after World War I. State legislatures began to enact tough laws that made it harder for minor political parties to run candidates for office by requiring a high number of petition signatures from citizens and decreasing the length of time that such a petition could legally be circulated.

Although party members will usually "toe the line" and support their party's policies, they are free to vote against their own party and vote with the opposition ("cross the aisle") when they please.

"In America the same political labels (Democratic and Republican) cover virtually all public officeholders, and therefore most voters are everywhere mobilized in the name of these two parties," says Nelson W. Polsby, professor of political science, in the book New Federalist Papers: Essays in Defense of the Constitution. "Yet Democrats and Republicans are not everywhere the same. Variations (sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant) in the 50 political cultures of the states yield considerable differences overall in what it means to be, or to vote, Democratic or Republican. These differences suggest that one may be justified in referring to the American two-party system as masking something more like a hundred-party system."

Political spectrum of the two major parties[]

During the 20th century, the overall political philosophy of both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party underwent a dramatic shift from their earlier philosophies. From the 1860s to the 1950s, the Republican Party was considered to be the more classically liberal of the two major parties and the Democratic Party the more classically conservative/populist of the two.[37][38]

This changed a great deal with the presidency of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal included the founding of Social Security as well as a variety of other federal services and public works projects. Roosevelt's performance in the twin crises of the Depression and World War II led to a sort of polarization in national politics, centered around him; this combined with his increasingly liberal policies to turn FDR's Democrats to the left and the Republican Party further to the right.

During the 1950s and the early 1960s, both parties essentially expressed a more centrist approach to politics on the national level and had their liberal, moderate, and conservative wings influential within both parties.

From the early 1960s, the conservative wing became more dominant in the Republican Party, and the liberal wing became more dominant in the Democratic Party. The 1964 presidential election heralded the rise of the conservative wing among Republicans. The liberal and conservative wings within the Democratic Party were competitive until 1972, when George McGovern's candidacy marked the triumph of the liberal wing. This similarly happened in the Republican Party with the candidacy and later landslide election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, which marked the triumph of the conservative wing.

By the 1980 election, each major party had largely become identified by its dominant political orientation. Strong showings in the 1990s by reformist independent Ross Perot pushed the major parties to put forth more centrist presidential candidates, like Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. Polarization in Congress was said by some[who?] to have been cemented by the Republican takeover of 1994. Others say that this polarization had existed since the late 1980s when the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress.

Liberals within the Republican Party and conservatives within the Democratic Party and the Democratic Leadership Council neoliberals have typically fulfilled the roles of so-called political mavericks, radical centrists, or brokers of compromise between the two major parties. They have also helped their respective parties gain in certain regions that might not ordinarily elect a member of that party; the Republican Party has used this approach with centrist Republicans such as Rudy Giuliani, George Pataki, Richard Riordan and Arnold Schwarzenegger. The 2006 elections sent many centrist or conservative Democrats to state and federal legislatures including several, notably in Kansas and Montana, who switched parties.

Religious groups[]

Religious groups and churches often become political pressure groups and parts of political coalitions, despite the Establishment Clause in the US Constitution. In recent decades, one of the most notable coalitions has been composed of conservative evangelical Protestants and the broader Republican Party.[39] However, some scholars have argued that this coalition may be starting to split, as non-conservative and moderate evangelical Protestants supported then-candidate Barack Obama in 2008.[39] Even if political coalitions between religious groups and political parties split or change, relative to other religions, Christianity has been noted as having a continual dominant impact on politics in the United States.[39] This dominance has translated to pressuring policymakers to pass laws influenced by religious views, such as laws related to morality and personal conduct.[40] A study focusing on this type of political pressure used the alcohol and gambling laws of states as case studies for measuring the impact of religious groups, and it found that large conservative Protestant populations and strong religious pressures had a greater association with more restrictive initial laws than economic development—demonstrating how the presence of religious groups can potentially influence policy.[40]

Concerns about oligarchy[]

Some views suggest that the political structure of the United States is in many respects an oligarchy, where a small economic elite overwhelmingly determines policy and law.[41] Some academic researchers suggest a drift toward oligarchy has been occurring by way of the influence of corporations, wealthy, and other special interest groups, leaving individual citizens with less impact than economic elites and organized interest groups in the political process.[42][43][44][45]

A study by political scientists Martin Gilens (Princeton University) and Benjamin Page (Northwestern University) released in April 2014 suggested that when the preferences of a majority of citizens conflicts with elites, elites tend to prevail.[42] While not characterizing the United States as an "oligarchy" or "plutocracy" outright, Gilens and Page give weight to the idea of a "civil oligarchy" as used by Jeffrey A. Winters, saying, "Winters has posited a comparative theory of 'Oligarchy,' in which the wealthiest citizens – even in a 'civil oligarchy' like the United States – dominate policy concerning crucial issues of wealth- and income-protection." In their study, Gilens and Page reached these conclusions:

When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the US political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it. ... [T]he preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.[46]

E.J. Dionne Jr. described what he considers the effects of ideological and oligarchical interests on the judiciary. The journalist, columnist, and scholar interprets recent Supreme Court decisions as ones that allow wealthy elites to use economic power to influence political outcomes in their favor. In speaking about the Supreme Court's McCutcheon v. FEC and Citizens United v. FEC decisions, Dionne wrote: "Thus has this court conferred on wealthy people the right to give vast sums of money to politicians while undercutting the rights of millions of citizens to cast a ballot."[47]

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman wrote:

The stark reality is that we have a society in which money is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few people. This threatens to make us a democracy in name only.[48]

Concerns about political representation[]

Observations of historical trends and current governmental demographics have raised concerns about the equity of political representation in the United States. In particular, scholars have noted that levels of descriptive representation—which refers to when political representatives share demographic backgrounds or characteristics with their constituents—do not match the racial and gender makeup of the US.[49] Descriptive representation is noted to be beneficial because of its symbolic representative benefits as a source of emotional identification with one's representatives.[28] Furthermore, descriptive representation can lead to more substantive and functional representation, as well as greater institutional power, which can result in minority constituents having both representatives with matching policy views and power in the political system.[49][50] Serving as a congressional committee chair is considered to be a good example of this relationship, as chairs control which issues are addressed by committees, especially through hearings that bring substantial attention to certain issues.[49] Though minorities like African Americans and Latinos have rarely served as committee chairs, studies have shown that their presence has directly led to significantly higher likelihoods of minority issues being addressed.[49] Given that racial and ethnic minorities of all backgrounds have historically been marginalized from participating in the US political system, their political representation and access to policymaking has been limited.[49] Similarly, women lack proportional representation in the United States, bringing into question the extent to which women's issues are adequately addressed.[51] Other minority groups, such as the LGBTQ community, have also been disadvantaged by an absence of equitable representation—especially since scholars have noted their gradual shift from originally being perceived as more of a moral political issue to being considered an actual constituency.[52]

Political representation is also an essential part of making sure that citizens have faith that representatives, political institutions, and democracy take their interests into account.[28] For women and minorities, this issue can occur even in the levels of government that are meant to be closest to constituents, such as among members of Congress in the House of Representatives. Scholars have noted that in positions such as these, even close proximity to constituents does not necessarily translate to an understanding of their needs or experiences and that constituents can still feel unrepresented.[28] In a democracy, a lack of faith in one's representatives can cause them to search for less-democratic alternative forms of representation, like unelected individuals or interest groups.[28] For racial and ethnic minorities, the risk of seeking alternative representation is especially acute, as lived experiences often lead to different political perspectives that can be difficult for white representatives to fully understand or adequately address.[49] Moreover, studies have begun to increasingly show that people of all races and genders tend to prefer having members of Congress who share their race or gender, which can also lead to more engagement between constituents and their representatives, as well as higher likelihoods of contacting or having faith in their congressperson.[28] In addition to making it more likely that constituents will trust their representatives, having descriptive representation can help sustain an individual's positive perceptions of government. When considering women in particular, it has been suggested that broader economic and social equality could result from first working toward ensuring more equitable political representation for women, which would also help promote increased faith between women and their representatives.[53]

Race, ethnicity, and political representation[]

African Americans[]

Although African Americans have begun to continually win more elected positions and increase their overall political representation, they still lack proportional representation across a variety of different levels of government.[29] Some estimates indicate that most gains for African Americans—and other minorities in general—have not occurred at higher levels of government, but rather at sub-levels in federal and state governments.[29] Additionally, congressional data from 2017 revealed that 35.7% of African Americans nationwide had a congressperson of the same race, while the majority of black Americans were represented by members of Congress of a different race.[28] Scholars have partially explained this discrepancy by focusing on the obstacles that black candidates face. Factors like election type, campaign costs, district demographics, and historical barriers, such as voter suppression, can all hinder the likelihood of a black candidate winning an election or even choosing to enter into an election process.[29] Demographics, in particular, are noted to have a large influence on black candidate success, as research has shown that the ratio of white-to-black voters can have a significant impact on a black candidate's chance of winning an election and that large black populations tend to increase the resources available to African American candidates.[29] Despite the variety of obstacles that have contributed to the lack of proportional representation for African Americans, other factors have been found to increase the likelihood of a black candidate winning an election. Based on data from a study in Louisiana, prior black incumbency, as well as running for an office that other black candidates had pursued in the past, increased the likelihood of African Americans entering into races and winning elections.[29]

Hispanic and Latino Americans[]

As the most populous minority demographic identified in the 2010 US Census, Hispanic and Latino Americans have become an increasingly important constituency that is spread throughout the United States.[54] Despite also comprising 15% of the population in at least a quarter of House districts, Latino representation in Congress has not correspondingly increased.[54] Furthermore, in 2017, Latino members of Congress only represented about one-quarter of the total Latino population in the US.[28] While there are many potential explanations for this disparity, including issues related to voter suppression, surveys of Latino voters have identified trends unique to their demographic—though survey data has still indicated that descriptive representation is important to Hispanic and Latino voters.[54] While descriptive representation may be considered important, an analysis of a 2004 national survey of Latinos revealed that political participation and substantive representation were strongly associated with each other, possibly indicating that voters mobilize more on behalf of candidates whose policy views reflect their own, rather than for those who share their ethnic background.[50] Moreover, a breakdown of the rationale for emphasizing descriptive representation reveals additional factors behind supporting Latino candidates, such as the view that they may have a greater respect and appreciation for Spanish or a belief that Latinos are "linked" together, indicating the significance of shared cultural experiences and values.[54] Although the reasons behind choosing to vote for Latino candidates are not monolithic, the election of Latinos to Congress has been identified as resulting in benefits for minorities overall. While it has been argued that unique district-related issues can take equal or greater precedence than Latino interests for Hispanic and Latino members of Congress, studies have also shown that Latinos are more likely to support African American members of Congress—and vice versa—beyond just what is expected from shared party membership.[50]

Native Americans[]

Similar to other minority groups, Native Americans often lack representation due to electoral policies. Gerrymandering, in particular, is noted as a method of concentrating Native voters in a limited number of districts to reduce their ability to influence multiple elections.[27] Despite structural efforts to limit their political representation, some states with large Native American populations have higher levels of representation. South Dakota has a Native population of about 9% with multiple federally recognized tribal nations, and it has been used as a case study of representation.[27] A 2017 study that conducted interviews of former state elected officials in South Dakota revealed that even though many felt that they were only able to implement a limited number of significant changes for tribal communities, they still considered it to be "absolutely essential" that Native Americans had at least some descriptive representation to prevent complete exclusion from the political process.[27] Moreover, formerly elected state and local government officials asserted that ensuring that the issues and concerns of tribal nations were addressed and understood depended on politicians with Native backgrounds.[27] Historically-backed suspicion and skepticism of the predominantly white US government was also considered to be an important reason for having representatives that reflect the histories and views of Native Americans.[27]

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders[]

Relative to other, larger minority demographics in the United States, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) face different challenges related to political representation. Few congressional districts are comprised of a population that includes over 50% Asian Americans, which can elevate the likelihood of being represented by someone of a different race or ethnicity.[28] As with other minorities, this can result in people feeling unrepresented by their member of Congress.[28]

Gender and political representation[]

Women have made continual socioeconomic progress in many key areas of society, such as in employment and education, and in comparison to men, women have voted at higher rates for over forty years—making their lack of more proportional representation in the political system surprising.[51][53] Some scholars have partially attributed this discrepancy to the electoral system in the United States, as it does not provide a mechanism for the types of gender quotas seen in other countries.[53] Additionally, even though gerrymandering and concentrated political representation can essentially ensure at least some representation for minority racial and ethnic groups, women—who are relatively evenly spread throughout the United States—do not receive similar benefits from this practice.[28] Among individuals, however, identifying the source of unequal gender representation can be predicted along party and ideological lines. A survey of attitudes toward women candidates revealed that Democrats are more likely to attribute systemic issues to gender inequalities in political representation, while Republicans are less likely to hold this perspective.[51] While identifying an exact source of inequality may ultimately prove unlikely, some recent studies have suggested that the political ambitions of women may be influenced by the wide variety of proposed factors attributed to the underrepresentation of women.[51] In contrast to attributing specific reasons to unequal representation, political party has also been identified as a way of predicting if a woman running for office is more likely to receive support, as women candidates are more likely to receive votes from members of their party and Independents.[51]

Social inequality and sexism[]

Social inequality and sexism have been noted by scholars as influencing the electoral process for women. In a survey of attitudes toward women candidates, women respondents were far more likely to view the process of running for office as "hostile" to women than men, especially when considering public hesitancy to support women candidates, media coverage, and public discrimination.[51] Political fundraising for candidates is also an area of inequality, as men donate at a higher rate than women—which is compounded by gender and racial inequalities related to income and employment.[53] However, recent increases in women-focused fundraising groups have started to alter this imbalance.[53] Given that disproportionate levels of household labor often become the responsibility of women, discrimination within households has also been identified as a major influence on the capability of women to run for office.[53] For women in the LGBTQ community, some scholars have raised concern about the unequal attention paid to the needs of lesbians compared to transgender, bisexual, and queer women, with lesbian civil rights described as receiving more of a focus from politicians.[52]

Social pressures and influences[]

Social pressures are another influence on women who run for office, often coinciding with sexism and discrimination. Some scholars have argued that views of discrimination have prompted a decrease in the supply of women willing to run for office, though this has been partially countered by those who argue that women are actually just more "strategic" when trying to identify an election with favorable conditions.[53] Other factors, like the overrepresentation of men, have been described as influencing perceptions of men as somehow inherently more effective as politicians or leaders, which some scholars argue could pressure women to stay out of elections.[53] However, others contend that the overrepresentation of men can actually result in "political momentum" for women, such as during the Year of the Woman.[53] Within some racial and ethnic groups, social influences can also shape political engagement. Among Latinos, Latinas are more likely to partake in nonelectoral activities, like community organizing, when compared to men.[54] Despite differences in political activity and social pressures, elected women from both political parties have voiced their support for electing more women to Congress to increase the acceptance of their voices and experiences.[53] Furthermore, studies have found that increasing the descriptive representation of women can provide positive social influences for democracy as a whole, such as improved perceptions of an individual's political efficacy and government's responsiveness to the needs of people.[28] When women can vote for a woman candidate of the same party, studies have also found that these influences can be magnified.[28]

LGBT political representation[]

Although some scholars have disputed the benefits of descriptive representation, only a small number have argued that this form of representation actually has negative impacts on the group it represents.[55] Studies of bills relating to LGBT rights in state legislatures have provided a more nuanced analysis. Pro-LGBT bills tend to be introduced in higher numbers when more LGBT representatives are elected to state legislatures, which may also indicate an increased likelihood of substantive representation.[55] Increases in openly LGBT state lawmakers have also been hypothesized to inadvertently result in more anti-LGBT legislation, potentially as the result of backlash to their presence.[55] Despite the risk of negative consequences, at least one study has concluded that the LGBT community receives net-benefits from increased openly LGBT representation.[55] On the federal level, the presence of the Congressional LGBTQ+ Equality Caucus has been identified as improving the ability of Congress to address the intersectional issues faced by the LGBT community, as well as provide a source of pressure other than constituency on members of Congress to address LGBT issues.[52] Additionally, non-LGBT members of the caucus have been criticized for not sponsoring enough legislation, emphasizing the value of openly LGBT members of Congress.[52] While descriptive representation has provided benefits overall, scholars have noted that some groups in the community, such as transgender and bisexual people, tend to receive less focus than gays and lesbians.[52]

Reform[]

See also[]

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Gun politics in the United States

- Political ideologies in the United States

- Politics of the Southern United States

- Initiatives and referendums in the United States

References[]

- ^ Statistical Abstract: 2010 p. 416.

- ^ Ann O'M. Bowman and Richard C. Kearney, State and Local Government: The Essentials (2008) p. 78

- ^ http://www.talgov.com/commission

- ^ Wolf, Zachary B. (3 November 2020). "The Electoral College, explained". CNN. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Paradise". Paradise. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c EDICK, COLE (2015). "Relics of Colonialism: Overseas Territories Across the Globe". Harvard International Review. 37 (1): 11–12. ISSN 0739-1854. JSTOR 43746158.

- ^ "American Samoa". www.doi.gov. 2015-06-11. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ Guthunz, Ute (1997). "Beyond Decolonization and Beyond Statehood? Puerto Rico's Political Development in Association with the United States". Iberoamericana (1977-2000). 21 (3/4 (67/68)): 42–55. ISSN 0342-1864. JSTOR 41671654.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kömives, Lisa M. (2004). "Enfranchising a Discrete and Insular Minority: Extending Federal Voting Rights to American Citizens Living in United States Territories". The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. 36 (1): 115–138. ISSN 0884-1756. JSTOR 40176588.

- ^ http://www.fec.gov/pages/brochures/pubfund.shtml

- ^ http://www.lasvegassun.com/news/2009/sep/28/recession-means-theres-less-money-campaigns/

- ^ http://www.america.gov/st/usg-english/2008/July/20080710130812mlenuhret0.6269953.html

- ^ Patricia U. Bonomi, A Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York (Columbia U.P., 1971) p 281

- ^ Beeman, Richard R. (2005). "The Varieties of Deference in Eighteenth-Century America". Early American Studies. 3 (2): 311–340. doi:10.1353/eam.2007.0024. S2CID 144931559.

- ^ Patricia U. Bonomi, A Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York (Columbia U.P., 1971) pp 281-2

- ^ Anton-Hermann, The Rise of the legal profession in America (2 vol 1965), vol 1.

- ^ Bonomi, A Factious People, pp 281-286

- ^ Weeks, J. (2007). Inequality Trends in Some Developed OECD Countries. In J. K. S. & J. Baudot (Eds.) Flat world, big gaps: Economic liberalization, globalization, poverty & inequality (159-176). New York: Zed Books.

- ^ Thomas, E. (March 10, 2008). "He knew he was right". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Clark, B. (1998). Political economy: A comparative approach. Westport, CT: Preager.

- ^ Alber, Jens (1988). "Is there a crisis of the welfare state? Crossnational evidence from Europe, North America, and Japan". European Sociological Review. 4 (3): 181–205. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036484.

- ^ Barr, N. (2004). Economics of the welfare state. New York: Oxford University Press (USA).

- ^ "Economist Intelligence Unit. (July 11, 2007). United States: Political Forces". The Economist. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ Ballad-Rosa (2021). "Economic Decline, Social Identity, and Authoritarian Values in the United States". International Studies Quarterly. doi:10.1093/ISQ/SQAB027. S2CID 221317686.

- ^ Washington's Farewell Address

- ^ "March 2021 Ballot Access News Print Edition".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Schroedel, Jean Reith; Aslanian, Artour (2017). "A Case Study of Descriptive Representation: The Experience of Native American Elected Officials in South Dakota". American Indian Quarterly. 41 (3): 250–286. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.41.3.0250. ISSN 0095-182X. JSTOR 10.5250/amerindiquar.41.3.0250. S2CID 159930747.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n English, Ashley; Pearson, Kathryn; Strolovitch, Dara Z. (2019). "Who Represents Me? Race, Gender, Partisan Congruence, and Representational Alternatives in a Polarized America". Political Research Quarterly. 72 (4): 785–804. doi:10.1177/1065912918806048. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45223003. S2CID 158576286.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Shah, Paru (2014). "It Takes a Black Candidate: A Supply-Side Theory of Minority Representation". Political Research Quarterly. 67 (2): 266–279. doi:10.1177/1065912913498827. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 24371782. S2CID 155069482.

- ^ Baker, Peter; VandeHei, Jim (2006-11-08). "A Voter Rebuke For Bush, the War And the Right". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

Bush and senior adviser Karl Rove tried to replicate that strategy this fall, hoping to keep the election from becoming a referendum on the president's leadership.

- ^ "Election '98 Lewinsky factor never materialized". CNN. 1998-11-04.

Americans shunned the opportunity to turn Tuesday's midterm elections into a referendum on President Bill Clinton's behavior, dashing Republican hopes of gaining seats in the House and Senate.

- ^ Davis, William L., and Bob Figgins. 2009. Do Economists Believe American Democracy Is Working? Econ Journal Watch 6(2): 195-202. Econjwatch.org

- ^ http://www.shmoop.com/political-parties/founding-fathers-political-parties.html

- ^ [citation needed]

- ^ Richard Hofstadter, The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780-1840 (1970).

- ^ Shigeo Hirano and James M. Snyder Jr. "The decline of third-party voting in the United States." The Journal of Politics 69.1 (2007): 1-16.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, The Republicans: A History of the Grand Old Party (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- ^ Jules Witcover, Party of the People: A History of the Democrats (2003)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c BERNSTEIN, ELIZABETH; JAKOBSEN, JANET R (2010). "Sex, Secularism and Religious Influence in US Politics". Third World Quarterly. 31 (6): 1023–1039. doi:10.1080/01436597.2010.502739. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 27896595. PMID 20857575. S2CID 39112453.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fairbanks, David (1977). "Religious Forces and "Morality" Policies in the American States". The Western Political Quarterly. 30 (3): 411–417. doi:10.2307/447941. ISSN 0043-4078. JSTOR 447941.

- ^ Sevcik, J.C. (April 16, 2014) "The US is not a democracy but an oligarchy, study concludes" UPI

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martin Gilens & Benjamin I. Page (2014). "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens" (PDF). Perspectives on Politics. 12 (3): 564–581. doi:10.1017/S1537592714001595.

- ^ Piketty, Thomas (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press. ISBN 067443000X p. 514: *"the risk of a drift towards oligarchy is real and gives little reason for optimism about where the United States is headed."

- ^ (French economist Thomas Piketty), Associated Press, December 23, 2017, Q&A: A French economist's grim view of wealth gap, Accessed April 26, 2014, "...The main problem to me is really the proper working of our democratic institutions. It's just not compatible with an extreme sort of oligarchy where 90 percent of the wealth belongs to a very tiny group ..."

- ^ Alan Wolfe (book reviewer), October 24, 2010, The Washington Post, Review of "The Mendacity of Hope," by Roger D. Hodge, Accessed April 26, 2014, "...Although Hodge devotes a chapter to foreign policy, the main charge he levels against Obama is that, like all politicians in the United States, he serves at the pleasure of a financial oligarchy. ... "

- ^ Gilens, Martin; Page, Benjamin I. (2014). "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens". Perspectives on Politics. 12 (3): 564–581. doi:10.1017/S1537592714001595.

When the preferences of economic elites and the stands of organized interest groups are controlled for, the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy."

- ^ E.J. Dionne Jr., April 6, 2014, Washington Post, Supreme oligarchy, Accessed April 26, 2014, "...Thus has this court conferred on wealthy people the right to give vast sums of money to politicians while undercutting the rights of millions of citizens to cast a ballot. ... "

- ^ Paul Krugman, The New York Times, November 3, 2011, Oligarchy, American Style, Accessed April 26, 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Ellis, William Curtis; Wilson, Walter Clark (2013). "Minority Chairs and Congressional Attention to Minority Issues: The Effect of Descriptive Representation in Positions of Institutional Power". Social Science Quarterly. 94 (5): 1207–1221. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12023. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 42864138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jeong, Hoi Ok (2013). "Minority Policies and Political Participation Among Latinos: Exploring Latinos' Response to Substantive Representation". Social Science Quarterly. 94 (5): 1245–1260. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00883.x. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 42864140.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Dolan, Kathleen; Hansen, Michael (2018). "Blaming Women or Blaming the System? Public Perceptions of Women's Underrepresentation in Elected Office". Political Research Quarterly. 71 (3): 668–680. doi:10.1177/1065912918755972. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45106690. S2CID 149220469.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e LGBTQ Politics: A Critical Reader. NYU Press. 2017. ISBN 978-1-4798-9387-4. JSTOR j.ctt1pwt8jh.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. JSTOR 48563031. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Wallace, Sophia J. (2014). "Examining Latino Support for Descriptive Representation: The Role of Identity and Discrimination". Social Science Quarterly. 95 (2): 311–327. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12038. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 26612166.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Haider-Markel, Donald P. (2007). "Representation and Backlash: The Positive and Negative Influence of Descriptive Representation". Legislative Studies Quarterly. 32 (1): 107–133. doi:10.3162/036298007X202001. ISSN 0362-9805. JSTOR 40263412.

Further reading[]

- Barone, Michael et al. The Almanac of American Politics, 2020 (2019) 1000+ pages covers every member of Congress and governor in depth; new edition every two years since 1975.

- Brewer, Mark D. and L. Sandy Maisel. Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process (9th ed. 2020) excerpt

- Edwards, George C. Martin P. Wattenberg, and Robert L. Lineberry. Government in America: People, Politics, and Policy (16th Edition, 2013)

- Finkelman, Paul, and Peter Wallenstein, eds. The Encyclopedia Of American Political History (2001), short essays by scholars

- Greene, Jack P., ed. Encyclopedia of American Political History: Studies of the Principal Movements and Ideas (3 vol. 1984), long essays by scholars

- Hershey, Marjorie R. Party Politics in America (14th Edition, 2010)

- Hetherington, Marc J., and Bruce A. Larson. Parties, Politics, and Public Policy in America (11th edition, 2009), 301 pp

- Kazin, Michael, Rebecca Edwards, and Adam Rothman, eds. The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History (2 vol 2009)

- Maisel, L. Sandy, ed. Political Parties and Elections in the United States: an Encyclopedia 2 vol (Garland, 1991). (ISBN 0-8240-7975-2), short essays by scholars

- Maisel, L. Sandy. American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction (2007), 144 pp

- O'Connor, Karen, Larry J. Sabato, and Alixandra B. Yanus. American Government: American Government: Roots and Reform (11th ed. 2011)

- Wilson, James Q., et al. American Government: Institutions and Policies (16th ed. 2018) excerpt

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Politics of the United States. |

| Scholia has a topic profile for Politics of the United States. |

- Official party websites

- Politics of the United States