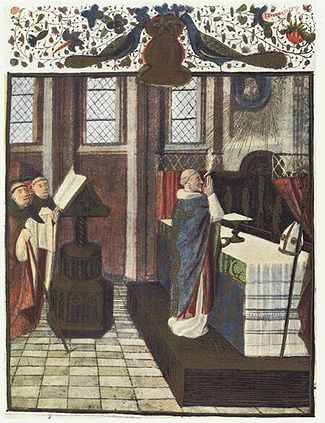

Pre-Tridentine Mass

Pre-Tridentine Mass refers to the variants of the liturgical rite of Mass in Rome before 1570, when, with his bull Quo primum, Pope Pius V made the Roman Missal, as revised by him, obligatory throughout the Latin-Rite or Western Church, except for those places and congregations whose distinct rites could demonstrate an antiquity of two hundred years or more.[1]

The pope made this revision of the Roman Missal, which included the introduction of the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar and the addition of all that in his Missal follows the Ite missa est, at the request of Council of Trent (1545–63), presented to his predecessor at its final session.[2]

Outside Rome before 1570, many other liturgical rites were in use, not only in the East, but also in the West. Some Western rites, such as the Mozarabic Rite, were unrelated to the Roman Rite which Pope Pius V revised and ordered to be adopted generally, and even areas that had accepted the Roman rite had introduced changes and additions. As a result, every ecclesiastical province and almost every diocese had its local use, such as the Use of Sarum, the Use of York and the Use of Hereford in England. In France there were strong traces of the Gallican Rite. With the exception of the relatively few places where no form of the Roman Rite had ever been adopted, the Canon of the Mass remained generally uniform, but the prayers in the "Ordo Missae", and still more the "Proprium Sanctorum" and the "Proprium de Tempore", varied widely.[3]

The Pre-Tridentine Mass survived post-Trent in some Anglican and Lutheran areas with some local modification from the basic Roman rite until the time when worship switched to the vernacular. Dates of switching to the vernacular, in whole or in part, varied widely by location. In some Lutheran areas this took three hundred years, as choral liturgies were sung by schoolchildren who were learning Latin.[4]

Earliest accounts[]

The earliest surviving account of the celebration of the Eucharist or the Mass in Rome is that of Saint Justin Martyr (died c. 165), in chapter 67 of his First Apology:[5]

On the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons.

In chapter 65, Justin Martyr says that the kiss of peace was given before the bread and the wine mixed with water were brought to "the president of the brethren". The initial liturgical language used was Greek, before approximately the year 190 under Pope Victor, when the Church in Rome changed from Greek to Latin, except in particular for the Hebrew word "Amen", whose meaning Justin explains in Greek (γένοιτο), saying that by it "all the people present express their assent" when the president of the brethren "has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings".[6]

Also, in Chapter 66 of Justin Martyr's First Apology, he describes the change (explained by Roman Catholic theologians as evidence for transubstantiation) which occurs on the altar: "For not as common bread nor common drink do we receive these; but since Jesus Christ our Saviour was made incarnate by the word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so too, as we have been taught, the food which has been made into the Eucharist by the Eucharistic prayer set down by him, and by the change of which our blood and flesh is nurtured, is both the flesh and the blood of that incarnated Jesus". (First Apology 66:1–20 [AD 148]).

The descriptions of the Mass liturgy in Rome by Hippolytus (died c. 235) and Novatian (died c. 250) are similar to Justin's.

Early changes[]

It is unclear when the language of the celebration changed from Greek to Latin. Pope Victor I (190–202), may have been the first to use Latin in the liturgy in Rome. Others think Latin was finally adopted nearly a century later.[7] The change was probably gradual, with both languages being used for a while.[8]

Before the pontificate of Pope Gregory I (590–604), the Roman Mass rite underwent many changes, including a "complete recasting of the Canon" (a term that in this context means the Anaphora or Eucharistic Prayer),[9] the number of Scripture readings was reduced, the prayers of the faithful were omitted (leaving, however, the "Oremus" that once introduced them), the kiss of peace was moved to after the Consecration, and there was a growing tendency to vary, in reference to the feast or season, the prayers, the Preface, and even the Canon.

With regard to the Roman Canon of the Mass, the prayers beginning Te igitur, Memento Domine and Quam oblationem were already in use, even if not with quite the same wording as now, by the year 400; the Communicantes, the Hanc igitur, and the post-consecration Memento etiam and Nobis quoque were added in the fifth century.[10][11]

Pope Gregory I made a general revision of the liturgy of the Mass, "removing many things, changing a few, adding some," as his biographer, John the Deacon, writes. He is credited with adding the words 'diesque nostros in tua pace disponas' to the Hanc igitur, and he placed the Lord's Prayer immediately after the Canon.

Middle Ages[]

Towards the end of the eighth century Charlemagne ordered the Roman rite of Mass to be used throughout his domains. However, some elements of the preceding Gallican rites were fused with it north of the Alps, and the resulting mixed rite was introduced into Rome under the influence of the emperors who succeeded Charlemagne. Gallican influence is responsible for the introduction into the Roman rite of dramatic and symbolic ceremonies such as the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, and much of the Holy Week ritual.[12]

The recitation of the Credo (Nicene Creed) after the Gospel is attributed to the influence of Emperor Henry II (1002–24). Gallican influence explains the practice of incensing persons, introduced in the eleventh or twelfth century; "before that time incense was burned only during processions (the entrance and Gospel procession)."[13] Private prayers for the priest to say before Communion were another novelty. About the thirteenth century, an elaborate ritual and additional prayers of French origin were added to the Offertory, at which the only prayer that the priest in earlier times said was the Secret; these prayers varied considerably until fixed by Pope Pius V in 1570. Pope Pius V also introduced the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar, previously said mostly in the sacristy or during the procession to the altar as part of the priest's preparation, and also for the first time formally admitted into the Mass all that follows the Ite missa est in his edition of the Roman Missal. Later editions of the Roman Missal abbreviated this part by omitting the Canticle of the Three Young Men and Psalm 150, followed by other prayers, that in Pius V's edition the priest was to say while leaving the altar.[14]

From 1474 until Pope Pius V's 1570 text, there were at least 14 different printings that purported to present the text of the Mass as celebrated in Rome, rather than elsewhere, and which therefore were published under the title of "Roman Missal". These were produced in Milan, Venice, Paris and Lyon. Even these show variations. Local Missals, such as the Parisian Missal, of which at least 16 printed editions appeared between 1481 and 1738, showed more important differences.[15]

The Roman Missal that Pope Pius V issued at the request of the Council of Trent, gradually established uniformity within the Western Church after a period that had witnessed regional variations in the choice of Epistles, Gospels, and prayers at the Offertory, the Communion, and the beginning and end of Mass. With the exception of a few dioceses and religious orders, the use of this Missal was made obligatory, giving rise to the 400-year period when the Roman-Rite Mass took the form now known as the Tridentine Mass.

Comparison of the Mass, c. 400 and 1000 AD[]

| c. 400 | c. 1000 |

|---|---|

| Mass of the Catechumens | Fore-Mass |

| Introductory greeting | Entrance ceremonies

|

Lesson 1: the Prophets Responsorial psalm Lesson 2: Epistle Responsorial psalm Lesson 3: Gospel |

Service of readings |

| Sermon | Sermon (optional) |

| Prayer Dismissal of the catechumens |

Credo "Oremus" |

| Communion of the Faithful | Sacrifice-Mass |

| Offering of gifts Prayer over the offerings |

Offertory rites |

| Eucharistic prayers |

Eucharistic prayers |

| Communion rites Psalm accompanying communion Prayer |

Communion cycle

|

| Dismissal of the faithful | Ite, missa est or Benedicamus Domino |

Source: Hoppin, Richard (1977), Medieval Music, New York: Norton, pp. 119, 122.

See also[]

- Roman Catholic Church

- Eucharist

- The Mass

- Tridentine Mass

- Mass of Paul VI

- Roman Missal

- Sarum rite

- Missale Aboense

- Use of York

- Stowe Missal

- Durham Rite

References[]

- ^ Ghislieri, Antonio Michele (14 July 1570), Quo primum (bull), Papal encyclicals,

We decided to entrust this work to learned men of our selection. They very carefully collated all their work with the ancient codices in Our Vatican Library and with reliable, preserved or emended codices from elsewhere. Besides this, these men consulted the works of ancient and approved authors concerning the same sacred rites; and thus they have restored the Missal itself to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers. When this work has been gone over numerous times and further emended, after serious study and reflection, We commanded that the finished product be printed and published

. - ^ "Trent". American Catholic Truth Society..

- ^ Thurston, Herbert (1913). "Missal". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Tables of years of switch to the vernacular

- ^ "Fathers". New Advent..

- ^ Spencer, The Rev. Sidney (2013-03-05), "Christianity", Britannica (encyclopaedia) (online ed.), retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ^ Mohrmann, Christine (1961–77), Études sur le latin des chrétiens [Studies on the Latin of the Christian], vol. I, Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, p. 54,

The complete and definitive Latinization of the Roman liturgy seems to have happened toward the middle of the fourth century

- ^ Plummer, Alfred (1985), Boudens, Robrecht (ed.), Conversations with Dr. Döllinger 1870–1890, Leuven University Press, p. 13,

The first Christians in Rome were chiefly people who came from the East and spoke Greek. The founding of Constantinople naturally drew such people thither rather than to Rome, and then Christianity at Rome began to spread among the Roman population, so that at last the bulk of the Christian population in Rome spoke Latin. Hence the change in the language of the liturgy. [...] The liturgy was said (in Latin) first in one church and then in more, until the Greek liturgy was driven out, and the clergy ceased to know Greek. About 415 or 420 we find a Pope saying that he is unable to answer a letter from some Eastern bishops, because he has no one who could write Greek

. - ^ "Liturgy of the Mass", Catholic Encyclopedia, New advent,

...the Eucharistic prayer was fundamentally changed and recast

. - ^ Jungmann, Josef Andreas, SJ (1949), Missarum Sollemnia - Eine genetische Erklärung der römischen Messe [Solemn mass — A genetic explanation of the Roman Mass] (in German), vol. I, Vienna: Herder, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Schmidt, Hermannus AP (1960), Introductio in Liturgiam Occidentalem [Introduction to Western liturgy] (in Latin), Rome-Freiburg-Barcelona: Herder, p. 352

- ^ "The Franks Adopt the Roman Rite". Liturgica. Archived from the original on 2013-10-24. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ Fathers, New Advent

- ^ Sodi & Triacca 1998, pp. 291–92.

- ^ Sodi & Triacca 1998, pp. XV–XVI.

Bibliography[]

- Sodi, Manlio; Triacca, Achille Maria, eds. (1998). Missale Romanum [Roman missal] (in Latin) (Princeps ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 88-209-2547-8.

External links[]

- Atchley, E. G. (1905), Ordo Romanus Primus, Archive.

- Latin liturgical rites